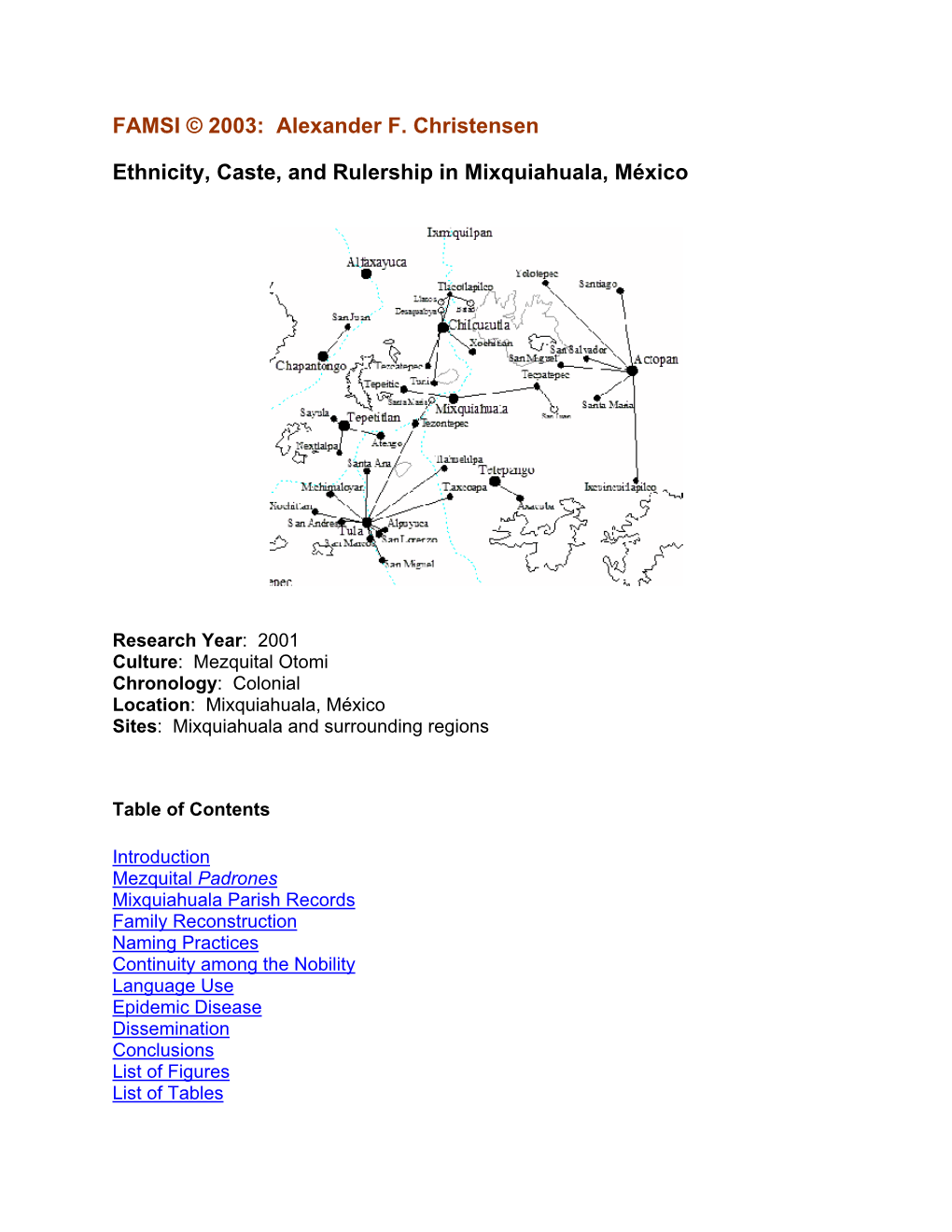

Ethnicity, Caste, and Rulership in Mixquiahuala, México

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Se Anexa Padrón

Secretaría de Desarrollo Económico PROGRAMA DE APOYO: DESARROLLO DE DISTRITOS MINEROS NO. NOMBRE DEL BENEFICIARIO MUNICIPIO 1 Jesús González Carpio Molango 2 Asociación de Extractores e Industrializadores de Cantera de Huichapan A.C. Hichapan 3 Cooperativa de Transportistas El Arenal Zimapán 4 Ánfora International Mineral de La Reforma 5 Ejido Atitalaquia Atitalaquia 6 GEO explotaciones y LM Triturados Atotonilco de Tula 7 MADISA Mineral de La Reforma 8 Espiridión Cruz Estrada Atotonilco de Tula 9 Constructora ARCSA Mineral de La Reforma 10 ROCAFUERTE Huichapan 11 Rafael Jiménez Márquez Ajacuba 12 Grupo J. Noriega y Asociados, S.A. de C.V. Zempoala 13 CEMIX Atotonilco de Tula 14 Explotación y Comercialización de Piedra Calizada Cerro Blanco, S.S.S. Atotonilco de Tula 15 Reviem Energía Zimapán 16 MAPEI México Zimapán 17 Fosforita de México Pacula 18 Cía. Minera La Purísima Zimapán 19 Cía. Minera El Espiritu Zimapán 20 Cía Minera Purisima Zimapán 21 CARINSA Zimapán 22 Calcitas y Marmoles de Tathi Zimapán 23 RIDASA Tula de Allende 24 Bominztha Tula de Allende 25 Cooperativa Juárez Tula de Allende 26 Cementos Cruz Azul Tula de Allende 27 CONDISA Tula de Allende Fecha de actualización: Fecha de validación: 10/Enero/2018 08/Enero/2018 Secretaría de Desarrollo Económico PROGRAMA DE APOYO: DESARROLLO DE DISTRITOS MINEROS NO. NOMBRE DEL BENEFICIARIO MUNICIPIO 28 Coperativa La Unión Tula de Allende 29 Cal El Tigre Tula de Allende 30 Construcciones Jamsa Tula de Allende 31 Canteras Jaramillo Huichapan 32 Productos Mexicanos de Cantera de Hidalgo Huichapan 33 Canteras México Huichapan 34 CANTERESA Huichapan 35 Real Stone Huichapan 36 Comercializadora de Cantera Huichapan Huichapan 37 Morgan Advanced Materials Thermal Ceramics Mineral de La Reforma 38 Vicrila Mineral de La Reforma 39 Cementos Fortaleza Planta Tula Atotonilco de Tula 40 Cía. -

Concluye El 1Er Periodo Ordinario Del 3Er Año De Ejercicio De La LXIV Legislatura

