Arxiv:1706.03391V2 [Astro-Ph.CO] 12 Sep 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Electron-Positron Pairs in Physics and Astrophysics

Electron-positron pairs in physics and astrophysics: from heavy nuclei to black holes Remo Ruffini1,2,3, Gregory Vereshchagin1 and She-Sheng Xue1 1 ICRANet and ICRA, p.le della Repubblica 10, 65100 Pescara, Italy, 2 Dip. di Fisica, Universit`adi Roma “La Sapienza”, Piazzale Aldo Moro 5, I-00185 Roma, Italy, 3 ICRANet, Universit´ede Nice Sophia Antipolis, Grand Chˆateau, BP 2135, 28, avenue de Valrose, 06103 NICE CEDEX 2, France. Abstract Due to the interaction of physics and astrophysics we are witnessing in these years a splendid synthesis of theoretical, experimental and observational results originating from three fundamental physical processes. They were originally proposed by Dirac, by Breit and Wheeler and by Sauter, Heisenberg, Euler and Schwinger. For almost seventy years they have all three been followed by a continued effort of experimental verification on Earth-based experiments. The Dirac process, e+e 2γ, has been by − → far the most successful. It has obtained extremely accurate experimental verification and has led as well to an enormous number of new physics in possibly one of the most fruitful experimental avenues by introduction of storage rings in Frascati and followed by the largest accelerators worldwide: DESY, SLAC etc. The Breit–Wheeler process, 2γ e+e , although conceptually simple, being the inverse process of the Dirac one, → − has been by far one of the most difficult to be verified experimentally. Only recently, through the technology based on free electron X-ray laser and its numerous applications in Earth-based experiments, some first indications of its possible verification have been reached. The vacuum polarization process in strong electromagnetic field, pioneered by Sauter, Heisenberg, Euler and Schwinger, introduced the concept of critical electric 2 3 field Ec = mec /(e ). -

1.3.4 Atoms and Molecules Name Symbol Definition SI Unit

1.3.4 Atoms and molecules Name Symbol Definition SI unit Notes nucleon number, A 1 mass number proton number, Z 1 atomic number neutron number N N = A - Z 1 electron rest mass me kg (1) mass of atom, ma, m kg atomic mass 12 atomic mass constant mu mu = ma( C)/12 kg (1), (2) mass excess ∆ ∆ = ma - Amu kg elementary charge, e C proton charage Planck constant h J s Planck constant/2π h h = h/2π J s 2 2 Bohr radius a0 a0 = 4πε0 h /mee m -1 Rydberg constant R∞ R∞ = Eh/2hc m 2 fine structure constant α α = e /4πε0 h c 1 ionization energy Ei J electron affinity Eea J (1) Analogous symbols are used for other particles with subscripts: p for proton, n for neutron, a for atom, N for nucleus, etc. (2) mu is equal to the unified atomic mass unit, with symbol u, i.e. mu = 1 u. In biochemistry the name dalton, with symbol Da, is used for the unified atomic mass unit, although the name and symbols have not been accepted by CGPM. Chapter 1 - 1 Name Symbol Definition SI unit Notes electronegativity χ χ = ½(Ei +Eea) J (3) dissociation energy Ed, D J from the ground state D0 J (4) from the potential De J (4) minimum principal quantum n E = -hcR/n2 1 number (H atom) angular momentum see under Spectroscopy, section 3.5. quantum numbers -1 magnetic dipole m, µ Ep = -m⋅⋅⋅B J T (5) moment of a molecule magnetizability ξ m = ξB J T-2 of a molecule -1 Bohr magneton µB µB = eh/2me J T (3) The concept of electronegativity was intoduced by L. -

