EPISODE 4: Sing Like an American

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compact Discs by 20Th Century Composers Recent Releases - Spring 2020

Compact Discs by 20th Century Composers Recent Releases - Spring 2020 Compact Discs Adams, John Luther, 1953- Become Desert. 1 CDs 1 DVDs $19.98 Brooklyn, NY: Cantaloupe ©2019 CA 21148 2 713746314828 Ludovic Morlot conducts the Seattle Symphony. Includes one CD, and one video disc with a 5.1 surround sound mix. http://www.tfront.com/p-476866-become-desert.aspx Canticles of The Holy Wind. $16.98 Brooklyn, NY: Cantaloupe ©2017 CA 21131 2 713746313128 http://www.tfront.com/p-472325-canticles-of-the-holy-wind.aspx Adams, John, 1947- John Adams Album / Kent Nagano. $13.98 New York: Decca Records ©2019 DCA B003108502 2 028948349388 Contents: Common Tones in Simple Time -- 1. First Movement -- 2. the Anfortas Wound -- 3. Meister Eckhardt and Quackie -- Short Ride in a Fast Machine. Nagano conducts the Orchestre Symphonique de Montreal. http://www.tfront.com/p-482024-john-adams-album-kent-nagano.aspx Ades, Thomas, 1971- Colette [Original Motion Picture Soundtrack]. $14.98 Lake Shore Records ©2019 LKSO 35352 2 780163535228 Music from the film starring Keira Knightley. http://www.tfront.com/p-476302-colette-[original-motion-picture-soundtrack].aspx Agnew, Roy, 1891-1944. Piano Music / Stephanie McCallum, Piano. $18.98 London: Toccata Classics ©2019 TOCC 0496 5060113444967 Piano music by the early 20th century Australian composer. http://www.tfront.com/p-481657-piano-music-stephanie-mccallum-piano.aspx Aharonian, Coriun, 1940-2017. Carta. $18.98 Wien: Wergo Records ©2019 WER 7374 2 4010228737424 The music of the late Uruguayan composer is performed by Ensemble Aventure and SWF-Sinfonieorchester Baden-Baden. http://www.tfront.com/p-483640-carta.aspx Ahmas, Harri, 1957- Organ Music / Jan Lehtola, Organ. -

2021 Contemporary Women Composers Music Catalog

Catalog of Recent Highlights of Works by Women Composers Spring 2021 Agócs, Kati, 1975- Debrecen Passion : For Twelve Female Voices and Chamber Orchestra (2015). ©2015,[2020] Spiral; Full Score; 43 cm.; 94 p. $59.50 Needham, MA: Kati Agócs Music Immutable Dreams : For Pierrot Ensemble (2007). ©2007,[2020] Spiral; Score & 5 Parts; 33 $59.50 Needham, MA: Kati Agócs Music Rogue Emoji : For Flute, Clarinet, Violin and Cello (2019). ©2019 Score & 4 Parts; 31 cm.; 42, $49.50 Needham, MA: Kati Agócs Music Saint Elizabeth Bells : For Violoncello and Cimbalom (2012). ©2012,[2020] Score; 31 cm.; 8 p. $34.50 Needham, MA: Kati Agócs Music Thirst and Quenching : For Solo Violin (2020). ©2020 Score; 31 cm.; 4 p. $12.50 Needham, MA: Kati Agócs Music Albert, Adrienne, 1941- Serenade : For Solo Bassoon. ©2020 Score; 28 cm.; 4 p. $15.00 Los Angeles: Kenter Canyon Music Tango Alono : For Solo Oboe. ©2020 Score; 28 cm.; 4 p. $15.00 Los Angeles: Kenter Canyon Music Amelkina-Vera, Olga, 1976- Cloches (Polyphonic Etude) : For Solo Guitar. ©2020 Score; 30 cm.; 3 p. $5.00 Saint-Romuald: Productions D'oz DZ3480 9782897953973 Ensueño Y Danza : For Guitar. ©2020 Score; 30 cm.; 8 p. $8.00 Saint-Romuald: Productions D'oz DZ3588 9782897955052 Andrews, Stephanie K., 1968- On Compassion : For SATB Soli, SATB Chorus (Divisi) and Piano (2014) ©2017 Score - Download; 26 cm.; 12 $2.35 Boston: Galaxy Music 1.3417 Arismendi, Diana, 1962- Aguas Lustrales : For String Quartet (1992). ©2019 Score & 4 Parts; 31 cm.; 15, $40.00 Minot, Nd: Latin American Frontiers International Pub. -

