How Close Are the Co-Movements of Main Currencies?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

European Interview N°73 with Dalia Grybauskaitė

INTERVIEW WITH DALIA GRYBAUSKAITĖ European interview n°73 “The Euro is not only currency; nd 22 July 2013 it is first of all the responsible and sustainable fiscal policy” Interview with Dalia Grybauskaitė, President of the Republic of Lithuania per cent, but more could be achieved, among others by 1. The Lithuanian Presidency of the Council of implementing the measures already agreed on EU level. the European Union - 1st July to 31st December Lithuania will also pursue the EU commitment to com- 2013 – is taking place at a key moment in the plete the internal energy market by 2014 and en- European political agenda. Indeed it is the sure that no Member State remains isolated from the last full Presidency to take place before the European energy networks as of 2015. Digital Agenda, institutions are renewed again in 2014. Some research and innovations are also among priorities. major legislative decisions will be taken during We cannot forget about the EU’s external partners and this term in office. What are the priorities of the our vision of an open Europe. The Presidency will focus Lithuanian Presidency? What do you want and on the closer integration between the EU and its Eastern what can you achieve in six months? Partners and host the EU‘s Eastern Partnership Summit in November 2013 in Vilnius. The agenda also includes The Lithuanian Presidency [1], just like the French a smarter control of the EU’s external borders and pro- Presidency in the second half of 2008, will be the last motion of free trade with strategic partners. -

What Decides the Exchange Rate? Theory – and Predictions of the Norwegian Krone Against the Euro

Archives of Business Research – Vol.6, No.6 Publication Date: June. 25, 2018 DOI: 10.14738/abr.66.4827. Vale, P. H. (2018). What Decides the Exchange Rate? Theory – and Predictions of the Norwegian Krone against the Euro. Archives of Business Research, 6(6), 353-365. What Decides the Exchange Rate? Theory – and Predictions of the Norwegian Krone against the Euro Per Halvor Vale Norwegian University of Life Sciences, SChool of EConomiCs and Business ABSTRACT The paper analyses changes in the exchange rate of the Norwegian krone (NOK) as measured against the Euro, with the purpose of forecasting future exchange rates. The analysis is based on an error correction model. The model is given an autoregressive form. From the model is derived “out-of-sample forecast”. The predictions are compared with forecasts obtained from a Random Walk model. The empirical findings show that even though the economic model identifies several important explanatory variables, the Random Walk model performs better. Kewords: ExChange rate, equilibrium exChange rate, out-of-sample foreCasts JEL classification: C22C32, C53, F31 INTRODUCTION It is important for deCision-makers in eConomiC seCtor to have a Clear idea as to the Causes of fluctuations in the exchange rate. This paper analyses variations and shifts in the exchange rate of the Norwegian CurrenCy measured against the euro. The purpose is to understand the driving forCes and make prediCtions about likely Changes in future exChange rates. To test the viability of the model we blank out some of the sample data and make “out-of-sample foreCasts”. The foreCast model is Challenged by a Random Walk model (RW). -

Annual Report 2007

4 THE CASH CHANGEOVER IN CYPRUS AND MALTA Six years after the successful introduction of the Monnaie de Paris minted 200.0 million euro coins euro banknotes and coins in 12 euro area countries with a face value of €56.1 million for Malta. at the same time and one year after Slovenia joined the Eurosystem, the euro banknotes and The Central Bank of Cyprus began frontloading coins were successfully introduced in Cyprus and euro coins to credit institutions on 22 October 2007; Malta on 1 January 2008. After a dual circulation the frontloading of euro banknotes began on period of one month, the euro had fully replaced 19 November 2007. Sub-frontloading to retailers the Cyprus pound and the Maltese lira. and the cash-operated machine industry started at the same time as the frontloading operation. As in the previous cash changeovers, timely and A widespread predistribution of euro coins was comprehensive preparation was crucial to the supported by making some 40,000 pre-packed smooth introduction of the euro banknotes and coin starter kits, worth €172 each, available to coins. Both Cyprus and Malta had established businesses and retailers from 3 December 2007. changeover plans at the national level long 250,000 mini-kits, worth CYP 10 each, went on before €-Day. These plans were based on, among sale to the general public on the same date. other things, the legal framework adopted by the Governing Council in July 2006 in relation to In Malta the frontloading of euro coins started certain preparations for the euro cash changeover in late September 2007, while the frontloading and the frontloading and sub-frontloading of euro of euro banknotes began in late October. -

