Cross-Validation of Two Supervision Instruments with Counseling Trainees From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Practice Newsletter Edition 9 – Summer 2019

Practice Newsletter Edition 9 – Summer 2019 Inside this Edition Page 2. Team News Page 3. Access to Appointments Page 4. E-Consult – the introduction of on-line consultations Page 5. Primary Care Networks. Public Meeting – Liverpool Heart and Chest Hospital Page 6. Practice News and Events. There are 2 important changes at the practice which are both happening on 1st July We will be switching on E-Consult on July 1st which will provide our patients with the facility to consult with our GPs via an on-line consultation. This is a truly significant development in the way we interact with our patients and you can find out more about it on page 4 of this newsletter. On the same day we will be changing our booking process for same-day appointments so that these will only be available via the phone from 8:30 am. This means that you will not be able to book an appointment by queuing up at the reception desk when we open. The practice has issued an information sheet for patients which explains why we have had to make this change. It is on our website and can be viewed via the QR code. Copies are also available at the Reception Desk. We hope you enjoy our newsletter and find it informative. We look forward to hearing your feedback. Visit our new website at www.ainsdalemedicalcentre.nhs.uk And follow us on social media as @ainsdaledocs Ainsdale Medical Centre Newsletter – Summer 2019 Page 1 | 6 Team News Dr Richard Wood will be retiring from the Partnership at the end of July. -

Operator Address Seaforth Radio Cars Incorporating One Call 105

Operator Address Seaforth Radio Cars Incorporating One Call 105 Bridge Road Liverpool Merseyside L21 2PB L & N Travel 233 Meols Cop Road Southport Merseyside PR8 6JU Delta Merseyside Ltd 200 Strand Road Bootle Merseyside L20 3HL Cyllenius Airport Travel Services 100 Derby Road Unit 1501 Bootle L20 1BP Glenn Travel AIRPORTTRANSFERS247.COM LTD Suite 12 39A Sefton Lane Industrial Estate Maghull L31 8BX Prince Executive Cars Letusgetyouthere 8 Fenton Close Bootle Merseyside L30 1TE GoingtotheAirport.co.uk 12 Bridge Road Liverpool Merseyside L23 6SG Cavalier Travel 73 Bridge Road Liverpool Merseyside L21 2PA Phoenix Cars 17a Elbow Lane Formby Merseyside L37 4AB Dixons Direct Central Cars Southport 161 Eastbank Street, Southport Merseyside PR8 6TH All White Taxis 181-183 Eastbank Street Southport Merseyside PR8 6TH Steve's Shuttle Service Blueline 50 Private Hire 54/56 Station Road, Liverpool Merseyside L31 3DB Taylor Made Tours of Liverpool Ltd 2 Village Courts Liverpool Merseyside L30 7RE Formby Village Radio Cars 36C Chapel Lane, Liverpool Merseyside L37 4DU Phil's Airport Transport David Bragg R & R Airport Transfer Specialist 12 Wineva Gardens Liverpool Merseyside L23 9SJ Travel 2000 62 Bedford Road Southport Merseyside PR8 4HJ Anytime Travel 38 Trevor Drive Liverpool Merseyside L23 2RW Liverpool VIP Travel 23 Truro Avenue Netherton Bootle Merseyside L30 5QR A.P.L Executive Travel 1 Lower Alt Road Liverpool Merseyside L38 0BA PJ Chauffeur Services 43 Chesterfield Road Liverpool Merseyside L23 9XL A & S Travel 11a Oakwood Avenue Southport Merseyside PR8 3HX Ennis David T/A Upgrade Travel ( sole trader ) Airport Distance Local 38 Larkfield Lane Southport Merseyside PR9 8NW Acorn Cars Maghull Business Centre Liverpool Merseyside L31 2HB Aintree Lane Travel 104 Aintree Lane Liverpool Merseyside L10 2JW Kwik Cars (North West) Ltd 3 St Lukes Road Southport Merseyside PR9 0SH Johns Travel Nicholson Mullis Ltd. -

