The Net Result: Social Inclusion in the Information Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Benchmarking of Australian Telecommunications International Services Benchmarking

telecoms.qxd 9/03/99 10:06 AM Page 1 International Benchmarking of Australian Telecommunications International Services Benchmarking March 1999 Commonwealth of Australia 1999 ISBN 0 646 33589 8 This work is subject to copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, the work may be reproduced in whole or in part for study or training purposes, subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgment of the source. Reproduction for commercial use or sale requires prior written permission from AusInfo. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Manager, Legislative Services, AusInfo, GPO Box 1920, Canberra, ACT, 2601. Inquiries: Media and Publications Productivity Commission Locked Bag 2 Collins Street East Post Office Melbourne Vic 8003 Tel: (03) 9653 2244 Fax: (03) 9653 2303 Email: [email protected] An appropriate citation for this paper is: Productivity Commission 1999, International Benchmarking of Australian Telecommunications Services, Research Report, AusInfo, Melbourne, March. The Productivity Commission The Productivity Commission, an independent Commonwealth agency, is the Government’s principal review and advisory body on microeconomic policy and regulation. It conducts public inquiries and research into a broad range of economic and social issues affecting the welfare of Australians. The Commission’s independence is underpinned by an Act of Parliament. Its processes and outputs are open to public scrutiny and are driven by concern for the wellbeing of the community as a whole. Information on the Productivity Commission, its publications and its current work program can be found on the World Wide Web at www.pc.gov.au or by contacting Media and Publications on (03) 9653 2244. -

APPENDICES to the Evidence of Michael Piaskoski Rogers Communications Partnership

EB-2015-0141 Ontario Energy Board IN THE MATTER OF the Ontario Energy Board Act, 1998, S.O. 1998, c.15, (Schedule B); AND IN THE MATTER OF Decision EB-2013-0416/EB- 2014-0247 of the Ontario Energy Board (the “OEB”) issued March 12, 2015 approving distribution rates and charges for Hydro One Networks Inc. (“Hydro One”) for 2015 through 2017, including an increase to the Pole Access Charge; AND IN THE MATTER OF the Decision of the OEB issued April 17, 2015 setting the Pole Access Charge as interim rather than final; AND IN THE MATTER OF the Decision and Order issued June 30, 2015 by the OEB granting party status to Rogers Communications Partnership, Allstream Inc., Shaw Communications Inc., Cogeco Cable Inc., on behalf of itself and its affiliate, Cogeco Cable Canada LP, Quebecor Media, Bragg Communications, Packet-tel Corp., Niagara Regional Broadband Network, Tbaytel, Independent Telecommunications Providers Association (ITPA) and Canadian Cable Systems Alliance Inc. (CCSA) (collectively, the “Carriers”); AND IN THE MATTER OF Procedural Order No. 4 of the OEB issued October 26, 2015 setting dates for, inter alia, evidence of the Carriers. APPENDICES to the Evidence of Michael Piaskoski Rogers Communications Partnership November 20, 2015 EB-2015-0141 APPENDIX A to the Evidence of Michael Piaskoski Rogers Communications Partnership November 20, 2015 Michael E. Piaskoski SUMMARY OF QUALIFICATIONS Eight years in Rogers Regulatory proceeded by 12 years as a telecom lawyer specializing in regulatory, competition and commercial matters. Bright, professional and ambitious performer who continually exceeds expectations. Expertise in drafting cogent, concise and easy-to-understand regulatory and legal filings and litigation materials. -

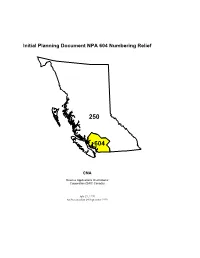

Initial Planning Document NPA 604 Numbering Relief

Initial Planning Document NPA 604 Numbering Relief 250 604 CNA Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC Canada) July 27, 1999 As Presented on 24 September 1999 INITIAL PLANNING DOCUMENT NPA 604 NUMBERING RELIEF JULY 27, 1999 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................... 1 2. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 1 3. CENTRAL OFFICE CODE EXHAUST .................................................................................................... 2 4. CODE RELIEF METHODS...................................................................................................................... 3 4.1. Geographic Split.............................................................................................................................. 3 4.1.1. Definition ...................................................................................................................................... 3 4.1.2. General Attributes ........................................................................................................................ 4 4.2. Distributed Overlay .......................................................................................................................... 4 4.2.1. Definition ..................................................................................................................................... -

