In Cold Blood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quadling Country

Quadling Country The Quadling Country is the southern portion of Oz. The people there favor the color red. It is ruled by the Good Witch of the South, Glinda the Good. Bunbury The path to Bunbury seemed little traveled, but it was distinct enough and ran through the trees in a zigzag course until it finally led them to an open space filled with the queerest houses Dorothy had ever seen. They were all made of crackers laid out in tiny squares, and were of many pretty and ornamental shapes, having balconies and porches with posts of bread-sticks and roofs shingled with wafer- crackers. There were walks of bread-crusts leading from house to house and forming streets, and the place seemed to have many inhabitants. When Dorothy, followed by Billina and Toto, entered the place, they found people walking the streets or assembled in groups talking together, or sitting upon the porches and balconies. And what funny people they were! Men, women and children were all made of buns and bread. Some were thin and others fat; some were white, some light brown and some very dark of complexion. A few of the buns, which seemed to form the more important class of the people, were neatly frosted. Some had raisins for eyes and currant buttons on their clothes; others had eyes of cloves and legs of stick cinnamon, and many wore hats and bonnets frosted pink and green. -- The Emerald City of Oz Although it’s not clear if Glinda was responsible for the creation of Bunbury, it is definitely possible. -

The Cowardly Lion

2. “What a mercy that was not a pike!” a. Who said this? b. What do you think would a pike have done to Jeremy? Ans: a. Jeremy said this. b. A pike would have eaten Jeremy. THE COWARDLY LION A. Answer in brief. 1. Where were Dorothy and her friends going and why? Ans: Dorothy and her friends, the Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman, were walking through the thick woods to reach the Emerald City to meet the Great Wizard of Oz. 2. What did the Cowardly Lion do to the Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman while they were walking through the forest? Ans: With one blow of his paw,the Cowardly Lion sent the Scarecrow spinning over and over to the edge of the road. Then he struck at the Tin Woodman with his sharp claws. 3. Why did the Cowardly Lion decide to go with them and what did they all do? Ans: The lion wanted to ask Oz to give him courage as his life was simply unbearable without a bit of courage. So, they set off upon the journey, the Cowardly Lion walking by Dorothy’s side. B. Answer in detail. 1. What did the lion reply when Dorothy asked him why he was a coward? Ans: When Dorothy asked him why he was a coward, the lion said that it was a mystery. He felt he might have been born that way. He learned that if he roared very loudly, every living thing was frightened and got away from him. But whenever there was danger, his heart began to beat fast. -

Baum's Dorothy and the Power of Identity

Pay 1 Camille Pay Baum’s Dorothy and the Power of Identity Discussions of Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz have highlighted the relationship between Dorothy as an individual and Oz as a whole. When this relationship is put into the context of change in American identity, one can see how Dorothy’s identity connects to the new- found identity of the middle-class American. Just before Baum wrote The Wizard , American identity had gone through a large shift. Because of a greater wage for the rising middle class, individuals found themselves playing a key role in their communities. Of course, there was a tension between the old American identity and the new American identity; and, dealing with this tension became the duty of authors (“American” 27.) Even as this change in identity was present, critics chose to focus on the political impact of Dorothy as a character in The Wizard . Most critics see Dorothy as the beginning of political change. An example of this is the work of J. Jackson Barlow, who argues that not only did Dorothy commence Oz’s change from an uncivilized land to a civilized land, but that this change was democratic (8). David Emerson agrees that Dorothy’s influence was felt in Oz, but he thinks that Dorothy’s role is to be the “motivating will (fire)” behind her and her companions achieving their goal (5). Littlefield adds to the conversation of Barlow and Emerson by inserting that even though Dorothy was the one to produce change, Dorothy gets involved in the politics of Oz, only to leave Oz to go “home” to Kansas. -

