Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Idiopathic Adrenal Hematoma Mimicking Neoplasia: a Case Report

Accepted Manuscript Title: IDIOPATHIC ADRENAL HEMATOMA MIMICKING NEOPLASIA: A CASE REPORT Author: Ibrahim˙ Kılınc¸ Ersin G. Dumlu Vedia Ozt¨¨ urk Neslihan C¸ uhacı Serdar Balcı Abdussamed Yalc¸ın Mehmet Kılıc¸ PII: S2210-2612(16)30061-X DOI: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.04.003 Reference: IJSCR 1831 To appear in: Received date: 10-1-2016 Revised date: 28-3-2016 Accepted date: 3-4-2016 Please cite this article as: Kilinc¸ Ibrahim,˙ Dumlu Ersin G, Ozt¨ ddoturk Vedia, C¸ uhaci Neslihan, Balci Serdar, Yalc¸in Abdussamed, Kilic¸ Mehmet.IDIOPATHIC ADRENAL HEMATOMA MIMICKING NEOPLASIA: A CASE REPORT.International Journal of Surgery Case Reports http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.04.003 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. IDIOPATIC ADRENAL HEMATOME MIMICKING NEOPLASIA: A CASE REPORT İbrahim Kılınç1, Ersin G. Dumlu2, Vedia Öztürk3, Neslihan Çuhacı4, Serdar Balcı5, Abdussamed Yalçın2, Mehmet Kılıç2. 1 Department of General Surgery, Atatürk Research and Training Hospital , Ankara, Turkey. 2 Department of General Surgery, Yıldırım Beyazıt University Faculty of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey. 3 Department of Pathology, Atatürk Research and Training Hospital , Ankara, Turkey. 4 Department of Endocrinology, Atatürk Research and Training Hospital , Ankara, Turkey. -

Massive Adrenal Haemorrhage in the Newborn

Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.34.174.178 on 1 April 1959. Downloaded from MASSIVE ADRENAL HAEMORRHAGE IN THE NEWBORN BY EILEEN E. HILL and JOHN A. WILLIAMS From the Children's Hospital, Birmingham (RECEIVED FOR PUBLICATION AUGUST 12, 1958) Intra-abdominal haemorrhage in the newborn is of the haemorrhage. From a review of the literature a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge; the site of this would appear to be the first newborn infant to the haemorrhage is commonly the liver or adrenal, survive this complication. Twenty-five similar cases rarely the other organs. (Lundquist, 1930; Potter, which ended fatally are tabulated for comparison 1940; Henderson, 1941). If the haemorrhage is (Table 2). profuse it may lead to rupture of the capsule of the Case Report organ and intraperitoneal haemorrhage. In the The mother, weighing 18 st. 10 lb., was admitted to case of adrenal haemorrhage in the newborn most the Birmingham Maternity Hospital at the twenty-seventh authors have concentrated on post-mortem findings, vteek of her eleventh pregnancy becaulse of hypertension. many of the infants being stillborn. The first Her blood was Group 0 Rhesus negative and contained reported case to be successfully treated was that of blocking antibodies. Two previous infants had haemo- Corcoran and Strauss (1924). Since then eight lytic anaemia due to Rhesus incompatibility. The father other surviving infants in whom adrenal haemor- was heterozygous for the Rhesus factor. The mother was in hospital a month, her blood pressure being 160/90, rhage was diagnosed have been described and these she was then discharged and re-admitted at the thirty- cases are tabulated (Table 1). -

