Tragedy Excerpts From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Character of Huckleberry Finn

Forthcoming in Philosophy and Literature 2017 Gehrman The Character of Huckleberry Finn Kristina Gehrman University of Tennessee, Knoxville ABSTRACT: Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn is morally admirable because he follows his heart and does the right thing in a pinch. Or is he? The Character of Huckleberry Finn argues that the standard reading of Huck woefully misunderstands his literary and moral character. The real Huck is strikingly morally passive and thoroughly unreliable, and when the pinch comes, he fails Jim completely. His true character emerges when, with Iris Murdoch’s “justice and love”, we attend to Huck’s youth and his history of unmitigated abuse and neglect. Huck’s case reveals how (and how much) developmental and experiential history matter to moral character. I. Ever since Jonathan Bennett wrote about Huckleberry Finn’s conscience in 1974, Mark Twain’s young hero has played a small but noteworthy role in the moral philosophy and moral psychology literature. Following Bennett, philosophers read Huck as someone who consistently follows his heart and does the right thing in a pinch, firmly believing all the while that what he does is morally wrong.1 Specifically, according to this reading, Huck has racist beliefs that he never consciously questions; but in practice he consistently defies those beliefs to do the right thing in the context of his relationship with his Black companion, Jim. Because of this, Huck is morally admirable, but unusual. Perhaps he is an “inverse akratic,” as Nomy Arpaly and Timothy Schroeder have proposed; or perhaps, as Bennett argued, Huck’s oddness reveals the central and primary role of the sentiments (as opposed to principle) in moral action.2 But the standard philosophical reading of Huckleberry Finn seriously misunderstands his 1 Forthcoming in Philosophy and Literature 2017 Gehrman character (in both the moral/personal and the literary sense of the word), because it does not take into account the historically contingent, developmental nature of persons and their character traits. -

Blake Snyder's Beat Sheet

NYC Screenwriters Collective Blake Snyder’s Beat Sheet - Explained The Blake Snyder Beat Sheet breaks down three-act screenplay structure into 15 bite-size, manageable sections called beats, each with a specific goal for your overall story. Below is an explanation of each beat. The page numbers are not strict, they are approximations of where the beats should occur in a 110 page screenplay. THE BLAKE SNYDER BEAT SHEET (aka BS2) Opening Image (1) – A visual that represents the central struggle & tone of the story. A snapshot of the main character’s problem, before the adventure begins. Often mirrors the Closing Image. Set-up (1-10) – Expand on the opening image. Present the main character’s world as it is, and what is missing in their life. Stasis = Death, the “before” life of the protagonist is such that if it stays the same, he or she will figuratively die. In addition, the main character’s flaw, his problem that needs fixing over the course of the story, is revealed. (In many stories, it is not the main character’s flaw, but another central character’s flaw that is presented for him to resolve over the course of the story – for the character to ‘arc’) Theme Stated (5) (during the Set-up) – The message, the truth you want to reveal by the end of your screenplay. What your story is about in a larger sense. Usually, it is spoken to the main character or in their presence, but they don’t understand this truth…not until they go on the journey to find it. -

Create a Character: Acting & Language Arts with Caren Graham

Create A Character: Acting & Language Arts With Caren Graham ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS LEARNING TARGETS ● How do actors create a character? ● I can make creative choices with my voice and body ● How can characters I discover in other disciplines like to invent a variety of characters history, fairy tales, or literature come to life in ● I can create other forms of dramatic writing or drama? analyze a recording of myself performing MATERIALS NEEDED: Paper and Pencil DIGITAL SUPPORT RESOURCES: <link> INSTRUCTIONS 1. Choose a character from a favorite book. Examples: Harry Potter or Hermione Granger. 2. With pencil and paper write down 3 sentences to describe your chosen character. 3. Use descriptive words like tall, lanky, bent over. 4. Add personality traits like brave, scary, quick witted, confident. 5. Now use your imagination to create a character statue which is a frozen moment in time in a posed position. Start with your face. Try making a “brave” facial expression! a. Is there a moment in Harry Potter, when Harry or Hermione felt clever or brave? Write it down. b. Create that moment in a character statue and then come to life. c. Try to exaggerate (make bigger) a personality trait: for instance brave, and then switch to another feeling or trait like scared. 6. Now add a gesture (an expressive movement) to go with that character trait! a. Move your whole body with expression, posture and gesture. Try saying something in the manner your character might speak with the gesture. b. Acting like the character, did it feel better to be brave or scared? Why? 7. -