Complete List of Roads in Sefton ROAD

Sefton MBC Department of Built Environment IPI Complete list of roads in Sefton ROAD ALDERDALE AVENUE AINSDALE DARESBURY AVENUE AINSDALE ARDEN CLOSE AINSDALE DELAMERE ROAD AINSDALE ARLINGTON CLOSE AINSDALE DORSET AVENUE AINSDALE BARFORD CLOSE AINSDALE DUNES CLOSE AINSDALE BARRINGTON DRIVE AINSDALE DUNLOP AVENUE AINSDALE BELVEDERE ROAD AINSDALE EASEDALE DRIVE AINSDALE BERWICK AVENUE AINSDALE ELDONS CROFT AINSDALE BLENHEIM ROAD AINSDALE ETTINGTON DRIVE AINSDALE BOSWORTH DRIVE AINSDALE FAIRFIELD ROAD AINSDALE BOWNESS AVENUE AINSDALE FAULKNER CLOSE AINSDALE BRADSHAWS LANE AINSDALE FRAILEY CLOSE AINSDALE BRIAR ROAD AINSDALE FURNESS CLOSE AINSDALE BRIDGEND DRIVE AINSDALE GLENEAGLES DRIVE AINSDALE BRINKLOW CLOSE AINSDALE GRAFTON DRIVE AINSDALE BROADWAY CLOSE AINSDALE GREEN WALK AINSDALE BROOKDALE AINSDALE GREENFORD ROAD AINSDALE BURNLEY AVENUE AINSDALE GREYFRIARS ROAD AINSDALE BURNLEY ROAD AINSDALE HALIFAX ROAD AINSDALE CANTLOW FOLD AINSDALE HARBURY AVENUE AINSDALE CARLTON ROAD AINSDALE HAREWOOD AVENUE AINSDALE CHANDLEY CLOSE AINSDALE HARVINGTON DRIVE AINSDALE CHARTWELL ROAD AINSDALE HATFIELD ROAD AINSDALE CHATSWORTH ROAD AINSDALE HEATHER CLOSE AINSDALE CHERRY ROAD AINSDALE HILLSVIEW ROAD AINSDALE CHESTERFIELD CLOSE AINSDALE KENDAL WAY AINSDALE CHESTERFIELD ROAD AINSDALE KENILWORTH ROAD AINSDALE CHILTERN ROAD AINSDALE KESWICK CLOSE AINSDALE CHIPPING AVENUE AINSDALE KETTERING ROAD AINSDALE COASTAL ROAD AINSDALE KINGS MEADOW AINSDALE CORNWALL WAY AINSDALE KINGSBURY CLOSE AINSDALE DANEWAY AINSDALE KNOWLE AVENUE AINSDALE 11 May 2015 Page 1 of 49 -

Background Information for Candidates

Background Information for Candidates Primary Care Networks From July 2019, NHS England made funding available for Primary Care Networks, through the national GP contract, for the creation of 7.5 Link Workers (FTE) who will work across the 7 Primary Care Networks in Sefton. A Primary Care Network (PCN) consist of groups of general practices working together with a range of local providers, including across primary care, community services, social care and the voluntary sector to offer more personalised, coordinated health and social care to their local population. Each PCN serves a patient population of between 30 and 50k. There are 7 PCN’s in Sefton. These are Bootle, Seaforth and Litherland, Crosby and Maghull, Formby, Ainsdale and Birkdale, Central Southport and North Southport. Primary Care Networks are an integral part of the recently published NHS Long-Term Plan which introduces this new role of social prescribing link workers into their multi-disciplinary teams as part of the expansion to the primary care workforce. This is an opportunity to work collaboratively with these developing PCN’s to establish this new role and shape social prescribing in Sefton. Social Prescribing Link Workers In December and January Sefton CVS recruited 7.5 FTE Social Prescribing Link Workers on behalf of host organisations, to support the delivery of a social prescribing service for Primary Care Networks in Sefton as part of the award winning Living Well Sefton programme. The social prescribing link workers are employed by a range of partner organisations working across the borough but function as one social prescribing team alongside Living Well Mentors in the wider service. -