Useful Constants

Appendix A Useful Constants A.1 Physical Constants Table A.1 Physical constants in SI units Symbol Constant Value c Speed of light 2.997925 × 108 m/s −19 e Elementary charge 1.602191 × 10 C −12 2 2 3 ε0 Permittivity 8.854 × 10 C s / kgm −7 2 μ0 Permeability 4π × 10 kgm/C −27 mH Atomic mass unit 1.660531 × 10 kg −31 me Electron mass 9.109558 × 10 kg −27 mp Proton mass 1.672614 × 10 kg −27 mn Neutron mass 1.674920 × 10 kg h Planck constant 6.626196 × 10−34 Js h¯ Planck constant 1.054591 × 10−34 Js R Gas constant 8.314510 × 103 J/(kgK) −23 k Boltzmann constant 1.380622 × 10 J/K −8 2 4 σ Stefan–Boltzmann constant 5.66961 × 10 W/ m K G Gravitational constant 6.6732 × 10−11 m3/ kgs2 M. Benacquista, An Introduction to the Evolution of Single and Binary Stars, 223 Undergraduate Lecture Notes in Physics, DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-9991-7, © Springer Science+Business Media New York 2013 224 A Useful Constants Table A.2 Useful combinations and alternate units Symbol Constant Value 2 mHc Atomic mass unit 931.50MeV 2 mec Electron rest mass energy 511.00keV 2 mpc Proton rest mass energy 938.28MeV 2 mnc Neutron rest mass energy 939.57MeV h Planck constant 4.136 × 10−15 eVs h¯ Planck constant 6.582 × 10−16 eVs k Boltzmann constant 8.617 × 10−5 eV/K hc 1,240eVnm hc¯ 197.3eVnm 2 e /(4πε0) 1.440eVnm A.2 Astronomical Constants Table A.3 Astronomical units Symbol Constant Value AU Astronomical unit 1.4959787066 × 1011 m ly Light year 9.460730472 × 1015 m pc Parsec 2.0624806 × 105 AU 3.2615638ly 3.0856776 × 1016 m d Sidereal day 23h 56m 04.0905309s 8.61640905309 -

International Centre for Theoretical Physics

IC/95/253 INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR THEORETICAL PHYSICS LOCALIZED STRUCTURES OF ELECTROMAGNETIC WAVES IN HOT ELECTRON-POSITRON PLASMA S. Kartal L.N. Tsintsadze and V.I. Berezhiani MIRAMARE-TRIESTE y s. - - INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY £ ,. AGENCY .v ^^ ^ UNITED NATIONS T " ; . EDUCATIONAL, i r' * SCI ENTI FIC- * -- AND CULTURAL j * - ORGANIZATION VOL 2 7 Ni 0 6 IC/95/253 International Atomic Energy Agency and United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR THEORETICAL PHYSICS LOCALIZED STRUCTURES OF ELECTROMAGNETIC WAVES IN HOT ELECTRON-POSITRON PLASMA ' S. K'urtaF, L.N. Tsiiitsacfzc'' ancf V./. fiercz/iiani International Centre for Theoretical Physics, Trieste, Italy. ABSTRACT The dynamics of relativistically strong electromagnetic (EM) wave propagation in hot electron-positron plasma is investigated. The possibility of finding localized stationary structures of EM waves is explored. It is shown that under certain conditions the EM wave forms a stable localized soliton-like structures where plasma is completely expelled from the region of EM field location. MIRAMARE TRIESTE August 1995 'Submitted to Physical Review E. 'Permanent address; University ofT ', inbul, Department of Physics, 34459, Vezneciler- Istanbul, Turkey. 3Present address: Faculty of Science, Hiroshima University, Hiroshima 739, Japan. Permanent address: Institute of Physics, The Georgian Academy of Science, Tbilisi 380077, Republic of Georgia. During the last few years a considerable amount of work has been de- voted to the analysis of nonlinear electromagnetic (EM) wave propagation in electron-positron (e-p) plasmas [I]. Electron- positron pairs are thought to be a major constituent of the plasma emanating both from the pulsars and from inner region of the accretion disks surrounding the central black holes in the active galactic nuclei (AGN) [2]. -

Mc2 " Mc2 , E = K + Mc2 = ! Mc2 for Particle of Charge Q and Mass M Moving in B Field : P = ! Mu = Qbr E2 = ( Pc)2 + (Mc2 )2

Department of Physics Modern Physics (2D) University of California Prof. V. Sharma San Diego Quiz # 3 (Jan 28, 2005) Some Relevant Formulae, Constants and Identities p = ! mu, K = ! mc2 " mc2 , E = K + mc2 = ! mc2 For particle of charge q and mass m moving in B field : p = ! mu = qBR E2 = ( pc)2 + (mc2 )2 In Photoelectric Effect E= hf = Kmax + # 23 Avagadro's Number NA = 6.022 $ 10 particles/mole Planck's Constant h=6.626 $ 10-34J.s=4.136 $ 10-15eV.s 1 eV = 1.602 $ 10-19 J -14 2 Electron rest mass = 8.2 $ 10 J = 0.511 MeV/c Proton rest mass = 1.673$ 10-27Kg = 938.3MeV/c2 Speed of Light in vaccum c = 2.998 $ 108m/s Electron charge = 1.602 $ 10-19 C Atomic mass unit u = 1.6605 $ 10-27kg = 931.49 MeV/c2 Please write your scratch work in pencil and write your answer in indelible ink in your Blue book. Please write your code number clearly on each page. Please plug in numbers only at the very end of your calculations. Department of Physics Modern Physics (2D) University of California Prof. V. Sharma San Diego Quiz # 3 (Jan 28, 2005) Problem 1: Weapons of Mass Destruction [10 pts] (a) How much energy is released in the explosion of a fission bomb containing 3.0kg of fissionable material? Assume that 0.10% of the rest mass is converted to released energy? (b) What mass of TNT would have to explode to provide the same energy release? Assume that each mole of TNT liberates 3.4MJ of energy on exploding. -

