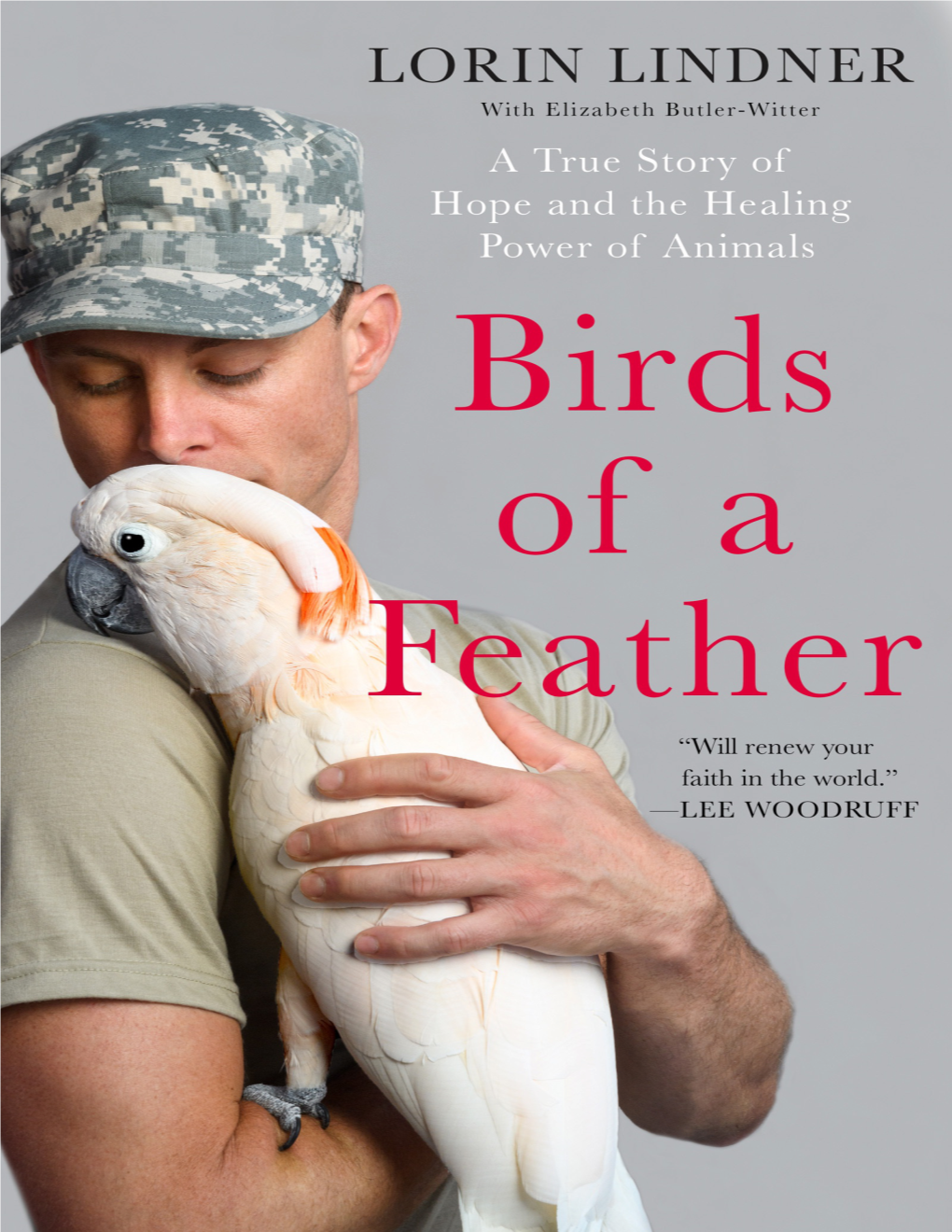

Birds of a Feather

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The People of Leonardo's Basement

