Viewer Toward Specific Reactions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alexis Pauline Gumbs (With Jeremiah Gumbs) Three Tries Alexis Pauline Gumbs the Story As I Remember It

Fishing Fly #2 THREE TRIES Alexis Pauline Gumbs (with Jeremiah Gumbs) three tries Alexis Pauline Gumbs the story as i remember it: Once upon a time in Anguilla there was a little boy named Jeremiah Gumbs. He was the youngest of nine children and they never had enough to eat. One day while little Jeremiah was out fishing with his friends he saw a beautiful rainbow fish. Beautiful, as in, delicious-looking. And big. The rainbow fish wasn’t big for no reason. The rainbow fish was wise and had grown large over the years by avoiding the hooks of the people who fished in the cove. The rainbow fish stayed safely beneath the edge of a rock watching. Keeping guard. But little Jeremiah was hungry. And he had a vision. He decided he would catch the rainbow fish and bring it home to his mother to cook for dinner. He prepared his pole and his line and his hook and tempted the rainbow fish with the most delectable bait he could charm from the grown fishermen. When he lowered the bait near the rainbow fish’s home rock he just knew he would be victorious. The rainbow fish smelled the bait and got curious. You know, fish get hungry too. The rainbow fish peered out from the edge of the rock, but the sun glinted off the edge of the sharp hook. The rainbow fish quickly swam back under the edge of the rock. No way. Not today. Jeremiah went home hungry. His mother fed him and his brothers and sisters with grease, salt tears, 2 three tries Alexis Pauline Gumbs and hard flour rolls left over from what she’d baked for the workers that morning. -

Rainbow Fish Discovers the Deep Sea Written and Illustrated by Marcus Pfister

IPS-ChildrensFall 3/20/09 2:55 PM Page 1 Contents Picture Books Cloth.....................................3 Ingram Publisher Services welcomes the following publishers Picture Books Paper..................................25 to our fine family of publishers: Novelty........................................................31 VeloPress Middle Reader and Young Adult...............43 ParentMap Bestselling Backlist...................................49 Index by Publisher.....................................74 To order, contact your Sales Representative or Index by Title..............................................76 call (866) 400-5351. Ingram Publisher Services 1 Ingram Blvd. La Vergne, TN 37086 IPS-ChildrensFall 3/20/09 2:55 PM Page 2 Picture Books Cloth IPS-ChildrensFall 3/20/09 2:56 PM Page 3 More than 30 million titles in the Rainbow Fish series sold worldwide. Rainbow Fish Discovers the Deep Sea written and illustrated by Marcus Pfister • Event kit with stickers and activity ideas available for back-to- school promotions. • Sparkling poster available for store display About the Book When the Rainbow Fish loses his last glittering scale, he is afraid to follow it into the depths of the deep sea. Summoning up his bravery, he makes the journey into the scary unknown, only to find an incredible new world and make wonderful new friends. Where the original Rainbow Fish taught children the importance of “Children will find the iridescent silver sharing, Rainbow Fish Discovers the Deep Sea teaches children not to be afraid highlights in the watercolor artwork of new situations and the joy of making new friends. beguiling and the emotions played out About the Author/Illustrator underwater familiar from the playground.” Marcus Pfister is the author of the phenomenally successful Rainbow Fish —Booklist series, as well as many other books for children. -

Field Guide 3 to 4

How to use the Building a Strong Foundation for School Success Series; Field Guide This field guide was created to offer an easy‐to‐read, practical supplement to the KY Early Childhood Standards (KYECS) for anyone who works with young children birth to four years old. This guide is intended to support early childhood professionals who work in the following settings: home settings, early intervention settings, and center‐based care. The field guide has chapters for each of the Kentucky Early Childhood Standards. Below is a description of the information you will find in each chapter. Each chapter will begin with a brief overview of the standard. In this paragraph, you will find information about what this standard is and the theory and research to support its use. Each chapter contains a section called Crossing Bridges. It is important to understand that the developmental domains of young children often cross and impact others. While a provider is concentrating on a young child learning communication skills, there are other domains or standards being experienced as well. This section tells the reader how this standard supports other standards and domains. For example, you will see that social emotional development of an infant supports or overlaps the infant’s communication development. Each chapter contains a section called Post Cards. This section offers supportive quotes about the standard. In this section, readers will also find narratives, written by early care providers for early care providers. These narratives provide a window into how the standard is supported in a variety of settings. Each chapter contains a section called Sights to See. -

