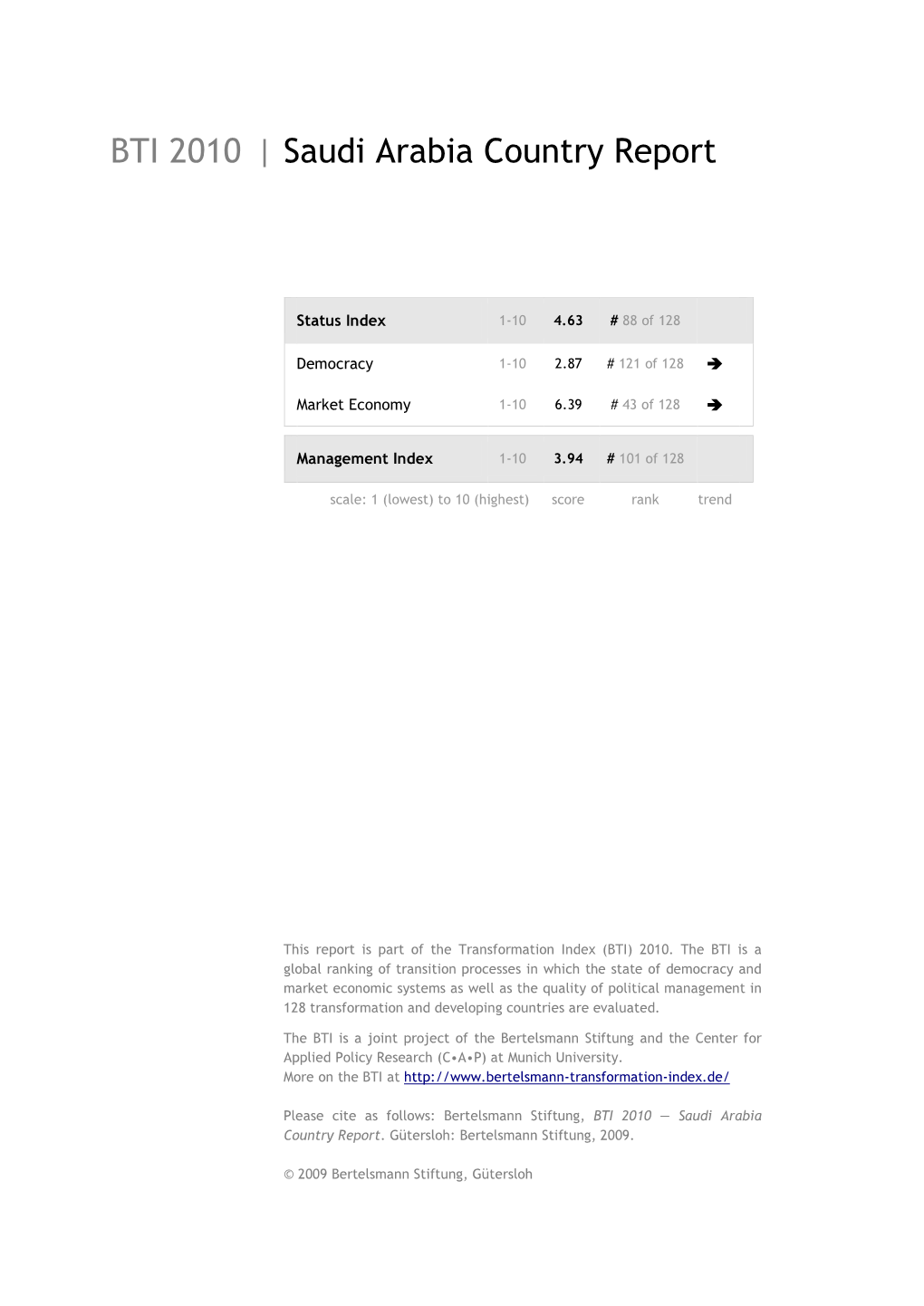

Saudi Arabia Country Report BTI 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNEMPLOYMENT in SAUDI ARABIA: ASSESSMENT of the SAUDIZATION PROGRAM and the IMPERATIVES LEADING to YOUTH UNEMPLOYMENT a Thesis Submitted By

