On View: New Work: Nancy Chunn, Michael Corris, Olivier Mosset

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dissertatie Cvanwinkel

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) During the exhibition the gallery will be closed: contemporary art and the paradoxes of conceptualism van Winkel, C.H. Publication date 2012 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): van Winkel, C. H. (2012). During the exhibition the gallery will be closed: contemporary art and the paradoxes of conceptualism. Valiz uitgeverij. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:03 Oct 2021 7 Introduction: During the Exhibition the Gallery Will Be Closed • 1. RESEARCH PARAMETERS This thesis aims to be an original contribution to the critical evaluation of conceptual art (1965-75). It addresses the following questions: What -

SOLO and TWO-PERSON EXHIBITIONS 2007 the Stone Age, CANADA, New York, NY Project: Rendition, Momenta Art, Brooklyn, NY

CARRIE MOYER [email protected] SOLO AND TWO-PERSON EXHIBITIONS 2007 The Stone Age, CANADA, New York, NY Project: Rendition, Momenta Art, Brooklyn, NY. Collaboration by JC2: Joy Episalla, Joy Garnett, Carrie Moyer, and Carrie Yamaoka Black Gold, rowlandcontemporary, Chicago, IL Black Gold, Hunt Gallery, Mary Baldwin College, Staunton, VA 2006 Carrie Moyer and Diana Puntar, Samson Projects, Boston, MA 2004 Two Women: Carrie Moyer and Sheila Pepe, Palm Beach ICA, Palm Beach, FL (catalog) Sister Resister, Diverseworks, Houston, TX Façade Project, Triple Candie, New York, NY 2003 Chromafesto, CANADA, New York, NY 2002 Hail Comrade!, Debs & Co., New York, NY The Bard Paintings, Gallery @ Green Street, Boston, MA Meat Cloud, Debs & Co., New York, NY Straight to Hell: 10 Years of Dyke Action Machine! Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco, CA; Diverseworks, Houston, TX (traveling exhibition with catalog) 2000 God’s Army, Debs & Co., New York, NY GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2007 Don’t Let the Boys Win: Kinke Kooi, Carrie Moyer, and Lara Schnitger, Mills College Art Museum, Oakland, CA Late Liberties, John Connelly Presents, New York, NY. Curator: Augusto Abrizo Shared Women, Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions (LACE), Los Angeles, CA. Curators: Eve Fowler, Emily Roysdon, A.L. Steiner Beauty Is In the Streets, Mason Gross School of the Arts Galleries, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ Affinities: Painting in Abstraction, CCS Galleries, Hessel Museum, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, NY. Curator: Kate McNamara Absolute Abstraction, Judy Ann Goldman Fine Arts, Boston, MA Hot and Cold: Abstract Prints from the Center Street Studio, Trustman Art Gallery, Simmons College, Boston, MA New Prints/Spring 2007, IPCNY/International Print Center New York, New York, NY. -

Cartographic Perspectives Information Society 1

Number 53, Winterjournal 2006 of the Northcartographic American Cartographic perspectives Information Society 1 cartographic perspectives Number 53, Winter 2006 in this issue Letter from the Editor INTRODUCTION Art and Mapping: An Introduction 4 Denis Cosgrove Dear Members of NACIS, FEATURED ARTICLES Welcome to CP53, the first issue of Map Art 5 Cartographic Perspectives in 2006. I Denis Wood plan to be brief with my column as there is plenty to read on the fol- Interpreting Map Art with a Perspective Learned from 15 lowing pages. This is an important J.M. Blaut issue on Art and Cartography that Dalia Varanka was spearheaded about a year ago by Denis Wood and John Krygier. Art-Machines, Body-Ovens and Map-Recipes: Entries for a 24 It’s importance lies in the fact that Psychogeographic Dictionary nothing like this has ever been kanarinka published in an academic journal. Ever. To punctuate it’s importance, Jake Barton’s Performance Maps: An Essay 41 let me share a view of one of the John Krygier reviewers of this volume: CARTOGRAPHIC TECHNIQUES …publish these articles. Nothing Cartographic Design on Maine’s Appalachian Trail 51 more, nothing less. Publish them. Michael Hermann and Eugene Carpentier III They are exciting. They are interest- ing: they stimulate thought! …They CARTOGRAPHIC COLLECTIONS are the first essays I’ve read (other Illinois Historical Aerial Photography Digital Archive Keeps 56 than exhibition catalogs) that actu- Growing ally try — and succeed — to come to Arlyn Booth and Tom Huber terms with the intersections of maps and art, that replace the old formula REVIEWS of maps in/as art, art in/as maps by Historical Atlas of Central America 58 Reviewed by Mary L. -

