NYRA-Vs-Baffert-Ruling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the News – State Governor Breaks Ground on New Belmont Park Arena

This Week In New York/Page 1 This Week in New York Covering New York State and City Government A Publication of Pitta Bishop & Del Giorno LLC September 27, 2019 Edition Shanah Tovah from Pitta Bishop & Del Giorno LLC In the News – State Governor Breaks Ground on New Belmont Park Arena Governor Andrew Cuomo joined the New York Islanders, National Hockey League Commissioner Gary Bettman, local leaders and hockey fans to break ground on the New York Islanders' new arena at Belmont Park, the centerpiece of the $1.3 billion Belmont Park Redevelopment. In addition, Governor Cuomo announced the team has agreed to play 28 regular season games at the Nassau Veteran's Memorial Coliseum during the 2019-2020 season, seven more than previously planned. {00665744.DOCX / }Pitta Bishop & Del Giorno LLC, 111 Washington Avenue, Albany, New York. (518) 449-3320 Theresa Cosgrove, editor, [email protected] This Week In New York/Page 2 "The Islanders belong on Long Island — and today we start building the state-of-the-art home this team and their fans deserve while generating thousands of jobs and billions in economic activity for the region's economy," Governor Cuomo said. "With seven more Islanders games at the Coliseum this season, fans will have even more opportunities to see their favorite team and generate momentum for the move to their new home in two years. At the end of the day this project is about building on two great Long Island traditions - Belmont Park and the Islanders - and making them greater than ever." Announced in December 2017, the Belmont Redevelopment Project will turn 43 acres of underutilized parking lots at Belmont Park into a premier sports and hospitality destination, including a new 19,000-seat arena for the New York Islanders hockey team and other events, a 250-key hotel, a retail village and office and community space. -

Aqueduct Racetrack Is “The Big Race Place”

Table of Contents Chapter 1: Welcome to The New York Racing Association ......................................................3 Chapter 2: My NYRA by Richard Migliore ................................................................................6 Chapter 3: At Belmont Park, Nothing Matters but the Horse and the Test at Hand .............7 Chapter 4: The Belmont Stakes: Heartbeat of Racing, Heartbeat of New York ......................9 Chapter 5: Against the Odds, Saratoga Gets a Race Course for the Ages ............................11 Chapter 6: Day in the Life of a Jockey: Bill Hartack - 1964 ....................................................13 Chapter 7: Day in the Life of a Jockey: Taylor Rice - Today ...................................................14 Chapter 8: In The Travers Stakes, There is No “Typical” .........................................................15 Chapter 9: Our Culture: What Makes Us Special ....................................................................18 Chapter 10: Aqueduct Racetrack is “The Big Race Place” .........................................................20 Chapter 11: NYRA Goes to the Movies .......................................................................................22 Chapter 12: Building a Bright Future ..........................................................................................24 Contributors ................................................................................................................26 Chapter 1 Welcome to The New York Racing Association On a -

Jockey Records

JOCKEYS, KENTUCKY DERBY (1875-2020) Most Wins Jockey Derby Span Mts. 1st 2nd 3rd Kentucky Derby Wins Eddie Arcaro 1935-1961 21 5 3 2 Lawrin (1938), Whirlaway (’41), Hoop Jr. (’45), Citation (’48) & Hill Gail (’52) Bill Hartack 1956-1974 12 5 1 0 Iron Liege (1957), Venetian Way (’60), Decidedly (’62), Northern Dancer-CAN (’64) & Majestic Prince (’69) Bill Shoemaker 1952-1988 26 4 3 4 Swaps (1955), Tomy Lee-GB (’59), Lucky Debonair (’65) & Ferdinand (’86) Isaac Murphy 1877-1893 11 3 1 2 Buchanan (1884), Riley (’90) & Kingman (’91) Earle Sande 1918-1932 8 3 2 0 Zev (1923), Flying Ebony (’25) & Gallant Fox (’30) Angel Cordero Jr. 1968-1991 17 3 1 0 Cannonade (1974), Bold Forbes (’76) & Spend a Buck (’85) Gary Stevens 1985-2016 22 3 3 1 Winning Colors (1988), Thunder Gulch (’95) & Silver Charm (’98) Kent Desormeaux 1988-2018 22 3 1 4 Real Quiet (1998), Fusaichi Pegasus (2000) & Big Brown (’08) Calvin Borel 1993-2014 12 3 0 1 Street Sense (2007), Mine That Bird (’09) & Super Saver (’10) Victor Espinoza 2001-2018 10 3 0 1 War Emblem (2002), California Chrome (’14) & American Pharoah (’15) John Velazquez 1996-2020 22 3 2 0 Animal Kingdom (2011), Always Dreaming (’17) & Authentic (’20) Willie Simms 1896-1898 2 2 0 0 Ben Brush (1896) & Plaudit (’98) Jimmy Winkfield 1900-1903 4 2 1 1 His Eminence (1901) & Alan-a-Dale (’02) Johnny Loftus 1912-1919 6 2 0 1 George Smith (1916) & Sir Barton (’19) Albert Johnson 1922-1928 7 2 1 0 Morvich (1922) & Bubbling Over (’26) Linus “Pony” McAtee 1920-1929 7 2 0 0 Whiskery (1927) & Clyde Van Dusen (’29) Charlie -