Pachuca, Hgo., a 29 de diciembre de 2020. Concluye el 1er periodo ordinario del 3er año de ejercicio de la LXIV Legislatura Este martes 29 de diciembre, integrantes de la LXIV Legislatura del Congreso del Estado de Hidalgo, previo a clausurar los trabajos del Primer Periodo Ordinario de Sesiones del Tercer Año de Ejercicio, sesionaron para aprobar 82 de 84 propuestas de Leyes de Ingresos municipales para igual número de ayuntamientos que serán vigentes durante el Ejercicio Fiscal 2021. Los 82 ayuntamientos a los que les fueron autorizados, son Acatlán, Acaxochitlán, Actopan, Agua Blanca, Ajacuba, Alfajayucan, Almoloya, Apan, Atitalaquia, Atlapexco, Atotonilco de Tula, Atotonilco el Grande, Calnali, Cardonal, Chapantongo, Chapulhuacán, Chilcuautla, Cuautepec de Hinojosa, El Arenal, Eloxochitlán, Emiliano Zapata, Epazoyucan, Francisco I. Madero y Huautla. Asimismo, Huasca de Ocampo, Huazalingo, Huehuetla, Huejutla, Huichapan, Ixmiquilpan, Jacala, Jaltocan, Juárez Hidalgo, La Misión, Lolotla, Metepec, Metztitlán, Mineral de la Reforma, Mineral del Chico, Mineral del Monte, Mixquiahuala, Molango, Nicolás Flores, Nopala, Omitlán de Juárez, Pachuca de Soto, Pacula, Pisaflores, Progreso de Obregón, San Salvador, San Agustín Metzquititlán, San Agustín Tlaxiaca y San Bartolo Tutotepec. También, San Felipe Orizatlán, Santiago de Anaya, Tasquillo, Tecozautla, Tenango de Doria, Tepeapulco, Tepehuacán de Guerrero, Tepeji del Río, Tepetitlán, Tetepango, Tezontepec de Aldama, Tianguistengo, Tizayuca, Tlahuelilpan, Tlahuiltepa, Tlanalapa, Tlanchinol, Tlaxcoapan, Tolcayuca, Tula de Allende, Tulancingo de Bravo, Villa de Tezontepec, Xochiatipan, Xochicoatlán, Yahualica, Zacualtipán de Ángeles, Zapotlán de Juárez, Zempoala y Zimapán. Se explicó que las iniciativas de Leyes de Ingresos que se dictaminan, son congruentes con lo establecido a la Ley de Hacienda para los Municipios del Estado de Hidalgo, al señalar el ámbito y la vigencia de su aplicación, los conceptos de ingresos que constituyen la hacienda pública de los Municipios, así como las reglas que regirán su operación. -