PART a Definitions and General Terms 5 ITEM 100

iTeraTEL Communications CRTC 15190 ACCESS SERVICES TARIFF Original Title Page ACCESS SERVICES TARIFF This Tariff sets out the rates, terms and conditions applicable to the interconnection arrangements provisioned to providers of telecommunications services and facilities. Issue Date: December 2,2019 Effective Date: January 15, 2015 Tariff Notice 1 iTeraTEL Communications Inc. CRTC 15190 ACCESS SERVICES TARIFF Original Page 1 Explanation of Symbols The following symbols are used in this Tariff and have meanings as shown: A Increase in rate or charge C Change in wording D Discontinued rate or regulation F Reformatting of existing material with no change to rate or charge M Matter moved from its previous location N New wording, rate or charge R Reduction in rate or charge S Reissued matter Abbreviations of Companies Names The following companies names are used in this Tariff and have meanings as shown: Aliant Aliant Telecom Inc. Bell Bell Canada Bell Aliant Bell Aliant Regional Communications, Limited Partnership IslandTel Island Telecom Inc. MTS MTS Allstream Inc. MTT Maritime Tel & Tel Limited NBTel NBTel NewTel NewTel Communications NorthernTel NorthernTel, Limited Partnership SaskTel SaskTel TBayTel TBayTel TCBC TELUS Communications Company, operating in British Columbia TCC TELUS Communications Company TCI TELUS Communications Company, operating in Alberta TCQ TELUS Communications Company, operating in Quebec Télébec Télébec, société en commandite Issue Date: December 2,2019 Effective Date: January 15, 2015 Tariff Notice 1 iTeraTEL Communications Inc. CRTC 15190 ACCESS SERVICES TARIFF Original Page 2 Check Page Issue Date: December 2, 2019 Effective Date: January 15, 2020 Tariff Notice 1 iTeraTEL Communications Inc. CRTC 15190 ACCESS SERVICES TARIFF Original Page 3 Table of Contents Page Explanation of Symbols 1 Abbreviations of Companies Names 1 Check Page 2 Table of Contents 3 PART A Definitions and General Terms 5 ITEM 100. -

49807 Bell AIF Eng Clean

BELL CANADA ANNUAL INFORMATION FORM FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2001 APRIL 15, 2002 2001 T ABLE OF CONTENTS Annual Information Form for the year ended December 31, 2001 April 15, 2002 Documents Incorporated by Reference . .1 Documents incorporated by reference Part of Annual Information Form in Trade-marks . .1 Document which incorporated by reference Item 1 • Corporate Structure of Bell Canada . .2 Portions of the 2001 Bell Canada Financial Information Item 5 Item 2 • General Development of Bell Canada . .2 Item 3 • Business of Bell Canada . .3 General . .3 Principal Service Area . .5 Subsidiaries and Associated Companies . .5 Regulation . .8 Competition . .12 Capital Expenditures . .15 Environment . .15 Employee Relations . .16 Legal Proceedings . .16 Trade-marks Certain Contracts . .17 Owner Trade-mark Forward-Looking Statements . .18 Bell Canada Rings & Head Design Risk Factors . .18 (Bell Canada corporate logo) Bell Item 4 • Selected Financial Information (Consolidated) . .20 Bell World Item 5 • Management’s Discussion and Analysis . .21 Espace Bell Sympatico Item 6 • Market for the Securities of Bell Canada . .21 Bell ActiMedia Inc. Yellow Pages Item 7 • Directors and Officers of Bell Canada . .21 Bell Mobility Inc. / Bell Mobilité inc. Mobile Browser Item 8 • Additional Information . .23 Manitoba Telecom Services Inc. First Rate Schedule – Directors’ and Officers’ Remuneration . .24 Stentor Resource Centre Inc. / Datapac Centre de ressources Stentor Inc. Megalink SmartTouch AT&T Corp. AT&T MCI Communications Corporation Hyperstream OnStar Corporation Onstar NOTES: (1) Unless the context indicates otherwise, “Bell Canada” refers to Bell Canada and its subsidiaries Yahoo! Inc. Yahoo! and associated companies. (2) All dollar figures are in Canadian dollars, unless otherwise indicated. -

