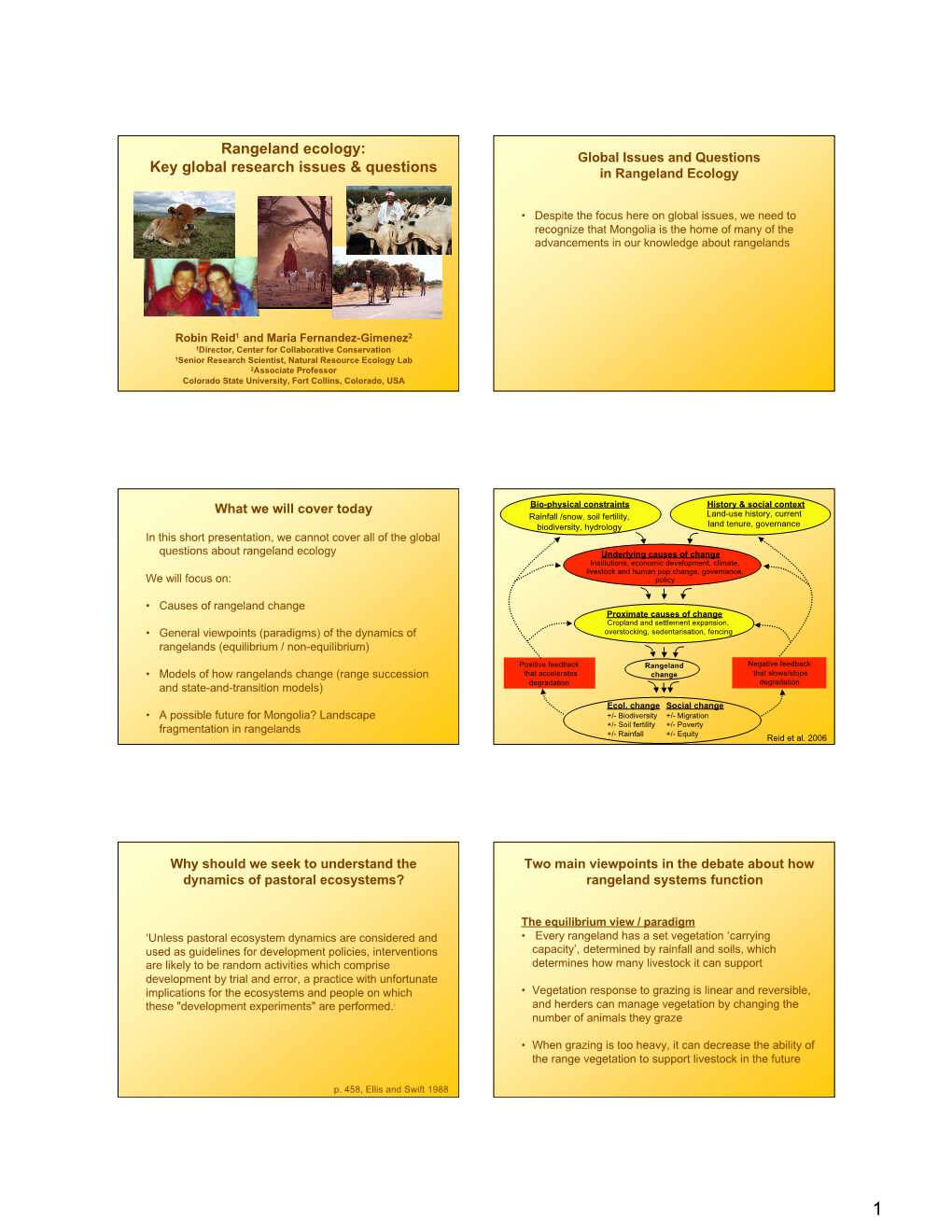

Rangeland Ecology: Key Global Research Issues & Questions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impacts of Technology on U.S. Cropland and Rangeland Productivity Advisory Panel