Programa De Fomento Agropecuario Delegación

DELEGACIÓN ESTATAL HIDALGO SUBDELEGACIÓN AGROPECURIA PROGRAMA DE FOMENTO AGROPECUARIO LISTADO DE BENEFICIARIOS DEL COMPONENTE PIMAF ALTA PRODUCTIVIDAD UNIDAD DE NO. FOLIO ESTATAL DISTRITO CADER MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD BENEFICIO DESCRIPCION CANTIDAD MEDIDA 1 HG1400014436 HUICHAPAN HUICHAPAN NOPALA DE VILLAGRAN BATHA Y BARRIOS SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. 433.60 2 HG1400003250 MIXQUIAHUALA ALFAJAYUCAN ALFAJAYUCAN LA VEGA SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. 4.00 3 HG1400014773 ZACUALTIPAN METZTITLÁN METZTITLÁN SAN JUAN METZTITLÁN SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. 20.00 4 HG1400014784 ZACUALTIPAN METZTITLÁN METZTITLÁN SAN JUAN METZTITLÁN SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. 4.02 5 HG1400004599 MIXQUIAHUALA ALFAJAYUCAN ALFAJAYUCAN MADHO CORRALES SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. 3.00 6 HG1400003733 MIXQUIAHUALA ALFAJAYUCAN ALFAJAYUCAN YONTHE GRANDE SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. 4.00 7 HG1400004942 MIXQUIAHUALA ALFAJAYUCAN ALFAJAYUCAN SANTA MARÍA LA PALMA SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. 1.00 8 HG1400005711 MIXQUIAHUALA ALFAJAYUCAN ALFAJAYUCAN PRIMERA MANZANA DOSDHA SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. 1.00 9 HG1400004970 MIXQUIAHUALA ALFAJAYUCAN ALFAJAYUCAN TERCERA MANZANA SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. 7.00 10 HG1400004208 MIXQUIAHUALA ALFAJAYUCAN ALFAJAYUCAN EL BERMEJO SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. 5.00 11 HG1400004640 MIXQUIAHUALA ALFAJAYUCAN ALFAJAYUCAN XAMAGE SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. 1.00 12 HG1400005043 MIXQUIAHUALA ALFAJAYUCAN ALFAJAYUCAN YONTHE GRANDE SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. 2.00 13 HG1400003742 MIXQUIAHUALA ALFAJAYUCAN ALFAJAYUCAN XAMAGE SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. 2.00 14 HG1400014757 ZACUALTIPAN METZTITLÁN METZTITLÁN ATZOLCINTLA SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. 1.08 15 HG1400005744 MIXQUIAHUALA ALFAJAYUCAN ALFAJAYUCAN MADHO CORRALES SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. 3.00 16 HG1400005254 MIXQUIAHUALA ALFAJAYUCAN ALFAJAYUCAN NAXTHEY SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. 4.00 17 HG1400014867 ZACUALTIPAN METZTITLÁN METZTITLÁN SAN JUAN METZTITLÁN SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. 9.50 18 HG1400005061 MIXQUIAHUALA ALFAJAYUCAN ALFAJAYUCAN EL DOYDHE SEMILLA SEMILLA MEJORADA HA. -

Delegación En El Estado De Hidalgo Subdelegación Agropecuaria Jefatura Del Programa De Fomento a La Agricultura Pa