The American University in Cairo School of Global Affairs and Public Policy UNEMPLOYMENT IN SAUDI ARABIA: ASSESSMENT OF THE SAUDIZATION PROGRAM AND THE IMPERATIVES LEADING TO YOUTH UNEMPLOYMENT A Thesis Submitted to the Department of Public Policy and Administration in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Masters in Public Policy and Administration By Saud Abdulaziz Kabli Under the Supervision of Dr. Hamid Ali December 2014 The American University in Cairo School of Global Affairs and Public Policy UNEMPLOYMENT IN SAUDI ARABIA: ASSESSMENT OF THE SAUDIZATION PROGRAM AND THE IMPERATIVES LEADING TO YOUTH UNEMPLOYMENT A Thesis Submitted by Saud Abdulaziz Kabli to the Department of Public Policy and Administration November 2014 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Masters in Public Policy and Administration has been approved by the Committee composed of Professor Hamid Ali _______________________________ Thesis Supervisor American University in Cairo Date ____________________ Professor Bahgat Korany _______________________________ Thesis First Reader American University in Cairo Date ____________________ Professor Ghada Barsoum_______________________________ Thesis Second Reader American University in Cairo Date ___________________ Professor Hamid Ali___________________________________ Public Policy and Administration Department Chair Date ____________________ Ambassador Nabil Fahmy _______________________________ Dean of GAPP Date ____________________ ii Acknowledgement I am extremely grateful to my supervisor Prof. Hamid Ali, Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Public Policy and Administration, for the support and guidance he has provided me throughout the course of my thesis research. I am grateful as well to my thesis readers, Prof. Bahgat Korany, Professor in the Department of Political Science and the Director of the AUC Forum, and Prof. -

Security Council Distr.: General 27 January 2020

United Nations S/2020/70 Security Council Distr.: General 27 January 2020 Original: English Letter dated 27 January 2020 from the Panel of Experts on Yemen addressed to the President of the Security Council The members of the Panel of Experts on Yemen have the honour to transmit herewith the final report of the Panel, prepared in accordance with paragraph 6 of resolution 2456 (2019). The report was provided to the Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 2140 (2014) on 27 December 2019 and was considered by the Committee on 10 January 2020. We would appreciate it if the present letter and the report were brought to the attention of the members of the Security Council and issued as a document of the Council. (Signed) Dakshinie Ruwanthika Gunaratne Coordinator Panel of Experts on Yemen (Signed) Ahmed Himmiche Expert (Signed) Henry Thompson Expert (Signed) Marie-Louise Tougas Expert (Signed) Wolf-Christian Paes Expert 19-22391 (E) 070220 *1922391* S/2020/70 Final report of the Panel of Experts on Yemen Summary After more than five years of conflict, the humanitarian crisis in Yemen continues. The country’s many conflicts are interconnected and can no longer be separated by clear divisions between external and internal actors and events. Throughout 2019, the Houthis and the Government of Yemen made little headway towards either a political settlement or a conclusive military victory. In a continuation from 2018, the belligerents continued to practice economic warfare: using economic obstruction and financial tools as weapons to starve opponents of funds or materials. Profiteering from the conflict is endemic. -

(Nitaqat) in Saudi Arabia and the Condition of Filipino Migrant Workers

Journal of Identity and Migration Studies Volume 8, number 2, 2014 Nationalization Scheme (Nitaqat) in Saudi Arabia and the Condition of Filipino Migrant Workers Henelito A. SEVILLA, Jr.1 Abstract. The Philippines is one of few countries in the developing world that heavily relied on exporting its laborers to sustain its economic growth. Despite attempts by previous administrations to minimize sending Filipino workers abroad by improving working condition at home so that working abroad would no longer be compulsory but optional, many Filipinos continue to leave the country hoping to alleviate their families from poverty. This idea of working abroad has several implications for migrant workers especially in regions where labor policies are not clearly laid down and that rights and welfare of migrant workers are not protected. This paper seeks to elucidate the conditions of Overseas Filipinos Workers (OFWs) in Saudi Arabia which strictly implemented “Saudization”2 policy since 2011. In particular, the paper tries to address the following questions: What does “Saudization” (nitaqat) mean from Filipinos’ perspectives?; Who are affected by this policy and Why have OFWs been affected by such policy?; How did undocumented or illegal OFWs survive in previous years?; What policies they have implemented to counter it? This paper is centered on its main thesis that Saudi Nationalization policy, which is centered on solving socio-economic problems facing the young and unemployed population in several Gulf countries, has been the driver for these governments to strictly implement such a law and that many migrant workers including Filipinos working on specific areas together with undocumented ones are gravely affected. -

The Quest for Increased Saudization: Labor Market Outcomes and the Shadow Price of Workforce Nationalization Policies