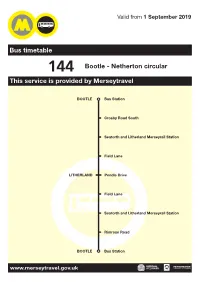

144 Bootle - Netherton Circular This Service Is Provided by Merseytravel

Valid from 1 September 2019 Bus timetable 144 Bootle - Netherton circular This service is provided by Merseytravel BOOTLE Bus Station Crosby Road South Seaforth and Litherland Merseyrail Station Field Lane LITHERLAND Pendle Drive Field Lane Seaforth and Litherland Merseyrail Station Rimrose Road BOOTLE Bus Station www.merseytravel.gov.uk What’s changed? The route is shortened. Journeys now only travel as far as Pendle Drive and Bowland Drive before heading back to Bootle. Service no longer serves Magdalene Square. Times are changed. Any comments about this service? If you’ve got any comments or suggestions about the services shown in this timetable, please contact the bus company who runs the service: Hatton’s Travel 224 North Florida Road, Haydock, St Helens WA11 9TP. 01744 811818 HTL Buses 37 Wilson Road, Liverpool, L36 6AN 0151 449 3868 Contact us at Merseytravel: By e-mail [email protected] By phone 0151 330 1000 In writing PO Box 1976, Liverpool, L69 3HN Need some help or more information? For help planning your journey, call 0151 330 1000, open 0800 - 2000, 7 days a week You can visit one of our Travel Centres across the Merseytravel network to get information about all public transport services. To find out opening times, phone us on 0151 330 1000. Our website contains lots of information about public transport across Merseyside. You can visit our website at www.merseytravel.gov.uk Bus services may run to different timetables during bank and public holidays, so please check your travel plans in advance. Large print timetables We can supply this timetable in another format, such as large print. -

Download Original Attachment

STREET ALBERT ROAD ALTWAY BISPHAM ROAD BRIDGE ROAD BRIDGE ROAD CAMBRIDGE ROAD CAMBRIDGE ROAD CEMETERY ROAD CHURCH ROAD CHURCH ROAD CROWLAND STREET HATTON HILL ROAD KNOWSLEY ROAD LINACRE LANE LIVERPOOL ROAD LIVERPOOL ROAD LIVERPOOL ROAD LIVERPOOL ROAD LIVERPOOL ROAD LIVERPOOL ROAD SOUTH LORD STREET MARINE DRIVE MARINE PARADE MARSH LANE MARSH LANE MARSH LANE ORRELL ROAD ORRELL ROAD ORRELL ROAD ORRELL ROAD PARK ROAD QUEENS ROAD RUFFORD ROAD SANDY ROAD SANDY ROAD SCARISBRICK NEW ROAD SCARISBRICK NEW ROAD SEAFORTH ROAD SEAFORTH ROAD SEAFORTH ROAD TREVOR DRIVE WADDICAR LANE WADDICAR LANE WATERLOO ROAD WATERLOO ROAD WATTS LANE WORCESTER ROAD NORWOOD AVENUE ADDRESS SOUTHPORT, OPPOSITE NO 79 AT ENTRANCE TO PARK, AINTREE, OUTSIDE HOUSE NO 11, SOUTHPORT, O/S 100 CROSBY, JUN RIVERSLEA RD CROSBY, JNC HARLECH RD SOUTHPORT, BY L/C 16 JCT COCKLEDICKS LN. SOUTHPORT, o/s BOLD HOTEL, SOUTHPORT, OUTSIDE NO 117 FORMBY, O/S KENSINGTON COURT OPP AMBULANCE STATION, FORMBY, O/S HOUSE NO 99 ADJ TO FIRE STATION, SOUTHPORT, JCT WENNINGTON ROAD, O/S 14 /16 LITHERLAND, O/S ST PAULS CHURCH, BOOTLE, S/L COL 24A BOOTLE, O/S 138 AINSDALE, JNC WITH BURNLEY ROAD, AINSDALE, SIDE OF NO 2 LIVERPOOL AVE BIRKDALE, JCT SHAWS RD BIRKDALE, O/S 297 JCT FARNBOROUGH RD FORMBY, O/S 78 MAGHULL, L/COL NO 26 SOUTHPORT, O/S POST OFFICE SOUTHPORT, SLUICE GATES ADJ TO SEA SCOUT CENTRE SOUTHPORT, LAMP COLUMN 3 BY McDonalds BOOTLE, O/S NO 61/63 BOOTLE, O/S 125 BOOTLE, O/S ST JAMES SCHOOL JCT CHESNUT GROVE BOOTLE, O/S 38 ON S/L COL 5A BOOTLE, O/S NO 69 ON COL 12A LITHERLAND, ON COL 23A LITHERLAND, -