Network Notebook

Network Notebook Summer Quarter 2019 (July - September) A World of Services for Our Affiliates We make great radio as affordable as possible: • Our production costs are primarily covered by our arts partners and outside funding, not from our affiliates, marketing or sales. • Affiliation fees only apply when a station takes three or more programs. The actual affiliation fee is based on a station’s market share. Affiliates are not charged fees for the selection of WFMT Radio Network programs on the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). • The cost of our Beethoven and Jazz Network overnight services is based on a sliding scale, depending on the number of hours you use (the more hours you use, the lower the hourly rate). We also offer reduced Beethoven and Jazz Network rates for HD broadcast. Through PRX, you can schedule any hour of the Beethoven or Jazz Network throughout the day and the files are delivered a week in advance for maximum flexibility. We provide highly skilled technical support: • Programs are available through the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). PRX delivers files to you days in advance so you can schedule them for broadcast at your convenience. We provide technical support in conjunction with PRX to answer all your distribution questions. In cases of emergency or for use as an alternate distribution platform, we also offer an FTP (File Transfer Protocol), which is kept up to date with all of our series and specials. We keep you informed about our shows and help you promote them to your listeners: • Affiliates receive our quarterly Network Notebook with all our program offerings, and our regular online WFMT Radio Network Newsletter, with news updates, previews of upcoming shows and more. -

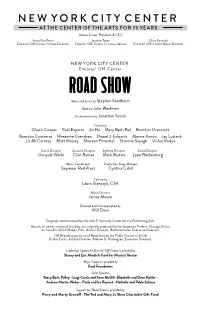

Read the Road Show Program

NEW YORK CITY CENTER AT THE CENTER OF THE ARTS FOR 75 YEARS Arlene Shuler, President & CEO Anne Kauffman Jeanine Tesori Chris Fenwick Encores! Off-Center Artistic Director Encores! Off-Center Creative Advisor Encores! Off-Center Music Director NEW YORK CITY CENTER Encores! Off-Center Music and Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim Book by John Weidman Orchestrations by Jonathan Tunick Featuring Chuck Cooper Raúl Esparza Jin Ha Mary Beth Peil Brandon Uranowitz Brandon Contreras Rheaume Crenshaw Daniel J. Edwards Marina Kondo Jay Lusteck Liz McCartney Matt Moisey Shereen Pimentel Sharone Sayegh Vishal Vaidya Scenic Designer Costume Designer Lighting Designer Sound Designer Donyale Werle Clint Ramos Mark Barton Leon Rothenberg Music Coordinator Production Stage Manager Seymour Red Press Cynthia Cahill Casting by Laura Stanczyk, CSA Music Director James Moore Directed and Choreographed by Will Davis Originally commissioned by the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. Bounce, an earlier version of this play, was originally produced by the Goodman Theatre, Chicago, Illinois on June 30, 2003 (Robert Falls, Artistic Director; Roche Schulfer, Executive Director). Off-Broadway premiere of Road Show by the Public Theater in 2008 (Oskar Eustis, Artistic Director; Andrew D. Hamingson, Executive Director). Leadership Support for Encores! Off-Center is provided by Stacey and Eric Mindich Fund for Musical Theater Major Support is provided by Ford Foundation Series Sponsors Stacy Bash-Polley • Luigi Caiola and Sean McGill • Elizabeth and Dean Kehler • -

Wwciguide November 2019.Pdf

From the President & CEO The Guide The Member Magazine for WTTW and WFMT Dear Member, Renée Crown Public Media Center This month, WTTW will bring you a film about the transformative power of 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60625 education. College Behind Bars follows twelve incarcerated men and women who hope to turn their lives around by earning a college degree, as we follow their Main Switchboard four-year journey through the famously rigorous Bard Prison Initiative. Join us (773) 583-5000 on two consecutive nights for a compelling documentary on America’s criminal Member and Viewer Services (773) 509-1111 x 6 justice system. Also on WTTW, The Chaperone reunites three talents from Downton Abbey – Websites actor Elizabeth McGovern, series creator Julian Fellowes, and director Michael wttw.com wfmt.com Engler – for this 1920s era story of a Kansas woman who accompanies an aspiring teen dancer on a tumultuous trip to New York City. A new series on WTTW Kids, Publisher Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum, introduces children aged 4-7 to historical Anne Gleason figures. On wttw.com, learn more about the small-town fraud that went on in Art Director Tom Peth Dixon, Illinois in our interview with the filmmaker of the documentary,All the WTTW Contributors Queen’s Horses. Julia Maish Lisa Tipton WFMT will present a live performance from New York’s Carnegie Hall by WFMT Contributors Riccardo Muti and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. And in observance of Andrea Lamoreaux Veterans Day, Chicago Tribune film critic Michael Phillips will present his sampling of music from war-themed movies old and new. -