DELEGACIÓN EN EL ESTADO DE HIDALGO SUBDELEGACIÓN AGROPECUARIA JEFATURA DEL PROGRAMA DE FOMENTO A LA AGRICULTURA PADRÓN DE BENEFICIARIOS DEL COMPONENTE REPOBLAMIENTO Y RECRIA PECUARIA-INFRAESTRUCTURA Y EQUIPO EN LAS UPP MONTO DE NO. ESTADO FOLIO ESTATAL REGION DEL PAIS DISTRITO CADER MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD BENEFICIO DESCRIPCIÓN TIPO DE PERSONA APOYO ($) 1 HIDALGO HG1600005161 centro HUICHAPAN HUICHAPAN TECOZAUTLA SAN ANTONIO INFRAESTRUCTURA Y EQUIPO DE LAS UPP EQUIPO 280,350.00 FÍSICA 2 HIDALGO HG1600005217 centro TULANCINGO SAN BARTOLO TUTOTEPEC METEPEC EL VESUBIO INFRAESTRUCTURA Y EQUIPO DE LAS UPP INFRAESTRUCTURA 241,455.00 FÍSICA 3 HIDALGO HG1600005232 centro TULANCINGO SAN BARTOLO TUTOTEPEC METEPEC LAS TROJAS INFRAESTRUCTURA 238,994.00 FÍSICA 4 HIDALGO HG1600005388 centro TULANCINGO TULANCINGO SINGUILUCAN SANTA ANA CHICHICUAUTLA INFRAESTRUCTURA Y EQUIPO DE LAS UPP INFRAESTRUCTURA 237,899.20 FÍSICA 5 HIDALGO HG1600005403 centro TULANCINGO TULANCINGO SINGUILUCAN SANTA ANA CHICHICUAUTLA INFRAESTRUCTURA Y EQUIPO DE LAS UPP INFRAESTRUCTURA 237,899.20 FÍSICA 6 HIDALGO HG1600005422 centro HUICHAPAN HUICHAPAN TECOZAUTLA EL SALTO INFRAESTRUCTURA Y EQUIPO DE LAS UPP EQUIPO 196,000.00 FÍSICA 7 HIDALGO HG1600005434 centro HUICHAPAN HUICHAPAN TECOZAUTLA EL SALTO INFRAESTRUCTURA Y EQUIPO DE LAS UPP INFRAESTRUCTURA 18,900.00 FÍSICA 8 HIDALGO HG1600005462 centro MIXQUIAHUALA TULA TULA DE ALLENDE SANTA ANA AHUEHUEPAN INFRAESTRUCTURA Y EQUIPO DE LAS UPP EQUIPO 213,689.70 FÍSICA 9 HIDALGO HG1600005481 centro TULANCINGO TULANCINGO SINGUILUCAN EL VENADO -