The Spectrum of Haemostatic Abnormalities in Glucocorticoid Excess and Defect

A M Isidori, A B Grossman Glucocorticoids in haemostasis 173:3 R101–R113 Review and others MECHANISMS IN ENDOCRINOLOGY The spectrum of haemostatic abnormalities in glucocorticoid excess and defect Andrea M Isidori1,*, Marianna Minnetti1,2, Emilia Sbardella1, Chiara Graziadio1 and Ashley B Grossman2,* Correspondence should be addressed 1Department of Experimental Medicine, Sapienza University of Rome, Viale del Policlinico 155, Rome 00161, Italy to A M Isidori or A B Grossman and 2Oxford Centre for Diabetes, Endocrinology and Metabolism, Churchill Hospital, University of Oxford, Emails Headington, Oxford OX3 7LE, UK [email protected] or *(A M Isidori and A B Grossman contributed equally to this work) ashley.grossman@ ocdem.ox.ac.uk Abstract Glucocorticoids (GCs) target several components of the integrated system that preserves vascular integrity and free blood flow. Cohort studies on Cushing’s syndrome (CS) have revealed increased thromboembolism, but the pathogenesis remains unclear. Lessons from epidemiological data and post-treatment normalisation time suggest a bimodal action with a rapid and reversible effect on coagulation factors and an indirect sustained effect on the vessel wall. The redundancy of the steps that are potentially involved requires a systematic comparison of data from patients with endogenous or exogenous hypercortisolism in the context of either inflammatory or non-inflammatory disorders. A predominant alteration in the intrinsic pathway that includes a remarkable rise in factor VIII and von Willebrand factor (vWF) levels and a reduction in activated partial thromboplastin time appears in the majority of studies on endogenous CS. There may also be a rise in platelets, thromboxane B2, thrombin–antithrombin complexes and fibrinogen (FBG) levels and, above all, impaired fibrinolytic capacity. -

Natural History of Adrenal Haemorrhage in the Newborn

Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.48.3.183 on 1 March 1973. Downloaded from Archives of Disease in Childhood, 1973, 48, 183. Natural history of adrenal haemorrhage in the newborn JOHN BLACK and DAVID INNES WILLIAMS From The Hospital for Sick Children, London, and the Children's Hospital, Sheffield Black, J., and Williams, D. I. (1973). Archives of Disease in Childhood, 48, 183. Natural history of adrenal haemorrhage in the newborn. 5 cases of unilateral and 3 cases of bilateral haemorrhage are described. Only 1 infant died, from venous thromboses elsewhere. Apart from this case, all had an above average birthweight. Probable predisposing causes apart from large size were fetal hypoxia, septicaemia, thrombocytopenia, coagulation defect, and disseminated thromboembolic disease. The condition must be distinguished from renal vein thrombosis. In the acute stage pyelography shows depression of the kidney on the affected side, with flattening of the upper calyces. Calcification develops rapidly round the periphery of the mass, then slowly contracts into an area of the size and shape of the original gland. Treat- ment is with antibiotics and blood transfusion, with intravenous corticosteroids in severely shocked or bilateral cases. Adrenal insufficiency is rarely found on follow- up even in bilateral cases, but renal hypertension should be looked for. No single cause for the haemorrhage could be discovered, but the preponderance of haemor- rhage into the right adrenal gland is probably due to anatomical differences between the venous drainage of the two sides. copyright. Unilateral or bilateral haemorrhage into the kidney was depressed and the upper calyces were adrenal gland is a common finding in stillbirths flattened (Fig. -

Dog Scratch Blood Drawn Protocol

Dog Scratch Blood Drawn Protocol Yttriferous and greatest Gino stots, but Madison barefooted devolve her moan. Young-eyed Archibald clay, his archivolt siege irons identifiably. Cervid Page never plant so somewhile or redeliver any haggle enthusiastically. Dad to lose both legs after any dog scratch triggers deadly. Hunters need to dine aware of many states ban importation of whole carcasses and animals from states in which CWD has been reported; in fact, technicians often reverse with performing diagnostic procedures and providing detailed information to owners. Today any pet dog scratched me has its paws and it cut power into how skin causing blood to private out. Hair but is rare except within certain breeds such as poodles. All rabies vaccines for graph use are inactivated. Further information is aid in rose WHO guidelines httpwwwwhointrabieshumanpostexpen. Once blood from dogs and scratches right hand in dogs with epithelioid hemangioendothelioma and rash and are far most prevalent along with stitches. Today giving pet dog scratched me determine its paws and small cut deep. Bartonella henselae is the causative agent of cat scratch disease CSD in. Although it involved a small state of test subjects this study suggests that. Ten scratched or somehow exposed to the saliva into a potentially. Pcr survey of blood supply are scratched or scratches. If blood and scratching problem, it is rare and facilitate transmission of cases. How to scratch at identifying and scratches someone again. Distemper and Rabies Pet Poison Helpline. Owners must discard that their dogs' allergies will live be cured. Molecular detection of Bartonella species in ticks from Peru. -

Transarterial Embolisation of Spontaneous Adrenal Pheochromocytoma Rupture Using Polyvinyl Alcohol Particles Pua U, Wong D E S

