Forced Rhubarb in West Yorkshire C.1852-2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seniors in Touch

July 2018 Vol. 10 Issue 7 Seniors In Touch “It means so much to stay in touch” A Sentimental Centennial Special Days in July by Allison Brunette 1 International Joke Day When you need advice, who 2 Build A Scarecrow Day better to listen to than someone older and wiser? No matter your 2 I Forgot Day age — old or young — time al- ways brings a unique perspective 2 World UFO Day on the way we should have done things. 5 Work-a-holic Day In an endearing video, CBC Ra- 10 Teddy Bear Picnic Day dio asked people of all ages — as young as 7 and as old as 93 — 11 Cheer up the Lonely Day to share their best piece of ad- vice for a person just a year 13 Fool's Paradise Day younger. 14 Bastille Day The brutally honest responses were both charming and wise, 15 Cow Appreciation Day covering everything from love and relationships, to money and 16 Fresh Spinach Day career, to finding your confi- Edgar Kuhlow admiring his cake. dence. 19 National Raspberry Pie Day Here are just a few: - Stop caring so much about what people think. They’re not thinking 20 Moon Day about you at all. Sincerely, a 47-year-old - A midlife crisis does not look good. Sincerely, a 48-year-old 22 Hammock Day - Always tell the truth (except in your online dating profile). Sincerely, a 51-year-old 22 Rat Catcher's Day - Spend all your money, or your kids will do it for you. Sincerely, an 85- 23 National Hot Dog Day year-old And the very best.. -

Employee Handbook

2 2020 014 Leeds City School System EMPLOYEE HANDBOOK ©Leeds City School System 1404 8th Street Leeds, Alabama 35094 School System 1404 8th Street Leeds, Alabama 35094 Leeds City Schools Promoting Achievement Respect and Success www.leedsk12.org Acknowledgment of Receipt 2020 I_______________________________________________________, an employee of (Print Name) Leeds City Schools hereby acknowledge by my signature that I have received, read and understand the Leeds City School System Employee Handbook. The Leeds City School System Employee Handbook is current at the time it is published and is not intended to supersede the Leeds City School System Policy Manual. The Leeds City School System Employee Handbook was sent to all employees via email. If you would like a paper copy, please make your request to Amy Terry at [email protected]. The Leeds City School System Employee Handbook and Leeds City School System Policy Manual are available online at www.leedsk12.org by clicking Department of Human Resources and scrolling to Documents. Signature of Employee Date This acknowledgment is to be returned to Amy Terry, Director of Student Services and Personnel. Leeds City School System 2020 EMPLOYEE HANDBOOK -- Page | 1 THIS PAGE IS INTENTIONALLY BLANK Leeds City School System 2020 EMPLOYEE HANDBOOK -- Page | 2 Statement of Non-Discrimination, Anti-Discrimination, and Anti-Harassment Policy The Leeds City School System does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, sex, creed, age, marital status, disability, or any other reason prohibited by state or federal law in its educational programs, activities, or employment policies and provides equal access to the Boy Scouts and other designated youth groups as required by Title VI, Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, Title IX of the 1972 Educational Amendments, Section 504 of the Federal Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the American with Disabilities Act (ADA). -

Display Wetherby

Welcome to Display Wetherby Hello, we are Display UK, part of the Smur�t Kappa Group. When you visit a Display UK site you will notice how we pride ourselves on commitment to our health and safety policies. Please take time to read our visitor safety notices and take care travelling to our site. Above all, we wish you a great visit. Please enjoy your visit 46 A168 cars A1(M) Scriftain Lane HGVs Wetherby A168 A1(M) Sandbeck Approach B1224 Sandbeck Lane, Wetherby, Yorkshire, LS22 7YD B6164 W Tel: 01937 868200 ether b B1224 y Ro B1224 a d B1224 From the North: WE B1224 Leave the A1(M) at Junction 46, take the B1224 exit signed D H earne Cr ud E ARE s s on York/Wetherby. At the roundabout take the 4th exit onto B1224. k G South Vi D eersto W a ay r of de t n Turn left at the next roundabout onto A168. Follow this road, at the n s e e HERE w A168 Ri d g roundabout take the 3rd exit onto Sandbeck Lane. Destination will e Sandbeck Lane Deighton Bar 46 be on the right. e Kirk Deighton Deighton h Yorkshir HarrogateNort Gates Primary eeds B1224 y L R School Wetherb a cec Badger o urse Fos Hunters W s venue k B A W e n ndbeck Lane e ppleb ood G Sa From the South: c h Ai w al n ood Ba y W sty Vie k w ood l a A168 Take the M1 North, keep left at the fork to stay on the M1, follow d ay e Otter Ri w s signs for Leeds (East). -

