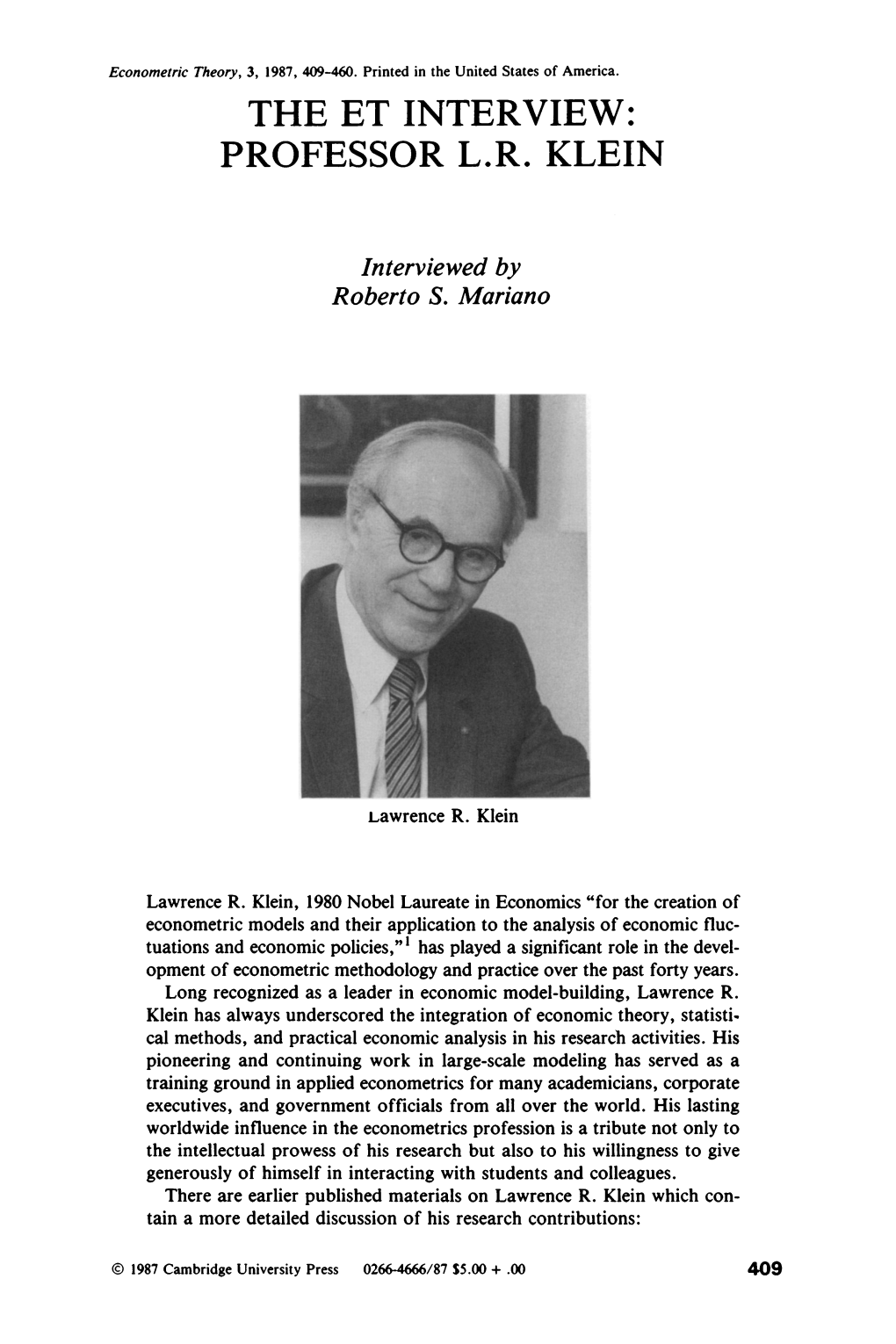

The ET Interview: Professor L. R. Klein

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Influence of Jan Tinbergen on Dutch Economic Policy