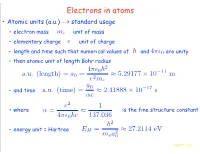

Electrons in Atoms • Atomic Units (A.U.) --> Standard Usage

Electrons in atoms • Atomic units (a.u.) --> standard usage – electron mass m e unit of mass – elementary charge e unit of charge – length and time such that numerical values of and 4 ⇥ 0 are unity – then atomic unit of length Bohr radius 2 4⇥0 11 a.u. (length) = a0 = 2 5.29177 10− m e me ⇥ × a0 17 – and time a.u. (time) = 2.41888 10− s αc ⇥ × e2 1 – where α = is the fine structure constant 4⇤⇥0c ≈ 137.036 2 – energy unit = Hartree EH = 2 27.2114 eV mea0 ≈ QMPT 540 Hamiltonian in a.u. • Most of atomic physics can be understood on the basis of N 2 N N pi Z 1 1 HN = + + Vmag 2 − ri 2 ri rj i=1 i=1 i=j | | | − | • for most applications V V eff = ζ s mag ⇥ so i i · i i • Relativistic description required for heavier atoms – binding sizable fraction of electron rest mass – binding of lowest s state generates high-momentum components • Sensible calculations up to Kr without Vmag • Shell structure well established QMPT 540 Shell structure • Simulate with N N H0 = H0(i) i=1 2 • with pi Z H0(i)= + U(ri) 2 − ri • even without auxiliary potential ⇒ shells (2 + 1) (2s + 1) – hydrogen-like: ∗ degeneracy Z2 ε = – but n − 2 n 2 does not give correct shell structure (2,10,28... – degeneracy must be lifted – how? QMPT 540 Effect of other electrons in neutral atoms • Consider effect of electrons in closed shells for neutral Na • large distances: nuclear charge screened to 1 • close to the nucleus: electron “sees” all 11 protons 0 • approximately: !5 !10 V(r) [a.u.] Sodium !15 !20 012345 r [a.u.] • lifts H-like degeneracy: ε2s < ε2p ε3s < ε3p < ε3d -

1 NANO 703-Notes Chapter 1-The Transmission Electron Microscope What Is TEM? TEM Can Stand for Either Transmission Electron Mi

1 NANO 703-Notes Chapter 1-The Transmission Electron Microscope What is TEM? TEM can stand for either transmission electron microscope (an instrument) or transmission electron microscopy (a technique). We will use both meanings in this course. First of all, why would we choose to use electrons instead of light to image nanomaterials? Electrons require high-vacuum conditions to propagate freely, and cannot be readily focused by our eyes. Visible light can travel trough air, as well as many transparent liquids and solids, and can be easily imaged by human eyes. What are electrons? We most often think of electrons as negatively charged, fundamental particles. They move quite freely inside conductors; that motion is the basis for all of our electrical power and electronic devices. The are very light, but not massless. But all particles also have a wave aspect, which implies a wavelength and frequency. Light can be thought of as electromagnetic waves, which have a wavelength and frequency, and which, when in a vacuum, propagate at the speed of light, not surprisingly. But light may be equivalently described as massless particles: photons. 1) Shorter wavelength: The wavelengths of both electrons and photons depend on their energy, but, since electrons have mass, while photons do not have mass, the wavelength of an electron is always less than that of a photon with the same energy. We will see that the imaging resolution of a microscope is highly dependent on the wavelength of the illuminating radiation (electrons or photons), due to diffraction effects, with shorter wavelengths resulting in higher resolving power (resolution of smaller features). -