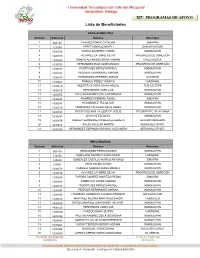

XIV. PROGRAMAS DE APOYO Lista De Beneficiarios

Universidad Tecnológica del Valle del Mezquital Ixmiquilpan, Hidalgo. XIV. PROGRAMAS DE APOYO Lista de Beneficiarios BECA ALIMENTICIA Número Matrícula Nombre Municipio 1 083137 CHAVEZ PONCE CATALINA ZIMAPÁN 2 123069 PEREZ IGNACIO NAYELI SAN SALVADOR 3 1330186 VIXTHA QUITERIO YADIRA IXMIQUILPAN 4 1330189 ÁLVAREZ LATORRE SILVIA PROGRESO DE OBREGÓN 5 1330455 RAMOS ALVARADO ERIKA YAZMIN CHILCUAUTLA 6 1330573 HERNÁNDEZ RUIZ JOSÉ MANUEL PROGRESO DE OBREGÓN 7 1330733 RODRÍGUEZ PÉREZ MARISOL IXMIQUILPAN 8 1330741 PEDRAZA HERNÁNDEZ MARINA IXMIQUILPAN 9 1330817 HERNANDEZ HERRERA MIRIAM ACTOPAN 10 1330867 RÓMULO PÉREZ YESSICA CARDONAL 11 1430142 MONTER OLVERA JUAN CARLOS TLAHUILTEPA 12 1430726 HERNANDEZ JOSE LUIS IXMIQUILPAN 13 1430856 FALCON RAMIREZ ZEILA GEORGINA IXMIQUILPAN 14 1530453 RAMÍREZ FERRERA ÁNGEL ZIMAPÁN 15 1530584 HERNÁNDEZ TREJO JAIR IXMIQUILPAN 16 1530719 YERBAFRIA CALLEJAS DALIA HASEL IXMIQUILPAN 17 1630191 BECIEZ ESCAMILLA JOSÉ DE JESÚS TEZONTEPEC DE ALDAMA 18 1630681 ARROYO EZEQUIEL IXMIQUILPAN 19 1630876 JUÁREZ HERNÁNDEZ PAMELA ELIZABETH ÁLVARO OBREGÓN 20 1630917 SALAS AGUILAR MARTÍN NEZAHUALCÓYOTL 21 1630918 HERNÁNDEZ ESPINOSA ROXANA ALEJANDRA NEZAHUALCÓYOTL BECA EQUIDAD Número Matrícula Nombre Municipio 1 053118 HERNANDEZ PEREZ MOISES IXMIQUILPAN 2 113250 MORGADO RAMIREZ GERALDINNE CARDONAL 3 123040 GONZALEZ CASTILLO MARCO ANTONIO ZIMAPÁN 4 123601 PEÑA PALMA CESAR IXMIQUILPAN 5 1330173 CAZUELA GABRIEL DIANA MARELY IXMIQUILPAN 6 1330189 ÁLVAREZ LATORRE SILVIA PROGRESO DE OBREGÓN 7 1330495 TORRES RAMÍREZ MARITZA PIEDAD ZIMAPÁN -

Secretaría De Educación Pública De Hidalgo Subdirección De Educación Básica Dirección De Servicios Regionales

SECRETARÍA DE EDUCACIÓN PÚBLICA DE HIDALGO SUBDIRECCIÓN DE EDUCACIÓN BÁSICA DIRECCIÓN DE SERVICIOS REGIONALES DIRECTORIO DE ALMACENES DE SERVICIOS REGIONALES SUBDIRECCIÓ CT TELÉFONO TELÉFONO DIRECCIÓN DE ALMACEN DE LIBROS DIRECCIÓN DE ALMACEN DE ÚTILES NOMBRE RESPONSABLE TELÉFONO No. SUBDIRECTOR CORREO DIRECCIÓN DE OFICINA N REGIONAL OFICINA CELULAR DE TEXTO ESCOLARES ALMACEN CELULAR CARRETERA MÉXICO - TAMPICO (VÍA CORTA), CARRETERA MÉXICO - TAMPICO (VÍA CORTA), PROFR. DAGOBERTO PÉREZ SILVA C. PABLO MARIA ANAYA ESQ. BLVD. ADOLFO HUEJUTLA CHALAHUIYAPA KM. 221 PARQUE HUEJUTLA CHALAHUIYAPA KM. 221 PARQUE 7712203895 PROFR. HERNÁN CORTES 1 HUEJUTLA 13ADG0002R MTRA. ZORAYA INES RIVERA LÓPEZ 01 789 896 3736 771 221 3574 [email protected] LÓPEZ MATEOS S/N, COL. AVIACIÓN CIVÍL C.P. INDUSTRIAL, COL. PARQUE DE POBLAMIENTO, INDUSTRIAL, COL. PARQUE DE POBLAMIENTO, 7712098281 BAUTISTA 43000, HUEJUTLA DE REYES, HGO. HUEJUTLA DE REYES HGO. C.P.43000 HUEJUTLA DE REYES HGO. C.P.43000 7711789560 PROFRA. GRACIELA CISNEROS PUERTA 1 PUERTA 1 CARR. IXMIQUILPAN - ORIZABITA S/N. LOC. CARR. IXMIQUILPAN - ORIZABITA S/N. LOC. LOS CARR. IXMIQUILPAN - ORIZABA S/N. LOC. LOS PROFRA. MA. DEL CARMEN CRUZ 2 IXMIQUILPAN 13ADG0003Q PROFR. CRISTINO URIBE CANO 01 759 723 6199 771 220 9204 [email protected] LOS REMEDIOS C.P. 42300, IXMIQUILPAN 7721028913 REMEDIOS C.P. 42313, IXMIQUILPAN HGO. REMEDIOS C.P. 42313, IXMIQUILPAN HGO. HERNÁNDEZ HGO. AV. MIGUEL HIDALGO NORTE 41 EL LLANO 5574400528 BLVD. TULA - ITURBE 400 COL. ITURBE, C.P. BLVD. TULA - ITURBE 400 COL. ITURBE, C.P. 3 TULA 13ADG0004P PROFR. OCTAVIANO ÁNGELES LÓPEZ 01 773 732 6031 [email protected] 1ra. -