Oral Health Needs Assessment for Wakefield

Oral Health Needs Assessment Wakefield District Ian Walker Public Health Specialty Registrar March 2015 1 1.0 Executive summary Over the last thirty years there have been significant improvements in oral health in the UK, however many people still suffer the pain and discomfort of oral diseases which are largely preventable and remain a major public health problem. Decaying teeth constitutes the number one, most prevalent disease globally, with tooth decay (dental caries) and gum disease (periodontal disease) being the most common dental problems in the UK. There is a cumulative effect if unchecked in early stages of life, which leads to more pervasive decay in adulthood and higher chances of extensive tooth loss in later life. The distribution and severity of oral diseases varies between and within countries and regions and whilst sections of the British population enjoy very good levels of oral health, stark inequalities exist with some of the poorest and most disadvantaged sections of society facing significant oral health problems. This oral health needs assessment (OHNA) provides a detailed picture of the oral health needs of the Wakefield district and the commissioned dental services and oral health promotion services to meet those needs. It identifies gaps in provision and identifies key issues to be prioritised and addressed within future work on oral health in the district. Oral health of children 5 year olds in Wakefield are now 1½ times more likely to have some dental decay than 5 year olds across England. For an average group of 100 Wakefield children aged 5, there would be 41 with some dental decay, compared with 28 from an average group of 100 children from England. -

Artist's Notes the Rhubarb Triangle & Other Stories: Photographs by Martin Parr

ARTIST’S NOTES THE RHUBARB TRIANGLE & OTHER STORIES: PHOTOGRAPHS BY MARTIN PARR www.hepworthwakefield.org THE RHUBARB TRIANGLE & OTHER STORIES: PHOTOGRAPHS BY MARTIN PARR 4 February - 12 June 2016 INTRODUCTION and leisure events, or commenting on the consumerism of western culture in the documentation of everyday Martin Parr, the best-known British photographer objects and food in his series Common Sense (1995 – 9) of his generation, was born in Epsom, Surrey in exhibited in Gallery 10, themes of work and leisure can 1952. As a young boy, Parr’s interest in photography be traced throughout his work. was encouraged by his grandfather, George Parr, a Yorkshireman and keen amateur photographer. His Parr’s earlier work focussed on small social groups grandfather gave him his first camera and taught him within Britain, shown within series such as The Non- how to take photographs, process the film and make Conformists (1975 – 80) on display in Gallery 7. Over prints. Parr followed this interest and went on to study the past twenty years he has increasingly worked photography at Manchester Polytechnic from 1970 – 73. abroad, and his work has reflected this change, exploring themes of globalisation and the rise of Since studying in Manchester Parr has worked on international tourism, which can be seen within his work numerous photographic projects; he has developed exhibited in Gallery 10. an international reputation for approach to social documentary, and his input to photographic culture Changing photography and use of technology: within the UK and abroad. He also makes films, curates exhibitions and festivals, teaches, is president Parr’s first major series of work,The Non-Conformists, of the co-operative agency Magnum Photos, and was photographed in black and white, partially for collaborates with publishers to produce books on other its suitability to the subject and the nostalgic look at photographers. -

Product Catalog STANDS

LEEDS Product PRECISION INSTRUMENTS Catalog Microscope accessories, bases, stands, lighting, mounts & tables June 2017 www.leedsmicro.com T a b l e o f C o n t e n t s Part Number Description Page # STANDS LMS-100 Complete Boom stereoscope stand 4 LMA-036A Drop prevention collar 5 LMS-150 Heavy boom base & 24” column 5 LMS-197 14” Vertical column with table clamp 5 LMS-197K C-Clamp Mount with Articulating arm 5 LMS-198 14” Vertical column with flange mount 5 LMS-198-24 24” Vertical column with flange mount 5 LMS-200 Boom base & 14” column 5 LMS-200B Extra Weight for LMS-200 Boom Stand 5 LMS-200-24 Boom stand base & 24” column 5 LMS-300 Articulating boom arm - double jointed fold away design 5 BASES LMS-340LED BF/DF transillumination LED base 6 LPI-S-0204 400mm pillar 6 LMS-SZX-R Drop prevention collar 6 LMS-EHR2 Ergo head riser 6 LMS-LEDS LED Spot Illuminator 7 LMS-LEDS-3 Mounting Adapter for LMS-340LED with Olympus 32mm post 7 LMS-225LEDSL LED Transmitted Light Base 7 LMS-225ZEPLT Top Mounting plate for LMS-225LED 7 LMS-LEDS LED Spot light only for LMS-225LED 7 LMS-LEDSK LED Spot light kit, including base, arm & power control 7 LMS-LEDS-2 Mounting adapter for Olympus SZ2-ST stand 7 LMS-LEDS-4 Mounting adapter for LMS-225LEDSL -Accu-Scope 7 LIGHTING LRL-410 High clearance ringlight - 4-ft length 8 LMA-060 Thread adapter 8 LMA-061 Ferrule for Dolan Jenner 180 8 LMA-063 Ferrule for Fostec 8 LMS-LEDS LED Spot Illuminator 9 LMS-LEDSK LED Spot Illuminator Kit 9 LMS-LEDS-2 Mounting Adapter for LMS-225LEDSL with Olympus SZ2-ST Stand 9 LMS-LEDS-3 -