Anomalous Magnetic Moment and Vortex Structure of the Electron

Anomalous magnetic moment and vortex structure of the electron S. C. Tiwari Department of Physics, Institute of Science, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi 221005, and Institute of Natural Philosophy Varanasi India The electron magnetic moment decomposition calculated in QED is proposed to have origin in a multi-vortex internal structure of the electron. This proposition is founded on two important contributions of the present work. First, a critical review on Weyl model of electron, Einstein- Rosen bridge and Wheeler’s wormholes leads to a new idea of a topological defect in cylindrical space-time geometry as a natural representation of the electron. A concrete realization of this idea in terms of the derivation of a new vortex-metric, and its physical interpretation to establish the geometric origin of the electron magnetic moment decomposition constitute the second contribution. Remarkable occurrence of a vortex structure in the basis mode function used in BLFQ is also pointed out indicating wider ramification of the proposed electron model. PACS numbers: 04.20.-q , 02.40.Ky, 11.15.Tk I. INTRODUCTION and the intrinsic magnetic moment vector µ has the z- component Recent discovery of the Higgs boson at LHC gives e¯h strong credence to the Standard Model (SM) of particle µ = = µB (1) ±2mc ± physics. The SM has withstood precision experimental tests carried out over past decades. The successful devel- In terms of g-factor, expression (1) implies that g = 2 for opment of the gauge theory of electro-weak sector, and the Dirac electron. Free electron magnetic moment mea- the advances in perturbative QCD methods combined sured using a one-electron quantum cyclotron [2], how- with near absence of new/exotic events at LHC make ever gives a different value the quest for unified theories beyond the SM superfluous g from the view-point of the empiricism/operationalism. -

Nuclear and Particle Physics 1

NuclearNuclear andand ParticleParticle PhysicsPhysics 11 (PHY211/281)(PHY211/281) HerbstsemesterHerbstsemester 20192019 OlafOlaf SteinkampSteinkamp 36-J-05 [email protected] 044 63 55763 Units We are dealing with the extremely small, e.g. typical length scale is “femtometer” 1 fm = 10–15 m KT1 HS19 Basics (2/21) O. Steinkamp ElectronVolt (eV) SI units not very well suited, e.g. → Electron charge e = 1.6 × 10–19 C –27 → Proton rest mass mp = 1.67 × 10 kg 2 –10 → Proton rest energy Ep = mp c = 1.5 × 10 J Define “electronVolt” (eV) as our basic unit of energy: energy gained by an electron moved across a potential of 1 V 1 eV = 1.6 × 10–19 J → Binding energy of electrons in atoms few eV → Proton rest mass 938 MeV (MeV = 106 eV) KT1 HS19 Basics (3/21) O. Steinkamp Natural Units Derived units Observable Unit in SI units Energy eV 1.60 × 10–19 J Mass E = mc2 eV / c2 1.78 × 10–36 kg Momentum E = pc eV / c 5.34 × 10–28 kg m/s Time ΔE Δt ≥ ℏ ℏ / eV 6.58 × 10–16 s Distance Δx Δp ≥ ℏ ℏc / eV 1.97 × 10–7 m KT1 HS19 Basics (4/21) O. Steinkamp Natural Units Often use “Natural units”, where c ≡ 1 and ℏ = h ≡ 1 2 π Natural Observable Unit in SI units unit Energy eV eV 1.60 × 10–19 J Mass E = mc2 eV / c2 eV 1.78 × 10–36 kg Momentum E = pc eV / c eV 5.34 × 10–28 kg m/s Time ΔE Δt ≥ ℏ ℏ / eV 1 / eV 6.58 × 10–16 s Distance Δx Δp ≥ ℏ ℏc / eV 1 / eV 1.97 × 10–7 m → Energy, mass and momentum have the same unit → Time and distance have the same unit KT1 HS19 Basics (5/21) O. -

The Mechanics of Electron-Positron Pair Creation in the 3-Spaces Model André Michaud SRP Inc Service De Recherche Pédagogique Québec Canada