Cycle Sefton!

G E ' S L A N E t anspor Tr ac Tr cling Cy ing lk Wa ublic ublic P Southport CH A RN In association with LE A Y'S LA NE MARINE DRIVE Cycling is great because it’s… Fresh Air RALPH'S WIFE'S LANE NE LA 'S Fitness FE I W H'S Banks LP RA S M6 KI PT Fun ON H AV A EN R U R E O G A58 A T D For the whole family E C E A U W R A OAD Sefton CouncilN E Y RO N R N O E I Sefton Council S T O TA T S R S V S C G K U A IN E E N B5204 V K N F I F O T A R O R B R Low cost travel D RU E E Y T D N A N I W G A D R L LE R A N E I O E N U T M T CN V V D S Crossens E A C N E E A I R IV S O E E C A S 5 L R Y S N 65 ANCA R D O V O W STE N R Y A M T T Door to door L A S ER E E R G LA I N T R L D M K IN E E M L R N A S A IV O F R L R E M Y S A A A ' E EW H I S S S D U ID A B P C Pollution free E U A T E Y S R R C CN H O A N E E S A A CR T C D W C FT R RO E AUSEWAY N SC C E E E N TH O T D V G T A H I O I N A A R D O E AD S R E D R A O R S S YL D O POOL STREET R N K T F K I A K R IC D B P R This map shows cycle lanes and suggested routes W A Y N LS O R E R G G A W NG R O L P E TA O A R E E N BROOK STREET S D A D O N R AR A D A P E N G O F A around Sefton avoiding busy roads and junctions. -

Depot Road, Kirkby, Knowsley L33 3AR the Joseph Lappin Centre Mill

Depot Road, Kirkby, Knowsley L33 3AR The Joseph Lappin Centre Mill Lane Old Swan Liverpool L13 5TF 37 Otterspool Drive, Liverpool Crosby Leisure Centre Mariners Road, Liverpool 100 Sefton Lane, Maghull Cronton Community Hall, Cronton Road , Widnes, WA8 5QG Unit 3 105 Boundary Street Liverpool L5 9YJ 35 Earle Rd, Liverpool, Merseyside L7 6HD St Helens Road Ormskirk Lancashire & Various Locations The Old School House, St John's Road, Huyton, L36 0UX The Millennium Centre, View Rd, Rainhill, L35 0LE Catalyst Science Discovery Centre, Mersey Road, Widnes. Twist Lane, Leigh 45 Mersey View Brighton Le Sands Crosby, Liverpool. Arthog Gwynedd Wales St Albans Church, Athol St, Liverpool Storeton Lane Barnston Wirral CH61 1BX 48 Southport Road Ormskirk Multiple Locations Beechley Riding Stables Harthill Road Allerton Liverpool Merseyside L18 3HU 4 Priory Street Birkenhead Merseyside CH41 5JH 65 Knowles Street, Radcliffe, Manchester. M26 4DU Write Blend Bookshop South Road Waterloo North Park Washington Parade Bootle Merseyside L20 5JJ Halewood Leisure Centre Baileys Lane Halewood Knowsley Liverpool L26 0TY Multiple locations (See Children’s University Website) Burrows Lane, Prescot, L34 6JQ Bobby Langton Way 1st floor Evans House Norman Street Warrington Liverpool Clockface Miners Recreation Club, Crawford Street, St Helens WA94QS Multiple Locations St Aloysius Catholic Primary School Twig Ln, Huyon St Lukes Church Hall, Liverpool Road Crosby Sacred Heart Dance Centre, Marldon Avenue Crosby Back Lane, Little Crosby, Liverpool, Post code L23 4UA -

