Total of 10 Pages Only May Be Xeroxed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

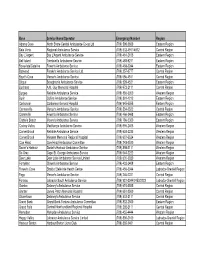

Revised Emergency Contact #S for Road Ambulance Operators

Base Service Name/Operator Emergency Number Region Adams Cove North Shore Central Ambulance Co-op Ltd (709) 598-2600 Eastern Region Baie Verte Regional Ambulance Service (709) 532-4911/4912 Central Region Bay L'Argent Bay L'Argent Ambulance Service (709) 461-2105 Eastern Region Bell Island Tremblett's Ambulance Service (709) 488-9211 Eastern Region Bonavista/Catalina Fewer's Ambulance Service (709) 468-2244 Eastern Region Botwood Freake's Ambulance Service Ltd. (709) 257-3777 Central Region Boyd's Cove Mercer's Ambulance Service (709) 656-4511 Central Region Brigus Broughton's Ambulance Service (709) 528-4521 Eastern Region Buchans A.M. Guy Memorial Hospital (709) 672-2111 Central Region Burgeo Reliable Ambulance Service (709) 886-3350 Western Region Burin Collins Ambulance Service (709) 891-1212 Eastern Region Carbonear Carbonear General Hospital (709) 945-5555 Eastern Region Carmanville Mercer's Ambulance Service (709) 534-2522 Central Region Clarenville Fewer's Ambulance Service (709) 466-3468 Eastern Region Clarke's Beach Moore's Ambulance Service (709) 786-5300 Eastern Region Codroy Valley MacKenzie Ambulance Service (709) 695-2405 Western Region Corner Brook Reliable Ambulance Service (709) 634-2235 Western Region Corner Brook Western Memorial Regional Hospital (709) 637-5524 Western Region Cow Head Cow Head Ambulance Committee (709) 243-2520 Western Region Daniel's Harbour Daniel's Harbour Ambulance Service (709) 898-2111 Western Region De Grau Cape St. George Ambulance Service (709) 644-2222 Western Region Deer Lake Deer Lake Ambulance -

• Articles • Becoming Local

PAGE 44 • Articles • Becoming Local: The Emerging Craft Beer Industry in Newfoundland, Canada NATALIE DIGNAM Memorial University of Newfoundland Abstract: This article considers the ways craft breweries integrate the local culture of Newfoundland, Canada in their branding, events and even flavors. Between 2016 and 2019, the number of craft breweries in Newfoundland quadrupled. This essay examines how this emerging industry frames craft beer as local through heritage branding that draws on local customs and the island's unique language. At the same time, some breweries embrace their newness by reinterpreting representations of rural Newfoundland. In May of 2017, I moved from Massachusetts to the island of Newfoundland with my husband. "The Rock," as it's nicknamed, part of Canada's easternmost province of Newfoundland and Labrador, is an isolated island of over 155,000 square miles of boreal forest, bluffs and barrens. During that first summer, we were enthralled by the East Coast Trail, a hiking trail that loops around the Avalon Peninsula on the eastern edge of the island. From rocky cliffs, we spotted whales, hawks, icebergs, and seals. We often ate a "feed of fish and chips," as I have heard this popular dish called in Newfoundland. One thing we missed from home were the numerous craft breweries, where we could grab a pint after a day of hiking. We had become accustomed to small, locally-owned breweries throughout New England, operating out of innocuous locations like industrial parks or converted warehouses, where we could try different beers every time we visited. I was disappointed to find a much more limited selection of beer when I moved to Newfoundland. -