The Maltese Lira

THE MALTESE LIRA On 16 May 1972, the Central Bank of Malta issued the first series of decimal coinage based on the Maltese Lira, at the time being roughly equivalent to the British Pound. Each Lira was divided in 100 cents (abbreviation of centesimo, meaning 1/100), while each cent was subdivided in 10 mills (abbreviation of millesimo, meaning 1/1000). The mills coins of the 1972 series - withdrawn from circulation in 1994 9 COINS AND 3 BANKNOTES Initially, a total of 8 coins were issued, namely the 50 cent, 10 cent, 5 cent, 2 cent, 1 cent, 5 mill, 3 mill and 2 mill. These coins were complemented by the issue of three banknotes, namely the 1 Lira, 5 Lira and 10 Lira, on 15 January 1973. Furthermore, a 25 cent coin was introduced in June 1975 to commemorate Malta becoming a Republic within the Commonwealth of Nation on 13 December 1974. This was the first coin to feature the coat of arms of the Republic of Malta on the reverse. NEW SERIES The obverse of the 1986/1991 series - withdrawn from circulation in January 2008 A new series was issued on 19 May 1986. This comprised 7 coins, namely the 1 Lira, 50 cent, 25 cent, 10 cent, 5 cent, 2 cent and 1 cent. Each coin depicted local fauna and flora on the The banknotes of the 1989 series - withdrawn from circulation in January 2008 obverse and the emblem of the Republic on the reverse. No mills were struck as part of this series, though the 5 mil, 3 mil and 2 mil coins issued in 1972 continued to have legal tender. -

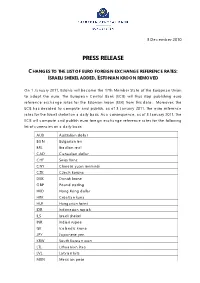

Press Release Changes to the List of Euro Foreign Exchange Reference

3 December 2010 PRESS RELEASE CHANGES TO THE LIST OF EURO FOREIGN EXCHANGE REFERENCE RATES: ISRAELI SHEKEL ADDED, ESTONIAN KROON REMOVED On 1 January 2011, Estonia will become the 17th Member State of the European Union to adopt the euro. The European Central Bank (ECB) will thus stop publishing euro reference exchange rates for the Estonian kroon (EEK) from this date. Moreover, the ECB has decided to compute and publish, as of 3 January 2011, the euro reference rates for the Israeli shekel on a daily basis. As a consequence, as of 3 January 2011, the ECB will compute and publish euro foreign exchange reference rates for the following list of currencies on a daily basis: AUD Australian dollar BGN Bulgarian lev BRL Brazilian real CAD Canadian dollar CHF Swiss franc CNY Chinese yuan renminbi CZK Czech koruna DKK Danish krone GBP Pound sterling HKD Hong Kong dollar HRK Croatian kuna HUF Hungarian forint IDR Indonesian rupiah ILS Israeli shekel INR Indian rupee ISK Icelandic krona JPY Japanese yen KRW South Korean won LTL Lithuanian litas LVL Latvian lats MXN Mexican peso 2 MYR Malaysian ringgit NOK Norwegian krone NZD New Zealand dollar PHP Philippine peso PLN Polish zloty RON New Romanian leu RUB Russian rouble SEK Swedish krona SGD Singapore dollar THB Thai baht TRY New Turkish lira USD US dollar ZAR South African rand The current procedure for the computation and publication of the foreign exchange reference rates will also apply to the currency that is to be added to the list: The reference rates are based on the daily concertation procedure between central banks within and outside the European System of Central Banks, which normally takes place at 2.15 p.m. -