Michael Scott

BIOGRAPHY & BIBLIOGRAPHY michael scott Born in 1958 in Paoli, Pennsylvania. Lives and works in New York. Solo shows: 2018 Circle Paintings, Xippas, Paris, France Galerie Xippas, Geneva, Switzerland 2017 Recent Painting and sculpture, Sandra Gering Gallery, New York, USA 2015 Michael Scott, Laurent Strouk, Paris, France Courants alternatifs, Triple V Gallery, Paris, France 2014 Michael Scott and John Chamberlain: a conversation, Sandra Gering, New York, USA Michael Scott, Xippas Art Contemporain, Geneva, Switzerland Michael Scott - To Present, Circuit, Centre d’Art contemporain, Lausanne, Switzerland 2013 Black and White Paintings, Triple V, Paris, France 2012 Black & Blue, Galerie Odermatt-Vedovi, Brussels, Belgium Michael Scott: Buffalo Bulb’s Wild West Show, The Art Museum of South Texas, USA Michael Scott: Black and White Line Paintings 1989 - 2011, Gering & López Gallery, New York City, USA 2011 Michael Scott, Gering & López, New York, Witzenhausen Gallery, Amsterdam, Netherlands 2010 Recent Paintings, Triple V, Paris, France The Inner Eye, Witzenhausen gallery, New York, USA (with Roland Schimmel) 2009 And Then He Tried To Swallow The World, Gering & Lopez, New York, USA 2008 New Works, Triple V, Dijon, France 2002 Central Connecticut State University (avec Toby Kilpatrick), New Britain 1999 Sandra Gering Gallery, New York, USA 1998 Art & Public (avec Steven Parrino), Geneva, Switzerland 1997 Atheneum, Université de Dijon, Dijon, France 1996 Sandra Gering Gallery, New York, USA 1995 Art & Public, Geneva, Switzerland 1994 Tony Shafrazi Gallery, New York*, USA 1993 Akira Ikeda Gallery, Nagoya (Japon) Jason Rubell Gallery, Miami, USA 1991 Le Consortium (avec Steve DiBenedetto), Dijon, France 1990 Tony Shafrazi Gallery, New York, USA Brent Sikkema Gallery, New York, USA 1989 Tony Shafrazi Gallery, New York, USA 1987 Mission West, New York, USA J. -

The Dialogical Imagination: the Conversational Aesthetic of Conceptual Art

THE DIALOGICAL IMAGINATION: THE CONVERSATIONAL AESTHETIC OF CONCEPTUAL ART MICHAEL CORRIS Within the history of avant-garde art there is a recurrent interest in process-based practices. A substantial claim made by proponents of this position argues that process-based practices offer far more scope for the revision of the conventional culture of art than any other type of practice. In the first place, process-based practices dispense with the idea of the production of a material object as the principle aim of art. While there is often a material ‘residue’ associated with process- based art, its status as an autonomous object of art is always questionable. Such objects are more properly understood as props or by-products, and are valued accordingly by the artist (but not, alas, by the critic, curator or collector). Process-based practices themselves raise difficult questions for connoisseurs; there is often no clear notion where to locate the boundary dividing process works from the environment at large. The process-based work of art may not result in an object at all; rather, it could be a performance (scripted or not), an environment or installation, an intervention in a public space, or some sort of social encounter, such as a conversation or an on-going project with a community. The point of all these practices is to radically alter the subject-position of both artist and beholder. By so doing, the very idea of the autonomy of art is placed in question. Once attention and purpose are shifted from the making of what amounts to medium- sized dry goods, so the argument goes, both artist and spectator are liberated. -