Governor Andrew M. Cuomo to Proclaim MEMORIALIZING June 5

Assembly Resolution No. 347 BY: M. of A. Solages MEMORIALIZING Governor Andrew M. Cuomo to proclaim June 5, 2021, as Belmont Stakes Day in the State of New York, and commending the New York Racing Association upon the occasion of the 152nd running of the Belmont Stakes WHEREAS, The Belmont Stakes is one of the most important sporting events in New York State; it is the conclusion of thoroughbred racing's prestigious three-contest Triple Crown; and WHEREAS, Preceded by the Kentucky Derby and Preakness Stakes, the Belmont Stakes is nicknamed the "Test of the Champion" due to its grueling mile and a half distance; and WHEREAS, The Triple Crown has only been completed 12 times; the 12 horses to accomplish this historic feat are: Sir Barton, 1919; Gallant Fox, 1930; Omaha, 1935; War Admiral, 1937; Whirlaway, 1941; Count Fleet, 1943; Assault, 1946; Citation, 1948; Secretariat, 1973; Seattle Slew, 1977; Affirmed, 1978; and American Pharoah, 2015; and WHEREAS, The Belmont Stakes has drawn some of the largest sporting event crowds in New York history, including 120,139 people for the 2004 running of the race; and WHEREAS, This historic event draws tens of thousands of horse racing fans annually to Belmont Park and generates millions of dollars for New York State's economy; and WHEREAS, The Belmont Stakes is shown to a national television audience of millions of people on network television; and WHEREAS, The Belmont Stakes is named after August Belmont I, a financier who made a fortune in banking in the middle to late 1800s; he also branched out -

Kentucky Derby, Flamingo Stakes, Florida Derby, Blue Grass Stakes, Preakness, Queen’S Plate 3RD Belmont Stakes

Northern Dancer 90th May 2, 1964 THE WINNER’S PEDIGREE AND CAREER HIGHLIGHTS Pharos Nearco Nogara Nearctic *Lady Angela Hyperion NORTHERN DANCER Sister Sarah Polynesian Bay Colt Native Dancer Geisha Natalma Almahmoud *Mahmoud Arbitrator YEAR AGE STS. 1ST 2ND 3RD EARNINGS 1963 2 9 7 2 0 $ 90,635 1964 3 9 7 0 2 $490,012 TOTALS 18 14 2 2 $580,647 At 2 Years WON Summer Stakes, Coronation Futurity, Carleton Stakes, Remsen Stakes 2ND Vandal Stakes, Cup and Saucer Stakes At 3 Years WON Kentucky Derby, Flamingo Stakes, Florida Derby, Blue Grass Stakes, Preakness, Queen’s Plate 3RD Belmont Stakes Horse Eq. Wt. PP 1/4 1/2 3/4 MILE STR. FIN. Jockey Owner Odds To $1 Northern Dancer b 126 7 7 2-1/2 6 hd 6 2 1 hd 1 2 1 nk W. Hartack Windfields Farm 3.40 Hill Rise 126 11 6 1-1/2 7 2-1/2 8 hd 4 hd 2 1-1/2 2 3-1/4 W. Shoemaker El Peco Ranch 1.40 The Scoundrel b 126 6 3 1/2 4 hd 3 1 2 1 3 2 3 no M. Ycaza R. C. Ellsworth 6.00 Roman Brother 126 12 9 2 9 1/2 9 2 6 2 4 1/2 4 nk W. Chambers Harbor View Farm 30.60 Quadrangle b 126 2 5 1 5 1-1/2 4 hd 5 1-1/2 5 1 5 3 R. Ussery Rokeby Stables 5.30 Mr. Brick 126 1 2 3 1 1/2 1 1/2 3 1 6 3 6 3/4 I. -