l-'" of nc/:\!IOIOO _.. _ ... u"' "'"'" ... _ -'-- Impacts of Technology on U.S. Cropland w, in'... ' .....7 and Rangeland Productivity August 1982 NTIS order #PB83-125013 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 82-600596 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402 Foreword This Nation’s impressive agricultural success is the product of many factors: abundant resources of land and water, a favorable climate, and a history of resource- ful farmers and technological innovation, We meet not only our own needs but supply a substantial portion of the agricultural products used elsewhere in the world. As demand increases, so must agricultural productivity, Part of the necessary growth may come from farming additional acreage. But most of the increase will depend on intensifying production with improved agricultural technologies. The question is, however, whether farmland and rangeland resources can sustain such inten- sive use. Land is a renewable resource, though one that is highly susceptible to degrada- tion by erosion, salinization, compaction, ground water depletion, and other proc- esses. When such processes are not adequately managed, land productivity can be mined like a nonrenewable resource. But this need not occur. For most agricul- tural land, various conservation options are available, Traditionally, however, farm- ers and ranchers have viewed many of the conservation technologies as uneconom- ical. Must conservation and production always be opposed, or can technology be used to help meet both goals? This report describes the major processes degrading land productivity, assesses whether productivity is sustainable using current agricultural technologies, reviews a range of new technologies with potentials to maintain productivity and profitability simultaneously, and presents a series of options for congressional consideration. -

Rangeland Resources Management Muhammad Ismail, Rohullah Yaqini, Yan Zhaoli, Andrew Billingsley

Managing Natural Resources Rangeland Resources Management Muhammad Ismail, Rohullah Yaqini, Yan Zhaoli, Andrew Billingsley Rangelands are areas which, by reason of physical limitations, low and erratic precipitation, rough topography, poor drainage, or extreme temperature, are less suitable for cultivation but are sources of food for free ranging wild and domestic animals, and of water, wood, and mineral products. Rangelands are generally managed as natural ecosystems that make them distinct from pastures for commercial livestock husbandry with irrigation and fertilisation facilities. Rangeland management is the science and art of optimising returns or benefits from rangelands through the manipulation of rangeland ecosystems. There has been increasing recognition worldwide of rangeland functions and various ecosystem services they provide in recent decades. However, livestock farming is still one of the most important uses of rangelands and will remain so in the foreseeable future. Rangeland Resources and Use Patterns in Afghanistan Afghanistan’s rangelands are specified as land where the predominant vegetation consists of grasses, herbs, shrubs, and may include areas with low-growing trees such as juniper, pistachio, and oak. The term ‘rangeland resources’ refers to biological resources within a specific rangeland and associated ecosystems, including vegetation, wildlife, open forests (canopy coverage less than 30%), non- biological products such as soil and minerals. Today, rangelands comprise between 60-75% of Afghanistan’s total territory, depending on the source of information. Rangelands are crucial in supplying Afghanistan with livestock products, fuel, building materials, medicinal plants, and providing habitat for wildlife. The water resources captured and regulated in Afghan rangelands are the lifeblood of the country and nourishes nearly 4 million ha of irrigated lands. -

Climate Change and Rangelands: Responding Rationally to Uncertainty by Joel R

Climate Change and Rangelands: Responding Rationally to Uncertainty By Joel R. Brown and Jim Thorpe ccording to most estimates, rangeland ecosys- have a dominant infl uence on productivity, stability, and tems occupy about 50% of the earth’s terrestrial profi tability. surface. By itself, this estimate implies range- The interaction between scientists and managers is lands are important to humans, but their impor- critical to understanding and managing the relationships Atance extends far beyond their global dominance. Globally, critical to healthy rangeland ecosystems. While scientists rangelands provide about 70% of the forage for domestic uncover new relationships governing ecosystem behavior, livestock. For many societies, livestock are critical to sur- managers are ultimately responsible for implementing prac- vival. Rangelands also provide a host of ecosystem services tices to ensure continued heath of the systems they manage. technology or other land types cannot provide. Among the One of the most important scientifi c contributions of the most important of these services is climate regulation, or past decade is an enhanced understanding of earth’s climate the ability to sequester and store greenhouse gases such as system and human impacts on climate. Through a collab- carbon dioxide. orative effort, scientists have communicated the links The ability of any rangeland to provide any ecosystem between humans and climate. Policy makers and the public service is dependent, primarily, upon the rangeland’s condi- are generally aware that humans have an infl uence on tion. Degraded rangelands are poor providers of ecosystem climate—an infl uence that is likely to increase in the services, regardless of the commodity. -