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz L. Frank Baum The preparer of this public-domain (U.S.) text is unknown. The Project Gutenberg edi- tion (“wizoz10”) was converted to LATEX using GutenMark software and re-edited (for for- matting only) by Ron Burkey. Report prob- lems to [email protected]. Revision B1 differs from B in that “—-” has everywhere been re- placed by “—”. Revision: B1 Date: 01/29/2008 Contents Introduction 1 The Cyclone 3 The Council with the Munchkins 9 How Dorothy Saved the Scarecrow 17 The Road Through the Forest 25 The Rescue of the Tin Woodman 31 The Cowardly Lion 39 The Journey to the Great Oz 45 The Deadly Poppy Field 53 The Queen of the Field Mice 61 The Guardian of the Gate 67 The Wonderful City of Oz 75 The Search for the Wicked Witch 89 The Rescue 103 The Winged Monkeys 109 i ii The Discovery of Oz, the Terrible 117 The Magic Art of the Great Humbug 129 How the Balloon Was Launched 135 Away to the South 141 Attacked by the Fighting Trees 147 The Dainty China Country 153 The Lion Becomes the King of Beasts 161 The Country of the Quadlings 165 Glinda The Good Witch Grants Dorothy’s Wish 169 Home Again 175 Introduction Folklore, legends, myths and fairy tales have followed childhood through the ages, for every healthy youngster has a wholesome and in- stinctive love for stories fantastic, marvelous and manifestly unreal. The winged fairies of Grimm and Andersen have brought more hap- piness to childish hearts than all other human creations. -

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz & Glinda of Oz Ebook, Epub

THE WONDERFUL WIZARD OF OZ & GLINDA OF OZ PDF, EPUB, EBOOK L. Frank Baum | 304 pages | 06 Jul 2012 | Wordsworth Editions Ltd | 9781840226942 | English | Herts, United Kingdom The Wonderful Wizard of Oz & Glinda of Oz PDF Book She explains "I have lived here many years Glinda plays the most active role in finding and restoring Princess Ozma , the rightful heir, to the throne of Oz, the search for whom takes place in the second book, The Marvelous Land of Oz , although Glinda had been searching for Ozma ever since the princess disappeared as a baby. Baum's children's novel The Wonderful Wizard of Oz refers to Glinda as the "Good Witch of the South"; she does not appear in the novel until late in its development. With the army quickly approaching Finley, China Girl, and finally Oz fall after her. She was old then and considered ugly by the cruel King Oz, thus causing him to brand her a witch. And Instead initiated a long grueling search across all the land of Oz, for the rightful ruler of royal blood. As the series draws to an end, Glinda telepathically contacts and saves Dorothy from falling to her death from a tower, following a confrontation with the Nome King and his minions. It is revealed that she wishes to wed Aiden, the Wizard of Oz. Glinda occasionally exhibits a more ruthless, cunning side than her counterparts or companions. In the books, Glinda is depicted as a beautiful young woman with long, rich rare red hair and blue eyes, wearing a pure white dress. -

Antelope Class Writing Term 6, Week 3 Learning- 15.6.20 the Wonderful Wizard of Oz

Antelope Class Writing Term 6, Week 3 learning- 15.6.20 The Wonderful Wizard of Oz Hello Antelopes, well done for all of your hard work so far. This week, we are going to begin a 3 week fantasy story focus by looking at ‘The Wonderful Wizard of Oz’. It has been a pleasure to see the learning that has been taking place, and we look forward to hearing more about that this week. Please send a picture or scan of your writing to [email protected], either every couple of days or at the end of the week. There are 5 lessons and each lesson will take approximately 30-40 minutes. Miss McMillan and Mrs Smith Lesson 1 To understand the events of a text. This lesson, you are going to become familiar with ‘The Wizard of Oz’ and answer questions about the text. Context • ‘The Wonderful Wizard of Oz’ is a high fantasy novel, written by L. Frank Baum, published in 1900. It was the first published of 14 novels in the Oz series and it is the best known among all the author’s books. • Most of the novels are set in Oz, a land full of wonder, strange rules and mythical beings. • In the story, Dorothy lives in Kansas (America) on her aunt and uncle’s farm. One day, a huge tornado carries her house into the sky. She lands in the fantastical Land of Oz. • Dorothy meets three friends and they travel together to the Emerald City - to visit the Wizard and ask for his help. -