Eclipse Special Edition

Gamine Gives Sire A Second Winner... 'TDN Rising Star' Essential Quality (Tapit) did his part, ripping Michael Lund's 'TDN Rising Star' Gamine (Into Mischief) was through his competition in three starts and clinching the Eclipse something of a lightning rod in 2020, but she possessed arguably Award as champion 2-year-old male with a sizzling finish in the the most raw ability of any horse in training and while she GI Breeders' Cup Juvenile. Monomoy Girl (Tapizar) won her finished a distant runner-up to Swiss Skydiver in the 3-year-old second Eclipse Award in the last three years, adding to her filly category, she easily 3-year-old filly championship outdistanced Serengeti with the 2020 Eclipse as Empress (Alternation) to take champion older female. home the Eclipse for champion Purchased by Spendthrift for female sprinter. The $220,000 $9.5 million at Fasig-Tipton Keeneland September yearling November, the chestnut is turned $1.8-million Fasig- nearing her 6-year-old debut. Tipton Midlantic topper Other Wide-Margin became the second straight daughter of Into Mischief to Winners... both win the GI Breeders' Cup Vequist (Nyquist) provided Filly & Mare Sprint en route to her sire from his very first crop a championship following on to the races, securing the the exploits of Covfefe in 2019. Eclipse as champion 2-year-old Trainer Bob Baffert had his filly on the strength of hands on a third Eclipse winner victories in the GI Spinaway S. for 2020 in the form of 'TDN Gamine | Sarah Andrew in September before turning Rising Star' Improbable (City Zip). -

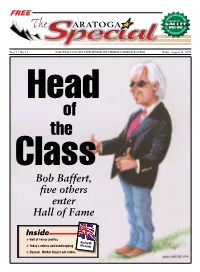

Bob Baffert, Five Others Enter Hall of Fame

FREE SUBSCR ER IPT IN IO A N R S T COMPLIMENTS OF T !2!4/'! O L T IA H C E E 4HE S SP ARATOGA Year 9 • No. 15 SARATOGA’S DAILY NEWSPAPER ON THOROUGHBRED RACING Friday, August 14, 2009 Head of the Class Bob Baffert, five others enter Hall of Fame Inside F Hall of Famer profiles Racing UK F Today’s entries and handicapping PPs Inside F Dynaski, Mother Russia win stakes DON’T BOTHER CHECKING THE PHOTO, THE WINNER IS ALWAYS THE SAME. YOU WIN. You win because that it generates maximum you love explosive excitement. revenue for all stakeholders— You win because AEG’s proposal including you. AEG’s proposal to upgrade Aqueduct into a puts money in your pocket world-class destination ensuress faster than any other bidder, tremendous benefits for you, thee ensuring the future of thorough- New York Racing Associationn bred racing right here at home. (NYRA), and New York Horsemen, Breeders, and racing fans. THOROUGHBRED RACING MUSEUM. AEG’s Aqueduct Gaming and Entertainment Facility will have AEG’s proposal includes a Thoroughbred Horse Racing a dazzling array Museum that will highlight and inform patrons of the of activities for VLT REVENUE wonderful history of gaming, dining, VLT OPERATION the sport here in % retail, and enter- 30 New York. tainment which LOTTERY % AEG The proposed Aqueduct complex will serve as a 10 will bring New world-class gaming and entertainment destination. DELIVERS. Yorkers and visitors from the Tri-State area and beyond back RACING % % AEG is well- SUPPORT 16 44 time and time again for more fun and excitement. -