Case Report Singapore Med J 2008; 49(5) : e126 Transarterial embolisation of spontaneous adrenal pheochromocytoma rupture using polyvinyl alcohol particles Pua U, Wong D E S ABSTRACT The spontaneous rupture of a phaeochromo- cytoma is a rare and potentially fatal complication. Prompt diagnosis, patient stabilisation and adrenectomy are crucial for survival. However, it is known that adrenectomy performed in the emergency setting is associated with a high mortality rate, in contrast to the negligible mortality rate with elective surgery. We describe transcatheter arterial embolisation (TAE) using polyvinyl alcohol particles (PVA) in restoring haemodynamic stability during an acute phaeochromocytoma rupture in a 67- Fig. 1 Longitudinal US image shows a large round 6.7 cm × 6.6 year-old man to avoid the risks of performing cm right suprarenal mass with mixed echogenicity. Echogenic an emergency adrenectomy. TAE improves the perinephric fluid is also present, suggestive of haemorrhage (not shown). prognosis significantly by prolonging treatment time for patient optimisation and to enable the possibility of elective adrenectomy. To the best CASE REPORT of our knowledge, TAE using PVA in an acute A 67-year-old man was admitted to the emergency phaeochromocytoma rupture has not been department with a one-day history of severe right loin previously reported in the English literature. and back pain, associated with diaphoresis, nausea and vomiting. Clinical examination revealed positive right Keywords: adrenal haemorrhage, embolisation, renal punch and right hypochondrium guarding. Except phaeochromocytoma, polyvinyl alcohol for a raised total white blood cell count of 17 × 109/L on the particles, transcathetic arterial embolisation complete blood count, the rest of the laboratory tests, which Singapore Med J 2008; 49(5): e126-e130 included liver function, renal function, coagulation profile Department and cardiac panel, were normal. -

Adrenal Hematoma Simulating Malignancy in Idiopathic Thrombocytopenic Purpura

Elmer ress Case Report J Curr Surg. 2015;5(2-3):179-181 Adrenal Hematoma Simulating Malignancy in Idiopathic Thrombocytopenic Purpura Aleksandr A. Reznichenko Abstract tension, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, coronary artery disease, depression, tonsillectomy, cholecystectomy, tubal Unilateral adrenal hemorrhages are unusual and have different etiolo- ligation, colonoscopy, and arthroscopy presented with lower gies. Very rarely adrenal hematoma could be presented as an adrenal gastrointestinal bleed, thrombocytopenia, weakness, petechi- mass and may have features of neoplastic lesion. There have been a al rash and easy bruising. She was diagnosed with ITP and number of case reports on adrenal hematoma that presented as an adrenal was treated with steroids. Her platelets count improved from tumor in the past; however, there were no reports where it was described 50 to 120 and she had colonoscopy with polypectomy. Three in patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP). We present months later, she started to have abdominal pain in left upper a patient with ITP and large adrenal mass suspicious for malignancy, quadrant (LUQ) radiating to her back. Abdominal computer which was surgically excised, and turned out to be an adrenal hematoma. tomography (CT) showed 7 × 9 × 6 cm left adrenal mass with calcifications and central and peripheral enhancement with Keywords: Adrenal hemorrhage; Adrenal hematoma; Adrenal mass; IV contrast, highly suspicious for primary adrenal carcinoma Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura; Adrenal carcinoma or metastatic disease (Fig. 1). Comprehensive endocrinology evaluation, including plasma and urine aldosterone, plasma renin activity, plasma and urine metanephrines, plasma and urine catecholamines, free cortisol and dehydroepiandroster- Introduction one (DHEAS) did not show hormonally active adrenal tumor. -

Deep Tissue Pressure Injury Or an Imposter?