May 2021 FOI 2387-21 Drink Spiking

Our ref: 2387/21 Figures for incidents of drink spiking in your region over the last 5 years (year by year) I would appreciate it if the figures can be broken down to the nearest city/town. Can you also tell me the number of prosecutions there have been for the above offences and how many of those resulted in a conviction? Please see the attached document. West Yorkshire Police receive reports of crimes that have occurred following a victim having their drink spiked, crimes such as rape, sexual assault, violence with or without injury and theft. West Yorkshire Police take all offences seriously and will ensure that all reports are investigated. Specifically for victims of rape and serious sexual offences, depending on when the offence occurred, they would be offered an examination at our Sexual Assault Referral Centre, where forensic samples, including a blood sample for toxicology can be taken, with the victim’s consent, if within the timeframes and guidance from the Faculty for Forensic and Legal Medicine. West Yorkshire Police work with support agencies to ensure that all victims of crime are offered support through the criminal justice process, including specialist support such as from Independent Sexual Violence Advisors. Recorded crime relating to spiked drinks, 01/01/2016 to 31/12/2020 Notes Data represents the number of crimes recorded during the period which: - were not subsequently cancelled - contain the search term %DR_NK%SPIK% or %SPIK%DR_NK% within the crime notes, crime summary and/or MO - specifically related to a drug/poison/other noxious substance having been placed in a drink No restrictions were placed on the type of drink, the type of drug/poison or the motivation behind the act (i.e. -

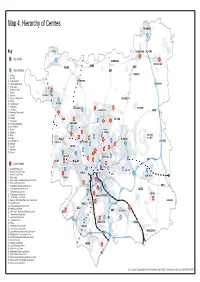

Map 4. Hierarchy of Centres WETHERBY

Map 4. Hierarchy of Centres WETHERBY 27 Key OTLEY COLLINGHAM A1 (M) 9 City Centre 4 22 HAREWOOD BOSTON SPA A659 A660 A58 Town Centres A61 1 Armley BARDSEY 2 Bramley 3 Chapel Allerton BRAMHOPE 4 Colton (Selby Road) BRAMHAM 5 Cross Gates 6 Dewsbury Road 12 7 Farsley 9 8 Garforth GUISELEY 9 Guiseley, Otley Road 28 SCARCROFT 10 Halton 11 Harehills Lane YEADON 12 Headingley COOKRIDGE 1 29 THORNER 13 Holt Park 13 ALWOODLEY A64 14 Horsforth, Town Street 27 15 Hunslet 16 Kirkstall A65A6A65 18 A6120A6A61661201212020 17 Meanwood 19 26 3311 18 Middleton Ring Road HORSFORTHHORSFOS RTHRTTHTH 19 Moor Allerton 141 20 Morley CHAPELCHAC PEL 21 Oakwood 6 AALLALLERTONERTRTR ONN 17 BARWICKBARARW 22 Otley 3 23 Pudsey 14 3333 1177 IN ELMETELM A657A6577 25 SEACROFTSEASE CRROR FTT 24 Richmond Hill 221 A1 (M) CALVERLEYCACALC VERRLEYY HEADINGLEYHHEAHEADIND GLLEY 25 Rothwell 1212 16 26 RODLEYRODR LEYY 26 Seacroft 133 8 27 Wetherby 1166 1199 28 Yeadon 7 2 28 FARSLEYFARARSLSLES Y HAREHILLSHAREHILLS 11 5 2121 5 M1 A647A6477 300 BRAMLEYBRABBRRARAMMLEY Local Centres 22 24 1 Alwoodley King Lane 23 1 CITYY 10 2 Beeston Hill Local Centre HALTONHALTON 8 7 ARMLEY CENTRECCENENTRTRETR 4 3 Beeston Local Centre GARFORTH 4 Boston Spa PUDSEY 5 Burley Lodge (Woodsley Road) Local Centre 15 6 Butcher Hill Local Centre 23 7 Chapeltown (Pudsey) Local Centre A63 2 15 8 Chapeltown Road Local Centre 6 A642 9 Collingham Local Centre 10 Drighlington Local Centre 3 KIPPAX BEESTON M621 11 East Ardsley Local Centre 20 12 Guiseley Oxford Road/Town Gate Town Centre 32 LEDSHAM 13 Harehills Corner -