Sweezey Following

ftboa.com • Tuesday & Wednesday • Dec 15 & 16, 2020 FEC/FTBOA PUBLICATION FLORIDA’SDAILYRACINGDIGEST FOR ADVERTISING Sweezey Following INFORMATION or to subscribe, please call ‘Jerkens Way’ to Antoinette at 352-732-8858 or Success at Gulfstream email: [email protected] Former Jimmy Jerkens Assistant Making Most of Opportunities In This Issue: PRESS RELEASE _________________ Lenzi’s Lucky Lady Wins Co-Feature at HALLANDALE BEACH, FL—Falling back Gulfstream Park on the knowledge he gained while serv- ing as an assistant to trainer Jimmy Bellocq and Leggett Selected For Joe Jerkens’ for three years, J. Kent Sweezey Hirsch Media Roll of Honor has been making a name for himself while competing in South Florida on a Journeyman Joyce Rides First Winner in year-round basis for the first time this Nearly Seven Years year. “We’re doing old school stuff with the Eagle Orb Looks to Step Up in Jerome cheaper horses and, I’ll tell you, it’s working,” he said. Fresh off a banner Gulfstream Park TrackMaster President David Siegel to West meet, during which he saddled 11 Retire at Year-End winners from 31 starters, Sweezey so far has four winners with three seconds and Gulfstream Park Charts two thirds during the Championship Meet at Gulfstream that started Dec. 2 Track Results & Entries and continues to March 28, 2021. “We’ve got a good group of horses. J. Kent Sweezey/COADY PHOTO It’s been a learning curve. What we have Florida Stallion Progeny List now are a lot of the lesser-level horses, the COVID thing was going on. -

Investing in Thoroughbreds the Journey

Investing in Thoroughbreds The Journey Owning world-class Thoroughbred race horses is one of the gree credentials, McPeek continually ferrets out not only most exciting endeavors in the world. A fast horse can take people on value but future stars at lower price points. McPeek selected the journey of a lifetime as its career unfolds with the elements of a the yearling Curlin at auction for $57,000, and the colt went great storybook – mystery, drama, adventure, fantasy, romance. on to twice be named Horse of the Year and earn more than $10.5 million. While purchasing horses privately and at major Each race horse is its own individual sports franchise, and the right U.S. auctions, McPeek also has enhanced his credentials by one can venture into worlds once only imagined: the thrilling spotlight finding top runners at sales in Brazil and Argentina. of the Kentucky Derby, Preakness and Belmont Stakes, or to the gathering of champions at the Breeders’ Cup. The right one can lead As a trainer, McPeek has saddled horses in some of the to the historic beauty of Saratoga biggest events in the world, including the Kentucky Derby, Race Course, the horse heaven Breeders’ Cup, Preakness, and Belmont Stakes. Among the called Keeneland or under “Kenny has a unique eye nearly 100 Graded Stakes races that McPeek has won is the the famed twin spires at for Thoroughbred racing talent. He is a 2002 Belmont Stakes with Sarava. More recently in 2020, he Churchill Downs. campaigned the Eclipse Award Winning filly, Swiss Skydiver, superb developer of early racing potential and to triumph in the Preakness. -

I~~Un~~~Re Dm Friday, June 7,1996

The Thoroughbred Daily News is delivered to your home or business by fax each morning by 5a.m. For subscription information, please call 908-747-8060. T~~I~~UN~~~RE DM FRIDAY, JUNE 7,1996 T-R-I-P-L-E THREATS BREEDERS' CUP MOVES SITE OF 1996 Saturday, Belmont Park: BELMONT S.-GI, $734,800, 3yo, 1 112m CHAMPIONSIDP Officials of Breeders' Cup Lim The field of 15, in post position order, will be: ited announced Thursday that the 1996 Breeders' Cup HORSE (Sire) OWNER Championship, scheduled for October 26, will be moved Saratoga Dandy (Saratoga Six) Condren & Cornacchia from Woodbine Racetrack. "We deeply regret this deci Natural Selection (Slew City Slew) Buckram Oak Farm sion to move the Breeders' Cup Championship from South Salem (Salem Drive) Payson & Lucayan Stud Toronto, but without the necessary assurances that the Rocket Flash (Cox's Ridge) Calumet Farm event can be run free of labor disruption, we have no Jamies First Punch (Fit to Fight) Zimpom Stable other alternative," said James E. Bassett III, president of Prince Of Thieves (Hansel) Grimm & Mitchell Breeders' Cup Ltd. "We have no guarantees that ser Editor's Note (Forty Niner) Overbrook Farm vices at the racetrack as well as in the metropolitan Appealing Skier (Baldskil New Farm Toronto area will not be impaired by labor action during My Flag (Easy Goer) Ogden Phipps the time we plan to be in the city, and prudent manage Traffic Circle (Cahill Road) Kimmel/Moelis/Solondz ment dictates that we not expose our Championship and In Contention (Devit's Bag) Noreen Carpenito our visitors to such an environment. -