Conceptual Art: a Critical Anthology

Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology Alexander Alberro Blake Stimson, Editors The MIT Press conceptual art conceptual art: a critical anthology edited by alexander alberro and blake stimson the MIT press • cambridge, massachusetts • london, england ᭧1999 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval)without permission in writing from the publisher. This book was set in Adobe Garamond and Trade Gothic by Graphic Composition, Inc. and was printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Conceptual art : a critical anthology / edited by Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-262-01173-5 (hc : alk. paper) 1. Conceptual art. I. Alberro, Alexander. II. Stimson, Blake. N6494.C63C597 1999 700—dc21 98-52388 CIP contents ILLUSTRATIONS xii PREFACE xiv Alexander Alberro, Reconsidering Conceptual Art, 1966–1977 xvi Blake Stimson, The Promise of Conceptual Art xxxviii I 1966–1967 Eduardo Costa, Rau´ l Escari, Roberto Jacoby, A Media Art (Manifesto) 2 Christine Kozlov, Compositions for Audio Structures 6 He´lio Oiticica, Position and Program 8 Sol LeWitt, Paragraphs on Conceptual Art 12 Sigmund Bode, Excerpt from Placement as Language (1928) 18 Mel Bochner, The Serial Attitude 22 Daniel Buren, Olivier Mosset, Michel Parmentier, Niele Toroni, Statement 28 Michel Claura, Buren, Mosset, Toroni or Anybody 30 Michael Baldwin, Remarks on Air-Conditioning: An Extravaganza of Blandness 32 Adrian Piper, A Defense of the “Conceptual” Process in Art 36 He´lio Oiticica, General Scheme of the New Objectivity 40 II 1968 Lucy R. -

November Newsletter

This Month in the Arts ART, ART HISTORY, TECHNOCULTURAL STUDIES, AND THE RICHARD L. NELSON GALLERY AND FINE ART COLLECTION NOVEMBER 2008 EVENTS Michael Corris, “The Dialogical Imagination: Art After the Beholder's Share from Abstract Expressionism to the Conversational Aesthetic of Conceptual Art” Friday In place of an art object whose media identity was secure and of 11/7/2008 sufficient external complexity and detail, Conceptual Art substi- 4:00 PM tuted text, ephemeral performances, banal photography and in- Art 210 stallations virtually indistinguishable from the environment in which they were sited. This paper will consider those practices of Con- ceptual Art that sought to dispense with the spectator entirely through artistic strategies that foreground the act of conversation, interactivity and a radical application of intellectual re- sources associated with the task of indexing and information retrieval. Under such conditions of engagement, can one sensible speak of a work of art at all? If so, what might the 'work' be that a work of art of this sort aims to do? Michael Corris is Professor of Fine Art at the Art and Design Research Center, Sheffield Hal- lam University, Sheffield; the Newport School of Art, Media and Design; and a visiting Profes- sor in Art Theory at the Art Academy, Bergen. A former member of the Conceptual art group Art & Language, Corris’s papers and archive of early Conceptual art are now housed at the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles. His art criticism has been widely published in journals and magazines devoted to modern and contemporary art including Art Monthly, Artforum, FlashArt, Art History, art+text and Mute. -