The Newfoundland and Labrador Gazette

THE NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR GAZETTE PART I PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY Vol. 91 ST. JOHN’S, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 28, 2016 No. 43 GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES BOARD ACT NOTICE UNDER THE AUTHORITY of subsection 6(1), of the Geographical Names Board Act, RSNL1990 cG-3, the Minister of the Department of Municipal Affairs, hereby approves the names of places or geographical features as recommended by the NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES BOARD and as printed in Decision List 2016-01. DATED at St. John's this 19th day of October, 2016. EDDIE JOYCE, MHA Humber – Bay of Islands Minister of Municipal Affairs 337 THE NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR GAZETTE October 28, 2016 Oct 28 338 THE NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR GAZETTE October 28, 2016 MINERAL ACT DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES JUSTIN LAKE NOTICE Manager - Mineral Rights Published in accordance with section 62 of CNLR 1143/96 File #'s 774:3973; under the Mineral Act, RSNL1990 cM-12, as amended. 775:1355, 3325, 3534, 3614, 5056, 5110 Mineral rights to the following mineral licenses have Oct 28 reverted to the Crown: URBAN AND RURAL PLANNING ACT, 2000 Mineral License 011182M Held by Maritime Resources Corp. NOTICE OF REGISTRATION Situate near Indian Pond, Central NL TOWN OF CARBONEAR On map sheet 12H/08 DEVELOPMENT REGULATION AMENDMENT NO. 33, 2016 Mineral License 017948M Held by Kami General Partner Limited TAKE NOTICE that the TOWN OF CARBONEAR Situate near Miles Lake Development Regulations Amendment No. 33, 2016, On map sheet 23B/15 adopted on the 20th day of July, 2016, has been registered by the Minister of Municipal Affairs. -

(PL-557) for NPA 879 to Overlay NPA

Number: PL- 557 Date: 20 January 2021 From: Canadian Numbering Administrator (CNA) Subject: NPA 879 to Overlay NPA 709 (Newfoundland & Labrador, Canada) Related Previous Planning Letters: PL-503, PL-514, PL-521 _____________________________________________________________________ This Planning Letter supersedes all previous Planning Letters related to NPA Relief Planning for NPA 709 (Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada). In Telecom Decision CRTC 2021-13, dated 18 January 2021, Indefinite deferral of relief for area code 709 in Newfoundland and Labrador, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) approved an NPA 709 Relief Planning Committee’s report which recommended the indefinite deferral of implementation of overlay area code 879 to provide relief to area code 709 until it re-enters the relief planning window. Accordingly, the relief date of 20 May 2022, which was identified in Planning Letter 521, has been postponed indefinitely. The relief method (Distributed Overlay) and new area code 879 will be implemented when relief is required. Background Information: In Telecom Decision CRTC 2017-35, dated 2 February 2017, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) directed that relief for Newfoundland and Labrador area code 709 be provided through a Distributed Overlay using new area code 879. The new area code 879 has been assigned by the North American Numbering Plan Administrator (NANPA) and will be implemented as a Distributed Overlay over the geographic area of the province of Newfoundland and Labrador currently served by the 709 area code. The area code 709 consists of 211 Exchange Areas serving the province of Newfoundland and Labrador which includes the major communities of Corner Brook, Gander, Grand Falls, Happy Valley – Goose Bay, Labrador City – Wabush, Marystown and St. -

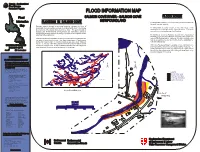

Flood Information Map

Canada - Newfoundland Flood Damage Reduction Program FLOOD INFORMATION MAP Flood SALMON COVE RIVER - SALMON COVE FLOOD ZONES NEWFOUNDLAND Information FLOODING IN SALMON COVE A "designated floodway" (1:20 flood zone) is the area subject to the most frequent flooding. Map Flooding causes damage to personal property, disrupts the lives of individuals and communities, and can be a threat to life itself. Continuing A "designated floodway fringe" (1:100 year flood zone) development of flood plain increases these risks. The governments of constitutes the remainder of the flood risk area. This area Canada and Newfoundland and Labrador are sometimes asked to generally receives less damage from flooding. compensate property owners for damage by floods or are expected to find solutions to these problems. No building or structure should be erected in the "designated floodway" since extensive damage may result from deeper and Past flood events at have been caused by a combination of high flows and more swiftly flowing waters. However, it is often desirable, and ice jams at hydraulic structures. The area downstream of the highway may be acceptable, to use land in this area for agricultural or bridge has been subject to flooding nearly every year when break-up recreational purposes. occurs. In January 1995 heavy rainfall combined with snowmelt to cause SALMON COVE RIVER flooding in Salmon Cove. In the RIverdale Crescent area the bridge was Within the "floodway fringe" a building, or an alteration to an overtopped and flooding properties adjacent to the bridge. existing building, should receive flood proofing measures. A SALMON COVE variety of these may be used, eg. -