NYPHIL+ AVAILABLE CONTENT LISTING (As of July 12, 2021; Updates Appear in Bold)

NYPHIL+ AVAILABLE CONTENT LISTING (As of July 12, 2021; Updates appear in bold) RECENT ORCHESTRAL PERFORMANCES JAAP VAN ZWEDEN CONDUCTS: WALKER, MOZART, AND SHOSTAKOVICH WITH YEFIM BRONFMAN AND CHRISTOPHER MARTIN Jaap van Zweden, conductor Yefim Bronfman, piano Christopher Martin, trumpet WALKER Lyric for Strings SHOSTAKOVICH Concerto No. 1 in C minor for Piano, Trumpet, and Strings MOZART Serenade No. 10 in B-flat major, Gran partita YOUNG PEOPLE’S CONCERT: HOPE AND HEALING Episode 1: The Art of Listening Thomas Wilkins, conductor / host Doug Fitch, art designer (Vivaldi) Tommy Nguyen, art designer (Vivaldi) Jaymie Rehberger, dancer (Bartók) Deanna Day Cruz, dancer (Bartók) Ali-asha Polson, dancer (Bartók) Habib Azar, creative consultant Frank Sinatra School of the Arts High School, partner VIVALDI / Arr. J. SORRELL Trio Sonata in D minor, La folia Ilana RAHIM-BRADEN I Am Composition, but Stronger (World Premiere) BARTÓK Selections from Romanian Folk Dances Episode 2: Where We Find Hope Thomas Wilkins, conductor / host Tito Muñoz, conductor (Still) Laquita Mitchell, soprano (Price) Aaron Diehl, piano (Still) Sean Clements, bomba musician Serena Yang, NYC Youth Poet Laureate Dr. Camea Davis, National Youth Poet Laureate Network Director, Urban Word NYC Habib Azar, creative consultant Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts, partner (Still) PRICE Hold Fast to Dreams Roberto SIERRA Rápido, from Sinfonietta (New York Premiere) STILL Out of the Silence, from Seven Traceries Jessie MONTGOMERY Starburst Episode 3: Mind, Body, Spirit, Music Thomas Wilkins, conductor / host Tito Muñoz, conductor (M.L. Williams) Aaron Diehl, piano (M.L. Williams) Jaymie Rehberger, dancer (J.S. Bach) Deanna Day Cruz, dancer (J.S. -

(More) for IMMEDIATE RELEASE August 16, 2019 Decca Gold

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE August 16, 2019 Decca Gold Contact: New York Philharmonic Contact: Julia Casey (212) 331-2078 Deirdre Roddin (212) 875-5700 [email protected] [email protected] Ashley Natareno (212) 331-2232 [email protected] JULIA WOLFE’s Fire in my mouth World Premiere Performances by NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC and MUSIC DIRECTOR JAAP VAN ZWEDEN, The Crossing, and Young People’s Chorus of New York City TO BE RELEASED ON DECCA GOLD Digital Formats: August 30, 2019 Physical Format: October 4, 2019 NOW AVAILABLE FOR PREORDER The New York Philharmonic and Music Director Jaap van Zweden’s World Premiere performances of Julia Wolfe’s Fire in my mouth will be released in digital formats on August 30, 2019, and in physical format on October 4, 2019, on Decca Gold, Universal Music Group’s newly established US classical music label. It is now available for preorder at https://DeccaGold.lnk.to/Fireinmymouth. The release will mark Decca Gold’s fifth New York Philharmonic album. The New York Philharmonic premiered Julia Wolfe’s Fire in my mouth, which the Orchestra also co-commissioned, in January 2019, conducted by Jaap van Zweden and featuring The Crossing, conducted by Donald Nally, and the Young People’s Chorus of New York City, directed by Francisco J. Núñez. The New York Times called the work “ambitious, heartfelt, often compelling. … There is both heady optimism and a sense of dread in Ms. Wolfe’s music. … Mr. van Zweden led a commanding account of a score that … ends with an elegiac final chorus in which the names of all 146 victims are tenderly sung to create a fabric of music and memory.” The performance earned the coveted spot in the highbrow / brilliant quadrant of New York magazine’s Approval Matrix. -