The Structure of Plays

n the previous chapters, you explored activities preparing you to inter- I pret and develop a role from a playwright’s script. You used imagina- tion, concentration, observation, sensory recall, and movement to become aware of your personal resources. You used vocal exercises to prepare your voice for creative vocal expression. Improvisation and characterization activities provided opportunities for you to explore simple character portrayal and plot development. All of these activities were preparatory techniques for acting. Now you are ready to bring a character from the written page to the stage. The Structure of Plays LESSON OBJECTIVES ◆ Understand the dramatic structure of a play. 1 ◆ Recognize several types of plays. ◆ Understand how a play is organized. Much of an actor’s time is spent working from materials written by playwrights. You have probably read plays in your language arts classes. Thus, you probably already know that a play is a story written in dia- s a class, play a short logue form to be acted out by actors before a live audience as if it were A game of charades. Use the titles of plays and musicals or real life. the names of famous actors. Other forms of literature, such as short stories and novels, are writ- ten in prose form and are not intended to be acted out. Poetry also dif- fers from plays in that poetry is arranged in lines and verses and is not written to be performed. ■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■■ These students are bringing literature to life in much the same way that Aristotle first described drama over 2,000 years ago. -

Glossary of Literary Terms

Glossary of Critical Terms for Prose Adapted from “LitWeb,” The Norton Introduction to Literature Study Space http://www.wwnorton.com/college/english/litweb10/glossary/C.aspx Action Any event or series of events depicted in a literary work; an event may be verbal as well as physical, so that speaking or telling a story within the story may be an event. Allusion A brief, often implicit and indirect reference within a literary text to something outside the text, whether another text (e.g. the Bible, a myth, another literary work, a painting, or a piece of music) or any imaginary or historical person, place, or thing. Ambiguity When we are involved in interpretation—figuring out what different elements in a story “mean”—we are responding to a work’s ambiguity. This means that the work is open to several simultaneous interpretations. Language, especially when manipulated artistically, can communicate more than one meaning, encouraging our interpretations. Antagonist A character or a nonhuman force that opposes, or is in conflict with, the protagonist. Anticlimax An event or series of events usually at the end of a narrative that contrast with the tension building up before. Antihero A protagonist who is in one way or another the very opposite of a traditional hero. Instead of being courageous and determined, for instance, an antihero might be timid, hypersensitive, and indecisive to the point of paralysis. Antiheroes are especially common in modern literary works. Archetype A character, ritual, symbol, or plot pattern that recurs in the myth and literature of many cultures; examples include the scapegoat or trickster (character type), the rite of passage (ritual), and the quest or descent into the underworld (plot pattern). -

The Effects of Diegetic and Nondiegetic Music on Viewers’ Interpretations of a Film Scene

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Psychology: Faculty Publications and Other Works Faculty Publications 6-2017 The Effects of Diegetic and Nondiegetic Music on Viewers’ Interpretations of a Film Scene Elizabeth M. Wakefield Loyola University Chicago, [email protected] Siu-Lan Tan Kalamazoo College Matthew P. Spackman Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/psychology_facpubs Part of the Musicology Commons, and the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Wakefield, Elizabeth M.; an,T Siu-Lan; and Spackman, Matthew P.. The Effects of Diegetic and Nondiegetic Music on Viewers’ Interpretations of a Film Scene. Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 34, 5: 605-623, 2017. Retrieved from Loyola eCommons, Psychology: Faculty Publications and Other Works, http://dx.doi.org/10.1525/mp.2017.34.5.605 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Psychology: Faculty Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. © The Regents of the University of California 2017 Effects of Diegetic and Nondiegetic Music 605 THE EFFECTS OF DIEGETIC AND NONDIEGETIC MUSIC ON VIEWERS’ INTERPRETATIONS OF A FILM SCENE SIU-LAN TAN supposed or proposed by the film’s fiction’’ (Souriau, Kalamazoo College as cited by Gorbman, 1987, p. 21). Film music is often described with respect to its relation to this fictional MATTHEW P. S PACKMAN universe. Diegetic music is ‘‘produced within the implied Brigham Young University world of the film’’ (Kassabian, 2001, p. -