Regional News

REGIONAL FIS E IES NEWS J liaRY 1970 ( 1 • Mdeit,k40 111.111111111...leit 9 DEPARTMENT OF FISHERIES OF CANADA NEWFOUNDLAND REGION REDUCTION PLANT OFFICIALLY OPENED The ne3 3/4-million NATLAKE herring reduction plant at Burgeo was officially opened January 28th by Premier J. R. Smallwood. Among special guests attending the opening ceremonies were: federal Transport Minister Don Jamieson, provincial Minister of Fisheries A. Maloney and our Regional Director, H. R. Bradley. Privately financed, the new plant is a joint effort of Spencer Lake, the Clyde Lake Group and National Sea Products of Nova Scotia. Ten herring seiners from Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and British Columbia are under contract to land catches at the plant. Fifty people will be employed as production workers at the plant which will operate on a 21-hour, three shift basis. - 0 - 0 - 0 - ATTEND CAMFI CONFERENCE Four representatives of Regional Headquarters staff are attending the Conference on Automation and Mechanization in the Fishing Industry being held in Montreal February 3 - 6. The conference is sponsored by the Federal-Provincial Atlantic Fisheries Committee which is comprised of the deputy ministers responsible for fisheries in the Federal Government and the governments of Quebec, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland. The Secretariat for the conference was provided by the Industrial Development Service, Department of Fisheries and Forestry, Ottawa. Attending the conference from the Newfoundland. Region were: J. P. Hennessey, R. n. Prince, m. Barnes and E. B. Dunne. ****** ****** FROZEN TROUT RETURN TO LIFE A true story told by Bob Ebsary, a former technician with our Inspection Laboratory, makes one wonder whether or not trout, like cats, have nine lives. -

The Catskill Canister Volume 52 Number 2 April - June 2019

The Catskill Canister Volume 52 Number 2 April - June 2019 View from Twin. Photo by Jason Pelton, #3013 W1211 In this issue: President's Column Trail Mix: News and Notes from the Club Winter Weekend recap A Road Less Traveled... The Catskill 200 Camping with Children Did you know? The Catskill Adventure Patch Catskill Park Day 2019 A year spent climbing Remembering Father Ray Donahue Wildflowers - readers' favorite spots Fond memories of the Otis Elevator Race Nettles - A forager's delight Conservation Corner Annual Dinner announcement Hike Schedule Member lists Editor's Notes 1 Spathe and Spadix The President’s Column by Heather Rolland When the Catskill 3500 Club was created, our mission – to promote hiking the high peaks of the Catskills, to promote social interaction among Catskill high peak hikers, and to support conservation of these places – filled a void. In a world with no internet and thus no social media, helping hikers connect with each other was a valued and needed service. Because if there’s one thing I’ve learned in my decade or so of involvement with this club, it’s that the only thing hikers enjoy more than hiking is talking about hiking! Sharing war stories, trading bushwhack routes, and waxing euphoric about views… hikers, it would seem to me, love the replay with the like-minded as much as they love the adventure itself. But things have changed, and now that camaraderie is available in spades via social media. Leave No Trace is a national not-for-profit environmental organization on the frontlines of dealing with the good, the bad, and the ugly of managing the immense current upsurge in popularity of hiking and outdoor recreation. -

A Brief History of the Random Region of Trinity Bay

A Brief History of the Random Region of Trinity Bay A Presentation to the Wessex Society St. John's, Nfld. Leslie J. Dean April, 1994 Revised June 16, 1997 HISTORY OF THE RANDOM REGION OF TRINITY BAY INTRODUCTION The region encompassed by the Northwest side of Trinity Bay bounded by Southwest Arm (of Random), Northwest Arm (of Random), Smith's Sound and Random Island has, over the years, been generally referred to as "Random". However, "Random" is now generally interpreted locally as that portion of the region encompassing Southwest Arm and Northwest Arm. Effective settlement of the region as a whole occurred largely during the 1857 - 1884 period. A number of settlements at the outer fringes of the region including Rider's Harbour at the eastern extremity of Random Island and "Harts Easse" at the entrance to Random Sound were settled much earlier. Indeed, these two settlements together with Ireland's Eye near the eastern end of Random Island, were locations of British migratory fishing activity in Trinity Bay throughout the l600s and 1700s. "Harts Easse" was the old English name for Heart's Ease Beach. One of the earliest references to the name "Random" is found on the 1689 Thornton's map of Newfoundland which shows Southwest Arm as River Random. It is possible that the region's name can be traced to the "random" course which early vessels took when entering the region from the outer reaches of Trinity Bay. In all likelihood, however, the name is derived from the word random, one meaning of which is "choppy" or "turbulence", which appropriately describes 2 sea state conditions usually encountered at the region's outer headlands of West Random Head and East Random Head. -