The Quest for Increased Saudization: Labor Market Outcomes and the Shadow Price of Workforce Nationalization Policies Michael Lopesciolo, Daniela Muhaj, and Carolina Pan CID Research Fellow and Graduate Student Working Paper No. 132 July 2021 © Copyright 2021 Lopesciolo, Michael; Muhaj, Daniela; Pan, Carolina; and the President and Fellows of Harvard College Acknowledgments This paper was written in support of the Economic Diversification & Growth Diagnostics in Saudi Arabia project at the Center for International Development’s Growth Lab at Harvard University. This paper benefited from the feedback of Ricardo Hausmann, Tim Cheston, Semiray Kasoolu, Farah Hani, Matte Hartog, Ricardo Villasmil, Can Soylu, and Shreyas Matha. The authors are grateful to the Labor Market Program in Public Policy General Department at the Ministry of Economy and Planning for their valuable comments. Abstract Few countries have embraced active labor market policies to the same extent as Saudi Arabia. In the aftermath of the Arab Spring, the imperative of increasing Saudi employment became paramount. The country faced one of the highest youth unemployment rates in the world while over 80 percent of its private sector consisted of foreign labor. Since 2011, a wave of employment nationalization efforts has been mainly implemented through a comprehensive and strictly enforced industry and firm specific quota system known as Nitaqat. This paper assesses the employment gains as well as the costs and unintended consequences resulting from Nitaqat and related policies between 2011 and 2017. We find that while job nationalization policies generated significant initial gains in Saudi employment and labor force participation, the effects were heterogeneous across workers, firms and sectors. -

Saudi Arabia 2016 Human Rights Report

SAUDI ARABIA 2016 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is a monarchy ruled by King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, who is both head of state and head of government. The government bases its legitimacy on its interpretation of sharia (Islamic law) and the 1992 Basic Law, which specifies that the rulers of the country shall be male descendants of the founder, King Abdulaziz bin Abdulrahman Al Saud. The Basic Law sets out the system of governance, rights of citizens, and powers and duties of the government, and it provides that the Quran and Sunna (the traditions of the Prophet Muhammad) serve as the country’s constitution. In December 2015 the country held municipal elections on a nonparty basis for two-thirds of the 3,159 seats on the 284 municipal councils around the country. Independent polling station observers identified no significant irregularities with the election. For the first time, women were allowed to vote and run as candidates. Civilian authorities generally maintained effective control over the security forces. The most important human rights problems reported included citizens’ lack of the ability and legal means to choose their government; restrictions on universal rights, such as freedom of expression, including on the internet, and the freedoms of assembly, association, movement, and religion; and pervasive gender discrimination and lack of equal rights that affected most aspects of women’s lives. Other human rights problems reported included: a lack of judicial independence and transparency that manifested itself in denial of due process and arbitrary arrest and detention; a lack of equal rights for children and noncitizen workers; abuses of detainees; overcrowding in prisons and detention centers; investigating, detaining, prosecuting, and sentencing lawyers, human rights activists, and antigovernment reformists; holding political prisoners; arbitrary interference with privacy, home, and correspondence; and a lack of equal rights for children and noncitizen workers. -

The Feasibility of Saudization: Costs and Benefits to Saudi Arabia

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2003 The feasibility of Saudization: Costs and benefits ot Saudi Arabia Sulaiman Abdulrahman Al-Khuzaim Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the International Business Commons Recommended Citation Al-Khuzaim, Sulaiman Abdulrahman, "The feasibility of Saudization: Costs and benefits ot Saudi Arabia" (2003). Theses Digitization Project. 2193. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/2193 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FEASIBILITY OF SAUDIZATION: COSTS AND BENEFITS TO SAUDI ARABIA A Project Presented to the I Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino i i I In Partial Fulfillment I of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Public Administration by Sulaiman Abdulrahman Al-Khuzaim March 2003 i I I I THE FEASIBILITY OF SAUDIZATION: COSTS AND BENEFITS TO SAUDI ARABIA i A Projeqt Presented to the I Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by I Sulaiman Abdulrahman Al-Khuzaim Date I I I ABSTRACT Following the discovery of oil in Saudi Arabia, five year plans for economic development and modernization followed. Foreign workers were needed to provide the skills required for the projects designed by the plans. Although most of the major projects have been completed, a high percentage of foreign workers continue to be employed i in the Kingdom. -