146Th Running of Triple Crown 146Th Kentucky Derby

146th Running Of Triple Crown 146th Kentucky Derby - 145th Preakness Stakes - 152nd Belmont Stakes $3,000,000 (Grade I) 146TH RUNNING OF THE KENTUCKY DERBY TO BE RUN SATURDAY, MAY 2ND, 2020, 145TH RUNNING OF THE PREAKNESS STAKES TO BE RUN SATURDAY, MAY 16TH, 2020 AND 152ND RUNNING OF THE BELMONT STAKES TO BE RUN SATURDAY JUNE 6TH, 2020 ONE MILE AND ONE-QUARTER TO BE RUN SATURDAY, MAY 2, 2020 *********************************** (17)FASHION STORM ch.c.3 Diamond A Racing Corp. Richard E. Mandella AIRSTREEM gr/ro.c.3 Jackpot Farm and Dede McGehee Steven M. Asmussen AJAAWEED b.c.3 Shadwell Stable Kiaran P. McLaughlin ALL EYES WEST b.c.3 Gary and Mary West Jason Servis ALPHA SIXTY SIX b.c.3 Paul P. Pompa, Jr. Todd A. Pletcher AMEN CORNER b.c.3 Howling Pigeons Farm, LLC Jeremiah O'Dwyer AMERICAN BABY (JPN) dk b/.c.3 Katsumi Yoshizawa Yasushi Shono AMERICAN BUTTERFLY b.c.3 Les Wagner D. Wayne Lukas AMERICAN CODE b.c.3 Byerley Racing, LLC Bob Baffert AMERICAN FACE ch.c.3 Katsumi Yoshizawa Hirofumi Toda AMERICAN SEED b.c.3 Katsumi Yoshizawa Kenichi Fujioka AMERICAN THEOREM gr/ro.r.3 Kretz Racing, LLC George Papaprodromou AMERICANUS b.c.3 Courtlandt Farms Mark A. Hennig ANCIENT LAND dk b/.g.3 Martin Riley, D. Carroll, C. Scott and J. Howard Casey T. Lambert ANCIENT WARRIOR b.c.3 Al Graziani Jerry Hollendorfer ANNEAU D'OR b.c.3 Peter Redekop B. C., Ltd. Blaine D. Wright ANSWER IN b.g.3 Robert V. -

Kentucky Derby Update Saturday, Aug. 29, 2020

Kentucky Derby Update Saturday, Aug. 29, 2020 _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ENFORCEABLE, KING GUILLERMO WORK TOWARD DERBY AT CHURCHILL ENFORCEABLE – Lecomte (GIII) winner Enforceable completed his major Derby preparations by working a half- DOWNS AND TIZ THE LAW DRILLS AT mile in :49.60 under jockey Adam Beschizza. SARATOGA; GAMINE, SWISS SKYDIVER Breezing over a track labeled as good during the 7:30-7:45 TUNE UP FOR OAKS training window for Derby and Oaks runners, Enforceable posted fractions of :12.80, :24.80, :37.20 and galloped out five LOUISVILLE, KY (Saturday, Aug. 29, 2020) – Kentucky furlongs in 1:03.20 while working on his own. Derby hopefuls worked on three fronts Saturday morning “I think he is really improving at this stage of his career,” highlighted by Sackatoga Stable’s Tiz the Law’s five-furlong trainer Mark Casse said. “He’s maturing; he’s ready to go. work in :59.21 over a fast track at Saratoga. “I thought he looked super,” added Casse, who will be Beneath the Twin Spires at Churchill Downs, John seeking the first Kentucky Derby triumph of his Hall of Fame Oxley’s Enforceable worked a half-mile in :49.60 and career. “If you said to me three months ago you could have Victoria’s Ranch’s King Guillermo worked a half-mile in him where he is today and you’d be in the position you’re in, I :52.20. Also working was Peter Callahan’s Swiss Skydiver would have taken it. I just think he’s at the top of his game who covered a half-mile in :49.20 in her final prep for Friday’s right now.