De Economist https://doi.org/10.1007/s10645-019-09333-1 The Infuence of Jan Tinbergen on Dutch Economic Policy F. J. H. Don1 © The Author(s) 2019 Abstract From the mid-1920s to the early 1960s, Jan Tinbergen was actively engaged in discussions about Dutch economic policy. He was the frst director of the Central Planning Bureau, from 1945 to 1955. It took quite some time and efort to fnd an efective role for this Bureau vis-à-vis the political decision makers in the REA, a subgroup of the Council of Ministers. Partly as a result of that, Tinbergen’s direct infuence on Dutch (macro)economic policy appears to have been rather small until 1950. In that year two new advisory bodies were established, the Social and Eco- nomic Council (SER) and the Central Economic Committee. Tinbergen was an infuential member of both, which efectively raised his impact on economic pol- icy. In the early ffties he played an important role in shaping the Dutch consen- sus economy. In addition, his indirect infuence has been substantial, as the methods and tools that he developed gained widespread acceptance in the Netherlands and in many other countries. Keywords Consensus economy · Macroeconomic policy · Planning · Policy advice · Tinbergen JEL Classifcation E600 · E610 · N140 The author is a former director of the CPB (1994–2006). He is grateful to Peter van den Berg, André de Jong, Kees van Paridon, Jarig van Sinderen and Bas ter Weel for their comments on earlier drafts. André de Jong also kindly granted access to several documents from his private archive, largely stemming from CPB sources. -

HOW DOES CULTURE MATTER? Amartya Sen 1. Introduction

Forthcoming in "Culture and Public Action" Edited by Vijayendra Rao and Michael Walton. HOW DOES CULTURE MATTER?1 Amartya Sen 1. Introduction Sociologists, anthropologists and historians have often commented on the tendency of economists to pay inadequate attention to culture in investigating the operation of societies in general and the process of development in particular. While we can consider many counterexamples to the alleged neglect of culture by economists, beginning at least with Adam Smith (1776, 1790), John Stuart Mill (1859, 1861), or Alfred Marshall (1891), nevertheless as a general criticism, the charge is, to a considerable extent, justified. This neglect (or perhaps more accurately, comparative indifference) is worth remedying, and economists can fruitfully pay more attention to the influence of culture on economic and social matters. Further, development agencies such as the World Bank may also reflect, at least to some extent, this neglect, if only because they are so predominately influenced by the thinking of economists and financial experts.2 The economists’ scepticism of the role of culture may thus be indirectly reflected in the outlooks and approaches of institutions like the World Bank. No matter how serious this neglect is (and here assessments can differ), the cultural dimension of development requires closer scrutiny in development analysis. It is important to investigate the different ways - and they can be very diverse - in which culture should be taken into account in examining the challenges of development, and in assessing the demands of sound economic strategies. The issue is not whether culture matters, to consider the title of an important and highly successful book jointly edited by Lawrence Harrison and Samuel Huntington.3 That it must be, given the pervasive influence of culture in human life. -