Visions of Electric Media Electric of Visions

TELEVISUAL CULTURE Roberts Visions of Electric Media Ivy Roberts Visions of Electric Media Television in the Victorian and Machine Ages Visions of Electric Media Televisual Culture Televisual culture encompasses and crosses all aspects of television – past, current and future – from its experiential dimensions to its aesthetic strategies, from its technological developments to its crossmedial extensions. The ‘televisual’ names a condition of transformation that is altering the coordinates through which we understand, theorize, intervene, and challenge contemporary media culture. Shifts in production practices, consumption circuits, technologies of distribution and access, and the aesthetic qualities of televisual texts foreground the dynamic place of television in the contemporary media landscape. They demand that we revisit concepts such as liveness, media event, audiences and broadcasting, but also that we theorize new concepts to meet the rapidly changing conditions of the televisual. The series aims at seriously analyzing both the contemporary specificity of the televisual and the challenges uncovered by new developments in technology and theory in an age in which digitization and convergence are redrawing the boundaries of media. Series editors Sudeep Dasgupta, Joke Hermes, Misha Kavka, Jaap Kooijman, Markus Stauff Visions of Electric Media Television in the Victorian and Machine Ages Ivy Roberts Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: ‘Professor Goaheadison’s Latest,’ Fun, 3 July 1889, 6. Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden -

Y Bwletin Gwasg Y Nant – Valley Press Mis Medi 2004 – September 2004

Y Bwletin Gwasg y Nant – Valley Press Mis Medi 2004 – September 2004 Llywydd - President Glenson T. Jones Email: [email protected] 51 McIntosh Place Kanata ON K2L 2N7 (613) 592-8957 Fax: (613) 592-8635 Ysgrifennydd - Secretary Kimberly Power Email: [email protected] 17 Trotting Way Kanata ON K2M 1B3 Phone: (613) 592-5795 Website: http://www.ottawawelshsociety.com/ - Out of service at the moment Cynnwys - Contents Faggots & Peas Noson Lawen, Saturday November 13th Page 1 – Upcoming Events, Notices, Picnic Westminster Presbyterian Church 470 Roosevelt Avenue. Page 2 –Seven Wonders, Poetry Doors open at 6:30pm with dinner at 7:00 pm. Cost is $12.00 per adult and $5.00 for children. Cash bar available. Page 3 – Welsh Workers, Welsh Course, Local News Page 4 – North American Festival, Bog Snorkelling Reserve meal by calling Rhian at 828-4579 or e-mail [email protected] Digwyddiadau - Events for 2004-2005 Welsh Film Night Tues. Oct 19 CALLING ALL TALENT!! Noson Lawen / Faggots & Peas Sat. Nov. 13 If you have an act yourself, or a talented child Ottawa Welsh Choral Society Sat. Nov 27 (as I know many of you DO) Children’s Christmas Party – call Kim for information Dec. please volunteer to perform at the Nosen Lawen on Christmas Carol Service Sun. Dec 19 November 13th English Film Night tentatively Jan or Mar (don’t worry, it is a Saturday!). St. David’s Day Banquet & Dance Sat. Feb 26 Gymanfa Ganu Sun. Feb. 27 Call me at 733-6066, or email at Pot Luck & Annual meeting April or May [email protected] Noson Ffilm Gymraeg or even call work at 520-2600, ext 3614. -