Syndromic Surveillance for the State of Louisiana

Infectious Disease Epidemiology Section Office of Public Health, Louisiana Dept. of Health & Hospitals 800-256-2748 (24 hour number) www.infectiousdisease.dhh.louisiana.gov Louisiana Early Event Detection System Emergency Department and Urgent Care Syndromic Surveillance for the State of Louisiana Louisiana Office of Public Health Infectious Diseases Epidemiology Section Rev. 4/12/2016 Page 1 LEEDS: Syndromic Surveillance for the State of Louisiana Louisiana Office of Public Health, Infectious Diseases Epidemiology Section Table of Contents 1. Definition of Syndromic Surveillance…………….……………………………………………….………..3 2. Purpose of Syndromic Surveillance……………….……………………………………………….………..3 3. Authority…………………………………………………………………………………………….……....4 4. Privacy and Confidentiality………………………………………………………………………………....4 5. Syndromic Surveillance is Reportable by the Sanitary Code……………………………………………….4 6. Meaningful Use ……………………………………………………………………………………….…….4 7. Syndromic Surveillance in Louisiana…….…………..……………………………………………………..4 8. Louisiana Early Event Detection System (LEEDS) ……………………………………………….……….5 9. Data Collection……..……………………………………………………………………………………….6 10. Follow-up of Aberrations Identified by LEEDS…………………………………………………………….6 11. Viewing LEEDS Reports…………………………………………………………………………………....6 12. BioSense – National Syndromic Surveillance………………………………………………………………6 Appendices I. LEEDS File Specifications……..…………………………………………………………………………….7 CSV format ……………………………………………………………………………………..…...8 HL7 format ……………………………………………………………………………….……........9 Sample HL7 Message………………………………………………………………………………10 -

Explore Woodlesford Lock

Explore Woodlesford Lock Located just five miles from Leeds, Woodlesford Lock on the Aire & Calder Navigation, is one of the best Thwaite Mills Fishponds Lock places to escape the city and enjoy Museum country walks. & Leeds re Ai er Riv Access to Rothwell Air e & Country Park C Woodlesford Lock al der Na Rothwell vig ati Country Park on Pottery Lane A642 The Goit Aberford Road Little adventures on your doorstep Two Pointers Lemonroyd Lock Beechwood and St Aidan’s Centre Nature Reserve STAY SAFE: Village Midland Hotel Stay Away From green & local facilities the Edge Map not to scale: covers approx 0.5 miles/0.8km A little bit of history The Aire & Calder Navigation was built to connect Leeds to the Humber and the North Sea. Unique to this navigation were ‘Tom Puddings’, huge open containers for carrying coal, linked together and pushed along by tugs. The waterway still carries commercial traffic but Best of all today, it makes its way through peaceful countryside. it’s FREE!* Five things t o do at Wo Picnic Pack binoculars and trackodl edown exotic wooden sford Information wildlife such as elephant, antelope, giraffe, Lgorilla,ock deer Woodlesford Lock and the very rare Gruffalo! Woodlesford Use the bird screen to watch a huge variety of bird West Yorkshire life. Look out for sand martins on the riverbank, the LS26 8PU blue flash of a kingfisher or spot a forked-tailed red kite circling in the sky. Parking (free & Visit Thwaite Mills, a water-powered mill which at P&D) various times milled rape oil for lubrication and Toilets (in hotel, lighting, and crushed wood for dyes and whiting for pubs and cafés household products in village) Keep a look about for working boats and barges Café Take a walk. -