After the Phillips Curve: Persistence of High Inflation and High Unemployment

Conference Series No. 19 BAILY BOSWORTH FAIR FRIEDMAN HELLIWELL KLEIN LUCAS-SARGENT MC NEES MODIGLIANI MOORE MORRIS POOLE SOLOW WACHTER-WACHTER % FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF BOSTON AFTER THE PHILLIPS CURVE: PERSISTENCE OF HIGH INFLATION AND HIGH UNEMPLOYMENT Proceedings of a Conference Held at Edgartown, Massachusetts June 1978 Sponsored by THE FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF BOSTON THE FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF BOSTON CONFERENCE SERIES NO. 1 CONTROLLING MONETARY AGGREGATES JUNE, 1969 NO. 2 THE INTERNATIONAL ADJUSTMENT MECHANISM OCTOBER, 1969 NO. 3 FINANCING STATE and LOCAL GOVERNMENTS in the SEVENTIES JUNE, 1970 NO. 4 HOUSING and MONETARY POLICY OCTOBER, 1970 NO. 5 CONSUMER SPENDING and MONETARY POLICY: THE LINKAGES JUNE, 1971 NO. 6 CANADIAN-UNITED STATES FINANCIAL RELATIONSHIPS SEPTEMBER, 1971 NO. 7 FINANCING PUBLIC SCHOOLS JANUARY, 1972 NO. 8 POLICIES for a MORE COMPETITIVE FINANCIAL SYSTEM JUNE, 1972 NO. 9 CONTROLLING MONETARY AGGREGATES II: the IMPLEMENTATION SEPTEMBER, 1972 NO. 10 ISSUES .in FEDERAL DEBT MANAGEMENT JUNE 1973 NO. 11 CREDIT ALLOCATION TECHNIQUES and MONETARY POLICY SEPBEMBER 1973 NO. 12 INTERNATIONAL ASPECTS of STABILIZATION POLICIES JUNE 1974 NO. 13 THE ECONOMICS of a NATIONAL ELECTRONIC FUNDS TRANSFER SYSTEM OCTOBER 1974 NO. 14 NEW MORTGAGE DESIGNS for an INFLATIONARY ENVIRONMENT JANUARY 1975 NO. 15 NEW ENGLAND and the ENERGY CRISIS OCTOBER 1975 NO. 16 FUNDING PENSIONS: ISSUES and IMPLICATIONS for FINANCIAL MARKETS OCTOBER 1976 NO. 17 MINORITY BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT NOVEMBER, 1976 NO. 18 KEY ISSUES in INTERNATIONAL BANKING OCTOBER, 1977 CONTENTS Opening Remarks FRANK E. MORRIS 7 I. Documenting the Problem 9 Diagnosing the Problem of Inflation and Unemployment in the Western World GEOFFREY H. -

Jan Tinbergen

Jan Tinbergen NOBEL LAUREATE JAN TINBERGEN was born in 1903 in The Hague, the Netherlands. He received his doctorate in physics from the University of Leiden in 1929, and since then has been honored with twenty other degrees in economics and the social sciences. He received the Erasmus Prize of the European Cultural Foundation in 1967, and he shared the first Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Science in 1969. He was Professor of Development Planning, Erasmus University, Rot- terdam (previously Netherlands School of Economics), part time in 1933- 55, and full time in 1955-73; Director of the Central Planning Bureau, The Hague, 1945-55; and Professor of International Economic Coopera- tion, University of Leiden, 1973-75. Utilizing his early contributions to econometrics, he laid the founda- tions for modern short-term economic policies and emphasized empirical macroeconomics while Director of the Central Planning Bureau. Since the mid-1950s, Tinbergen bas concentrated on the methods and practice of planning for long-term development. His early work on development was published as The Design of Development (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1958). Some of his other books, originally published or translated into English, include An Econometric Approach to Business Cycle Problems (Paris: Hermann, 1937); Statistical Testing of Business Cycle Theories, 2 vols. (Geneva: League of Nations, 1939); International Economic Cooperation (Amsterdam: Elsevier Economische Bibliotheek, 1945); Business Cycles in the United Kingdom, 1870-1914 (Amsterdam: North-Holland, 1951); On the Theory of Economic Policy (Amsterdam: North-Holland, 1952); Centralization and Decentralization in Economic Policy (Amsterdam: North-Holland, 1954); Economic Policy: Principles and Design (Amster- dam: North-Holland, 1956); Selected Papers, L. -

Bulletin 27 (1998)