Bootle Selective Licencing Area

Bootle Selective Licensing Boundary – List of included roads Road Name Ward ADDISON STREET Linacre AINTREE ROAD (Numbers 1 -64) Derby AKENSIDE STREET Linacre ALPHA STREET Litherland ALT ROAD Litherland ALTCAR ROAD Litherland ANTONIO STREET Derby ANVIL CLOSE Linacre ARCTIC ROAD Linacre ASH GROVE Linacre ASH STREET Derby ASHCROFT STREET Linacre ATLANTIC ROAD Linacre ATLAS ROAD Linacre AUGUST STREET Derby AUTUMN WAY Derby AYLWARD PLACE Linacre BACK STANLEY ROAD Derby BALFE STREET Linacre BALFOUR AVENUE Linacre BALFOUR ROAD Linacre BALLIOL ROAD Derby BALLIOL ROAD EAST Derby BALTIC ROAD Linacre BANK ROAD Linacre BARKELEY DRIVE Linacre BARNTON CLOSE Litherland BEATRICE STREET Linacre BECK ROAD Litherland BEDFORD PLACE Linacre BEDFORD ROAD (Numbers 1 – 277) Linacre BEECH GROVE Linacre BEECH STREET Derby BEECHWOOD ROAD Litherland BELLINI CLOSE Linacre BENBOW STREET Linacre BENEDICT STREET Linacre BERESFORD STREET Linacre BERGEN CLOSE Derby BERRY STREET Linacre BIANCA STREET Linacre BIBBYS LANE Linacre BLISWORTH STREET Litherland BLOSSOM STREET Derby BOSWELL STREET Linacre BOWDEN STREET Litherland BOWLES STREET Linacre BRABY ROAD Litherland BRASENOSE ROAD Linacre Road Name Ward BREEZE HILL (Numbers 1 – 48) Derby BREWSTER STREET (Numbers 46 – 100) Derby BRIDGE ROAD Litherland BRIDGE STREET Linacre BROMYARD CLOSE Linacre BROOK ROAD Linacre BROOKHILL CLOSE Derby BROOKHILL ROAD Derby BROWNING STREET Linacre BRYANT ROAD Litherland BULWER STREET Linacre BURNS STREET Linacre BUSHLEY CLOSE Linacre BYNG STREET Linacre BYRON STREET Linacre CAMBRIDGE ROAD -