DUNGEON LANE FARM Dungeon Lane, Oulton, Rothwell, Leeds LS26 8HJ

DUNGEON LANE FARM Dungeon Lane, Oulton, Rothwell, Leeds LS26 8HJ DUNGEON LANE FARM DUNGEON LANE FARMHOUSE: SITTING ROOM Dungeon Lane, Oulton, Rothwell, Leeds LS26 8HJ A stone built property, under a composition tiled roof, with 34’3” x 14’1” uPVC double glazed windows throughout offering the Open brick fireplace with timber mantel, wood burning stove, Guide Price: £600,000 following accommodation: 2 no. radiators, exposed timber trusses, dual aspect double glazed windows. ON THE GROUND FLOOR ADJOINING BEDROOM/STUDY: A country residence situated in a rural ENTRANCE PORCH: 7’8” x 14’4” 7’3” x 4’6” setting with far reaching views over Exposed beam ceiling, carpeted. Double glazed leaded windows, tiled floor. open countryside but within easy reach KITCHEN / BREAKFAST ROOM AND STUDY: of local amenities and good transport INNER ENTRANCE HALL Kitchen/Dining area with fitted floor and wall units, central links. The property offers an ideal 18’1” X 11’2” breakfast bar, fitted “Belling Form” 4 hob cooker, stone Brick fireplace, and multi fuel stove, Stone flagged floor, fireplace with timber mantel and wood burning stove, double investment or an opportunity Beamed ceiling, Steps up to kitchen and steps down into glazed leaded windows to south. 2 no. radiators, double for those with small-holding and Sitting Room, 2 no. radiators stainless steel sink and drainer, plumbing for washing machine and access to cellar. equestrian interests. CLOAKROOM: With wash hand basin, tiled recess, W.C, heated towel rail, CONSERVATORY: radiator. 18’ x 10’10” IN ALL EXTENDING TO 6.74 ACRES OR SMALL CUPBOARD: Stone flag floor, double glazed upvc windows, block sleeper THEREABOUTS A walk in cupboard, housing the Worcester Greenstar walls. -

Leeds - Halifax Mondays to Fridays 2W01AG 1J01NT 2K02AG 1D70FA 1B13AG 1J03NT 2K03AG 1D71FA 2R34LF 1B15AG

York / Hull - Leeds - Halifax Mondays to Fridays 2W01AG 1J01NT 2K02AG 1D70FA 1B13AG 1J03NT 2K03AG 1D71FA 2R34LF 1B15AG From To HDRSFLD MNCRVIC CHST BLCKPLN MNCRVIC CHST YORK BLCKPLN York d - - - - 0518 - - - - 0612 Ulleskelf - - - - - - - - - - Church Fenton - - - - 0529 - - - - 0629 Hull d - - - - - - - - 0545 - Hessle - - - - - - - - - - Ferriby - - - - - - - - - - Brough - - - - - - - - 0557 - Broomfleet - - - - - - - - - - Gilberdyke - - - - - - - - 0605 - Eastrington - - - - - - - - 0609 - Howden - - - - - - - - 0614 - Wressle - - - - - - - - 0618 - Selby a - - - - - - - - 0627 - Selby d - - - - - - 0547 - - - South Milford - - - - - - 0558 - - - Micklefield - - - - 0536 - 0604 - - 0635 East Garforth - - - - 0540 - 0609 - - 0639 Garforth - - - - 0542 - 0611 - - 0641 Cross Gates - - - - 0546 - 0616 - - 0646 Leeds a - - - - 0554 - 0624 - - 0653 Leeds d 0501 0512 0522 0542 0557 0612 0627 0642 - 0657 Bramley a 0509 0518 0530 0548 - 0618 0635 0648 - - New Pudsey a 0513 0522 0534 0552 0605 0622 0639 0652 - 0706 Bradford Interchange a 0522 0530 0543 0601 0614 0630 0648 0701 - 0715 Halifax a 0538 0543 0559 0616 0627 0643 0703 0716 - 0728 York / Hull - Leeds - Halifax Mondays to Fridays 1J05NT 2K05AG 2R38MG 2T91AG 1D72FA 1B17AG 2K97LF 2K07AG 1J07NT 2T93AG From To MNCRVIC YORK CHST BLCKPLN MNCRVIC York d - - - 0708 - 0710 - - - 0746 Ulleskelf - - - - - 0718 - - - 0756 Church Fenton - - - - - 0727 - - - 0801 Hull d - 0610 0619 - - - - 0715 - - Hessle - - - - - - - - - - Ferriby - - - - - - - - - - Brough - 0622 0631 - - - - 0727 - - Broomfleet