Permit to Work Procedure and Certificates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tag out a Shipyard Hazard Prevention Course

Workshop Objectives At the completion of this workshop it is expected that all trainees will pass a quiz, have the ability to identify energy hazards and follow both OSHA and NAVSEA safety procedures associated with: Electrical Hazards Non-Electrical Energy Hazards Lockout - Tag out 11 OSHA 1915.89 SUBPART F Control of Hazardous Energy -Lock-out/ Tags Plus This CFR allows specific exemptions for shipboard tag-outs when Navy Ship’s Force personnel serve as the lockout/tags-plus coordinator and maintain control of the machinery per the Navy’s Tag Out User Manual (TUM). Note to paragraph (c)(4) of this section: When the Navy ship's force maintains control of the machinery, equipment, or systems on a vessel and has implemented such additional measures it determines are necessary, the provisions of paragraph (c)(4)(ii) of this section shall not apply, provided that the employer complies with the verification procedures in paragraph (g) of this section. Note to paragraph (c)(7) of this section: When the Navy ship's force serves as the lockout/tags-plus coordinator and maintains control of the lockout/tags-plus log, the employer will be in compliance with the requirements in paragraph (c)(7) of this section when coordination between the ship's force and the employer occurs to ensure that applicable lockout/tags-plus procedures are followed and documented. 2 Note to paragraph (e) of this section: When the Navy ship's force shuts down any machinery, equipment, or system, and relieves, disconnects, restrains, or otherwise renders safe all potentially hazardous energy that is connected to the machinery, equipment, or system, the employer will be in compliance with the requirements in paragraph (e) of this section when the employer's authorized employee verifies that the machinery, equipment, or system being serviced has been properly shut down, isolated, and deenergized. -

1. Identification

SAFETY DATA SHEET Issuing Date: 13-Aug-2020 Revision date 13-Aug-2020 Revision Number 1 1. IDENTIFICATION Product Name Tide PODS Spring Meadow Product Identifier 91943772_RET_NG Product Type: Finished Product - Retail Recommended use Detergent. Restrictions on use Use only as directed on label. Synonyms C-91943772-005 Details of the supplier of the safety PROCTER & GAMBLE - Fabric and Home Care Division data sheet Ivorydale Technical Centre 5289 Spring Grove Avenue Cincinnati, Ohio 45217-1087 USA Procter & Gamble Inc. P.O. Box 355, Station A Toronto, ON M5W 1C5 1-800-331-3774 E-mail Address [email protected] Emergency Telephone Transportation (24 HR) CHEMTREC - 1-800-424-9300 (U.S./ Canada) or 1-703-527-3887 Mexico toll free in country: 800-681-9531 2. HAZARD IDENTIFICATION "Consumer Products", as defined by the US Consumer Product Safety Act and which are used as intended (typical consumer duration and frequency), are exempt from the OSHA Hazard Communication Standard (29 CFR 1910.1200). This SDS is being provided as a courtesy to help assist in the safe handling and proper use of the product. This product is classified under 29CFR 1910.1200(d) and the Canadian Hazardous Products Regulation as follows:. Hazard Category Acute toxicity - Oral Category 4 Eye Damage / Irritation Category 2B Signal word Warning Hazard statements Harmful if swallowed Causes eye irritation Hazard pictograms 91943772_RET_NG - Tide PODS Spring Meadow Revision date 13-Aug-2020 Precautionary Statements Keep container tightly closed Keep away from heat/sparks/open flames/hot surfaces. — No smoking Wash hands thoroughly after handling Precautionary Statements - In case of fire: Use water, CO2, dry chemical, or foam for extinction Response IF IN EYES: Rinse cautiously with water for several minutes. -

Acute Incidents During Anaesthesia a Small Percentage of Apparently Routine Anaesthetics Will End in an Anticipated Or Unforeseen Acute Incident