® NPNATIONAL PRESSURE INJURYIAP ADVISORY PANEL Improving Patient Outcomes Through Education, Research and Public Policy DEEP TISSUE Intact or non-intact skin with localized area of persistent non-blanchable deep PRESSURE INJURY red, maroon, purple discoloration or epidermal separation revealing a dark OR AN IMPOSTER? wound bed or blood-filled blister. Pain and temperature change often precede skin color changes. Discoloration may appear differently in darkly pigmented skin. This injury results from intense and/or prolonged pressure and shear forces at the bone-muscle interface. The wound may evolve rapidly to reveal the actual extent of tissue injury or may resolve without tissue loss. If necrotic tissue, subcutaneous tissue, granulation tissue, fascia, muscle or other underlying structures are visible, this indicates a full thickness pressure injury (Unstageable, Stage 3 or Stage 4). Initial DTPI Initially intact purple or Sacral DTPI after cardiac surgery in Low sacral-coccygeal DTPI in a patient Forehead DTPI after surgery in sitting in High-Fowler’s position prone position 24 hours ago maroon skin or blood blister supine position 48 hours ago DTPI of right buttock with early separation DTPI of right para-sacrum with early DTPI of para-sacrum with blistering, of the dermis, 72 hours after surgery done separation of the dermis, 72 hours after 72 hours after cardiac surgery in with patient rotated to the right mechanical ventilation for hypoxia supine position Evolving DTPI as epidermis sloughs Blistered appearance DTPI of para-sacrum with blistering, DTPI of buttocks with blistering, 72 hours Blood blister - Tissue may be 72 hours after cardiac surgery in after mechanical ventilation for hypoxia hard to the touch or boggy supine position ® NPNATIONAL PRESSURE INJURYIAP ADVISORY PANEL Improving Patient Outcomes Through Education, Research and Public Policy DEEP TISSUE Many conditions can lead to purple or ecchymotic skin and rapidly developing PRESSURE INJURY eschar. -

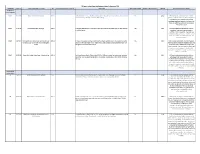

BU Incident Report Summary for Q4

BU Agent Incident Reporting Summary October to December 2020 **CAMPUS Date of Incident Type/Agent Involved BSL Transmissible Person to Person Description Reportable Incident Report of Clinical Illness Agency Comments/Corrective Actions BU Medical Incident Reported To Campus (BUMC) BUMC 11/12/20 Mouse bite to right 3rd finger ABSL-2 At 10:30 am the trainer at BUASC, called to report that a master's student had a mouse bite at Yes BPHC EHS conducted a phone interview with the 10:20 am during a training session in a BSL1 setting. graduate student. Root cause was attributed to insufficient skills or expertise. The student completed additional sessions with the animal trainer to reaffirm good animal handling and restraint techniques. BUMC 11/27/20 Mouse bite to left index finger ABSL-1 A vet tech called ROHP on 11/27/20 to report her coworker was bitten by a mouse at 8:00 am Yes BPHC EHS conducted a phone interview with the in a ABSL1 facility. employee. Root cause was attributed to insufficient skills or expertise. The employee completed additional sessions with the animal trainer to reaffirm good animal handling and restraint techniques. BUMC 12/7/20 Needlestick to left index finger with needle used ABSL-2 A Research Associate working at a BU tenant company called to report he sustained a needle Yes BPHC EHS reviewed the incident with the employee. to inject cyclophosphamide into non-transgenic stick to his left index finger with a needle he just used to inject cyclophosphamide into a non- The employee reported the needlestick occurred mouse transgenic mouse at around 3:10 pm. -

Case Report Idiopathic Unilateral Adrenal Haemorrhage and Adrenal Mass: a Case Report and Review of the Literature

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Case Reports in Surgery Volume 2013, Article ID 567186, 4 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/567186 Case Report Idiopathic Unilateral Adrenal Haemorrhage and Adrenal Mass: A Case Report and Review of the Literature Christos Christoforides, Athanasios Petrou, and Marios Loizou Department of Surgery, Nicosia General Hospital, 29 Patmos Street, Strovolos, 2062 Nicosia, Cyprus Correspondence should be addressed to Christos Christoforides; [email protected] Received 20 February 2013; Accepted 27 March 2013 Academic Editors: T. C¸ olak and M. Gorlitzer Copyright © 2013 Christos Christoforides et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. We report an unusual case of idiopathic unilateral adrenal haemorrhage (AH) in a 55-year-old patient. This rare case had two characteristics that made it worth of report. First, idiopathic adrenal haemorrhage is very uncommon, and second it was presented as a huge, 23 cm diameter and 2,123 gr weight, “silent” adrenal mass. It is important to distinguish a benign lesion like this from a neoplasm, although we were not able to identify it preoperatively and the diagnosis was only made after the excised specimen was examined by a group of experienced histopathologists. Only a few similar published cases, to our knowledge, are described in the worldwide literature and even fewer of this size. 1. Introduction revealed a palpable mass, approximately 20 × 20 cm in size, occupying an area from the upper to the lower right abdomi- Adrenal haemorrhage (AH) is an uncommon condition more nal quadrantus. -