Trafalgar Square Publishing Spring 2016 Don’T Miss Contents

Trafalgar Square Publishing Spring 2016 Don’t Miss Contents Animals/Pets .....................................................................120, 122–124, 134–135 28 Planting Design Architecture .................................................................................... 4–7, 173–174 for Dry Gardens Art .......................................................8–9, 10, 12, 18, 25–26 132, 153, 278, 288 Autobiography/Biography ..............37–38, 41, 105–106, 108–113, 124, 162–169, 179–181, 183, 186, 191, 198, 214, 216, 218, 253, 258–259, 261, 263–264, 267, 289, 304 Body, Mind, Spirit ....................................................................................... 33–34 Business ................................................................................................... 254–256 Classics ....................................................................................43–45, 47–48, 292 Cooking ......................................................1, 11, 14–15, 222–227, 229–230–248 Crafts & Hobbies .............................................................................21–24, 26–27 85 The Looking Design ......................................................................................................... 19–20 Glass House Erotica .................................................................................................... 102–103 Essays .............................................................................................................. 292 Fiction ...............................................42, -

Nick Dusic 1978

The BulletinYOUR MAGAZINE FROM THE BRITISH ECOLOGICAL SOCIETY inFOCUS Photo: Frazer Bird The BES Roadies hit the Wychwood Festival n June. Will Gosling helps budding ecologists match the poo to the animal. Contents August 2013 OFFICERS AND COUNCIL FOR THE YEAR 2012-3 REGULARS President: Georgina Mace Welcome / Alan Crowden 4 President Elect: Bill Sutherland Vice-Presidents: Richard Bardgett, President’s Piece / Georgina Mace 6 Mick Crawley Honorary Treasurer: Drew Purves Ecology Education and Careers / Karen Devine and Olivia Richardson 18 Council Secretary: Dave Hodgson Honorary Chairpersons: Science Policy 20 Andrew Beckerman (Meetings) Alan Gray (Publications) Special Interest Group News 23 Lesley Batty (Education, Training and Careers) The Chartered Institute of Ecology and Environmental Management / Sally Hayns 44 Juliet Vickery (Public and Policy) Richard Bardgett (Grants) Rant and Reason / Markus Eichhorn 46 ORDINARY MEMBERS Publishing News 48 OF COUNCIL: Retiring David Coomes, Thomas Ezard, 2013 Book Reviews 52 Rosemary Hails Diary 60 Emma Goldberg, 2014 William Gosling, Ruth Mitchell Julia Blanchard, 2015 Greg Hurst, Paul Raven FEATURES Emma Sayer, Owen Lewis, 2016 Science Policy Special Event / Martin Smith 8 Matt O’Callaghan Bulletin Editor: Alan Crowden INTECOL 2013 15 48 Thornton Close, Girton, Cambridge CB3 0NG Sun, Fun and Ecology / The BES Roadies 12 Tel: 07801 068458 Email: Nick Dusic 1978-2013 22 [email protected] The Quiet Places / Rose Hanley-Nickolls 28 Associate Editor: Emma Sayer Department of -

Spectrum Maanagement in Australia

SPECTRUM MANAGEMENT FOR A CONVERGING WORLD: CASE STUDY ON AUSTRALIA International Telecommunication Union Spectrum Management for a Converging World: Case Study on Australia This case study has been prepared by Fabio Leite <[email protected]>, Counsellor, Radiocommunication Bureau, ITU as part of a Workshop on Radio Spectrum Management for a Converging World jointly produced under the New Initiatives programme of the Office of the Secretary General and the Radiocommunication Bureau. The workshop manager is Eric Lie <[email protected]>, and the series is organized under the overall responsibility of Tim Kelly <[email protected]>, Head, ITU Strategy and Policy Unit (SPU). Other case studies on spectrum management in the United Kingdom and Guatemala can be found at: http://www.itu.int/osg/sec/spu/ni/fmi/case_studies/. This report has benefited from the input and comments of many people to whom the author owes his sincere thanks. In particular, I would like to thank Colin Langtry, my Australian colleague in the Radiocommunication Bureau, for his invaluable comments and explanations, as well as for his placid tolerance of my modestly evolving knowledge of his country. I would also like to express my gratitude to all officials and representatives whom I visited in Australia and who assisted me in preparing this case study, particularly to those of the Australian Communications Authority for their availability in providing support, explanations, comments, and documentation, which made up this report. Above all, I am grateful to those who were kind enough to accept this report as a succinct but fair description of the spectrum management framework in Australia. -