Rangeland Management

RANGELANDS 17(4), August 1995 127 Changing SocialValues and Images of Public Rangeland Management J.J. Kennedy, B.L. Fox, and T.D. Osen Many political, economiç-and'ocial changes of the last things (biocentric values). These human values are 30 years have affected Ar'ierican views of good public expressed in various ways—such as laws, rangeland use, rangeland and how it should be managed. Underlying all socio-political action, popularity of TV nature programs, this socio-political change s the shift in public land values governmental budgets, coyote jewelry, or environmental of an American industrial na4i hat emerged from WWII to messages on T-shirts. become an urban, postindutr society in the 1970s. Much of the American public hold environmentally-orientedpublic land values today, versus the commodity and community The Origin of Rangeland Social Values economic development orientation of the earlier conserva- We that there are no and tion era (1900—1969). The American public is also mentally propose fixed, unchanging intrinsic or nature values. All nature and visually tied to a wider world through expanded com- rangeland values are human creations—eventhe biocentric belief that nature has munication technology. value independent of our human endorsement or use. Consider golden eagles or vultures as an example. To Managing Rangelands as Evolving Social Value begin with, recognizing a golden eagle or vulture high in flight is learned behavior. It is a socially taught skill (and not Figure 1 presents a simple rangeland value model of four easily mastered)of distinguishingthe cant of wings in soar- interrelated systems: (1) the environmental/natural ing position and pattern of tail or wing feathers. -

Standards for Rangeland Health and Guidelines

Standards for Rangeland Health and Guidelines for Livestock Grazing Management for Public Lands Administered by the Bureau of Land Management for Montana and the Dakotas Note: These standards and guidelines apply to the Butte, Dillon, and Missoula Field Offices Preamble The Butte Resource Advisory Council (BRAC) has developed standards for rangeland health and guidelines for livestock grazing management for use on the Butte District of the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). The purpose of the S&Gs are to facilitate the achievement and maintenance of healthy, properly functioning ecosystems within the historic and natural range of variability for long-term sustainable use. BRAC determined that the following considerations were very important in the adoption of these S&Gs: 1. For implementation, the BLM should emphasize a watershed approach that incorporates both upland and riparian standards and guidelines. 2. The standards are applicable to rangeland health, regardless of use. 3. The social and cultural heritage of the region and the viability of the local economy, are part of the ecosystem. 4. Wildlife is integral to the proper function of rangeland ecosystems. Standards Standards are statements of physical and biological condition or degree of function required for healthy sustainable rangelands. Achieving or making significant progress towards these functions and conditions is required of all uses of public rangelands as stated in 43 CFR 4180.1. Baseline, monitoring and trend data, when available, should be utilized to assess compliance with standards. Butte STANDARD #1: Uplands are in proper functioning condition. • As addressed by the preamble to these standards and as indicated by: Physical Environment - erosional flow patterns; - surface litter; - soil movement by water and wind; - soil crusting and surface sealing; - compaction layer; - rills; - gullies; - cover amount; and - cover distribution. -