Leonardo Electronic Almanac VOLUME 9, NO

/ ____ / / /\ / /-- /__\ /______/____ / \ ============================================================= Leonardo Electronic Almanac VOLUME 9, NO. 2 2001 Roger Malina, LEA Executive Editor Michael Punt, LDR Editor-in-Chief Craig Harris, LEA Guest Editor Patrick Lambelet, LEA Managing Editor Editorial Advisory Board: Roy Ascott, Michael Naimark, Simon Penny, Greg Garvey, Joan Truckenbrod ISSN #1071-4391 ============================================================= ____________ | | | CONTENTS | |____________| ============================================================= INTRODUCTION < Leonardo Lawsuit Update > < Leonardo Auction > LEONARDO JOURNAL < Abstracts of Articles Forthcoming in Leonardo: Vol. 34, No. 2 (April 2001) > < Table of Contents for Leonardo Vol. 34, No. 3 (June 2001) > LEONARDO DIGITAL REVIEWS < This Month’s Reviews > Michael Punt < From Handel to Hendrix: The Composer in the Public Sphere > by Michael Chanan. Reviewed by Sean Cubitt. LEONARDO MUSIC JOURNAL < Ten Years of Leonardo Music Journal > Nicolas Collins < LMJ 10-Year Anniversary Event > ISAST NEWS < FluidArts: Leonardo/OLATS collaborate in new art and education venture > < Virtual Africa: The Spirit and Power of Water > ENDNOTE < The Genome and Art: Finding Potential in Unlikely Places > Ellen K. Levy 1 LEONARDOELECTRONICALMANAC VOL 9 NO 2 ISSN 1071-4391 ISBN 978-0-9833571-0-0 ANNOUNCEMENTS < Tout-Fait: The Marcel Duchamp Studies Online Journal > ===================================================================== ________________ | | | INTRODUCTION | |________________| -

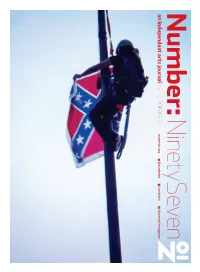

Number 97 Color Resized 11X15.Indd

Number: NinetySeven an independent arts journal/spring 2019/relics numberinc.org @numberinc numberinc @numberincmagazine Editorial 97: Relics Screen Shot of James 03 Christine Bespalec-Davis Tyson’s Coverage of Support those who Bree Newsome, Charlotte, support the Arts: Regional Updates: Cover: NC, June 27, 2015 Listings for Artists, Galleries, Organizations, Editorial 97: Relics Memphis / Tennessee 04 Northwest Arkansas / Atlanta and Businesses that Make Art Happen Objects and images, preserved in archives, or im- all over again. I still have those things and a few other the vanishing point of a rainy street in Paris and the Pulse material and memorialized in the annals of memory: cherished items she had set aside for me. They are velvet blackness of a man’s umbrella in contrast to a 06 Gloria Ballard Memphis, TN Nashville, TN these are Relics. They are evocative, even provocative, heirlooms that will go to my children when I am gone. woman’s red lips. I would sneak away from my parents Art Center Building No.9 1636 Union Avenue 57 Arcade and, through miraculous belief, these cultural traces After my grandmother died, though, what I re- to stand too close to Picasso, positioning myself so One Can Indeed Not Account Memphis, TN 38104 Nashville, TN 901.276.6321 615.983.0400 and markers of personal identity persevere. They member actually wanting was something completely there was just enough glare to see the eye and jawline Bailey Romaine artcentermemphis.com Contact: Peter Fleming 07 [email protected] channel people, places, events, and ideas from the re- different: a piece of wallpaper in her only bathroom. -

Download the PDF Here

PRESS RELEASE NB: PARTICULARS RELATED TO THE INFORMATION NOT CONTAINED HEREIN CONSTITUTE THE FORM OF THIS ACTION1 &/OR REGARDING SUPPORT LANGUAGES AND THE POSSIBILITY OF SELF VALIDATION NB RETURN OF THE LIVING DEAD III. INCLUDING: CLEMENT GREENBERG IS A CONCEPTUAL ARTIST and FLATNESS AND SHAPE-ISM.2 ‘Aaaah… yeah well we’re all full of shit!’ Greenberg on Jackson Pollock. T.J. Clark interviews Clement Greenberg. Open University TV progamme (1994) 1. Introduction: Night of the Living Dead. The intentionality prerequisite to this text is to use Clement Greenberg’s description of flatness as an AQUA-SHAPE-MODEL-CRYSTAL to think through the relationship between art criticism and the artwork. Or more (or less) specifically the question: what do words do to (art) objects? In a contemporary sense, this might relate to the recently characterised ‘crisis in criticism,’ for example, see October (Spring 2002), Frieze (August 2006) and ArtDeath (January 2007). Or in broader art-historico- philosophical environs to the distinctions drawn between the visual and the linguistic, words and things, form and content – as Foucault puts it: ‘…the oldest oppositions of our alphabetic civilization: to show and to name; to shape and to say; to reproduce and to articulate; to imitate and to signify; to 1. Telegram cable (as artwork) sent by the artist Christine Kozlov to Kynaston McShine, curator of Information (1970). The negation of representational information as its own source of representation. 2. Robert Garnett suggested the term Shapeism via Tony Hancock and Giles Deleuze. look and to read.’3 The intention here is not to re-re-re-reanimate the Living Dead form/content debate and/or contemporary corpses of the aesthetico-beauty and/or critico-antagonism debacle-argument. -