Bulletin of the COUNCIL of UNIVERSITY CLASSICAL DEPARTMENTS Bulletin 27 (1998) Contents Quality Control Christopher Stray Attractive and Nonsensical Classics: Oxford, Cambridge and Elsewhere Christopher Rowe Chairman's Report 1998 Geoffrey Eatough Classics at British Universities, 1997-8: Statistics CUCD Conference Panel, Lampeter 1998: "Graduateness" Charlotte Roueché Greek after Pentecost: The Arguments for Ancient Language 1 Quality Control As anticipated, this has been a busy year for CUCD, and this year's Bulletin for the first time includes a Chairman's Report on the items that have preoccupied us most over the twelve months since Council. As well as a testimony to the energy and efficacy of our current Chair, it reflects CUCD's ever-great enmeshment qua national subject body in the issues of policy and quality we need to influence if we are to defend the things that make our field unique and uniquely resistant to easily assimilation into uniform models of academic structure and outcomes. It remains CUCD strategy here not merely to stay abreast, but where possible to outflank. Even so, the goalposts have been not merely mobile this year but positively skittish, with potentially far-reaching changes in the structures of research funding and academic assessment. We hope that a report from the Chair will help to keep colleagues up to speed with national and subject-specific developments. In this context, the Bulletin retains an especially important role as a forum for current thinking on aims and methods of classical language teaching. Here Charlotte Roueché has recently been pressing a powerfully-argued case for a new role for Greek and Latin as the vehicles for formal language study of a kind largely vanished from the teaching of English and modern languages in schools, but increasingly essential for precisely the new disciplines that are moving towards the centre of the curriculum. -

The Nobel Prize in Economics Turns 50

AEXXXX10.1177/0569434519852429The American EconomistSanderson and Siegfried 852429research-article2019 Article The American Economist 2019, Vol. 64(2) 167 –182 The Nobel Prize in © The Author(s) 2019 Article reuse guidelines: Economics Turns 50 sagepub.com/journals-permissions https://doi.org/10.1177/0569434519852429DOI: 10.1177/0569434519852429 journals.sagepub.com/home/aex Allen R. Sanderson1 and John J. Siegfried2 Abstract The first Sveriges Riksbank Prizes in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel were awarded in 1969, 50 years ago. In this essay, we provide the historical origins of this sixth “Nobel” field, background information on the recipients, their nationalities, educational backgrounds, institutional affiliations, and collaborations with their esteemed colleagues. We describe the contributions of a sample of laureates to economics and the social and political world around them. We also address—and speculate—on both some of their could-have-been contemporaries who were not chosen, as well as directions the field of economics and its practitioners are possibly headed in the years ahead, and thus where future laureates may be found. JEL Classifications: A1, B3 Keywords Economics Nobel Prize Introduction The 1895 will of Swedish scientist Alfred Nobel specified that his estate be used to create annual awards in five categories—physics, chemistry, physiology or medicine, literature, and peace—to recognize individuals whose contributions have conferred “the greatest benefit on mankind.” Nobel Prizes in these five fields were -

Can East Asia Weather a US Slowdown?

About the Paper The ongoing slowdown in the economy of the United States (US) has sparked increasing concerns over the short-term growth prospect of East Asia. Using the Oxford Economics’ Global Model, Cyn-Young Park examines the possible impacts on East Asia of a sharper and longer US slowdown than is currently anticipated in the Asian Development Outlook 2007. The simulation results suggest that a US slowdown on its own would not meaningfully derail East Asia's strong growth. However, in case of significant spillovers from the US slowdown through financial instability and a hard landing in investments in the People’s Republic of China, different growth stories of East Asia may unfold. ERD Working Paper ECONOMICS AND RESEARCH DEPARTMENT About the Asian Development Bank SERIES The work of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) is aimed at improving the welfare of the people in Asia and the Pacific, particularly the 1.9 billion who live on less than $2 a day. Despite many success stories, Asia and the Pacific remains home to two thirds of the world’s poor. ADB is a multilateral development No. finance institution owned by 67 members, 48 from the region and 19 from other parts of the globe. ADB’s vision is a region free of poverty. Its mission is to help its developing member countries reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of their citizens. 95 ADB’s main instruments for providing help to its developing member countries are policy dialogue, loans, technical assistance, grants, guarantees, and equity investments. ADB’s annual lending volume is typically about $6 billion, with technical assistance usually totaling about $180 million a year. -