Privateline Magazine-November-December-1995.Pdf

Volume 2, No. 6 Nov ember/December $4.50 rivate line a journal of inquiry into the telephone system Alexander Graham Bell CABLE STATION ... OPERATIONS J • > , t f CANADIAN i TELECOM, - PART2 DIGITAL TELEPHONY BILL UPDATE MICROWAVE PROPAGATION BASICS DEF CON Ill REVIEW INDEX TO PR/VA TE LINE, VOLUME2 As reported oo CBS "60 Mlnu111•: How cortaln de vices can slowd own - 1v1nslop - watthour mel11I- Damien Thorn's ceLLULAR+co MPUTERS+TELco+sEcuRrrv :!'~:~d:,,~r~~Jro~: :ii~~~/!l!~~~~~:~ scrlbesm eler creep, overload droop, elc. Plans $29. 1,0, MANUAL,Exte rnal maoneUcwa ys (applled lo the melerlts eH)l o slow down and slopwaltllo ur melers 1 ULTIMATE HACKER 2011 Cruc en t Dr ., P.O . Drawer 537 ;l'~Ed~s ~'io~ ~~~~~r ~e~~~s :~~ ~ Alamogordo , NM 8831 o error modes( many), ANSI Standards, etc.Dem and and ~ (5051 439-1776 439 -8551 · Polyphan Melen. E,perlmcntalresulls l o slow and 8A M _ 7PM MST, Mon_ sai stop metersby others. $19. Any 2, $38. All 3, $59. Ell.!G (5051 434-0234, 434 -1778 (orde,s FILE ARCHIVE ON CD-ROM only;W you g el voice,enler• 111 111· anyUme): 24-hr ATMcrlm11 , abuses,,u ln111blllUn and dalHls 11- Fcea Te c h Byooo n; (relates dlrecUy1 0 your posedl1 00+ methodsd eta!ed, Include:Physka l, Reg. orderor prospectiveOfde~: Tu••· and Thurs. only. E. cipher, PINcompromise. card counterteltino, mao lili.lllunJJ tdlltlJl~ ZJ!ll±.AddS5 neticslrlpe, fa lse froo~ TEMrEST, Van Ed<.tapping , 10131s;lffOS: Canada) . Al aemsIn slock. VI SA.M C11dOK. spoollng,Inside lob , •~r-<ool, vfbrallon,pulse, high The entire underground NoCODs °' 'bill me•s.Ne w Catalog (200+ olfersl $2 voltage- olhers.C ase his1<>f1es,law, comlermeasures, order $5'N1! (check or MO).li!l..d.Qlru. -

Telecom Public Notice CRTC 2006-10

Telecom Public Notice CRTC 2006-10 Ottawa, 7 July 2006 Continued need for the regulatory constraints applicable to toll and toll-free services Reference: 8661-C12-200608672 and 8661-B2-200605719 In this Public Notice, the Commission initiates a proceeding and invites comments on discontinuing certain regulatory constraints with respect to the basic toll services of Aliant Telecom Inc., Bell Canada, MTS Allstream Inc., Ontera, Saskatchewan Telecommunications, Société en commandite Télébec, Sogetel inc., and TELUS Communications Company. Application 1. The Commission received an application dated 9 May 2006 by Bell Canada, filed under Part VII of the CRTC Telecommunications Rules of Procedure (Bell Canada's Part VII application), seeking an order discontinuing the application of the regulatory constraints applicable to the company's basic toll schedules in its traditional Ontario and Quebec serving territories. 2. Bell Canada noted that in Forbearance – Regulation of toll services provided by incumbent telephone companies, Telecom Decision CRTC 97-19, 18 December 1997, as amended by Telecom Decision CRTC 97-19-1 dated 9 March 1998 (Decision 97-19), the Commission generally forbore from regulating certain incumbent telephone companies'1 toll and toll-free services, but, pursuant to section 24 of the Telecommunications Act (the Act), made the offering and provision of toll services subject to the basic toll constraints set out below (the basic toll constraints): • these telephone companies were to provide to the Commission, and make publicly available, rate schedules setting out the rates for basic toll service. These schedules were to include the 50 percent discount applicable to calls which originated from, and were billed to, the residence service of a registered certified hearing or speech-impaired Telecommunications Devices for the Deaf (TDD) user.