Introducing Music Director Jaap Van Zweden

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE UPDATED September 6, 2018 August 14, 2018 Contact: Deirdre Roddin (212) 875-5700; [email protected] INTRODUCING MUSIC DIRECTOR JAAP VAN ZWEDEN Inaugural Opening Gala Concert: New York, Meet Jaap September 20 WORLD PREMIERE–PHILHARMONIC COMMISSION of ASHLEY FURE’s Filament STRAVINSKY’s The Rite of Spring RAVEL’s Piano Concerto in G major with DANIIL TRIFONOV EMPIRE STATE BUILDING To Be Lit Philharmonic Red in Celebration Opening Subscription Program September 21–22 and 25 Ashley FURE’s Filament, STRAVINSKY’s The Rite of Spring, BEETHOVEN’s Emperor Concerto with DANIIL TRIFONOV FREE OPEN REHEARSAL on September 27 A Gift to New York from Jaap van Zweden and the Orchestra NEW PERMANENT EXHIBITS by New York Philharmonic Archives To Honor Jaap van Zweden’s Inaugural Season PHILHARMONIC FREE FRIDAYS Begins Fifth Season on September 21 Jaap van Zweden will begin his tenure as the 26th Music Director of the New York Philharmonic with his inaugural Opening Gala Concert, New York, Meet Jaap, Thursday, September 20, 2018. The program will feature the World Premiere of Ashley Fure’s Filament, commissioned by the Philharmonic for the occasion; Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring; and Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G major with Daniil Trifonov as soloist. Jaap van Zweden will also conduct the 2018–19 season’s first three subscription weeks, starting with the opening subscription program September 21–22 and 25, 2018, reprising Ms. Fure’s Filament and The Rite of Spring; Daniil Trifonov will return as soloist, this time in Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 5, Emperor. -

Strategic Plan Will Guide the Organization’S Path Forward, Setting the Stage for Broader Impact Within the Choral Community

2019-2020 SEASON | Volume I, Issue III FLORIDA’S GRAMMY® NOMINATED VOCAL ENSEMBLE MAGAZINE SERAPHIC FIRE SETS THE STAGE FOR A DECADE OF GROWTH READ MORE - PAGE 26 COMING JUNE 2020 SERAPHIC FIRE HOSTS CHORUS AMERICA LEARN MORE - PAGE 8 ANNOUNCING 2020-2021 SEASON READ MORE - PAGE 16 BOCA RATON | CORAL GABLES | FT. LAUDERDALE | MIAMI | MIAMI BEACH | NAPLES 1 | SEASON EIGHTEEN IT’S A SUITE NEW STAY Springhill Suites Miami Downtown/Medical Center It’s a space all your own at the SpringHill Suites® Miami Downtown/ Medical Center. Our recently completed head-to-toe remodel features an all-new lobby, common spaces and meeting rooms. Unwind in our newly redesigned, over-sized suites featuring new carpet, paint and decor as MISSION well as free WiFi, a mini-refrigerator, microwave and plush bedding with Seraphic Fire presents the highest quality performances of historically significant cotton-rich linens. Enjoy a Complimentary hot breakfast each morning, and later in the day savor casual American fare & cocktails at 13 Eleven. and under-performed music, and advances art through the professional development, And with shuttle service throughout the medical district, Bayside and refinement, and documentation of our musicians’ talents while promoting Port of Miami, you can spend less time driving and more time making community connectivity through educational programs. the most of your stay. BOOK AHEAD AND SAVE UP TO 20% BY USING CODE “ADP”. CONTENTS To book, call 305-575-5300 or Pre-Concert Conversations .............. 4 visit SpringhillSuitesMiami.com Chorus America 2020 .................7-9 Artists ...........................10-15 2020-21 Season ...................16-18 SpringHill Suites Miami Downtown/Medical Center March Program ..................... -