This Guide Was Prepared and Written by Roberta Thomas, Contract Archivist, During the Summer of 2000

1 This guide was prepared and written by Roberta Thomas, contract archivist, during the summer of 2000. Financial assistance was provided by the Canadian Council of Archives, through the Association of Newfoundland and Labrador Archives. This guide was updated by Pamela Hayter, October 6, 2010. This guide was updated by Daphne Clarke, February 8, 2018. Clarence Dewling, Archivist TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 List of Holdings ........................................................ 3 Business Records ...................................................... 7 Church and Parish Records .................................... 22 Education and Schools…………………………..52 Courts and Administration of Justice ..................... 65 Societies and Organizations ................................... 73 Personal Papers ..................................................... 102 Manuscripts .......................................................... 136 Index……………………………………………2 LIST OF THE HOLDINGS OF THE TRINITY 3 HISTORICAL SOCIETY ARCHIVES BUSINESS RECORDS Slade fonds, 1807-1861. - 84 cm textual records. E. Batson fonds, 1914 – 1974 – 156.40 cm textual records Grieve and Bremner fonds, 1863-1902 (predominant), 1832-1902 (inclusive). - 7.5 m textual records Hiscock Family Fonds, 1947 – 1963 – 12 cm textual records Ryan Brothers, Trinity, fonds, 1892 - 1948. – 6.19 m textual records Robinson Brooking & Co. Price Book, 1850-1858. - 0.5 cm textual records CHURCH AND PARISH RECORDS The Anglican Parish of Trinity fonds - 1753 -2017 – 87.75 cm textual records St. Paul=s Anglican Church (Trinity) fonds. - 1756 - 2010 – 136.5 cm textual records St. Paul’s Guild (Trinity) ACW fonds – 1900 – 1984 – 20.5 cm textual records Church of the Holy Nativity (Little Harbour) fonds, 1931-1964. - 4 cm textual records St. Augustine=s Church (British Harbour) fonds, 1854 - 1968. - 9 cm textual records St. Nicholas Church (Ivanhoe) fonds, 1926-1964. - 4 cm textual records St. George=s Church (Ireland=s Eye) fonds, 1888-1965. -

Rental Housing Portfolio March 2021.Xlsx

Rental Housing Portfolio Profile by Region - AVALON - March 31, 2021 NL Affordable Housing Partner Rent Federal Community Community Housing Approved Units Managed Co-op Supplement Portfolio Total Total Housing Private Sector Non Profit Adams Cove 1 1 Arnold's Cove 29 10 39 Avondale 3 3 Bareneed 1 1 Bay Bulls 1 1 10 12 Bay Roberts 4 15 19 Bay de Verde 1 1 Bell Island 90 10 16 116 Branch 1 1 Brigus 5 5 Brownsdale 1 1 Bryants Cove 1 1 Butlerville 8 8 Carbonear 26 4 31 10 28 99 Chapel Cove 1 1 Clarke's Beach 14 24 38 Colinet 2 2 Colliers 3 3 Come by Chance 3 3 Conception Bay South 36 8 14 3 16 77 Conception Harbour 8 8 Cupids 8 8 Cupids Crossing 1 1 Dildo 1 1 Dunville 11 1 12 Ferryland 6 6 Fox Harbour 1 1 Freshwater, P. Bay 8 8 Gaskiers 2 2 Rental Housing Portfolio Profile by Region - AVALON - March 31, 2021 NL Affordable Housing Partner Rent Federal Community Community Housing Approved Units Managed Co-op Supplement Portfolio Total Total Housing Goobies 2 2 Goulds 8 4 12 Green's Harbour 2 2 Hant's Harbour 0 Harbour Grace 14 2 6 22 Harbour Main 1 1 Heart's Content 2 2 Heart's Delight 3 12 15 Heart's Desire 2 2 Holyrood 13 38 51 Islingston 2 2 Jerseyside 4 4 Kelligrews 24 24 Kilbride 1 24 25 Lower Island Cove 1 1 Makinsons 2 1 3 Marysvale 4 4 Mount Carmel-Mitchell's Brook 2 2 Mount Pearl 208 52 18 10 24 28 220 560 New Harbour 1 10 11 New Perlican 0 Norman's Cove-Long Cove 5 12 17 North River 4 1 5 O'Donnels 2 2 Ochre Pit Cove 1 1 Old Perlican 1 8 9 Paradise 4 14 4 22 Placentia 28 2 6 40 76 Point Lance 0 Port de Grave 0 Rental Housing Portfolio Profile by Region - AVALON - March 31, 2021 NL Affordable Housing Partner Rent Federal Community Community Housing Approved Units Managed Co-op Supplement Portfolio Total Total Housing Portugal Cove/ St. -