International Journal of Engineering Research and Development e-ISSN: 2278-067X, p-ISSN: 2278-800X, www.ijerd.com Volume 6, Issue 10 (April 2013), PP. 36-49 The Mechanics of Electron-Positron Pair Creation in the 3-Spaces Model André Michaud SRP Inc Service de Recherche Pédagogique Québec Canada Abstract:- This paper lays out the mechanics of creation in the 3-spaces model of an electron-positron pair as a photon of energy 1.022 MeV or more is destabilized when grazing a heavy particle such as an atom's nucleus, thus converting a massless photon into two massive .511 MeV/c2 particles charged in opposition. An alternate process was also experimentally discovered in 1997, that involves converging two tightly collimated photon beams toward a single point in space, one of the beams being made up of photons exceeding the 1.022 MeV threshold. In the latter case, electron/positron pairs were created without any atom's nuclei being close by. These two observed processes of photon conversion into electron-positron pairs set the 1.022 MeV photon energy level as the threshold starting at which massless photons become highly susceptible to become destabilized into converting to pairs of massive particles. Keywords:- 3-spaces, electron-positron pair, 1.022 MeV photon, nature of mass, energy conversion to mass, materialization, sign of charges. I. EXPERIMENTAL PROOF OF ELECTRON-POSITRON PAIR CREATION In 1933, Blackett and Occhialini proved experimentally that cosmic radiation byproduct photons of energy 1.022 MeV or more spontaneously convert to electron/positron pairs when grazing atomic nuclei ([3]), a process that was named "materialization". -

On the Electrino Mass

On the Mass of the Electrino In this paper I estimate the mass of the electrino (new lepton) through two formulas. The first formula we shall explore is the lepto-baryonic formula for the fine-structure constant which I published in a previous paper entitled: Exponential Formula for the Fine Structure Constant. Unlike the formula presented there, this paper introduces an exact formula which is given as a function of the masses of the two lightest charged leptons: the electron and the electrino; and the lightest baryons: the neutron and the proton. The second formula we shall explore is the “alpha- 23” formula for the mass of the electron. Both formulas suggest the existence of a new super-light lepton which I have called: electrino. I predicted the existence of this particle in a previous paper entitled: Is the Electron Unstable?. This investigation suggests that the mass of the electrino, if this elusive particle exists, must have a value between me /529.3 and me /517.8 approximately. by Rodolfo A. Frino Keywords: fine-structure constant, mass ratio, lepton, baryon, neutrino, electrino, quark, NIST, GUT. 1. Introduction The exponential formula for the fine-structure constant given in my previous article [1] is α ≈ 2−18 ρ (1.1) where ρ is defined as the ratio me ρ ≡ (1.2) mn− m p (The nomenclature is included in Appendix 1). Combining equations (1.1) and (2.2) yields m −18 e (m n− m p ) 1 α ≈ 2 = (1.3) m 18 e (mn − m p ) 2 The value of the fine-structure constant given by this formula is α ≈ 0.007 229 708 17 while the value of this constant according to NIST (2010) [2] is α ≈ 0.007 297 352 569 8(24) . -

Physical Quantities That Are Sometimes Used As Units Alongside SI Units

Physical quantities that are sometimes used as units alongside SI units [Nematrian website page: FundamentalConstantsOfNatureUsedAsUnits, © Nematrian 2015] As explained in Introduction to SI units, physicists sometimes use quantities expressed in terms of fundamental constants of nature, alongside or instead of SI units. These fundamental constants include: Kind of quantity Physical quantity used as a unit measurement Commonly used symbol Speed speed of light in a vacuum 푐 [1] Action Planck constant divided by 2휋 ℏ = ℎ⁄(2휋) Mass electron rest mass 푚푒 electric charge elementary charge 푒 [2] Energy Hartree energy 퐸ℎ [3] Length Bohr radius 푎0 Time ratio of action to energy ℏ⁄퐸ℎ Notes: [1] ℏ is often also called the “reduced Planck constant” [2] The hartree or the Hartree energy (sometimes also referred to by the symbol Ha) is the atomic unit of energy and is defined as 2푅∞ℎ푐 where 푅∞ is the Rydberg constant, ℎ is the Planck constant and 푐 is the speed of light in a vacuum. It is approximately the electric potential energy of the hydrogen atom in its ground state and approximately twice its ionization energy (the relationships are not exact because of the finite mass of the nucleus of the hydrogen atom and relativistic corrections). It is usually used as a unit of energy in atomic physics and computational chemistry. For experimental measurements at the atomic scale the electron volt is more commonly used. It also satisfies the following relationships: 2 2 2 ℏ 푒 2 2 ℏ푐훼 퐸ℎ = 2 = 푚푒 ( ) = 푚푒푐 훼 = 푚푒푎0 4휋휖0ℏ 푎0 where ℏ is the reduced Planck constant, 푚푒 is the electron rest mass, 푒 is the elementary charge, 푎0 is the Bohr radius, 휖0 is the electric constant (i.e.