Emerging Issues in Rangeland Ecohydrology: Vegetation Change and the Water Cycle

Emerging Issues in Rangeland Ecohydrology: Vegetation Change and the Water Cycle Item Type text; Article Authors Wilcox, Bradford P.; Thurow, Thomas L. Citation Wilcox, B. P., & Thurow, T. L. (2006). Emerging issues in rangeland ecohydrology: vegetation change and the water cycle. Rangeland Ecology & Management, 59(2), 220-224. DOI 10.2111/05-090R1.1 Publisher Society for Range Management Journal Rangeland Ecology & Management Rights Copyright © Society for Range Management. Download date 01/10/2021 09:03:40 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Version Final published version Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/643426 Rangeland Ecol Manage 59:220–224 | March 2006 Forum: Viewpoint Emerging Issues in Rangeland Ecohydrology: Vegetation Change and the Water Cycle Bradford P. Wilcox1 and Thomas L. Thurow2 Authors are 1Professor, Rangeland Ecology and Management Department, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843-2126; and 2Professor, Renewable Resources Department, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY 82071-3354. Abstract Rangelands have undergone—and continue to undergo—rapid change in response to changing land use and climate. A research priority in the emerging science of ecohydrology is an improved understanding of the implications of vegetation change for the water cycle. This paper describes some of the interactions between vegetation and water on rangelands and poses 3 questions that represent high-priority, emerging issues: 1) How do changes in woody plants affect water yield? 2) What are the ecohydrological consequences of invasion by exotic plants? 3) What ecohydrological feedbacks play a role in rangeland degradation processes? To effectively address these questions, we must expand our knowledge of hydrological connectivity and how it changes with scale, accurately identify ‘‘hydrologically sensitive’’ areas on the landscape, carry out detailed studies to learn where plants are accessing water, and investigate feedback loops between vegetation and the water cycle. -

Biological Soil Crust Rehabilitation in Theory and Practice: an Underexploited Opportunity Matthew A

REVIEW Biological Soil Crust Rehabilitation in Theory and Practice: An Underexploited Opportunity Matthew A. Bowker1,2 Abstract techniques; and (3) monitoring. Statistical predictive Biological soil crusts (BSCs) are ubiquitous lichen–bryo- modeling is a useful method for estimating the potential phyte microbial communities, which are critical structural BSC condition of a rehabilitation site. Various rehabilita- and functional components of many ecosystems. How- tion techniques attempt to correct, in decreasing order of ever, BSCs are rarely addressed in the restoration litera- difficulty, active soil erosion (e.g., stabilization techni- ture. The purposes of this review were to examine the ques), resource deficiencies (e.g., moisture and nutrient ecological roles BSCs play in succession models, the augmentation), or BSC propagule scarcity (e.g., inoc- backbone of restoration theory, and to discuss the prac- ulation). Success will probably be contingent on prior tical aspects of rehabilitating BSCs to disturbed eco- evaluation of site conditions and accurate identification systems. Most evidence indicates that BSCs facilitate of constraints to BSC reestablishment. Rehabilitation of succession to later seres, suggesting that assisted recovery BSCs is attainable and may be required in the recovery of of BSCs could speed up succession. Because BSCs are some ecosystems. The strong influence that BSCs exert ecosystem engineers in high abiotic stress systems, loss of on ecosystems is an underexploited opportunity for re- BSCs may be synonymous with crossing degradation storationists to return disturbed ecosystems to a desirable thresholds. However, assisted recovery of BSCs may trajectory. allow a transition from a degraded steady state to a more desired alternative steady state. In practice, BSC rehabili- Key words: aridlands, cryptobiotic soil crusts, cryptogams, tation has three major components: (1) establishment of degradation thresholds, state-and-transition models, goals; (2) selection and implementation of rehabilitation succession. -