Acute incidents during anaesthesia A small percentage of apparently routine anaesthetics will end in an anticipated or unforeseen acute incident. Edwin W Turton, MB ChB, Dip Pec (SA), DA (SA), MMed Anes, FCA (SA) Head of Cardiothoracic Anaesthesia, Bloemfontein Hospitals Complex, Department of Anaesthesiology, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein Dr Edwin Turton worked as a clinical fellow in cardiac anaesthesia at Glenfield Hospital, Leicester, UK, in 2009. His current fields of interest are adult and paediatric cardiac anaesthesia and peri-operative echocardiography, and focussed assessment through echocardiography in emergency care. Correspondence to: E W Turton ([email protected]) Anaesthesia is uneventful in the majority Although anaesthesia is a very well- • Antibiotics (2.6%) of cases but in a small percentage of controlled and governed discipline, acute • Benzodiazepines (2%) routine and emergency cases there will incidents do occur. Incidents can occur • Opioids (1.7%) be an anticipated or an unforeseen acute during induction, maintenance and • Other agents (e.g. radio contrast media) incident. These incidents need immediate emergence from anaesthesia. (2.5%). theoretical knowledge and clinical skills to be managed effectively and to The following acute critical incidents are Treatment and management prevent further morbidity and mortality. discussed in this article: • Stop administration of all suspected Therefore all providers of anaesthesia, • Anaphylaxis agents. at different levels of experience, should • Aspiration • Call for help. be able to provide basic and advanced • Laryngospasm • Airway must be secured and 100% cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).1 • High or total (complete) spinal blocks in oxygen given, and ensure adequate obstetric anaesthesia. ventilation. The first death associated with an anaesthetic • Intravenous or intramuscular adrenaline was reported in 1848 in the USA. -

Personal Protective Equipment Hazard Assessment

WORKER HEALTH AND SAFETY Personal Protective Equipment Hazard Assessment Oregon OSHA Personal Protective Equipment Hazard Assessment About this guide “Personal Protective Equipment Hazard Assessment” is an Oregon OSHA Standards and Technical Resources Section publication. Piracy notice Reprinting, excerpting, or plagiarizing this publication is fine with us as long as it’s not for profit! Please inform Oregon OSHA of your intention as a courtesy. Table of contents What is a PPE hazard assessment ............................................... 2 Why should you do a PPE hazard assessment? .................................. 2 What are Oregon OSHA’s requirements for PPE hazard assessments? ........... 3 Oregon OSHA’s hazard assessment rules ....................................... 3 When is PPE necessary? ........................................................ 4 What types of PPE may be necessary? .......................................... 5 Table 1: Types of PPE ........................................................... 5 How to do a PPE hazard assessment ............................................ 8 Do a baseline survey to identify workplace hazards. 8 Evaluate your employees’ exposures to each hazard identified in the baseline survey ...............................................9 Document your hazard assessment ...................................................10 Do regular workplace inspections ....................................................11 What is a PPE hazard assessment A personal protective equipment (PPE) hazard assessment -

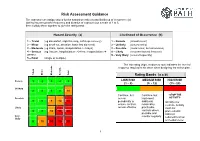

Risk Assessment Guidance

Risk Assessment Guidance The assessor can assign values for the hazard severity (a) and likelihood of occurrence (b) (taking into account the frequency and duration of exposure) on a scale of 1 to 5, then multiply them together to give the rating band: Hazard Severity (a) Likelihood of Occurrence (b) 1 – Trivial (eg discomfort, slight bruising, self-help recovery) 1 – Remote (almost never) 2 – Minor (eg small cut, abrasion, basic first aid need) 2 – Unlikely (occurs rarely) 3 – Moderate (eg strain, sprain, incapacitation > 3 days) 3 – Possible (could occur, but uncommon) 4 – Serious (eg fracture, hospitalisation >24 hrs, incapacitation >4 4 – Likely (recurrent but not frequent) weeks) 5 – Very likely (occurs frequently) 5 – Fatal (single or multiple) The risk rating (high, medium or low) indicates the level of response required to be taken when designing the action plan. Trivial Minor Moderate Serious Fatal Rating Bands (a x b) Remote 1 2 3 4 5 LOW RISK MEDIUM RISK HIGH RISK (1 – 8) (9 - 12) (15 - 25) Unlikely 2 4 6 8 10 Continue, but Continue, but -STOP THE Possible review implement ACTIVITY- 3 6 9 12 15 periodically to additional Identify new ensure controls reasonably controls. Activity Likely remain effective practicable must not controls where 4 8 12 16 20 proceed until possible and risks are Very monitor regularly reduced to a low likely 5 10 15 20 25 or medium level 1 Risk Assessments There are a number of explanations needed in order to understand the process and the form used in this example: HAZARD: Anything that has the potential to cause harm. -

Emergency Procedure Guidelines for Employees, Students and Visitors

Emergency Procedure Guidelines for Employees, Students and Visitors Developed by Environmental Health and Safety Emergency Management GUIDE TO EMERGENCIES ON CAMPUS The information contained in this booklet is being disseminated to assist Slippery Rock University employees, students, residents and visitors in reacting safely to any number of emergency situations which they may face while on campus. This is not an emergency response plan for first responders. It is recommended a printed copy of this booklet be maintained in a visible and accessible area by employees and students including but not limited to office receiving areas and classrooms, lunch and break rooms, information desks in residence halls and student rooms. The SRU Police are available on a 24-hour/7 day-a-week basis to respond to emergencies that may occur on the Slippery Rock University campus. SRU EMERGENCIES AND THREATS OF VIOLENCE CALL 724.738.3333 2 Table of Contents A. Prevention and preparation ............................................................... 4 B. How to report an emergency ............................................................. 5 C. Emergency notification systems ....................................................... 5 D. National Incident Management System .......................................... 6 E. Public information officer.................................................................. 6 F. Emergency operations center ............................................................ 6 G. Emergency response and action plans ............................................. -