1 TREASURY REPORTING RATES of EXCHANGE As of December 31, 2009 Foreign Currency Country-Currency to $1.00

04/29/15 Page: 1 TREASURY REPORTING RATES OF EXCHANGE As of December 31, 2009 Foreign Currency Country-Currency To $1.00 Afghanistan-Afghani 47.9200 Albania-Lek 95.4300 Algeria-Dinar 70.3330 Angola-Kwanza 75.0000 Antigua & Barbuda-E. Caribbean Dollar 2.7000 Argentina-Peso 3.7980 Armenia-RUBLE 375.0000 Australia-Dollar 1.1110 Austria-Euro .6950 Austria-Schilling .0000 Azerbaidjan-Ruble .8200 Azerbaijan-New Manat .0000 Bahamas-Dollar 1.0000 Bahrain-Dinar .3770 Bangladesh-Conv. Taka .0000 Bangladesh-Non-Conv. Taka 68.0000 Barbados-Dollar 2.0200 Belarus-Ruble 2,880.0000 Belgium-Euro .6950 Belgium-Franc .0000 Belize-Dollar 2.0000 Benin-CFA Franc 454.8900 Bermuda-Dollar 1.0000 Bolivia-Boliviano 6.9700 Bosnia-Dinar 1.3590 Botswana-Pula 6.6530 Brazil-Cruzados .0000 Brazil-Cruzeiro 1.7400 Brunei-Dollar 1.4010 Bulgaria-Lev 1.3580 Burkina Faso-CFA Franc 454.8900 Burma-Kyat 450.0000 Burundi-Franc 1,200.0000 Cambodia (Khmer)-Riel 4,163.0000 Cameroon-CFA Franc 454.8900 Canada-Dollar 1.0510 Cape Verde-Escudo 74.7270 Cayman Island-Dollar .0000 Central African Rep.-CFA Franc 454.8900 Chad-CFA Franc 454.8900 Chile-Peso 507.0000 China-Renminbi 6.8260 China-Yuan .0000 Colombia-Peso 2,046.5000 Comoros-CFA Franc 361.3500 Congo-CFA Franc 454.8900 Costa Rica-Colon 553.7000 Croatia-KUNA 5.0000 Cuba-Peso .9260 Cyprus-Euro .0000 Cyprus-Pound .0000 Czech. Republic-Koruna 18.1190 Czechoslovakia-Tuzex Koruna .0000 CFA Franc-CFA Franc .0000 Dem. Rep. of Congo-Congolese Franc 900.0000 Denmark-Kroner 5.1670 Djibouti-Franc 177.0000 Dominican Republic-Peso 36.1000 East Germany-GDR Mark .0000 Ecuador-Dollar 1.0000 Ecuador-Sucre .0000 Egypt-Pound 5.4840 El Salvador-Colon 1.0000 Equatorial Guinea-CFA Franc 454.8900 Eritrea-Birr 15.0000 Estonia-EURO .0000 Estonia-Kroon 10.8650 04/29/15 Page: 2 TREASURY REPORTING RATES OF EXCHANGE As of December 31, 2009 Foreign Currency Country-Currency To $1.00 Ethiopia-Birr 12.6400 Euro-Euro .6950 European Community-European Comm. -

The Krone Exchange Rate and Competitiveness in the Business Sector

Svein Gjedrem: The krone exchange rate and competitiveness in the business sector Address by Mr Svein Gjedrem, Governor of Norges Bank (Central Bank of Norway), to the Federation of Norwegian Process Industries, Oslo, 29 April 2004. The text below may differ slightly from the actual presentation. The address is based on the assessments presented at Norges Bank’s press conference following the Executive Board’s monetary policy meeting on 21 April, Inflation Report 1/04 and on previous speeches. The charts can be found on the Norges Bank’s website. * * * The primary objective of monetary policy is to ensure nominal stability. There were wide fluctuations in the Norwegian economy in the 1970s and 1980s. Economic developments were marked by high and variable inflation. Inflation rose gradually and it took a long time before it fell. The absence of a nominal anchor was one of the main reasons behind these pronounced swings in the Norwegian economy. With a policy of low interest rates and devaluations, inflation took root. Nominal interest rates were kept at a low level even though inflation and the value of tax-deductible interest expenditure rose. Frequent devaluations from 1976 were not able to prevent a decline in the manufacturing sector. On the contrary, they proved to be self-reinforcing. The wide fluctuations culminated in a credit boom in the mid-1980s, and a rise in costs as a consequence of the spring 1986 wage settlement. A pronounced downturn and high unemployment followed at the end of the 1980s. In order to achieve nominal stability, monetary policy must provide a nominal anchor. -

Svein Gjedrem: Monetary Policy from a Historical Perspective (Central

Svein Gjedrem: Monetary policy from a historical perspective Speech by Mr Svein Gjedrem, Governor of Norges Bank (Central Bank of Norway), at the conference to mark the 100th anniversary of the Association of Norwegian Economists, Oslo, 16 September 2008. The text may differ slightly from the actual presentation. * * * Introduction Let me begin by offering my congratulations to the Association of Norwegian Economists on its 100th anniversary. One hundred is a respectable age. In Norway, the introduction of a university degree in economics was certainly an important stimulus in the first part of the last century. In the period since the Second World War, major changes in society have increased the demand for expertise in the field of economics. And economists are constantly gaining new insights. This also applies to the field of central banking, even though one of the fundamental central bank responsibilities – to safeguard the value of money – was as important 100 years ago as it is today. Monetary policy in Norway has changed considerably over the past 100 years. The government, with the support of the Storting, has now defined an objective for monetary policy of low and stable inflation. Norges Bank sets its interest rate with a view to achieving price stability. This has not always been the case. Monetary policy in Norway Norges Bank was established in 1816 and was placed directly under the Storting (Norwegian parliament). The government had no control or influence. The Bank was authorised to issue banknotes that were to serve as legal tender. To ensure stability in the value of money, the banknotes were to be redeemable in silver, although this was not achieved until 1842. -

Regional and Global Financial Safety Nets: the Recent European Experience and Its Implications for Regional Cooperation in Asia