English Department Handbook 2021-2022

English Department Handbook 2021-2022 EDH 2019-2020 page 2 Table of Contents I. General Policies and Criteria 5 A. Criteria for Composition Grades 5 B. Grading Philosophy 6 C. Graduated Expectations for Evaluating Composition 6 D. Plagiarism 6 E. Quoting, Paraphrasing, and Acknowledging Sources _________________ 6 F. Credible Sources/Computing & Information Technology 7 G. TurnItIn.com 8 H. Policy on Supplementary Sources 9 I. Rationale for Summer Reading 10 J. Philosophy for Text Selection 10 K. Reading is Foundation 11 "A Comment About Censorship" 13 "Teaching Offensive Literature" 13 II. Critical Writing 15 A. Reading the Literature 15 B. Defining Your Audience 16 C. Developing a Good Thesis for Literary Criticism 16 D. Communicating Effectively 18 III. Rules of Form for Formal Assignments 21 A. Title Page Format 22 SAMPLE Title Page 22 B. Page Format 23 C. Outline Page 22 SAMPLE Outlines 24 D. Citation Introduction/Examples 27 SAMPLE Works Cited 29 E. SAMPLE Middle School Essay 31 F. SAMPLE Upper School Essay 34 EDH 2019-2020 page 3 IV. Common Correction Symbols 42 V. Errors Resulting in Major Deductions 43 VI. Glossary of Literary Terms 45 EDH 2019-2020 page 4 I. General Policies and Criteria A. Criteria for Composition Grades A paper earning a grade of A has the following characteristics: 1. Originality in handling a significant topic 2. Logical development of a central idea with thorough supporting evidence 3. Effective organization with strong transitions and unity 4. Variety in sentence structure 5. Appropriate and lively diction 6. No major errors in grammar or expression (Major errors include, but are not limited to, the following: fragment, run-on sentence, comma splice, incorrect subject-verb or pronoun-antecedent agreement, incorrect verb or pronoun usage) A paper earning a grade of B has the following characteristics: 1. -

ELEMENTS of FICTION – NARRATOR / NARRATIVE VOICE Fundamental Literary Terms That Indentify Components of Narratives “Fiction

Dr. Hallett ELEMENTS OF FICTION – NARRATOR / NARRATIVE VOICE Fundamental Literary Terms that Indentify Components of Narratives “Fiction” is defined as any imaginative re-creation of life in prose narrative form. All fiction is a falsehood of sorts because it relates events that never actually happened to people (characters) who never existed, at least not in the manner portrayed in the stories. However, fiction writers aim at creating “legitimate untruths,” since they seek to demonstrate meaningful insights into the human condition. Therefore, fiction is “untrue” in the absolute sense, but true in the universal sense. Critical Thinking – analysis of any work of literature – requires a thorough investigation of the “who, where, when, what, why, etc.” of the work. Narrator / Narrative Voice Guiding Question: Who is telling the story? …What is the … Narrative Point of View is the perspective from which the events in the story are observed and recounted. To determine the point of view, identify who is telling the story, that is, the viewer through whose eyes the readers see the action (the narrator). Consider these aspects: A. Pronoun p-o-v: First (I, We)/Second (You)/Third Person narrator (He, She, It, They] B. Narrator’s degree of Omniscience [Full, Limited, Partial, None]* C. Narrator’s degree of Objectivity [Complete, None, Some (Editorial?), Ironic]* D. Narrator’s “Un/Reliability” * The Third Person (therefore, apparently Objective) Totally Omniscient (fly-on-the-wall) Narrator is the classic narrative point of view through which a disembodied narrative voice (not that of a participant in the events) knows everything (omniscient) recounts the events, introduces the characters, reports dialogue and thoughts, and all details. -

Archetypes Stock Characters (PDF)

STOCK CHARACTERS Shakespeare, as an heir to the Commedia Del-Arte tradition, in which the play’s message is communicated largely through easily recognizable or even stereotypical characters, employs many of “stock” characters throughout his works. Once you look at their basic characteristics, it is easy to identify them across the Shakespearean canon. This identification of characters can make understanding an unfamiliar text a little easier – because the characters in a particular category behave in similar ways, and may even speak using similar rhetorical, image or verse structure. LOVERS ● Ingenue (female): Innocent, sweet, youthful, honorable ● Sobrette (female): Not-so-innocent, not-so-young, usually honorable, witty, likes banter and argument ● Rustic/ Rude (Male and Female): country born and bred, simple, agrarian, earthy. ● Noble (Male): born of nobility, high-born, generally honest COMPANIONS ● Councilors (Male or Female): faithful, honest, convey messages, have information, confidantes. ● Bawds (Female): worldly, saucy, dispense advice, maternal with an edge. ● Mentors (Male): fatherly, give advice, supply the hero with the means to pursue their desire. AUTHORITY FIGURES AND SOLDIERS ● In Control (male): authoritative, most times fair, peripheral to plot, initiate or resolve conflict. ● In Distress (male or female): strong, noble, comprised by circumstance or bad decisions/advice, decisive, often with a flaw of temperament. RELUCTANT HEROES ● Rakes & Cads (male): Walk the line between good and bad but usually turn out good,witty, bawdy, seductive, hot-tempered, loyal but independent. COMIC CHARACTERS ● The Wit: Language based humor, somewhat noble, melancholy. ● The Clown: Physical comic, jester, paid to be amusing, singer. ● The Fool: situational comic, dim-witted, unaware of being a fool. -