The people of 26. Ant, or Anthony Davis 58. Fred Rogers Leonardo’s Basement 27. Slug, or Sean Daley 59. Steve Jevning The people - in popular culture, 28. Tony Sanneh 60. Tracy Nielsen business, politics, engineering, art, and technology - chosen for the 29. Lin-Manuel Miranda 61. Albert Einstein album cover redux have provided 30. Joan (of Art) Mondale 62. Maria Montessori inspiration to Leonardo’s Basement for 20 years. Many have a connection 31. Herbert Sellner 63. Nikola Tesla to Minnesota! 32. H.G. Wells 64. Leonardo da Vinci 1. Richard Dean Anderson, or 33. Rose Totino 65. Neal deGrasse Tyson MacGyver 34. Heidemarie Stefanyshyn- 66. John Dewey 2. Kofi Annan Piper 67. Frances McDormand or 3. Dave Arneson 35. Louie Anderson Marge Gunderson 4. Earl Bakken 36. Jeannette Piccard 68. Rocket girl 5. Ann Bancroft 37. Barry Kudrowitz 69. Ada Lovelace 6. Clyde Bellecourt 38. Jane Russell 70. Mary Tyler Moore or Mary Richards 7. Leeann Chin 39. Winona Ryder 71. Newton’s Apple 8. Judy Garland 40. June Marlowe 72. Wendell Anderson 9. Terry Lewis 41. Gordon Parks 73. Ralph Samuelson 10. Jimmy Jam 42. August Wilson 74. Jessica Lange 11. Kate DiCamillo 43. Rebecca Schatz 75. Trojan Horse 12. Dessa, or Margret Wander 44. Fred Rose 76. TARDIS 13. Walter Deubner 45. Cheryl Moeller 77. Cardboard castle 14. Reyn Guyer 46. Paul Bunyan 78. Millennium Falcon 15. Bob Dylan (Another Side of) 47. Mona Lisa 79. Chicken 16. Louise Erdich 48. Rocket J. "Rocky" Squirrel 80. Drum head, inspired by 17. Peter Docter 49. Bullwinkle J. -

Bob Barker Farm to Fridge to the Rescue New Film Serves TV Legend Comes to Food for Thought the Aid of Calves Confronting Cafos Exclusive Interview with Dan Imhoff

- FREE - Go ahead, take it. Living Compassionate CTHE MAG OF MFA. SPRING-SUMMERL 11 ISSUE 8 Fishy Business MFA Goes Undercover at a Fish Slaughter Facility Bob Barker Farm to Fridge to the Rescue New Film Serves TV Legend Comes to Food for Thought the Aid of Calves Confronting CAFOs Exclusive Interview with Dan Imhoff MercyForAnimals.org dear friends newswatch Living Mark Bittman, columnist for The New York Times, recently wrote that “organizations like the Humane Society and Mercy For Animals need to be allowed to Heart-Healthy Vegetarian Diets Save Lives do the work that the federal and state governments Compassionate In February 2010, an article in Reuters warned that heart Luckily, this year, a new documentary has brought are not: documenting the kind of behavior most of us disease, caused primarily by excess meat consumption, this important message to the masses. Recounting the abhor. Indeed, the independent investigators should CL would kill 400,000 Americans that year. Researchers have journeys of Dr. Caldwell Esselstyn, known for successfully be supported.” Contributors been warning Americans for years that meaty diets are bad reversing heart disease through diet, and Dr. Colin Amy Bradley for the heart and that well-planned, plant-based diets help T. Campbell, author of The China Study, the most I couldn’t agree more. In fact, most people feel the Derek Coons protect against heart disease. In fact, William Castelli, M.D., comprehensive study of nutrition ever conducted, same. A recent poll on the effort in Iowa to criminalize Forks Over Knives aims to save lives by showing Eddie Garza director of the Framingham Heart Study, the longest- undercover animal cruelty investigations found that running clinical study in medical history, says heart disease heart disease and other deadly diseases “can be Daniel Hauff a mere 21 percent of respondents supported the bills. -