ADBI Working Paper Series REGIONAL AND GLOBAL FINANCIAL SAFETY NETS: THE RECENT EUROPEAN EXPERIENCE AND ITS IMPLICATIONS FOR REGIONAL COOPERATION IN ASIA Zsolt Darvas No. 712 April 2017 Asian Development Bank Institute Zsolt Darvas is senior fellow at Bruegel and senior research Fellow at the Corvinus University of Budapest. The views expressed in this paper are the views of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of ADBI, ADB, its Board of Directors, or the governments they represent. ADBI does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this paper and accepts no responsibility for any consequences of their use. Terminology used may not necessarily be consistent with ADB official terms. Working papers are subject to formal revision and correction before they are finalized and considered published. The Working Paper series is a continuation of the formerly named Discussion Paper series; the numbering of the papers continued without interruption or change. ADBI’s working papers reflect initial ideas on a topic and are posted online for discussion. ADBI encourages readers to post their comments on the main page for each working paper (given in the citation below). Some working papers may develop into other forms of publication. Suggested citation: Darvas, Z. 2017. Regional and Global Financial Safety Nets: The Recent European Experience and Its Implications for Regional Cooperation in Asia. ADBI Working Paper 712. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute. Available: https://www.adb.org/publications/regional-and-global-financial-safety-nets Please contact the authors for information about this paper. Email: [email protected] Paper prepared for the Conference on Global Shocks and the New Global/Regional Financial Architecture, organized by the Asian Development Bank Institute and S. -

Baltic Monetary Regimes in the Xxist Century

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Viksnins, George J. Article — Digitized Version Baltic monetary regimes in the XXIst century Intereconomics Suggested Citation: Viksnins, George J. (2000) : Baltic monetary regimes in the XXIst century, Intereconomics, ISSN 0020-5346, Springer, Heidelberg, Vol. 35, Iss. 5, pp. 213-218 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/40777 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu EU ENLARGEMENT member states, the candidates should expect the dangers of inaction are even greater because the enlargement to be in a state of fluidity. existing member states may use their veto on • Second, the fact that uncertainty cannot be accession of new members to protect their broader interests. -

Relevant Market/ Region Commercial Transaction Rates

Last Updated: 31, May 2021 You can find details about changes to our rates and fees and when they will apply on our Policy Updates Page. You can also view these changes by clicking ‘Legal’ at the bottom of any web-page and then selecting ‘Policy Updates’. Domestic: A transaction occurring when both the sender and receiver are registered with or identified by PayPal as residents of the same market. International: A transaction occurring when the sender and receiver are registered with or identified by PayPal as residents of different markets. Certain markets are grouped together when calculating international transaction rates. For a listing of our groupings, please access our Market/Region Grouping Table. Market Code Table: We may refer to two-letter market codes throughout our fee pages. For a complete listing of PayPal market codes, please access our Market Code Table. Relevant Market/ Region Rates published below apply to PayPal accounts of residents of the following market/region: Market/Region list Taiwan (TW) Commercial Transaction Rates When you buy or sell goods or services, make any other commercial type of transaction, send or receive a charity donation or receive a payment when you “request money” using PayPal, we call that a “commercial transaction”. Receiving international transactions Where sender’s market/region is Rate Outside of Taiwan (TW) Commercial Transactions 4.40% + fixed fee Fixed fee for commercial transactions (based on currency received) Currency Fee Australian dollar 0.30 AUD Brazilian real 0.60 BRL Canadian -

European Commission

EUROPEAN COMMISSION MEMO Brussels, 4 June 2014 The 2014 Convergence Report and Lithuania: frequently asked questions on euro adoption What is the Convergence Report? The Convergence Report forms the basis for the EU Council of Ministers' decision on whether a Member State may join the euro area. The report assesses whether Member States with a derogation1 have achieved a high degree of sustainable economic convergence, in terms of price stability, sound public finances, exchange rate stability and convergence in long-term interest rates. It also assesses the compatibility of their national legislation with Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) rules set out in the Treaty: independence of the national central bank, prohibition of monetary financing, and compatibility with the statutes of the European System of Central Banks (ESCB) and of the European Central Bank (ECB). Convergence Reports are issued every two years or, as was the case for Latvia in 2013, when there is a specific request from a Member State to assess its readiness to join the euro area.The 2014 Convergence Report covers the eight Member States with a derogation: Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Croatia, Lithuania, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Sweden. What are the conclusions of the assessment carried out for Lithuania? The 2014 Convergence Report concludes that Lithuania meets the criteria for adopting the euro. As a consequence, the Commission is proposing that Lithuania adopt the euro on 1 January 2015 and that the Council abrogate the derogation accordingly. This formal decision is expected to be taken by the EU Council of Ministers in the second half of July 2014.