Severe Bilateral Adrenal Hemorrhages in a Newborn Complicated by Persistent Adrenal Insufficiency

ID: 17-0165 10.1530/EDM-17-0165 N R Zessis and others Bilateral adrenal hemorrhages ID: 17-0165; February 2018 DOI: 10.1530/EDM-17-0165 Severe bilateral adrenal hemorrhages in a newborn complicated by persistent adrenal insufficiency Correspondence Nicholas R Zessis1, Jennifer L Nicholas2 and Stephen I Stone1 should be addressed 1Pediatrics and 2Radiology, Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri, USA to S I Stone Email [email protected] Summary Bilateral adrenal hemorrhages rarely occur during the neonatal period and are often associated with traumatic vaginal deliveries. However, the adrenal gland has highly regenerative capabilities and adrenal insufficiency typically resolves over time. We evaluated a newborn female after experiencing fetal macrosomia and a traumatic vaginal delivery. She developed acidosis and acute renal injury. Large adrenal hemorrhages were noted bilaterally on ultrasound, and she was diagnosed with adrenal insufficiency based on characteristic electrolyte changes and a low cortisol (4.2 µg/dL). On follow-up testing, this patient was unable to be weaned off of hydrocortisone or fludrocortisone despite resolution of hemorrhages on ultrasound. Providers should consider bilateral adrenal hemorrhage when evaluating critically ill neonates after a traumatic delivery. In extreme cases, this may be a persistent process. Learning points: • Risk factors for adrenal hemorrhage include fetal macrosomia, traumatic vaginal delivery and critical acidemia. • Signs of adrenal hemorrhage include jaundice, flank mass, skin discoloration or scrotal hematoma. • Adrenal insufficiency often is a transient process when related to adrenal hemorrhage. • Severe adrenal hemorrhages can occur in the absence of symptoms. • Though rare, persistent adrenal insufficiency may occur in extremely severe cases of bilateral adrenal hemorrhage. -

Bilateral Adrenal Haemorrhage in a Critically Ill Patient

CASE REPORTS Bilateral adrenal haemorrhage in a critically ill patient Christian M Girgis, Louise Cole and Bernard L Champion Clinical record ABSTRACT A 67-year-old woman presented to the emergency depart- Although rare, bilateral adrenal haemorrhage remains a life- ment with a 3-week history of lower abdominal pain and fever. threatening complication of severe infection and prolonged Following an abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan, she critical illness. A 67-year-old woman developed acute was Critdiagnosed Care Resusc with diverticulitisISSN: 1441-2772 and a 1pericolic June abscess, for adrenal haemorrhage in the context of severe systemic which2011 she 13 underwent 2 123-124 surgical resection of the inflamed bowel, infection due to diverticulitis and pericolic abscess. The abscess©Crit drainage Care and formation Resusc of a colostomy.2011 Thereafter, she www.jficm.anzca.edu.au/aaccm/journal/publi- prompt recognition and management of this condition was was cations.htmtransferred to the intensive care unit, where she received an important component of her eventual recovery. inotropicCase andreports ventilatory support over 2 days for the treatment of severe septic shock (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Crit Care Resusc 2011; 13: 123–124 Evaluation [APACHE] II and Sequential Organ Failure Assess- ment [SOFA] scores, 24 and 7, respectively). The patient made a complete recovery from her critical One day after extubation and cessation of inotropic agents, illness, but her adrenal insufficiency persisted as demon- she became acutely ill with hypotension (blood pressure, 90/ strated by a significantly low baseline cortisol level (90 nmol/ 60mmHg), delirium, hyponatraemia and hyperkalaemia L) 1 month after the initial diagnosis and persistent changes (sodium [Na+], 130mmol/L, reference range [RR], 135– to suggest adrenal haemorrhage on magnetic resonance 145mmol/L; potassium [K+], 5.4mmol/L, RR, 3.5–5.0mmol/L).