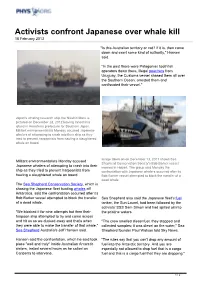

Activists Confront Japanese Over Whale Kill 18 February 2013

Activists confront Japanese over whale kill 18 February 2013 "Is this Australian territory or not? If it is, then come down and exert some kind of authority," Hansen said. "In the past there were Patagonian toothfish operators down there, illegal poachers from Uruguay, the Customs vessel chased them all over the Southern Ocean, arrested them and confiscated their vessel." Japan's whaling research ship the Nisshin Maru is pictured on December 28, 2012 leaving Innoshima island in Hiroshima prefecture for Southern Japan. Militant environmentalists Monday accused Japanese whalers of attempting to crash into their ship as they tried to prevent harpoonists from hauling a slaughtered whale on board. Image taken on on December 13, 2011 shows Sea Militant environmentalists Monday accused Shepherd Conservation Society's Bob Barker vessel Japanese whalers of attempting to crash into their moored in Hobart. The group said Monday the ship as they tried to prevent harpoonists from confrontation with Japanese whalers occurred after its hauling a slaughtered whale on board. Bob Barker vessel attempted to block the transfer of a dead whale. The Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, which is chasing the Japanese fleet hunting whales off Antarctica, said the confrontation occurred after its Bob Barker vessel attempted to block the transfer Sea Shepherd also said the Japanese fleet's fuel of a dead whale. tanker, the Sun Laurel, had been followed by the activists' SSS Sam Simon and had spilled oil into "We blocked it for nine attempts but then their the pristine waters. harpoon ship attempted to try and come across and hit us so we ducked away and that's when "The crew smelled diesel fuel, they stopped and they were able to make the transfer of that whale," collected samples; it was diesel on the water," Sea Sea Shepherd Australia's Jeff Hansen said. -

Bob Barker Has Made a Huge Impact on Television, and on Animal Rights, Too

2015 LEGEND AWARD A Host and a Legend BOB BARKER HAS MADE A HUGE IMPACT ON TELEVISION, AND ON ANIMAL RIGHTS, TOO BY PATT f there were a Mt. Rushmore for television this name; you’re going to hear a lot about him.” When he landed as host MORRISON game show hosts, there’s no doubt about it: Bob Barker, for his part, said modestly that, “I feel like Barker would be up there. I’m hitting afer Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig.” on “The Price is Right” Even without being made of granite, his face Barker went on to become a one-man Murderers’ has endured, flling Americans’ eyeballs and Row of game show hosts, making a long-lasting mark in 1972, he found his television screens for a remarkable half-century. He on “Truth or Consequences” and hosting a number of Ihelped to defne the game-show genre, as a pioneer in others that came and went. television home, the myriad ways, right down to taking the radical step of But when he landed as host on “Te Price is Right” letting his hair go naturally white for TV. He has nearly in 1972, he found his television home, the place where place where he broke 20 Emmys to his credit. he broke Johnny Carson’s 29-year record as longest- Johnny Carson’s 29-year Now, he is the recipient of the Legend Award from serving host of a TV show. the Los Angeles Press Club, presented at the 2015 It’s easy to rattle of numbers—for example, the frst record as longest-serving National Arts & Entertainment Awards. -