Annual Air Quality Status Report 2019

2019 Air Quality Annual Status Report (ASR) In fulfilment of Part IV of the Environment Act 1995 Local Air Quality Management July 2019 LAQM Annual Status Report 2019 i Local Authority Greg Martin Officer Iain Robbins Department Highways and Public Protection Magdalen House, 30 Trinity Road, Bootle. Address L20 3NJ Telephone 0151 934 2098 E-mail [email protected] Report Reference Sefton ASR 2019 number Date August 2019 Name Position Signed Date Prepared Greg Principal by Martin Environmental 20/08/19 Health Officer Reviewed Terry Environmental by Wood Health & 20/08/19 Licensing Manager Approved Matthew Director of by Ashton Public Health 03/09/19 Approved Peter Head of by Moore Highways and Public 03/09/19 Protection LAQM Annual Status Report 2019 ii Forward by Director of Public Health Sefton Council is committed to improving Air Quality in the Borough and is working to ensure that Sefton will be a place where improved health and wellbeing is experienced by all. This work directly supports Sefton’s 2030 vision of a cleaner, greener and healthier Borough. Poor air quality has a negative impact on public health, with potentially serious consequences for individuals, families and communities. Identifying problem areas and ensuring that actions are taken to improve air quality forms an important element in protecting the health and wellbeing of Sefton’s residents. Air Quality in the Majority of Sefton is of a good standard, however, a small number of areas in the South of the Borough have been identified where additional targeted actions are likely to be required to bring about further air quality improvements. -

Sefton Council Election Results 1973-2012

Sefton Council Election Results 1973-2012 Colin Rallings and Michael Thrasher The Elections Centre Plymouth University The information contained in this report has been obtained from a number of sources. Election results from the immediate post-reorganisation period were painstakingly collected by Alan Willis largely, although not exclusively, from local newspaper reports. From the mid- 1980s onwards the results have been obtained from each local authority by the Elections Centre. The data are stored in a database designed by Lawrence Ware and maintained by Brian Cheal and others at Plymouth University. Despite our best efforts some information remains elusive whilst we accept that some errors are likely to remain. Notice of any mistakes should be sent to [email protected]. The results sequence can be kept up to date by purchasing copies of the annual Local Elections Handbook, details of which can be obtained by contacting the email address above. Front cover: the graph shows the distribution of percentage vote shares over the period covered by the results. The lines reflect the colours traditionally used by the three main parties. The grey line is the share obtained by Independent candidates while the purple line groups together the vote shares for all other parties. Rear cover: the top graph shows the percentage share of council seats for the main parties as well as those won by Independents and other parties. The lines take account of any by- election changes (but not those resulting from elected councillors switching party allegiance) as well as the transfers of seats during the main round of local election. -

Walking & Cycling Newsletter

Sefton’s Autumn Walking & Cycling Newsletter Issue 45 / October – December 2017 It’s a great time of the year to enjoy the Autumnal colours on our walks and rides. Contents Walking Cycling Walking Diary 3 Cycling Diary 23 Monday 4 Pedal Away 24 Maghull Health Walks Southport Hesketh Centre 25 Netherton Feelgood Factory Health Walks Ride Programme Macmillan Rides 25 Crosby Health Walks Tour de Friends 26 Ainsdale Health Walks The Chain Gang 27 Tuesday 6 Tyred Rides 28 Bootle Health Walks Bike Tagging 28 Hesketh Park Health Walks Ditch the Stabilisers 29 Formby Pinewoods Health Walks Dr Bike – Free Bicycle Maintenance 30 Walking Diary Box Tree Health Walks Wheels for All 31 Waterloo Health Walks Active Walks is Sefton’s Please arrive 15 mins early for your first Wednesday 8 Freewheeling 31 walk as you will need to fill in a Registration Wednesday Social Walks local health walk Form. Seaforth Health Walks programme and offers Please note: Please attend a Grade 3 walk Take a walk on the Lakeside before joining a Progressional Walk. Introduction a significant number Progressional Walks: brisk pace, varied Sefton Trailblazers Walking and cycling is a great way of regular walking groups terrain, can include stiles/steps/gradients Litherland Sports Park Walking Club of keeping active and healthy if and uneven surfaces. Thursday 10 done on a regular basis. We should across Sefton. The walks Guide dogs are allowed on all health walks. Formby Pool Health Walks be doing at least 150 minutes continue throughout Grade 1: suitable for people who have not Prambles of physical activity every week the year and are led walked much before.