CARBONEAR the District of Trinity

TRINITY – CARBONEAR The District of Trinity – Carbonear shall consist of and include all that part of the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador bounded as follows: Beginning at the intersection of the western shoreline of Conception Bay and the Town of Harbour Grace Municipal Boundary (1996); Thence running in a general southwesterly and southeasterly direction along the said Municipal Boundary to its intersection with the Parallel of 47o40’ North Latitude; Thence running due west along the Parallel of 47o40’ North Latitude to its intersection with the Meridian of 53o25’ West Longitude; Thence running due north along the Meridian of 53o25’ West Longitude to its intersection with the Town of Heart’s Delight-Islington Municipal Boundary (1996); Thence running west along the said Municipal Boundary to its intersection with the eastern shoreline of Trinity Bay; Thence running in a general northeasterly and southwesterly direction along the sinuosities of Trinity Bay and Conception Bay to the point of beginning, together with all islands adjacent thereto. All geographic coordinates being scaled and referenced to the Universal Transverse Mercator Map Projection and the North American Datum of 1983. Note: This District includes the communities of Bay de Verde, Carbonear, Hant's Harbour, Heart's Content, Heart's Delight-Islington, Heart's Desire, New Perlican, Old Perlican, Salmon Cove, Small Point-Adam's Cove-Blackhead-Broad Cove, Victoria, Winterton, New Chelsea-New Melbourne-Brownsdale-Sibley's Cove-Lead Cove, Turks Cove, Grates Cove, Burnt Point-Gull Island-Northern Bay, Caplin Cove-Low Point, Job's Cove, Kingston, Lower Island Cove, Red Head Cove, Western Bay-Ochre Pit Cove, Freshwater, Perry's Cove, and Bristol's Hope. -

Live / Work / Play

E COMMUNITY PROFIL live / work / play Introduction Glovertown’s history and way of life has been shaped by its location – Situated on the edge of the ocean, and at the mouth of the Terra Nova River. Drawing influence from the sea and the land, Glovertown has a rich history of boatbuilding and logging. The surrounding waterways feed into Alexander Bay, supporting both commercial and sport fishing. Outdoor enthusiasts can boat, canoe, kayak, and fish the waters around Glovertown to experience what we have for generations. Close by, Terra Nova National Park is a jewel in our province, where forest meets sea and the views impress. Uniquely located… a national park and provincial capital to the east, the diverse communities and landscapes of the central region to the west. The beauty of the area surrounding Glovertown makes it a favourite destination. Winter or summer, Glovertown offers the best of Newfoundland experiences for travellers and residents alike. Glovertown is a community that is edging towards significant growth. Our community is well-suited to new and growing families with a safe, healthy environment. A number of services are available for senior “Glovertown’s history and way of life living, with a strong community tradition of active service groups. A competitive market provides opportunities for new home builders has been shaped by its location” to live in a rural setting or for retirees to build a dream home in a beautiful community. Opportunities for business exist in the tourism and manufacturing industries, with an ideal location for businesses that operate throughout the island. Our Community Profile will show you what Glovertown has to offer.