Classes for Adults and Kids Notes Fall 2020

Art & Photography • Career & Technology Fitness • English Language Learners (ELL) • Food & Drink • Home & Garden Chess • Visual Arts & Crafts Science • Languages • Technology • and More... FALL 2020 classes for adults and kids notes fall 2020 adult classes IMAGINE– Art & Photography ....................................3 Business & Career ....................................27 What if someday… you could put on your pajamas, Computers & Technology ........................28 sit in your most comfortable chair, gather with Crafts.......................................................22 talented teachers and other eager learners, and Dance & Fitness .......................................16 immerse yourself in drawing, or computer program- ming, or in analyzing a 900-page novel you’ve always English Language Learners (ELL) .............30 10 wanted to read? You might even have your glass of Food & Drink ...........................................10 wine or bowl of oreo ice cream beside you… Home & Garden .......................................24 International Travel 2021 ........................22 Well, that day is now. This fall we are all online at Languages ................................................6 NCE, and we are embracing this opportunity. We had our metamorphosis this spring: after a very short Lifetime Learning ....................................30 period of going “dark”, we emerged with a robust Mind, Body, & Soul ..................................17 offering of spring and summer online classes for kids Money & Real Estate -

PB Packet 9.Pdf

Prison Bowl XIII: XIII Is Unlucky for a Reason Head edited by Rachel Yang. Vice head edited by Asher Jaffe. Section edited by Benjamin Chapman, Asher Jaffe, Ella Leeds, Pedro Juan Orduz, Cerulean Ozarow, Rachel Yang. Written by the Hunter College High School team (Asher Jaffe, Rachel Yang, Benjamin Chapman, Pedro Juan Orduz, Cerulean Ozarow, Ella Leeds, Aruna Das, Amanda Li, Alex Mazansky, Lindsey Shih, Daniel Shneider, Nicholas Wu, Andrew Zeng, Jacob Hardin-Bernhardt, Moxie Strom, Eamin Ahmed, Brian Chan, Ayan Kohli, Matthew Kohn, Maggie Kwan). Special thanks to Dr. Mike Cheyne, Robert Condron, Jordan Davidsen, Chloe Levine, Josh Rollin, and Conor Thompson for playtesting. PACKET NINE Tossups: 1. Édouard Drumont’s newspapers fanned public support against the main figure in this event. Antonio Panizzardi’s homosexual affair with Maximilian von Schwarzkoppen was used to discredit the main figure of this event. This event helped persuade Theodore Herzl to seek an independent (*) Jewish state in Palestine. L’Aurore newspaper was a strong supporter of one side in this scandal under the leadership of Georges Clemenceau. At the end of this scandal, Ferdinand Esterhazy was found to be the real culprit. Émile Zola’s “J’accuse” letter was published in—for 10 points—what French political scandal? ANSWER: Dreyfus affair [accept equivalents; accept l’affaire Dreyfus] <PO> 2. A sonnet by this author opens, “Tea leaves thwart those who court catastrophe,” and a poem composed of couplets by this writer includes the line “Perfection is terrible, it cannot have children.” The title poem of a collection by this poet of “Ennui” and “The Munich Mannequins” begins (*) “Stasis in darkness.” This poet wrote one poem which begins “I have done it again / One year in every ten / I manage it,” and ends “I rise with my red hair / And I eat men like air.” This poet tells her title family member in one poem “You do not do, you do not do” and ends the poem “You bastard, I’m through.” For 10 points, name this poet of “Lady Lazarus” and “Daddy.” ANSWER: Sylvia Plath <RY> 3. -

Northern Edition

Chantilly ❖ Fair Oaks ❖ Fair Lakes ❖ Oak Hill NORTHERN EDITION DECEMBER 27 - JANUARY 2, 2012 25 CENTS Newsstand Price Children’sChildren’s CentreCentre ViewView Annie- Sophie Kim, grade 12, Chantilly 20122012 High School www.ConnectionNewspapers.com Centre View North ❖ Children’s Centre View ❖ 2012 - 2013 ❖ 1 Throw a great birthday party for your little one! Franklin Middle School We put the ART in Party! • FUN • AFFORDABLE • EASY • SPACIOUS FUN FOR ALL AGES! call 703.817.1051 or visit www.claycafechantilly.com 13894 Metrotech Dr. • Chantilly (Just to the left of Petsmart) Arborvitae,Trees,Trees, Select Hollies Helen Shi, grade 7 Samantha Aguero, grade 7 Katerina Bagatska, grade 7 Camelias, 25%35%25% Writings ShrubsShrubsAzaleas and && 50% Off OFFOFF PerennialsPerennialsShade Trees Cleveland Pears Just Me Kennebunkport, OFF-SEA My mind is a maze, a mental puzzle PRICING that tests all forms of knowledge. 50-65% Off Pottery FREE SON Maine Washington Area’s BiggestBiggest SelectionSelection Landscape & My imagination is undrawn scenery, Boing! A lobster buoy sounds in the surrounds me, yet, no one else can see distance. Hardscape Estimates it. 30% OFF Japanese Maples •Patios•Walls•Walkways Plop! A fish flops in the ocean. My hair is like a horse’s mane, long Sizzle! A burger is flipped on a grill. or Buy 1 Get 1 Free* •Paver Driveways and thick. Crunch! Crunch! Gravel under *Off regular price •RR Timber Retaining Walls My creativity is a pillow, stuffed with people’s walking feet. a thousand feathers, waiting, wanting, Splash! Children play in the water. 9023 Arlington Blvd., to burst at the seams. -