Permits-To-Work in the Process Industries

SYMPOSIUM SERIES NO. 151 # 2006 IChemE PERMITS-TO-WORK IN THE PROCESS INDUSTRIES John Gould Environmental Resources Management, Suite 8.01, 8 Exchange Quay, Manchester M5 3EJ; [email protected] The paper presents the collective results from a number of Safety Management System audits. The audit protocol is based on the Health and Safety Executive pub- lication ‘Successful health and safety management’ and takes into account formal (written) and informal procedures as well as their implementation. Focused on permit-to-work systems, these have shown a number of common failings. The most common failure in implementing a permit-to-work system is the issue of too many permits. However, the audit protocol considers the whole risk control system. The failure to ‘close’ the management loop with an effective regular review process is the largest obstacle to an effective permit system. INTRODUCTION ‘Permits save lives – give them proper attention’. This is a startling statement made by the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) in its free leaflet IND(G) 98 (Rev 3) PTW systems. The leaflet goes on to state that two thirds of all accidents in the chemical industry are main- tenance related, with the permit-to-work (PTW) failures being the largest single cause. Given these facts, it comes as no surprise that PTW systems are a key part in the provision of a safe working environment. Over the past four years Environmental Resources Management (ERM) has been auditing PTW systems as part of its key risk control systems audits. Numerous systems have been evaluated from a wide rage of industries, covering personal care products man- ufacturing to refinery operations. -

Emergency Evacuation Plan

Emergency Evacuation Plan Introduction: It is important to plan ahead and to protect your employees during an emergency. For fire related emergencies, always use the emergency exit closest to you and have an alternate route in case an exit is blocked. If possible shut-off any equipment you are operating before leaving your work area. If there is a possible gas leak, evacuate the area immediately. Do not use the phone , this includes landlines and mobile phones, do not turn on or off lights, and do not use any electrical device. For weather related emergencies, plan a head so you know the plan to carry out. Discussion Points: • Plan ahead, know the nearest emergency exits from your work area, and designate a meeting place. • Plan, train, communicate and conduct practice drills. • Maintain a clear passage for your escape route, do not block or lock exits. • Identify storm-shelters within the facility in the case of a tornado, earthquake or flash flooding. • Remain calm and follow proper safety procedures. Discussion: During a tornado warning, take shelter in a basement or in a small room within the center of the building away from windows. Flash flooding is a common weather hazard that occurs frequently in a short period of time. If you are driving and approach a water-covered roadway, turn around and do not go around barricades, it is against the law! Also you often hear the message on the radio or television; Turn around! Don’t drown! It only takes six inches of water to wash away your vehicle. In all instances remain calm and follow proper safety procedures. -

PPE, Part 8 Sections 111 to 117, Part 9 Sections 118 to 122 of the Occupational Health and Safety Regulations

NORTHWEST TERRITORIES & NUNAVUT CODES OF PRACTICE In accordance with the Northwest Territories and Nunavut Safety Acts and Occupational Health and Safety Regulations PERSONAL PROTECTIVE EQUIPMENT BASICS Code of Practice PERSONAL PROTECTIVE EQUIPMENT BASICS NORTHWEST TERRITORIES WHAT IS A CODE OF PRACTICE? wscc.nt.ca The Workers’ Safety and Compensation Commission (WSCC) Yellowknife Box 8888, 5022 49th Street Codes of Practice (COP) provide practical guidance to achieve the Centre Square Tower, 5th Floor safety requirements of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut Yellowknife, NT X1A 2R3 Safety Acts and related Regulations. Telephone: 867-920-3888 Codes of Practice come into effect in each territory on the day Toll Free: 1-800-661-0792 they are published in the Northwest Territories Gazette and Fax: 867-873-4596 Nunavut Gazette. Toll Free Fax: 1-866-277-3677 Codes of Practice do not have the same legal force as the Acts, Inuvik Mining Regulations, Occupational Health and Safety Box 1188, 85 Kingmingya Road the or the Regulations. A person or employer cannot face prosecution for Blackstone Building, Unit 87 Inuvik, NT X0E 0T0 failing to comply with a COP. They are considered industry best practice and may be a consideration when determining whether Telephone: 867-678-2301 Safety Acts Fax: 867 -678-2302 an employer or worker has complied with the and Regulations in legal proceedings. NUNAVUT As per subsection 18(3) of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut wscc.nu.ca Safety Acts, “For the purpose of providing practical guidance with respect -