Top Singles TéLã©Chargã©S (01/03/2019

Top Albums (06/09/2019 - 13/09/2019) Pos. SD Artiste Titre Éditeur Distributeur 1 NISKA MR SAL CAPITOL MUSIC FRANCE UNIVERSAL MUSIC FRANCE 2 1 JEAN-BAPTISTE GUEGAN PUISQUE C'EST ÉCRIT SMART SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT 3 2 VITAA & SLIMANE VERSUS MERCURY MUSIC GROUP UNIVERSAL MUSIC FRANCE 4 3 NEKFEU LES ÉTOILES VAGABONDES : EXPANSION SEINE ZOO RECORDS UNIVERSAL MUSIC FRANCE 5 YANNICK NOAH BONHEUR INDIGO COLUMBIA SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT 6 7 ANGÈLE BROL INITIAL ARTIST SERVICES UNIVERSAL MUSIC FRANCE 7 5 LORENZO SEX IN THE CITY INITIAL ARTIST SERVICES UNIVERSAL MUSIC FRANCE 8 8 NINHO DESTIN REC. 118 / MAL LUNE MUSIC WARNER MUSIC FRANCE 9 10 SOPRANO PHOENIX REC. 118 WARNER MUSIC FRANCE 10 11 PNL DEUX FRERES BELIEVE BELIEVE 11 POST MALONE HOLLYWOOD'S BLEEDING DEF JAM RECORDINGS FRANCE 12 13 JUL RIEN 100 RIEN BELIEVE BELIEVE 13 12 EVA QUEEN MCA UNIVERSAL MUSIC FRANCE 14 16 MAÎTRE GIMS CEINTURE NOIRE SONY MUSIC DISTRIBUES SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT 15 4 LANA DEL REY NORMAN FUCKING ROCKWELL! POLYDOR UNIVERSAL MUSIC FRANCE 16 18 TROIS CAFES GOURMANDS UN AIR DE RIEN PLAY TWO WARNER MUSIC FRANCE 17 OXMO PUCCINO LA NUIT DU REVEIL BELIEVE BELIEVE 18 IGGY POP FREE CAROLINE FRANCE UNIVERSAL MUSIC FRANCE 19 6 RILÈS WELCOME TO THE JUNGLE CAPITOL MUSIC FRANCE UNIVERSAL MUSIC FRANCE 20 14 AYA NAKAMURA NAKAMURA REC. 118 WARNER MUSIC FRANCE 21 15 ELSA ESNOULT 4 JLA PRODUCTIONS WAGRAM 22 17 NAPS ON EST FAIT POUR CA BELIEVE BELIEVE 23 19 LADY GAGA A STAR IS BORN SOUNDTRACK POLYDOR UNIVERSAL MUSIC FRANCE 24 20 ED SHEERAN NO.6 COLLABORATIONS PROJECT WEA WARNER MUSIC FRANCE 25 22 M. -

Hitchcock's Appetites

McKittrick, Casey. "Epilogue." Hitchcock’s Appetites: The corpulent plots of desire and dread. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. 159–163. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 28 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501311642.0011>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 28 September 2021, 08:18 UTC. Copyright © Casey McKittrick 2016. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. Epilogue itchcock and his works continue to experience life among generation Y Hand beyond, though it is admittedly disconcerting to walk into an undergraduate lecture hall and see few, if any, lights go on at the mention of his name. Disconcerting as it may be, all ill feelings are forgotten when I watch an auditorium of eighteen- to twenty-one-year-olds transported by the emotions, the humor, and the compulsions of his cinema. But certainly the college classroom is not the only guardian of Hitchcock ’ s fl ame. His fi lms still play at retrospectives, in fi lm festivals, in the rising number of fi lm studies classes in high schools, on Turner Classic Movies, and other networks devoted to the “ oldies. ” The wonderful Bates Motel has emerged as a TV serial prequel to Psycho , illustrating the formative years of Norman Bates; it will see a second season in the coming months. Alfred Hitchcock Presents and The Alfred Hitchcock Hour are still in strong syndication. Both his fi lms and television shows do very well in collections and singly on Amazon and other e-commerce sites. -

MCA-500 Reissue Series

MCA 500 Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan MCA-500 Reissue Series: MCA 500 - Uncle Pen - Bill Monroe [1974] Reissue of Decca DL 7 5348. Jenny Lynn/Methodist Preacher/Goin' Up Caney/Dead March/Lee Weddin Tune/Poor White Folks//Candy Gal/Texas Gallop/Old Grey Mare Came Tearing Out Of The Wilderness/Heel And Toe Polka/Kiss Me Waltz MCA 501 - Sincerely - Kitty Wells [1974] Reissue of Decca DL 7 5350. Sincerely/All His Children/Bedtime Story/Reno Airport- Nashville Plane/A Bridge I Just Can't Burn/Love Is The Answer//My Hang Up Is You/Just For What I Am/It's Four In The Morning/Everybody's Reaching Out For Someone/J.J. Sneed MCA 502 - Bobby & Sonny - Osborne Brothers [1974] Reissue of Decca DL 7 5356. Today I Started Loving You Again/Ballad Of Forty Dollars/Stand Beside Me, Behind Me/Wash My Face In The Morning/Windy City/Eight More Miles To Louisville//Fireball Mail/Knoxville Girl/I Wonder Why You Said Goodbye/Arkansas/Love's Gonna Live Here MCA 503 - Love Me - Jeannie Pruett [1974] Reissue of Decca DL 7 5360. Love Me/Hold To My Unchanging Love/Call On Me/Lost Forever In Your Kiss/Darlin'/The Happiest Girl In The Whole U.S.A.//To Get To You/My Eyes Could Only See As Far As You/Stay On His Mind/I Forgot More Than You'll Ever Know (About Her)/Nothin' But The Love You Give Me MCA 504 - Where is the Love? - Lenny Dee [1974] Reissue of Decca DL 7 5366. -