Rangeland Soil Quality—Introduction

Rangeland Sheet 1 Soil Quality Information Sheet Rangeland Soil Quality—Introduction USDA, Natural Resources Conservation Service May 2001 What is rangeland? reflected in soil properties that change in response to management or climate. Rangeland is land on which the native vegetation is predominantly grasses, grasslike plants, forbs, or shrubs. This What does soil quality affect on land includes natural grasslands, savannas, shrub lands, most deserts, tundras, areas of alpine communities, coastal marshes, rangeland? and wet meadows. • Plant production, reproduction, and mortality • Erosion • Water yields and water quality • Wildlife habitat • Carbon sequestration • Vegetation changes • Establishment and growth of invasive plants • Rangeland health How are soil quality and rangeland health related? Rangeland health and soil quality are interdependent. Rangeland health is characterized by the functioning of both the soil and the plant communities. The capacity of the soil to function affects ecological processes, including the capture, What is rangeland health? storage, and redistribution of water; the growth of plants; and the cycling of plant nutrients. For example, increased physical Rangeland health is the degree to which the integrity of the crusting decreases the infiltration capacity of the soil and thus soil, the vegetation, the water, and the air as well as the the amount of water available to plants. As the availability of ecological processes of the rangeland ecosystem are balanced water decreases, plant production declines, some plant species and sustained. may disappear, and the less desirable species may increase in abundance. Changes in vegetation may precede or follow What is soil? changes in soil properties and processes. Significant shifts in vegetation generally are associated with changes in soil Soil is a dynamic resource that supports plants. -

Glossary and Acronyms Glossary Glossary

Glossary andChapter Acronyms 1 ©Kevin Fleming ©Kevin Horseshoe crab eggs Glossary and Acronyms Glossary Glossary 40% Migratory Bird “If a refuge, or portion thereof, has been designated, acquired, reserved, or set Hunting Rule: apart as an inviolate sanctuary, we may only allow hunting of migratory game birds on no more than 40 percent of that refuge, or portion, at any one time unless we find that taking of any such species in more than 40 percent of such area would be beneficial to the species (16 U.S.C. 668dd(d)(1)(A), National Wildlife Refuge System Administration Act; 16 U.S.C. 703-712, Migratory Bird Treaty Act; and 16 U.S.C. 715a-715r, Migratory Bird Conservation Act). Abiotic: Not biotic; often referring to the nonliving components of the ecosystem such as water, rocks, and mineral soil. Access: Reasonable availability of and opportunity to participate in quality wildlife- dependent recreation. Accessibility: The state or quality of being easily approached or entered, particularly as it relates to complying with the Americans with Disabilities Act. Accessible facilities: Structures accessible for most people with disabilities without assistance; facilities that meet Uniform Federal Accessibility Standards; Americans with Disabilities Act-accessible. [E.g., parking lots, trails, pathways, ramps, picnic and camping areas, restrooms, boating facilities (docks, piers, gangways), fishing facilities, playgrounds, amphitheaters, exhibits, audiovisual programs, and wayside sites.] Acetylcholinesterase: An enzyme that breaks down the neurotransmitter acetycholine to choline and acetate. Acetylcholinesterase is secreted by nerve cells at synapses and by muscle cells at neuromuscular junctions. Organophosphorus insecticides act as anti- acetyl cholinesterases by inhibiting the action of cholinesterase thereby causing neurological damage in organisms. -

Water Stewardship on Rangelands: a Manager's Handbook

Water Stewardship on Rangelands© A Manager’s Handbook Acknowledgements Acknowledgements This handbook was funded with the generous financial support of the Dixon Water Foundation. We are grateful to the Department of Environment and Society at Utah State University for additional financial support and to the students (listed below) in the department’s 2007 capstone course, Collaborative Problem-Solving for Environment and Natural Resources, for their significant and invaluable contributions in developing the approach and early drafts. This project could not have been completed without the support and participation of those who live and work in Spring Valley. In particular we are grateful to Mr. and Mrs. Dennis Eldrige, Mr. and Mrs. Hank Vogler, Troy Eldrige, Rick and Maggie Orr (NRCS), Curt Leet (NRCS), and Julie Thompson (ENLC) for spending time helping us get to know Spring Valley and the Tippett Pass allotment. We thank the Southern Nevada Water Authority, specifically Joe Guild, Zane Marshall, and Scott Leedham, for the time they spent discussing the project, sharing their knowledge, and providing us with valuable information. We sincerely appreciate the efforts of the members, employees, and friends of Carrus Land Systems who reviewed and contributed to this handbook, including Sheldon Atwood, Ben Baldwin, Roger Banner, Rick Danvir, Daniel K. Dygert, Diana Glenn, Bill Hopkin, Derek Johnson, Spring Valley, Nevada Mark Kossler, Charlie Orchard, Robert Peterson, Eric Sant, and Gregg Simonds. Photo: Nicole McCoy Lastly, this project would not have been possible without the initiative, enthusiastic participation, and valuable insights from Agee Smith and his family. Student Contributors Spencer Allred • Harold Bjork • Michael Bodrero • James Brower • Austin Catlin • Collin Covington • Mark Ewell • Jeremy Ivie • Gilbert Jackson • Matt Jemmett • Derek Johnson • Heather Phillips • John Reese • Laredo Rich • Steve Truelson • Doug Viehweg • Josh Winkler Nicole McCoy, Ph.D. -