Operational Risk Management Guide

OPERATIONAL RISK MANAGEMENT GUIDE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE FOREST SERVICE 2020 Last Updated 02/26/2020 RISK MANAGEMENT COUNCIL IN COOPERATION WITH THE OFFICE OF SAFETY & OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH and THE NATIONAL AVIATION SAFETY COUNCIL Contents Contents ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................................................. i Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................... 1 What is Operational Risk Management? ................................................................................................................... 1 The Terminology of ORM ................................................................................................................................................ 1 Principles of ORM Application ........................................................................................................................................... 6 The Five-Step ORM Process ................................................................................................................................................ 7 Step 1: Identify Hazards .................................................................................................................................................. -

Report on Occupational Safety and Health Inspections

Occupational Safety and Health Standards Covering Hazards Observed During Inspection of Legislative Branch Facilities The following is a brief description of the major safety and health standards referenced in this Report. The standards are published in Title 29 of the Code of Federal Regulations (“CFR”) and are summarized below. The CFR should be consulted for a complete explanation of the specific standards listed. Statutory Requirement 29 U.S.C. 641(a)(1) General Duty Clause – The OSH Act requires that every employer provide its employees with a safe and hazard-free workplace. The workplace must be “free from recognized hazards that are causing or are likely to cause death or serious physical harm” to the employees. OSH Standard (29 CFR Section) Brief description/subject EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS, FIRE AND OTHER EMERGENCIES 1910.36 Safe Means of Egress from Fire and Other Emergencies – Every building, new or old, shall have sufficient exits to permit the prompt escape of occupants in case of fire or other emergency. – Emergency exits must be clearly visible and the routes to the exits conspicuously marked. – There must be at least two exits, remote from each other, located in such a way to minimize the possibility that both will be blocked by fire or other emergency. 1910.37 Exit Routes and Signs – Exits and the way of approach to, and travel from, exits shall be maintained so that they are unobstructed and are accessible at all times. – Exit doors serving more than 50 people, or in high-hazard areas, must swing in the direction of exit travel. – Exit doors and fire barriers must be maintained and in serviceable condition at all times. -

Code of Practice for Warehouse and Terminal Facilities Storing Hazardous Materials

Special Hazard Situations 169 ACKNOWLEDGMENT tion Service, 5285 Port Royal Rd., Springfield, Va. 22161). The authors would like to express their appreciation 3. Tanker Casualties Report. Imco No. 78.16E, Lon for the assistance provided by Steve Bailey of ICF, don, England, 1978. Incorporated, and Betty Alix, Dan Bower, Jo Ann 4. J .D. Porricelli and V.F. Keith. Tankers and the Grega, and Diana Rogers of Rensselaer Polytechnic U.S. Energy Situation: An Economic and Environ Institute. mental Analysis. In Marine Technology, Oct. 1974, pp. 340-364. ~ 5. N. Meade, T. LaPointe, and R. Anderson. Multi variate Analysis of Worldwide Tanker Casualties. REFERENCES Proc., Oil Spill 8th Conference, San Antonio, Tex., 1983, pp. 553-557. 1. J.J. Henry Company, Inc. An Analysis of Oil Out 6. M.A. Froelich and J.F. Bellantoni. Oil Spill flows Due to Tanker Accidents, 1971-72. Report Rates in Four U.S. Coastal Regions. Proc., 1981 AD-780315. U.S. Coast Guard, U.S. Department of Oil Spill Conference, American Petroleum Insti Transportation, Washington, o.c., Nov. 1973. tute, Washington, D.C., 1981, pp. 677-683. 2. Offshore Petroleum Transfer Systems for Washing 7. Polluting Incidents in and Around u. S. Waters, ton State: A Feasibility Study, Oceanographic Calendar Year 1981 and 1982. U.S. Coast Guard, Institute of Washington, Seattle, Dec. 19741 U .s. Department of Transportation, Washington, NTIS PB-244 945/2 (National Technical Informa- D.C., Dec. 1983. Code of Practice for Warehouse and Terminal Facilities Storing Hazardous Materials James F. LaMorte and Donald L. Williams ABSTRACT Practical standards are needed to guide the construction and operation of Canadian warehouses and transport terminals in which packaged hazardous mate rials are stored.