The Brhat-Sanhitâ, Or Complete System of Natural Astrology

ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY or GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND. THE BRHAT-SANHITA, OB, COMPLETE SYSTEM OF NATURAL ASTROLOGY OF YARAHA-MIHIRA .y TRANSLATED FROM SANSKRIT INTO ENGLISH. BY Dr. U . KERN. « (c " I V .R 'i^ V A . Digitized by G o o g le 1 Sir- THE BKHAT-SAHHITi: / • O»* COMPLETE SYSTEM OF NATURAL ASTROLOGY OF YA'RJiTTA.V 1HTRA, TRANSLATED FROM SANSKRIT INTO ENGLISH. B r Db. H. KEEN. I C h a p t e r L Introduction. 1. Victory to the Allsoul, the source of life, the inseparable ornament of heaven, the Sun, who is adorned with a crown o f a thousand beams like unto liquid gold I 2. After studying the subject matter which former Seers1 have revealed with infallible truth, I purpose to treat of the same in an easy style, and in verses neither too few nor too m any. 3. Should any one think that an ancient work, as being made by Seers, is good, and that a book by a human author is not, (then I would fain ask) what difference it makes in the statement, however different the wording may be, if the thing told remain the same?* The Holy W rit,is hers exoepted. 1 The commentator, Utpala, takes ITgq q fil as «the first tear, vis. Brahma,* bat W p T O X » 001 being identical with 1|T4j|P| W U points to a plurality of infallible authors, although it is true that Brahma, the Creator, is, o f coarse, the very Erst astronomer In the Hinds system. -

Brian P Cleary a Children's History of India (Plastic) a Child's First

THE DEN A A Cat a Bat Your Grandma’s Hat - Brian P Cleary A Children’s History of India (plastic) A Child's first Reading Program : Level 1 to Level 10 ( 10 books) A Dragon on the doorstep - Stella Blackstone A Dome for a Home - Ruth Martin Academic’s 21st century - Volume 1 Academic’s 21st century - Volume 1 Adventures with Dora - storybook and electronic picture dictionary Aesop’ Fables - Early Readers Aesop’ Fables - Enchanting Tales Ahmed and the Feather Girl - Jane Ray Aiyappan & The Magic Horse - P. Rajagopal, Evelien Pullens, Hanns M. de Bruin A felt Fun world of Little Friends - Baby Animals All Aboard - Bianca Lucas All About Nothing - Nina Serbian A Letter to Santa - Janet Craig A letter to Santa - Gaby Goldsack Alfie : Alfie’s feet - Shirley Hughes Alfie and the Birthday Suprise All Together Now - Pandit Vishnu Sharma All Kinds of Friends - Pooh Alexander and the Wind-Up Mouse - Leo Lionni A Lion in Paris - Beatrice Alleging Alice in Wonderland - Lady bird - Louis Carol Alice in Wonderland - Louis Carol Aliens Love Underpants - Claire Freedman & Ben Cort Amazing Grace - Mary Hoffman & Caroline Bench Ambulance - Lift the giant flap book Amelia Jane Again - Enid Blyton Amelia Jane Is Naughty Again - Enid Blyton A Moose in the House - Matthew Fit & James Robertson Amazing Spot What - Nick Bryant & Roman Summers Anna and China - Sowmya Rajendra Angelina, Star of the Show - Katharine Holabird And Land Was Born - Sandhya Rao Andamans Boy - Zai Whitaker Animals Animals -Eric Carle Animal Music - Julia Donaldson & Nick Sharratt Animal -

The Phenomenon of Preschool Children's

THE PHENOMENON OF PRESCHOOL CHILDREN’S SPIRITUALITY . A thesis presented for the requirement for PhD, Doctor of Philosophy at Queensland University of Technology By Anna Giesenberg DipKGT, B.Ed.E.Ch, M.Ed. Supervisor: Associate Professor Dr John Lidstone Associate Supervisor: Dr Peter Bond Anna Giesenberg, 2007 Giesenberg, Anna (2007) “The Phenomenology of Preschool Children’s Spirituality” An abstract of a PhD study looking at young children’s spirituality. School of Cultural and Language Studies in Education, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia. Spirituality is discussed as seen in literature from the disciplines of psychology, religion, education, nursing, politics and philosophy. Special emphasis is placed on how spirituality is viewed in regard to young children. From the disciplines mentioned, an overall definition of spirituality – at least for adults - is derived: “Spirituality is an innate ability to show awareness or consciousness of the surrounding world shown through wonder, a sense of compassion, and love towards this world and everything in it, and for some people a relationship with a transcendent being, who can also be immanent in the individual.” Findings are described from a field study of 12 months duration where 56 children, aged 3-7 years, from 4 different early childhood settings were followed on a fortnightly basis. The children were able to express aspects of spirituality in their play, discussions and artwork, such as paintings and drawings. The children were asked to paint and draw their experiences of selected pieces of chamber music, of a beautiful day, of love, and of dreams. In addition children were observed in their interactions with peers. -

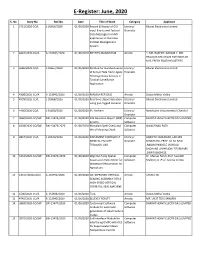

E-Register: June, 2020

E-Register: June, 2020 S. No. Diary No. RoC No. Date Title of Work Category Applicant 1 3721/2020-CO/L L-91666/2020 01/06/2020 Record & Replay of GUI Literary/ Bharat Electronics Limited input Events and Tactical Dramatic Data Messages for HMI application in Maritime Combat Management System 2 4447/2020-CO/A A-133941/2020 01/06/2020 MELTIES MANGO FUN Artistic 1. MR. RAKESH LAKHANI 2. MR. PRAVEEN KHETWANI PARTNERS OF M/S. FRESH FOOD INDUSTRIES 3 3686/2020-CO/L L-91667/2020 01/06/2020 Method for Standardization Literary/ Bharat Electronics Limited of Sensor Data from Legacy Dramatic Heterogeneous Sensors in Tactical Surveillance Application 4 4398/2020-CO/A A-133942/2020 01/06/2020 MASALA REPUBLIC Artistic Dadus Mithai Vatika 5 4579/2020-CO/L L-91668/2020 01/06/2020 Real time Object detection Literary/ Bharat Electronics Limited using geo-tagged cameras Dramatic 6 4466/2020-CO/L L-91669/2020 01/06/2020 IPL Anthem Literary/ Neethusha Vaisiamveettil Cherckal Dramatic 7 3660/2020-CO/SW SW-13474/2020 01/06/2020 Site Deviation Report (SDR) Computer BHARAT HEAVY ELECTRICALS LIMITED System Software 8 4328/2020-CO/SW SW-13475/2020 01/06/2020 Malyalam Spell Check and Computer NIVAS BHAU PATIL Word Meaning Check Software 9 2837/2020-CO/L L-91670/2020 01/06/2020 IMPLEMENT EMERGENCY Literary/ ANIKET KHANORKAR ,LAKHAN MEDICAL FACILITY Dramatic MANGTANI ,PROF. M. M. BAIG THROUGH UAV ,RAJANI PANDELE ,RUSHALI BADHANE ,SAMRUDHI TITARMARE ,SWATI BAGHELE 10 3452/2020-CO/SW SW-13476/2020 01/06/2020 Wighted Fuzzy Spatial Computer Dr. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. NCTE Bibliography

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 362 878 CS 214 064 AUTHOR Jensen, Julie M., Ed.; Roser, Nancy L,, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Tenth Edition. NCTE Bibliography Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0079-1; ISSN-1051-4740 PUB DATE 93 NOTE 682p.; For the previous edition, see ED 311 453. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 00791-0015; $14.95 members, $19.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) -- Books (010) EDRS PRICE MF04/PC28 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; *Childrens Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Mathematical Concepts; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Material Selection; *Recreational Reading; Scientific Concepts; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Eastorical Fiction; Trade Books ABSTRACT Designed to help teachers, librarians, arid parents introduce books of exceptional literary and artistic merit, accuracy, and appeal to preschool through sixth grade children, this annotated bibliography presents nearly 1,800 annotations of approximately 2,000 books (2 or more books in a series appear in a single review) published between 1988 and 1992. Annotations are grouped under 13 headings: Biography; Books for Young Children; Celebrations; Classics; Contemporary Realistic Fiction; Fantasy; Fine Arts; Historical Fiction; Language and Reading; Poetry; Sciences and Mathematics, Social Studies; and Traditional Literature. In addition to the author and title, each annotation lists illustrators where applicable and the recommended age range of potential readers. A selected list of literary awards given to children's books published between 1988 and 1992; a description of popular booklists; author, illustrator, subject, and title indexes; and a directory of publishers are attached.