Complementario 4. Aportaciones Por Fondo Y Municipio

Presupuesto de Egresos del Estado de Hidalgo Ejercicio Fiscal 2019 Aportaciones por fondo y municipio Complementario 4 Fondo de Fondo de Aportaciones a la Fortalecimiento Municipio Monto Presupuestado Infraestructura Municipal Acatlán 28,021,607 15,136,756 12,884,851 Acaxochitlán 77,633,477 50,831,469 26,802,008 Actopan 53,199,868 18,649,438 34,550,430 Agua Blanca de Iturbide 17,318,162 11,736,604 5,581,558 Ajacuba 17,314,546 6,097,550 11,216,996 Alfajayucan 36,807,704 24,358,798 12,448,906 Almoloya 16,824,856 9,226,443 7,598,413 Apan 49,993,644 22,700,586 27,293,058 Atitalaquia 23,229,041 5,054,691 18,174,350 Atlapexco 48,345,242 36,159,617 12,185,625 Atotonilco de Tula 30,316,443 6,704,421 23,612,022 Atotonilco el Grande 36,029,572 19,232,855 16,796,717 Calnali 39,737,384 29,228,798 10,508,586 Cardonal 30,057,088 18,823,560 11,233,528 Cuautepec de Hinojosa 77,334,075 41,637,455 35,696,620 Chapantongo 24,926,386 16,483,637 8,442,749 Chapulhuacán 54,528,100 39,857,224 14,670,876 Chilcuautla 28,872,727 17,748,185 11,124,542 El Arenal 20,664,580 9,149,403 11,515,177 Eloxochitlán 7,251,891 5,618,936 1,632,955 Emiliano Zapata 12,838,412 3,761,340 9,077,072 Epazoyucan 12,785,838 3,789,587 8,996,251 Francisco I. -

Pachuca De Soto, Hidalgo, a 19 De Junio De 2008

Pachuca de Soto, Hidalgo, a 24 de Octubre de 2016. Apreciable solicitante Presente. En atención y seguimiento a la solicitud de información identificada con el folio número 00232516, realizada por Usted ante la Unidad de Información Pública Gubernamental del Poder Ejecutivo del Estado de Hidalgo, mediante la cual requiere: “¿Cuántos cuerpos sin vida han sido localizados en municipios del estado de Hidalgo desde enero de 2011 hasta agosto de 2016? ¿Cuántos de éstos presentaron signos de tortura? ¿Cuántos fueron hallados en bolsas de plástico, canales de aguas de aguas negras, carreteras o parajes? ¿Cuántos estaban desmembrados? La información, además, debe desagregarse por sexo de las víctimas, años en los que ocurrieron los casos y municipios.” Con la finalidad de dar cumplimiento a lo solicitado, de conformidad con los Artículos 5, Fracción VIII, incisos b) y d), 56 Fracción I, 64, 67 de la Ley de Transparencia y Acceso a la Información Pública Gubernamental para el Estado de Hidalgo y 4 de su Reglamento, la Unidad de Información Pública Gubernamental de éste sujeto obligado se permite hacer de su conocimiento lo referido por la(s) Unidad (es) Administrativa(s) responsable(s) de la información: AVERIGUACIONES PREVIAS 2011 CUERPOS SIN VIDA 61 MUNICIPIOS FRANCISCO I MADERO, EL ARENAL, ACTOPAN, SAN SALVADOR, CD. SAHAGUN, HUEJUTLA, SAN FELIPE ORIZATLAN, TLANCHINOL, IXMIQUILPAN, JACALA, METZTITLAN, LOLOTLA, MIXQUIAHUALA, PACHUCA, APAN, TEPEHUACAN, TIZAYUCA, TULA, AJACUBA, TEPEJI, TENANGO, SAN BARTOLO, CUAUTEPEC, SANTIALGO TULANTEPEC, ACAXOHITLA, -