Doing Business Guide 2021: Understanding Saudi Arabia's Tax Position

Doing business guide 2021 Understanding Saudi Arabia’s tax position Doing business guide | Understanding Saudi Arabia’s tax position Equam ipsamen 01 Impos is enditio rendae acea 02 Debisinulpa sequidempos 03 Imo verunt illia 04 Asus eserciamus 05 Desequidellor ad et 06 Ivolupta dolor sundus et rem 07 Limporpos eum sequas as 08 Ocomniendae dit ulparcia dolori 09 Aquia voluptas seque 10 Dolorit ellaborem rest mi 11 Foccaes in nulpa arumquis 12 02 Doing business guide | Understanding Saudi Arabia’s tax position Contents 04 About the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia 06 Market overview 08 Industries of opportunity 10 Entering the market 03 Doing business guide | Understanding Saudi Arabia’s tax position About the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia The Kingdom" of Saudi A country located in the Arabian Peninsula, Throughout this guide, we have provided the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA, Saudi our comments with respect to KSA, unless Arabia is the largest Arabia or The Kingdom) is the largest oil- noted otherwise. oil-producing country producing country in the world. in the world Government type Monarchy " Population (2019) 34.2 million GDP (2019) US$ 793 billion GDP growth (2019) 0.33% Inflation (2019) -2.09% Labor force (2019) 14.38 million Crude oil production, petroleum refining, basic petrochemicals, ammonia, Key industries industrial gases, sodium hydroxide (caustic soda), cement, fertilizer, plastics, metals, commercial ship repair, commercial aircraft repair, construction Source: World Bank, General Authority of Statistics 04 Doing business guide | Understanding Saudi Arabia’s tax position 05 Doing business guide | Understanding Saudi Arabia’s tax position Market overview • Saudi Arabia is an oil-based economy Government with the largest proven crude oil reserves Government type Monarchy in the world. -

Saudi Arabia 2017 Human Rights Report

SAUDI ARABIA 2017 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is a monarchy ruled by King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, who is both head of state and head of government. The government bases its legitimacy on its interpretation of sharia (Islamic law) and the 1992 Basic Law, which specifies that the rulers of the country shall be male descendants of the founder, King Abdulaziz bin Abdulrahman Al Saud. The Basic Law sets out the system of governance, rights of citizens, powers and duties of the government, and provides that the Quran and Sunna (the traditions of the Prophet Muhammad) serve as the country’s constitution. In 2015 the country held municipal elections on a nonparty basis for two-thirds of the 3,159 seats in the 284 municipal councils around the country. Information on whether the elections met international standards was not available, but independent polling station observers identified no significant irregularities with the elections. For the first time, women were allowed to vote and run as candidates. Civilian authorities generally maintained effective control over the security forces. The most significant human rights issues included unlawful killings, including execution for other than the most serious offenses and without requisite due process; torture; arbitrary arrest and detention, including of lawyers, human rights activists, and antigovernment reformists; political prisoners; arbitrary interference with privacy; restrictions on freedom of expression, including on the internet, and criminalization of libel; restrictions on freedoms of peaceful assembly, association, movement, and religion; citizens’ lack of ability and legal means to choose their government through free and fair elections; trafficking in persons; violence and official gender discrimination against women, although new women’s rights initiatives were announced; and criminalization of same sex sexual activity. -

Saudization As a Solution for Unemployment the Case Of

Saudization as a Solution for Unemployment The Case of Jeddah Western Region Manal Soliman Fakeeh Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate in Business Administration University of Glasgow Business School Faculty of Law Business and Social Science May 2009 II Dedication To my mother, Khadijah J. Attar My first teacher With love III Abstract Saudi Arabia is a young wealthy nation with multiple social and economic problems. While the country is extremely wealthy, it has a young population, many of whom are unemployed. The country is highly dependent on a single resource (oil), and relies heavily on imported labour to meet the requirements of economic growth and contribute to the development of the country. In recognition of these systemic problems, the Government has developed a policy of ‘Saudization’ as a way of replacing expatriate with Saudi workers as a way of solving the problem of unemployment. This thesis is an attempt to understand the roots of this paradox of high wealth and high unemployment. How did Saudi Arabia arrive at a situation where it became dependent on the labour of expatriates and why did the government not use the countries’ wealth to create a vibrant high-skill economy? What strategies is the government using to deal with alarming rates of high unemployment, and how successful are their endeavours. Is Saudization the answer to the current labour market situation and, if not, what are the shortcomings of the policy? These are questions addressed in this thesis. With Saudi Arabia having developed relatively recently, the thesis begins by providing an historical overview of the establishment of the Kingdom and at the impact of the 1970s oil boom. -

Understanding Saudi Private Sector Employment and Unemployment Farah Hani, Michael Lopesciolo