Hesitancy As an Innate Flaw in Hamlet's Character: Reading Through a Psychoanalytic Lens

Vol.11(2), pp. 21-28, April-June 2020 DOI: 10.5897/IJEL2020.1330 Article Number: C39C39A63540 ISSN 2141-2626 Copyright © 2020 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article International Journal of English and Literature http://www.academicjournals.org/IJEL Review Hesitancy as an innate flaw in Hamlet's character: Reading through a psychoanalytic lens Abdul Mahmoud Idrees Ibrahim Department of English Language, Thadiq College, Shaqra University, Saudi Arabia. Received 29 January, 2020; Accepted 18 March, 2020 This paper concentrated on hesitancy as a character's flaw from the Freudian psychoanalysis focal point. Hamlet's uncertainty is especially identified with his natural complex which frames his oblivious love for his mom and his lethal abhor for his dad. Freud's ideas of man's concealed want for annihilation and eradication may shape the reason for understanding Hamlet's craving for death and suicide as demonstrated by his popular monologs. Ridiculousness and agnosticism in Hamlet's activities mirror the intrinsic human conduct and flaw. The paper suggests that Hamlet's play ought to be remembered for cutting edge writing courses for its lavishness in examples of general human conduct, for example, the recurrence that is natural to human activities on different events. Educators should expand under study's attention to the nearness of hesitancy and uncertainty as a flaw that can prompt pulverization as Hamlet does. Key words: Character, critics, flaw, Freudian psychoanalysis, Hamlet play, hesitancy, tragedy. INTRODUCTION Hamlet is one of the most astounding and awesome bolsters the idea of the flaw of Hamlet's character and the plays. -

Orson Scott Card's <I>Ender's Game</I>

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Department of English, Literature, and Modern English Seminar Capstone Research Papers Languages 4-15-2013 The eH roic Fallacy: Orson Scott aC rd’s Ender’s Game and the Young Adult Reader Shawn L. Buice Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ english_seminar_capstone Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Buice, Shawn L., "The eH roic Fallacy: Orson Scott aC rd’s Ender’s Game and the Young Adult Reader" (2013). English Seminar Capstone Research Papers. 17. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/english_seminar_capstone/17 This Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Seminar Capstone Research Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Shawn Buice Dr. Deardorff Senior Seminar 15 April 2013 The Heroic Fallacy: Orson Scott Card’s Ender’s Game and the Young Adult Reader Buice 1 This paper was an opportunity to connect my education as a student of literature with my past experience as a reader. I was always more comfortable reading young adult, science fiction or fantasy novels, perhaps because this is what I read growing up. Interestingly, a trend of the past decade in British literary criticism has been to study crossover literature. This includes books that have been widely read by both adults and children. The case for studying adolescent fiction intersects with studies of crossover fiction. Individuals for whom reading was a formative part of their upbringing, by taking a closer look at adolescent fiction can peer into the past and try to understand the events and experiences that shaped the yet unmolded identity. -

Documentation Title

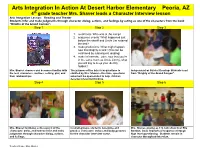

Arts Integration In Action At Desert Harbor Elementary Peoria, AZ th 4 grade teacher Mrs. Shaver leads a Character Interview lesson Arts Integration Lesson: Reading and Theater Students infer and make judgments through character dialog, actions, and feelings by acting as one of the characters from the book “Brighty of the Grand Canyon”. Step 1 Step 2 Step 3 1. recall facts: Who was at the camp? 2. sequence events: What happened just before the sheriff and Uncle Jim entered the tent? 3. make predictions: What might happen now that Brighty is sick? (this can be confirmed by subsequent reading) 4. make inferences: Jake, now that you’re in the same room as Uncle Jimmy, what you will say to keep your identity hidden? Mrs. Shaver chooses and becomes familiar with The purpose of the interview questions is Independent or Guided Reading- Students read the text, characters, motives, setting, plot, and clarified by Mrs. Shaver—this time, questions from “Brighty of the Grand Canyon”. their relationships. asked will be open-ended to help children develop inferential thinking. Step 4 Step 5 Step 6 Mrs. Shaver facilitates a discussion of the In small groups, students determine and Mrs. Shaver, posing as T.V. talk show host Ella characters’ traits, and how we infer and make practice characters’ voices and body gestures Stration, leads improvised responses through judgments through character dialog, actions, for the character interview scene. high level questioning. Students remain in and feelings. character throughout interview. Teacher Name: Mrs. Shaver Learning Objectives Student Reflections Language Arts - Reading Concept 6 Comprehension: Employ strategies to comprehend text.