Overview of Rangelands RANGELANDS an INTRODUCTION to WILD OPEN SPACES

Overview of Rangelands RANGELANDS AN INTRODUCTION TO WILD OPEN SPACES Rangelands An Introduction to Idaho’s Wild Open Spaces 2012 Rangeland Center Idaho Rangeland Resource Commission University of Idaho P. O. Box 126 P.O. Box 441135 Emmett, ID 83617 Moscow, ID 83844 (208) 398-7002 (208) 885-6536 [email protected] [email protected] www.idahorange.org www.uidaho.edu/range The University of Idaho Rangeland Center and the Idaho Rangeland Resource Commission are mutually dedicated to fostering the understanding and sustainable stewardship of Idaho’s vast rangeland landscapes by providing scientifically-based educational resources about rangeland ecology and management. Many people are credited with writing, editing, and developing this chapter including: Lovina Roselle, Karen Launchbaugh, Tess Jones, Ling Babcock, Richard Ambrosek, Andrea Stebleton, Tracy Brewer, Ken Sanders, Jodie Mink, Jenifer Haley and Gretchen Hyde. 2 Overview of Rangelands Rangelands Overview What are Rangelands? How Much Rangeland Is There? Rangelands of the World Rangeland Regions of North America Rangeland Vegetation Types of North America Mediterranean Region Pacific Northwest Great Basin Southwest Desert Great Plains Uses and Values of Rangelands What is Rangeland Management? History of Rangeland Use and Ownership Who Owns and Manages Rangelands? References and Additional Information What are Rangelands? What are rangelands? Rangelands are lands that are not: farmed, dense forest, entirely barren, or covered with solid rock, concrete, or ice. Rangelands are: grasslands, shrublands, woodlands, and deserts. Rangelands are usually characterized by limited precipitation, often sparse vegetation, sharp climatic extremes, highly variable soils, frequent salinity, and diverse topography. From the wide open spaces of western North America to the vast plains of Africa, rangelands are found all over the world, encompassing almost half of the earth’s land surface. -

Forest and Rangeland Soils of the United

Richard V. Pouyat Deborah S. Page-Dumroese Toral Patel-Weynand Linda H. Geiser Editors Forest and Rangeland Soils of the United States Under Changing Conditions A Comprehensive Science Synthesis Forest and Rangeland Soils of the United States Under Changing Conditions Richard V. Pouyat • Deborah S. Page-Dumroese Toral Patel-Weynand • Linda H. Geiser Editors Forest and Rangeland Soils of the United States Under Changing Conditions A Comprehensive Science Synthesis Editors Richard V. Pouyat Deborah S. Page-Dumroese Northern Research Station Rocky Mountain Research Station USDA Forest Service USDA Forest Service Newark, DE, USA Moscow, ID, USA Toral Patel-Weynand Linda H. Geiser Washington Office Washington Office USDA Forest Service USDA Forest Service Washington, DC, USA Washington, DC, USA ISBN 978-3-030-45215-5 ISBN 978-3-030-45216-2 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-45216-2 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2020 . This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the book’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the book’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.