Naturally Hypernatural

ANTENNAE ISSUE 34 – WINTER 2015 ISSN 1756-9575 Naturally Hypernatural Suzanne Anker – Petri[e]’s Panopolis / Laura Ballantyne-Brodie – Earth System Ethics / Janet Gibbs – A Step on the Sun / Henry Sanchez – The English Kills Project / Steve Miller and Adam Stennett – Artist Survival Shack / Joe Mangrum – Sand Paintings / Tarah Rhoda and Nancy Chunn – Chicken Little and the Culture of Fear / Sarah E Durand – Newtown Creek ANTENNAE The Journal of Nature in Visual Culture Editor in Chief Giovanni Aloi – School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Sotheby’s Institute of Art London and New York, Tate Galleries Academic Board Advisory Board Steve Baker – University of Central Lancashire Rod Bennison Ron Broglio – Arizona State University Helen J. Bullard Matthew Brower – University of Toronto Claude d’Anthenaise Eric Brown – University of Maine at Farmington Lisa Brown Carol Gigliotti – Emily Carr University of Art and Design in Vancouver Chris Hunter Donna Haraway – University of California, Santa Cruz Karen Knorr Susan McHugh – University of New England Susan Nance Brett Mizelle – California State University Andrea Roe Claire Molloy – Edge Hill University David Rothenberg Cecilia Novero – University of Otago Angela Singer Jennifer Parker-Starbuck – Roehampton University Mark Wilson & Bryndís Snaebjornsdottir Annie Potts – University of Canterbury Ken Rinaldo – Ohio State University Nigel Rothfels – University of Wisconsin Jessica Ullrich – Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg Andrew Yang – School of the Art Institute of Chicago Global Contributors Antennae (founded in 2006) is the international, peer reviewed, academic Sonja Britz journal on the subject of nature in contemporary art. Its format and Tim Chamberlain contents are inspired by the concepts of 'knowledge transfer' and 'widening Conception Cortes participation'. -

A&L PR English

ART & LANGUAGE ‘HOMELESS STUFF’ 7 JUNE – 15 JULY 2017 Rob Tufnell presents a retrospective of posters, prints, postcards, journals, jigsaws, records, video and ephemera produced by Art & Language between 1969 and 2017. In 1968 ‘Art & Language’ was adopted as the nom de guerre a group of artists teaching at Coventry College of Art. The initial group of Terry Atkinson, David Bainbridge, Michael Baldwin and Harold Hurrell had a shared interest in producing what is now understood as Conceptual Art (a movement Mel Ramsden has since characterised as ‘Modernism’s nervous breakdown’). Their practice, was informed by broad interests including philosophies of science, mathematics and linguistics. They embraced Paul Feyerabend’s notion of “epistemological anarchy” to find new ways of producing, presenting and understanding art. They sought to replace Modernism’s ambitions of certainty and refinement with confusion and contradiction or a state of ‘Pandemonium’ (from John Milton’s ‘Paradise Lost’ (1667)). In 1969 they published the first of 22 issues of the journal ‘Art-Language’ with texts by Terry Atkinson, David Bainbridge and Michael Baldwin and others alongside contributions from Dan Graham, Sol Le Witt and Lawrence Weiner. After they were joined in 1970 by Ian Burn and Mel Ramsden the group quickly expanded forming around two nuclei in the small town of Chipping Norton in Oxfordshire, England and in New York. In the following years they were joined by Charles and Sandra Harrison, Graham Howard, Lynn Lemaster, Philip Pilkington, David Rushton and Paul Wood (in England) and Kathryn Bigelow, Michael Corris, Preston Heller, Christine Kozlov and Andrew Menard (in New York).