Porcentaje De La Población Según El Tipo De Carencia Social, Por Municipio Medición De La Pobreza, Hidalgo, 2010

Medición de la pobreza, Hidalgo, 2010 Porcentaje de la población según el tipo de carencia social, por municipio Clave de Entidad federativa Clave de Municipio Población Carencia por entidad municipio calidad y espacios de la vivienda 13 Hidalgo 13001 Acatlán 18,816 9.2 13 Hidalgo 13002 Acaxochitlán 32,389 29.7 13 Hidalgo 13003 Actopan 56,603 10.0 13 Hidalgo 13004 Agua Blanca de Iturbide 7,927 15.1 13 Hidalgo 13005 Ajacuba 15,097 6.1 13 Hidalgo 13006 Alfajayucan 16,397 10.6 13 Hidalgo 13007 Almoloya 10,990 14.6 13 Hidalgo 13008 Apan 38,635 11.7 13 Hidalgo 13009 El Arenal 19,479 16.4 13 Hidalgo 13010 Atitalaquia 31,477 8.4 13 Hidalgo 13011 Atlapexco 16,789 30.8 13 Hidalgo 13012 Atotonilco el Grande 31,226 7.8 13 Hidalgo 13013 Atotonilco de Tula 34, 918 414.1 13 Hidalgo 13014 Calnali 14,922 22.5 13 Hidalgo 13015 Cardonal 17,082 12.3 13 Hidalgo 13016 Cuautepec de Hinojosa 51,572 17.9 13 Hidalgo 13017 Chapantongo 11,691 9.2 13 Hidalgo 13018 Chapulhuacán 20,946 20.8 13 Hidalgo 13019 Chilcuautla 15,154 10.1 13 Hidalgo 13020 Eloxochitlán 2,403 15.5 13 Hidalgo 13021 Emiliano Zapata 14,346 7.5 13 Hidalgo 13022 Epazoyucan 14,924 8.7 13 Hidalgo 13023 Francisco I. Madero 32,377 7.1 13 Hidalgo 13024 Huasca de Ocampo 15,716 9.7 13 Hidalgo 13025 Huautla 20,820 40.2 13 Hidalgo 13026 Huazalingo 10,390 42.5 13 Hidalgo 13027 Huehuetla 20,084 26.9 13 Hidalgo 13028 Huejutla de Reyes 119,281 34.0 13 Hidalgo 13029 Huichapan 47,013 8.8 13 Hidalgo 13030 Ixmiquilpan 86,555 11.7 Medición de la pobreza, Hidalgo, 2010 Porcentaje de la población según el tipo de carencia -

ENTIDAD MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD LONG LAT Hidalgo Atotonilco De

ENTIDAD MUNICIPIO LOCALIDAD LONG LAT Hidalgo Atotonilco de Tula SAN JOSÉ ACOCULCO 991804 195809 Hidalgo Atotonilco de Tula EL PEDREGAL 991407 195609 Hidalgo Atotonilco de Tula SAN ANTONIO 991713 195714 Hidalgo Atotonilco de Tula PRADERAS DEL POTRERO 991349 195305 Hidalgo Atotonilco de Tula BATHA 991535 195851 Hidalgo Atotonilco de Tula LA SIERRITA (LA PRESA DEL TEJOCOTE) 991600 195814 Hidalgo Atotonilco de Tula EL PORTAL 991754 195659 Hidalgo Atotonilco de Tula SANTA CRUZ DEL TEZONTLE 991402 195642 Hidalgo Atotonilco de Tula EL VENADO 991759 195655 Hidalgo Atotonilco de Tula PASEOS DE LA PRADERA 991417 195328 Hidalgo Chapantongo SANTA MARÍA AMEALCO 993257 201414 Hidalgo Chapantongo EL CAPULÍN 993003 201049 Hidalgo Chapantongo JUCHITLÁN 992832 201146 Hidalgo Chapantongo SAN JOSÉ EL MARQUÉS (ESCANDÓN) 993347 201231 Hidalgo Chapantongo SAN ISIDRO 992906 201047 Hidalgo Chapantongo EL CAMARÓN 993042 201141 Hidalgo Chapantongo EL COLORADO (CERRO COLORADO) 992855 201033 Hidalgo Chapantongo RANCHO NUEVO 992936 201204 Hidalgo Chapantongo COLONIA FÉLIX OLVERA 993526 201421 Hidalgo Chapantongo EX-HACIENDA EL MARQUÉS 993218 201256 Hidalgo Chapantongo LA NORIA (EL PLAN) 993405 201429 Hidalgo Nopala de Villagrán NOPALA 993843 201503 Hidalgo Nopala de Villagrán BATHA Y BARRIOS 994322 201437 Hidalgo Nopala de Villagrán EL BORBOLLÓN 994413 201314 Hidalgo Nopala de Villagrán EL CAPULÍN DE ARAGÓN 993653 201202 Hidalgo Nopala de Villagrán EL FRESNO (CASAS VIEJAS) 994720 201417 Hidalgo Nopala de Villagrán EL CEDAZO 994057 201423 Hidalgo Nopala de Villagrán -