Music Sales Classical Season Highlights 2018–2019 Composers Composers

MUSIC SALES CLASSICAL SEASON HIGHLIGHTS 2018–2019 COMPOSERS COMPOSERS MISSY MAZZOLI MAJA S K RATKJE Maestro Riccardo Muti has named Missy Edition Wilhelm Hansen signed the Norwegian Mazzoli as the new Mead Composer-in-Resi- composer Maja S K Ratkje in spring 2018. dence with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra Ratkje works across a broad spectrum, NICO MUHLY for the next two seasons. The residency from concert music to performance, instal- The opera Marnie by Nico Muhly receives includes performances of her existing work, lation and noise music. Her music has been its Metropolitan Opera premiere October new commissions, curatorial work for their performed worldwide by Ensemble Intercon- 19–November 10, along with a cinecast MusicNOW series, and a role as advocate temporain, Klangforum Wien, BBC Scottish on November 10 with all performances for the orchestra. Her opera Proving Up Symphony Orchestra, Cikada and many more. conducted by Robert Spano. Yannick Nézet- opens the 30th-anniversary season of New Ratkje has received a number of awards Séguin conducts the Philadelphia Orchestra York City’s Miller Theatre September 26-28 including the Arne Nordheim prize in 2001. in the premiere of the Marnie Suite in in James Darrah’s production. The European She is also active as a singer and performer, September, with a further performance premiere of Breaking the Waves is featured with visual art and text material often being at Carnegie Hall. In November Ballett am at the 2019 Edinburgh Festival in a new part of her work. Rhein present choreography by Robert Binet production from Opera Ventures and Scot- with new arrangements of Four Studies and tish Opera, directed by Tom Morris. -

View List (.Pdf)

Symphony Society of New York Stadium Concert New York Philharmonic Commission New York Philharmonic 150th Anniversary Commission World Premieres New York Philharmonic Messages for the Millennium Commission as of November 30, 2020 NY PHIL Biennial NY PHIL Biennial Commission Joint Commission Members of / musicians from the New York Philharmonic Click to jump to decade 1842-99 | 1900-09 | 1910-19 | 1920-29 | 1930-39 | 1940-49 | 1950-59 1960-69 | 1970-79 | 1980-89 | 1990-99 | 2000-09 | 2010-19 | 2020 Composer Work Date Conductor 1842 – 1899 Loder Concert Overture, Marmion 17-Jan 1846 Loder Bristow Concert Overture, Op. 3 9-Jan 1847 Timm Bristow Symphony No. 4, Arcadian 14-Feb 1874 Bergmann Liszt Symphonic Poem No. 2, Tasso: lamento e trionfo 24-Mar 1877 L.Damrosch Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 2 12-Nov 1881 Thomas R. Strauss Symphony in F minor, Op. 12 13-Dec 1884 Thomas Stanford Symphony No. 3 in F minor, Op. 28 (Irish) 28-Jan 1888 W.Damrosch Lalo Arlequin 28-Nov 1892 W.Damrosch Beach Scena and Aria from Mary Stuart 2-Dec 1892 W.Damrosch Dvořák Symphony No. 9, From the New World (formerly No. 5) 16-Dec 1893 Seidl Herbert Cello Concerto No. 2 9-Mar 1894 Seidl Damrosch Scarlet letter, The 04-Jan 1895 W.Damrosch 1900 – 1909 Hadley Symphony No. 2, The Four Seasons 21-Dec 1901 Paur Burmeister Dramatic Tone Poem, The Sisters 10-Jan 1902 Paur Rezniček Donna Dianna 23-Nov 1907 W.Damrosch Lyapunov Concerto for Piano and Orchestra 7-Dec 1907 W.Damrosch Hofmann Concerto for Pianoforte No. -

HENRY and LEIGH BIENEN SCHOOL of MUSIC SPRING 2019 Fanfare

HENRY AND LEIGH BIENEN SCHOOL OF MUSIC SPRING 2019 fanfare 162220.indd 1 3/14/19 6:32 AM first chair A MESSAGE FROM THE DEAN One of my greatest rewards as dean of the Bienen School of cities across the globe. I performed Korean music with the Music is the opportunity to engage with our alumni. Many Northwestern Alumni Music Ensemble, consisting entirely graduates hold positions in orchestras, military bands, educa- of Bienen School alumni, and played the fourth movement tional institutions, and arts organizations across this country of César Franck’s violin-piano sonata with Sue Hyon Kim and around the world. Our alumni provide vivid proof that a (Cert94). The experience of performing with these alumni Bienen School education prepares students for virtually any made the trip especially meaningful to me. career path they may choose to pursue. Here on campus, the Bienen School offers additional During my tenure as dean, the Bienen School has hosted opportunities for alumni to reconnect. In November nearly high-profile alumni events in conjunction with performances 40 music education alumni returned to Evanston for a two- by the San Francisco Symphony, San Francisco Opera, and day conference hosted by the school’s Center for the Study New York Philharmonic—all featuring numerous alumni of Education and the Musical Experience. And on June 9, in performers—as well as by Northwestern ensembles in celebration of the 50th anniversary of our Symphonic Wind Chicago’s Millennium Park and the Northwestern University Ensemble, director of bands Mallory Thompson will conduct Symphony Orchestra on tour last spring in Beijing, Shanghai, a special all-alumni concert honoring the ensemble’s legacy and Hong Kong.