Bob Barker Farm to Fridge to the Rescue New Film Serves TV Legend Comes to Food for Thought the Aid of Calves Confronting Cafos Exclusive Interview with Dan Imhoff

- FREE - Go ahead, take it. Living Compassionate CTHE MAG OF MFA. SPRING-SUMMERL 11 ISSUE 8 Fishy Business MFA Goes Undercover at a Fish Slaughter Facility Bob Barker Farm to Fridge to the Rescue New Film Serves TV Legend Comes to Food for Thought the Aid of Calves Confronting CAFOs Exclusive Interview with Dan Imhoff MercyForAnimals.org dear friends Living Mark Bittman, columnist for The New York Times, recently wrote that “organizations like the Humane Society and Mercy For Animals need to be allowed to do the work that the federal and state governments Compassionate are not: documenting the kind of behavior most of us abhor. Indeed, the independent investigators should CL be supported.” Contributors Amy Bradley I couldn’t agree more. In fact, most people feel the Derek Coons same. A recent poll on the effort in Iowa to criminalize Eddie Garza undercover animal cruelty investigations found that Daniel Hauff a mere 21 percent of respondents supported the bills. Arathi Jayaram Another testament to just how out of step agribusiness Brooke Mays has become with mainstream values. Kevin Olliff In addition to shielding animal exploiters from public Matt Rice scrutiny, these bills are a blatant violation of free speech Nathan Runkle and freedom of the press. So much so that the ACLU is Anya Todd actively opposing them. The bills aim to keep consumers Kenny Torrella in the dark, which in turn threatens public health and Cover photo courtesy of CBS. food safety. Remember – the largest beef recall in U.S. Dear Friends, history was the direct result of an undercover cruelty investigation, which exposed “downer” cows – those Factory farming is an ugly business. -

Rising Loaves Anthology 2019 0.Pdf

Cover Art by: Magory Collado "Lawrence Student Writing Workshop: The Rising Loaves” is hosted by the Lawrence History Center, developed in collaboration with Andover Bread Loaf, and funded in part by the Catherine McCarthy Trust, the Essex County Community Foundation Greater Lawrence Summer Fund, W. Dean and Sy Eastman, the Pringle Foundation, the Stearns and Russell Trusts, Rogers Family Foundation, Andover Bread Loaf, and the Lawrence Public School lunch program. A Letter from the Program Directors …….………………...…….………………..3 Student and Writing Leader Work Brianna Anderson ………………………………….……....……..………..……5 Jhandaries Ayala ………………………………….……....…………...…...……5 Sheila Barry ………………………………….……....……………..……………6 Angelique Ceballos Cardona ………………………………….…….………..…6 Magory Collado ………………………………….……....………………………7 Kelley De Leon ………………………………….……....……….………………8 Michael De Leon ………………………………….……....………..……………9 Isabella Delgado ………………………………….……....…………..………...10 Jennifer Escalante ………………………………….……....………..…………10 Julien Felipe ………………………………….……....………………………….11 Angell Flores …………………………………………………….………..…..…11 Anelyn Gomez ………………………………….……........…….………………12 Karen Gonzalez ………………………………….………....…….……..………12 Katarina Guerrero ………………………………….……........………..………12 Mary Guerrero ………………………………………………..….……..………13 Lee Krishnan ………………………………….……....…………….……..……13 Breison Lopez ………………………………….……....……………….………14 Edin Macario ………………………………….……....………………..….……14 Manuel Maurico ………………………………….……....…………..…………15 Mekhi Mendoza ………………………………….……....…………..…………15 Jennifer Merida ………………………………….……....……………………...15 -