Anexo B. Índices De Intensidad Migratoria México-Estados Unidos Por Entidad Federativa Y Municipio

Anexo B. Índices de intensidad migratoria México-Estados Unidos por entidad federativa y municipio Anexo B. Índices de intensidad migratoria México-Estados Unidos por entidad federativa y municipio Mapa B.1. Aguascalientes: Grado de intensidad migratoria por municipio, 2010 Simbología Grado de intensidad No. de Zacatecas migratoria municipios Muy alto 2 Alto 3 Medio 5 Bajo 1 Muy bajo -- Nulo -- Porcentaje de viviendas en los municipios, según grado de intensidad migratoria 4.9% 6.5% 18.3% 70.2% Medidas descriptivas por indicador Valor Indicador Municipal Estatal asociado a: Min Max Remesas 4.8 3.3 19.7 Emigrantes 2.6 1.6 10.3 Migrantes círculares 1.6 0.9 6.9 Migrantes de retorno 3.1 1.9 11.7 Jalisco 071421Km. Fuente: Estimaciones del CONAPO con base en el INEGI, muestra del diez por ciento del Censo de Población y Vivienda 2010. 67 Consejo Nacional de Población Cuadro B.1. Aguascalientes: Total de viviendas, indicadores sobre migración a Estados Unidos, índice y grado de intensidad migratoria, y lugar que ocupa en los contextos estatal y nacional, por municipio, 2010 Índice de Clave % Viviendas con % Viviendas % Viviendas Lugar que intensidad Lugar que de la Clave del % Viviendas emigrantes a con migrantes con migrantes Índice de Grado de ocupa Entidad federativa/ Total de migratoria ocupa en el entidad munici- que reciben Estados Unidos circulares del de retorno del intensidad intensidad en el Municipio viviendas1 reescalado contexto federa- pio remesas del quinquenio quinquenio quinquenio migratoria migratoria contexto de 0 a estatal3 -

Chichimecas of War.Pdf

Chichimecas of War Edit Regresión Magazine Winter 2017 EDITORIAL This compilation is a study concerning the fiercest and most savage natives of Northern Mesoamerica. The ancient hunter-gatherer nomads, called “Chichimecas,” resisted and defended with great daring their simple ways of life, their beliefs, and their environment,. They decided to kill or die for that which they considered part of themselves, in a war declared against all that was alien to them. We remember them in this modern epoch not only in order to have a historical reference of their conflict, but also as evidence of how, due to the simple fact of our criticism of technology, sharpening our claws to attack this system and willing to return to our roots, we are reliving this war. Just like our ancestors, we are reviving this internal fire that compels us to defend ourselves and defend all that is Wild. Many conclusions can be taken from this study. The most important of these is to continue the war against the artificiality of this civilization, a war against the technological system that rejects its values and vices. Above all, it is a war for the extremist defense of wild nature. Axkan kema tehuatl nehuatl! Between Chichimecas and Teochichimecas According to the official history, in 1519, the Spanish arrived in what is now known as “Mexico”. It only took three years for the great Aztec (or Mexica) empire and its emblematic city, Tenochtitlán, to fall under the European yoke. During the consolidation of peoples and cities in Mexica territory, the conquistadors’ influence increasingly extended from the center of the country to Michoacán and Jalisco.