Understanding Saudi Private Sector Employment And Unemployment Farah Hani, Michael Lopesciolo CID Research Fellow and Graduate Student Working Paper Series No. 131 March 2021 (original draft March 2019) © Copyright 2021 of Hani, Farah; Lopesciolo, Michael; and the President and Fellows of Harvard College Understanding Saudi Private Sector Employment And Unemployment Farah Hani1, Michael Lopesciolo2 Working Paper, March 2021 Abstract: This paper analyzes the changes in Saudi employment and unemployment between 2009 and 2018 and argues that a supply-demand skill mismatch exacerbated by insufficient job creation, and prevalent Saudi preferences and beliefs about employment underpin the high unemployment problem that coexists with low Saudi employment in the private sector in the country. Keywords: Saudi Arabia, Employment, Unemployment, Occupations, Jobs JEL Codes: J21, J23, J24 This paper was originally written in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Public Administration in International Development, at John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University. The work was made possible by the Growth Lab’s “Industry Diversification and Job Growth in Saudi Arabia” initiative, which provided access to Saudi labor market data extending between the years 2009-2016. The opinions expressed in this paper do not reflect those of Harvard University, The Growth Lab or the Government of Saudi Arabia. The usual disclaimers apply. We thank Ricardo Hausmann, Anders Jensen, Michael Walton and colleagues at the Growth Lab for their valuable comments on this work. 1 Research Fellow at Harvard’s Center for International Development – the Growth Lab; MPA/ID 2019 2 MPA/ID 2019 2 Executive Summary Why does unemployment persist in Saudi Arabia, a country with labor shortages that had compelled the private sector to recruit workers from abroad? Unemployment is a top policy priority for Saudi Arabia. -

Saudization Framework and Unemployment in Saudi Arabia: Antecedents and Consequences

European Journal of Business and Management www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1905 (Paper) ISSN 2222-2839 (Online) Vol.6, No.17, 2014 Saudization Framework and Unemployment in Saudi Arabia: Antecedents and Consequences Mahmoud Kamal Abouraia Business Administration Department, Ibn Rushd College for Management Sciences, PO Box 447, Abha 61411 Saudi Arabia * E-mail of the corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract It is safe to say that it is not odd to become aware of the unemployment issue from the biggest oil exporter on the planet? The issue of unemployment in Saudi Arabia started to show up at the start of the most recent century. In 1975, Saudization framework was propelled as a method for supplanting exile with Saudi laborers for limitation employments, yet following 37 years of unemployment is still one of the vital subjects of concern to national. In view of this, this paper attempts to discuss the principal reason behind this issue. Also, the paper argues the unemployment aspects that are crucial in Saudi Arabia are training framework, work framework, organizations and outside laborers. In a universe of developing interest for vitality and sailing oil costs, the Saudis have nothing to stress over; Saudi Arabia’s oil stores represent more than 25% of the world’s aggregate and its regular gas stores are hence on the planet after Russia, Iran and Qatar. Then again, the Kingdom confronts some incredible investment challenges which call for consideration in order to achieve their significant objectives. Keywords: Saudization, Saudi Arabia, unemployment 1. Introduction Saudi Arabia is the biggest nation in the Middle East. -

A Targeted Industry Approach for Raising Quality Private-Sector Employment in Saudi Arabia for More Information on This Publication, Visit

C O R P O R A T I O N SHANTHI NATARAJ, HOWARD J. SHATZ, LOUAY CONSTANT, MATTHEW SARGENT, SEAN MCKENNA, YOUSUF ABDELFATAH, FLORENTINE ELOUNDOU NEKOUL, NATHAN VEST, THE DECISION SUPPORT CENTER A Targeted Industry Approach for Raising Quality Private-Sector Employment in Saudi Arabia For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RRA536-1. About RAND The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. To learn more about RAND, visit www.rand.org. Research Integrity Our mission to help improve policy and decisionmaking through research and analysis is enabled through our core values of quality and objectivity and our unwavering commitment to the highest level of integrity and ethical behavior. To help ensure our research and analysis are rigorous, objective, and nonpartisan, we subject our research publications to a robust and exacting quality-assurance process; avoid both the appearance and reality of financial and other conflicts of interest through staff training, project screening, and a policy of mandatory disclosure; and pursue transparency in our research engagements through our commitment to the open publication of our research findings and recommendations, disclosure of the source of funding of published research, and policies to ensure intellectual independence. For more information, visit www.rand.org/about/principles. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif.