Beatrice's World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taste Abbeyseng

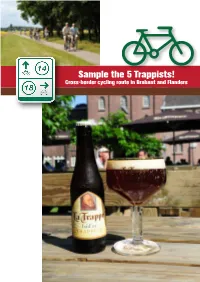

Sample the 5 Trappists! Cross-border cycling route in Brabant and Flanders The Trappist region The Trappist region ‘The Trappists’ are members of the Trappist region; The Trappist order. This Roman Catholic religious order forms part of the larger Cistercian brotherhood. Life in the abbey has as its motto “Ora et Labora “ (pray and work). Traditional skills form an important part of a monk’s life. The Trappists make a wide range of products. The most famous of these is Trappist Beer. The name ‘Trappist’ originates from the French La Trappe abbey. La Trappe set the standards for other Trappist abbeys. The number of La Trappe monks grew quickly between 1664 and 1670. To this today there are still monks working in the Trappist brewerys. Trappist beers bear the label "Authentic Trappist Product". This label certifies not only the monastic origin of the product but also guarantees that the products sold are produced according the traditions of the Trappist community. More information: www.trappist.be Route booklet Sample the 5 Trappists Sample the 5 Trappists! Experience the taste of Trappist beers on this unique cycle route which takes you past 5 different Trappist abbeys in the provinces of North Brabant, Limburg and Antwerp. Immerse yourself in the life of the Trappists and experience the mystical atmosphere of the abbeys during your cycle trip. Above all you can enjoy the renowned Brabant and Flemish hospitality. Sample a delicious Trappist to quench your thirst or enjoy the beautiful countryside and the towns and villages with their charming street cafes and places to stay overnight. -

The Architecture of Miracle- Working Statues in the Southern Netherlands

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Ghent University Academic Bibliography MAARTEN DELBEKE LISE CONSTANT Universiteit Gent / Universiteit Leiden Universiteit Gent / Université catholique de Louvain LOBKE GEURS ANNELIES STAESSEN Universiteit Gent Universiteit Gent The architecture of miracle- working statues in the Southern Netherlands In the 17th century, the Southern Netherlands saw the erection or restoration of numerous sanctuaries dedicated to the Virgin Mary. In many cases, they housed a miracle- working statue. This essay analyzes the architecture of these sanctuaries through the histories that were written about their statues. It examines how the history of the statues, as recorded in contemporary textual and visual sources, represents and interprets their material surroundings, including the architecture, in order to understand how the statues were thought to relate to these surroundings. Three types of historical narratives are distinguished, each explaining the presence and actions of a statue on its site. These three types will, in turn, shed light on the characteristics and development of the material surroundings of the miracle- working s tatues. L’architecture des statues miraculeuses dans les Pays- Bas méridionaux Au XVIIe siècle, les Pays- Bas méridionaux voient la construction ou la restauration de nombreux sanctuaires dédiés à la Vierge qui, pour la plupart, abritent une statue miraculeuse. Cet essai analyse l’architecture de ces sanctuaires à partir des récits écrits sur ces statues. Il examine comment l’histoire des statues, enregistrée dans les sources textuelles et iconographiques contemporaines, représente et interprète leur environnement matériel, incluant l’architecture, afi n de comprendre le lien que ces statues étaient supposées entretenir avec ce cadre. -

Download: Brill.Com/Brill-Typeface

The Matter of Piety Studies in Netherlandish Art and Cultural History Editorial Board H. Perry Chapman (University of Delaware) Yannis Hadjinicolaou (University of Hamburg) Tine Meganck (Vrije Universiteit Brussel) Herman Roodenburg (Formerly Meertens Institute and Free University Amsterdam) Frits Scholten (Rijksmuseum and University of Amsterdam) Advisory Board Reindert Falkenburg (New York University) Pamela Smith (Columbia University) Mariët Westermann (New York University) VOLUME 16 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/nach The Matter of Piety Zoutleeuw’s Church of Saint Leonard and Religious Material Culture in the Low Countries (c. 1450-1620) By Ruben Suykerbuyk LEIDEN | BOSTON Publication of this book has been aided by Ghent University and the Research Foundation – Flanders (FWO). This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Cover illustration: Anonymous, Saint Leonard, c. 1350–1360, Zoutleeuw, church of Saint Leonard (© KIK-IRPA, Brussels). The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2020022180 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. -

Metropolis and Hinterland? a Comment on the Role of Rural Economy and Society in the Urban Heart of the Medieval Low Countries1

bmgn - Low Countries Historical Review | Volume 127-2 (2012) | pp. 82-88 Metropolis and Hinterland? A Comment on the Role of Rural Economy and Society in the Urban Heart of the Medieval Low Countries1 tim soens, eline van onacker and kristof dombrecht Urbanity was a distinguishing feature of the medieval Low Countries, but even in its most urbanised core a majority of the population continued to live outside the city walls. In his new and encompassing synthesis of the history of the Low Countries in the later Middle Ages, Wim Blockmans emphasises the fundamental intertwining of urban and rural societies in this region, but also the existing historiographical gap between urban and rural historians. This contribution pleads for a reconsideration of the impact of urbanisation and urbanity on rural society as a whole, exemplified for instance, by the role of urban demand as a driving force in the rural economy or by the spread of an ‘urban-modelled’ civic life beyond the city walls. Although every village community was in one way or another connected to the urban world, villages were not entirely shaped by the latter and striking regional differences in both economic development, social cohesion and political organisation persisted well beyond the medieval period. In order to explain these differences the endogenous dynamics of rural societies have to be taken into account. Introduction: the urban shadow With his recent book, Metropolen aan de Noordzee, Wim Blockmans truly has created a monument for the urban society of the Low Countries in the later Middle Ages. According to Blockmans, ‘urbanity’ became the dominant feature of this region. -

Beyond the Flock. Sheep Farming, Wool Sales and Social Differentiation in a Sixteenth-Century Peasant Society: the Campine in the Low Countries*

Beyond the flock. Sheep farming, wool sales and social differentiation in a sixteenth-century peasant society: the Campine in the Low Countries* beyond the flock by Maïka De Keyzer and Eline Van Onacker Abstract In the existing literature late medieval sheep keeping has been perceived as a landlord and tenant- farmer strategy, aimed at international export markets. In this article we want to show that there was another side to those activities. Up until the early modern period, some regions – such as the Campine district in the Low Countries – managed to maintain viable peasant sheep-breeding enterprises. Two things were vital for the survival of peasant sheep breeding in the Campine. First of all the specific social structure and power structure of the region, allowing the peasants to keep control over their common lands and use them for their own (commercial) strategies. And secondly, there were lively local and regional markets, where demand for lower quality textiles was and remained strong. The late medieval Low Countries were especially renowned as a centre of cloth production. Their original fame came from the luxurious ‘Old Draperies’ (gesmoutte draperie), and later from the cheaper ‘New Draperies’. But in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the much cheaper ‘light drapery’ or ‘dry drapery’ – of which the Hondschoote saies were perhaps most famous – increasingly flooded the markets of Europe and the New World. Historiography on these export-driven industries is extensive,1 as is research on the production of wool for the old draperies.2 The literature tends to concentrate on the supply of high-quality wool, imported * This research was funded by ERC Advanced Grant no. -

Belgium Section 17: Cultural Institutions

oUTZ ARMY SERVICE FORCES MANUAL Li-Mi~3 -- ----- ~-CI---~-r - -- P~----9 I---ICI-------- CIVIL AFFAIRS HANDBOOK BELGIUM SECTION 17: CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS -----~- -- -c- = -- III" --~--~-~-~e p~-- IC~ Dissemination of restricted matter. - The information con- tained in restricted documents and the essential characteristics of restricted material may be given to any person known to be in the service of the United States and to persons of undoubted loyalty and discretion who are cooperating in Government work, but will not be communicated to the public or to the press except by authorized military public relations agencies. (See also par. 18b, AR 380-5, 28 Sep 1912.) HEADQUARTERS. ARMY SERVICE FORCES. 13 MAY 1t944 ARMY SERVICE FORCES MANAL M361-17 Civil Affairs -- - I - - - I -II I CIVIL AFFAIRS HANDBOOK BELGIUM SECTION 17: CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS - - ~e~-~P~--~CC --- L- C- - II I - - --- - - - - HEADQUARTERS, ARMY SERVICE FORCES, 13 MAY 1944 * * Dissemination of restricted matter. - The information con- tained in restricted documents and the essential characteristics of restricted material may be given to any person known to be in the service of the United States and to persons of undoubted loyalty and discretion who are cooperating in Government work, but will not be communicated to the public or to the press except by authorized military public relations agencies. (See also par. 18b, AR 380-5, 28 Sep 1942.) - ii - NUMBERING SYSTEM OF ARMY SERVICE FORCES MANUALS The main subject matter of each Army Service Forces Manual is indicated by consecutive numbering within the following categories: Ml- M99 Basic and Advanced Training Mdo0 - M199 Army Specialized Training Program and Pre- Induction Training M200 -. -

Observantiae Continuity and Reforms in the Cistercian Family

Observantiae Continuity and Reforms in the Cistercian Family 2 This programme has been written for the Communities of the Cistercian Family. and for this purpose, It can be freely copied and translated for this purpose. For any other use, all rights are reserved. Rome, September 14th 2002 3 Observantiae Continuity and Reforms in the Cistercian Family Observantiae : Introduction (Dom Bernardo Olivera) …………… 5 Prologue : To familiarise ourselves with the word « Observances » and to make the link with the Exordium programme ……………… 9 1° part : Necessary adaptations in a wished for continuation 1. Cistercian development in the 12th and 13th Centuries …………….21 2. Continuity and Reforms from 12 th to 15 th century ……………… 31 3. The Cistercian Congregations in the Iberian Peninsula……..… 40 4. History of the Cistercian Congregation of Upper Germania……… 47 2° part : Reformers searching an authentic renewal 5. The Birth of the Strict Observance……………………………… 55 6. A generation of Reforming Women…………………… ………… 70 7. Port-Royal………………………………………….………………… 75 8. The Bernardines of Switzerland……….…………………………… 84 9. The Abbot de Rancé and La Trappe in the 17 th century……… 90 3° part : Growing diversity in an often heroic fidelity 10. Cistercian Life in the Century of Enlightment (18 th century) 101 11. French Monasticism during the Revolution , the saga of Dom Augustine de Lestrange …………………………………………… 105 12. Bernardines of Esquermes…………………………..…………….. 118 13. The Cistercian Congregations in Italy…….…………………….. 126 14. Cistercian Congregations in the 19 th century…….………….. 140 15. The Trappist-Cistercians during the 19 th century……………… 150 16. Cistercian Foundations outside of Europe in the 19 th century. 160 General Bibliography …………………………………………….. 165 4 5 OBSERVANTIAE At the time we were closing the Regional Meeting of FSO at Chambarand, in 1999, I was asked to share my views on the Region.