Equilmrium and DYNAMICS David Gale, 1991 Equilibrium and Dynamics

EQUILmRIUM AND DYNAMICS David Gale, 1991 Equilibrium and Dynamics Essays in Honour of David Gale Edited by Mukul Majumdar H. T. Warshow and Robert Irving Warshow Professor ofEconomics Cornell University Palgrave Macmillan ISBN 978-1-349-11698-0 ISBN 978-1-349-11696-6 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-11696-6 © Mukul Majumdar 1992 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1992 All rights reserved. For information, write: Scholarly and Reference Division, St. Martin's Press, Inc., 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 First published in the United States of America in 1992 ISBN 978-0-312-06810-3 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Equilibrium and dynamics: essays in honour of David Gale I edited by Mukul Majumdar. p. em. Includes bibliographical references (p. ). ISBN 978-0-312-06810-3 1. Equilibrium (Economics) 2. Statics and dynamics (Social sciences) I. Gale, David. II. Majumdar, Mukul, 1944- . HB145.E675 1992 339.5-dc20 91-25354 CIP Contents Preface vii Notes on the Contributors ix 1 Equilibrium in a Matching Market with General Preferences Ahmet Alkan 1 2 General Equilibrium with Infinitely Many Goods: The Case of Separable Utilities Aloisio Araujo and Paulo Klinger Monteiro 17 3 Regular Demand with Several, General Budget Constraints Yves Balasko and David Cass 29 4 Arbitrage Opportunities in Financial Markets are not Inconsistent with Competitive Equilibrium Lawrence M. Benveniste and Juan Ketterer 45 5 Fiscal and Monetary Policy in a General Equilibrium Model Truman Bewley 55 6 Equilibrium in Preemption Games with Complete Information Kenneth Hendricks and Charles Wilson 123 7 Allocation of Aggregate and Individual Risks through Financial Markets Michael J. -

Econometrics As a Pluralistic Scientific Tool for Economic Planning: on Lawrence R

Econometrics as a Pluralistic Scientific Tool for Economic Planning: On Lawrence R. Klein’s Econometrics Erich Pinzón-Fuchs To cite this version: Erich Pinzón-Fuchs. Econometrics as a Pluralistic Scientific Tool for Economic Planning: On Lawrence R. Klein’s Econometrics. 2016. halshs-01364809 HAL Id: halshs-01364809 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01364809 Preprint submitted on 12 Sep 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Documents de Travail du Centre d’Economie de la Sorbonne Econometrics as a Pluralistic Scientific Tool for Economic Planning: On Lawrence R. Klein’s Econometrics Erich PINZÓN FUCHS 2014.80 Maison des Sciences Économiques, 106-112 boulevard de L'Hôpital, 75647 Paris Cedex 13 http://centredeconomiesorbonne.univ-paris1.fr/ ISSN : 1955-611X Econometrics as a Pluralistic Scientific Tool for Economic Planning: On Lawrence R. Klein’s Econometrics Erich Pinzón Fuchs† October 2014 Abstract Lawrence R. Klein (1920-2013) played a major role in the construction and in the further dissemination of econometrics from the 1940s. Considered as one of the main developers and practitioners of macroeconometrics, Klein’s influence is reflected in his application of econometric modelling “to the analysis of economic fluctuations and economic policies” for which he was awarded the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel in 1980. -

Internal Paper

BCN IC hPERS AttAlns coMtwsstoil 0F THE EUR0PEAI| coilitutfftEs o 0|REGT0RATE-GEIIERAL ron Ecotloilllc AtIo FltlA]lclAt No. 39 JuLy 1985 AnaLysis of the stabi Lisation mechanisms of macroeconomic modeLs : a comparison of the EuroLink modets A. BUCHER and V- R0SSI InternaL PaPer "Economic Papers" are written by the Staff of the Directorate-GeneraL for Economic and flnanciaL Affairs, or by experts working in association with them. The "Papers" are intended to increase awareness of the technicaI work being done by the staff and to seek comments and suggestions for further anatyses. They may not be quoted without authorisation. Viel'ls expressed represent excLusiveIy the positions of the author and do not necessari Ly correspond with those of the Commission of the European Communities. Comments and enquiries shoutd be addressed to The Directorate-GeneraI for Economic and FinanciaL Affairs, Commission of the European Communities, 200, rue de ta Loi 1049 BrusseLs, BeLgium ECONOMIC PAPERS No. 39 July 1985 Analysis of the stabilisation mechanisms of macroeconomic models : a comparison of the Eurolink models A. BUCHER and V. ROSSI Internal Paper This paper is only available in English II/92/85-EN ( 1) Contents I Introduction II Evaluating the dominant mechanisms of macroeconomic models III The Expansionary process II1.1 Demand component sensitivity 111.2 Generation of income through labour market adjustment IV Neutrality of the distribution of income IV.l Primary distribution: wage-price nexus IV.2 Redistribution: sectoral transfers V Other constraints to growth V.l Domestic constraints V.2 Open economies and external constraints VI Conclusion Appendix 1: Standardised description of models Appendix 2: Detailed simulation results Bibliography I. -