It Must Be Karma: the Story of Vicki Joy and Johnnymoon

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-14-2010 It Must be Karma: The Story of Vicki Joy and Johnnymoon Richard Bolner University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Bolner, Richard, "It Must be Karma: The Story of Vicki Joy and Johnnymoon" (2010). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 1121. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/1121 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. It Must be Karma: The Story of Vicki Joy and Johnnymoon A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Fine Arts in Film, Theatre and Communication Arts Creative Writing by Rick Bolner B.S. University of New Orleans, 1982 May, 2010 Table of Contents Prologue ...............................................................................................................................1 -

Hazleton Archery Club 3D Course Open to the Public

Serving Carbon, Columbia, luzerne, monroe & SCHuYlKill CountieS E H T PROGRESS Neighborhood Happenings & Events Magazine June 2019 • Volume 6 • Issue 6 Hazleton Archery Club F R E E 3D Course Promoting Local Open to the Public Small Businesses FRANK BALON/for The Progress Magazine & Events at an Hazleton Archery Club at 162 Woodside course, we offer a 60 yard bonus shot at a bull Affordable Price Drive, Freeland is now open to the public. The 3D moose. Fees for Club Members and Non-Members course is newly designed and features 20 are as follows: In - challenging targets from varying distances in a 3D PASS FEES Members are $25 for a single • Albrightsville beautiful wooded setting on the Archery Club's member and $35 for member family. Non-Member Property. All paths are clearing marked and all PASS FEE at $50 for single and $60 for non-mem - • Bear Creek targets have shooting lines for both Compound ber family. Daily Use FEE will be $5 Member and • Beaver Meadows and Advanced Archers as well as closer lines for $10 Non-Member. Kids under age 16 shoot for • Berwick Youth and Traditional Archers. Target distances FREE. To purchase a 3D Pass contact the Club range from 10 yards to 45 yards with the majority Treasurer at 570-926-7681 or visit the Hazleton • Blakeslee in the 15 to 30 yard range. At the end of the Archery Club on Facebook and leave a Message. • Conyngham • Drums • Freeland • Hazleton • Hometown • Jim Thorpe • Lake Harmony • Lehighton • Long Pond • McAdoo • Mountaintop • Mount Pocono • Nescopeck • Pocono Pines • Sugarloaf Forgotten Warriors Motorcycle Run • Tamaqua P • Tresckow In Memory of Bob “Cowboy” Hludzik • Weatherly SATURDAY, JULY 13th, 2019 • West Hazleton • White Haven See back cover for details! THE PROGRESS MAGAZINE PAGE 1 To submit an article/event/ad/photo e to “The Progress” please contact h PROGRESS T Shari Roberts Neighborhood Happenings & Events Magazine Editor/Publisher/Sales .................................(570) 401-1798 [email protected] Letter from the Editor Regina R. -

OVERVIEW of Who Is Big Cat Rescue?

Big Cat Rescue in Tampa Florida Who Is Big Cat Rescue 1 Table Of Contents Chapter 2 - Who Is Big Cat Rescue Chapter 3 - Non-Profit Ratings Chapter 4 - Award Winning Sanctuary Chapter 5 - Cable Television Segments Chapter 6 - Celebrity Supporters Chapter 7 - Area Business Affiliations Chapter 8 - How Big Cat Rescue Started Chapter 9 - The History & Evolution of Big Cat Rescue Chapter 10 - Cat Links 1 2 Who Is Big Cat Rescue OVERVIEW of Who is Big Cat Rescue? Big Cat Rescue is the largest accredited sanctu- ary in the world dedicated entirely to abused and abandoned big cats. We are home to over 100 lions, tigers, bobcats, cougars and other species most of whom have been abandoned, abused, orphaned, saved from being turned into fur coats, or retired from performing acts. Our dual mission is to provide the best home we can for the cats in our care and educate the pub- lic about the plight of these majestic animals, both in captivity and in the wild, to end abuse and avoid extinction. The sanctuary began in 1992 when the Founder, Carole Baskin, and her then husband Don, mistakenly believing that bobcats made good pets, went looking to buy some kit- tens. They inadvertently ended up at a “fur farm” and bought all 56 kittens to keep them from being turned into fur coats. See How We Started. In the early years, influenced by breeders and pet owners, they believed that the cats made suitable pets and that breeding and placing the cats in homes was a way to “pre- serve the species.” Gradually they saw increasing evidence that not only was this not the case, but that it was leading to a consistent pattern of suffering and abuse.