Involuntary Unemployment Versus "Involuntary Employment" Yasuhiro Sakai 049 Modern Perspective

Articles Introduction I One day when I myself felt tired of writing some essays, I happened to find a rather old book in the corner of the bookcase of my study. The book, entitledKeynes' General Theory: Re- Involuntary ports of Three Decades, was published in 1964. Unemployment versus More than four decades have passed since then. “Involuntary As the saying goes, time and tide wait for no man! 1) Employment” In the light of the history of economic thought, back in the 1930s, John Maynard J.M. Keynes and Beyond Keynes (1936) wrote a monumental work of economics, entitled The General Theory of -Em ployment, Interest and Money. How and to what degree this book influenced the academic circle at the time of publication, by and large, Yasuhiro Sakai seemed to be dependent on the age of econo- Shiga University / Professor Emeritus mists. According to Samuelson (1946), contained in Lekachman (1964), there existed two dividing lines of ages; the age of thirty-five and the one of fifty: "The General Theory caught most economists under the age of thirty-five with the unex- pected virulence of a disease first attacking and decimating an isolated tribe of south sea islanders. Economists beyond fifty turned out to be quite immune to the ailment. With time, most economists in-between be- gan to run the fever, often without knowing or admitting their condition." (Samuelson, p. 315) In 1936, Keynes himself was 53 years old be- cause he was born in 1883. Remarkably, both Joseph Schumpeter and Yasuma Takata were born in the same year as Keynes. -

Macroeconomic Dynamics at the Cowles Commission from the 1930S to the 1950S

MACROECONOMIC DYNAMICS AT THE COWLES COMMISSION FROM THE 1930S TO THE 1950S By Robert W. Dimand May 2019 COWLES FOUNDATION DISCUSSION PAPER NO. 2195 COWLES FOUNDATION FOR RESEARCH IN ECONOMICS YALE UNIVERSITY Box 208281 New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8281 http://cowles.yale.edu/ Macroeconomic Dynamics at the Cowles Commission from the 1930s to the 1950s Robert W. Dimand Department of Economics Brock University 1812 Sir Isaac Brock Way St. Catharines, Ontario L2S 3A1 Canada Telephone: 1-905-688-5550 x. 3125 Fax: 1-905-688-6388 E-mail: [email protected] Keywords: macroeconomic dynamics, Cowles Commission, business cycles, Lawrence R. Klein, Tjalling C. Koopmans Abstract: This paper explores the development of dynamic modelling of macroeconomic fluctuations at the Cowles Commission from Roos, Dynamic Economics (Cowles Monograph No. 1, 1934) and Davis, Analysis of Economic Time Series (Cowles Monograph No. 6, 1941) to Koopmans, ed., Statistical Inference in Dynamic Economic Models (Cowles Monograph No. 10, 1950) and Klein’s Economic Fluctuations in the United States, 1921-1941 (Cowles Monograph No. 11, 1950), emphasizing the emergence of a distinctive Cowles Commission approach to structural modelling of macroeconomic fluctuations influenced by Cowles Commission work on structural estimation of simulation equations models, as advanced by Haavelmo (“A Probability Approach to Econometrics,” Cowles Commission Paper No. 4, 1944) and in Cowles Monographs Nos. 10 and 14. This paper is part of a larger project, a history of the Cowles Commission and Foundation commissioned by the Cowles Foundation for Research in Economics at Yale University. Presented at the Association Charles Gide workshop “Macroeconomics: Dynamic Histories. When Statics is no longer Enough,” Colmar, May 16-19, 2019.