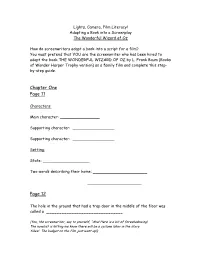

Chapter One Page 11 Page 12

Lights, Camera, Film Literacy! Adapting a Book into a Screenplay The Wonderful Wizard of Oz How do screenwriters adapt a book into a script for a film? You must pretend that YOU are the screenwriter who has been hired to adapt the book THE WONDERFUL WIZARD OF OZ by L. Frank Baum (Books of Wonder Harper Trophy version) as a family film and complete this step- by-step guide. Chapter One Page 11 Characters: Main character: ________________ Supporting character: _________________ Supporting character: _________________ Setting: State: ___________________ Two words describing their home: ______________________ ______________________ Page 12 The hole in the ground that had a trap door in the middle of the floor was called a _______________________________ (You, the screenwriter, say to yourself, “Aha! Here is a bit of foreshadowing! The novelist is letting me know there will be a cyclone later in the story. Yikes! The budget on the film just went up!) Pages 13 & 14 - a picture page. Page 15 As Aunt Em has been described on pages 12 & 13, would you write funny lines or serious lines of dialogue for her? _____________________ Based on the novelist’s descriptions of Aunt Em and Uncle Henry, who would get more lines of dialogue? _______________________ (“Uh, oh…the director has to work with a dog.”) The story opens with the family worried about ___________________. Pages 16, 17, 18 (“Yep…The cyclone. “) Look at your LCL! 3x3 Story Path Act I. (“Wait,” you say. These steps have hardly been developed at all. In the script, I must add more. I’m not sure what yet, but as I read on, I will look for ideas.”) Chapter Two Pages 19 & 20 - a picture page. -

The Wizard of Oz a Musical Extravaganza

Grand Opera House HARRY L. HAMLIN, Manager Fourth Week, Monday Evening;, June 13, 1904. FRED R. HAMLIN Presents THE WIZARD OF OZ A MUSICAL EXTRAVAGANZA. Book and Lyrics by L. Frank Baum. Music by Paul Tietjens and A. Baldwin Sloane. The entire production arranged and staged by Julian Mitchell. LIST OF CHARACTERS: (Arranged in the order of their entrance upon thestage.) ACT I. Scene 1—AKansas Farm. (Painted by Fred Gibson from designs by Walter W. Burridge.) Dorothy Gale, a Kansas girl, the victim of a cyclone Anna Laughlin The Cow, named Imogene, Dorothy's playmate Joseph Schrode Golfman Irving Christian Farm Hands Misses Fisher, Donalson, Von Brune, Murray, Gerard, Wilton, Arnold. Messrs. Cleveland, Devlin, Young. PROGRAMME CONTINUED ON NEXT PAGE We Use Exclusively and Serve Free to Patrons of this Theatre Corrinnis Waukesha Water FROM WAUKESHA WHITE ROCK SPRING WISCONSIN HINCKLEY & SCHMITT (inc.) distributers 132-134 NO. JEFFERSON ST. TELEPHONES MONROE 1507-1609 The Conover Piano, furnished by The Cable Company, is used ex- clusively in this theatre. About You Yourself would never think of mentioning to Perhaps YOU may have some facial YOUa friend some facial disfigurement of blemish which makes others uncomfortable, his own. Delicacy would forbid. Yet but which no one ever mentioned to you. how often are you positively uncomfortable in If you have it's your own fault because by the presence of some one with ill-shapen or my methods all these defers can be easily, scarred features, a broken nose or protruding painlessly and permanently corrected. ears. Birthmarks Eyes that Squint Ears that Project Noses Humped Tattoo Marks Puffy, Baggy Lids Ears that Lop Over Crooked or Flat Powder Marks Crows' Feet Hare Lips Broad or Narrow All these are Serious Blemishes which require the attention ofa Specialist. -

Sample File Is So-So

Heroes by testing their abilities and getting What is “The Lost them to spend Story points. Also, Make sure their Troubles are brought into play. This Unicorn of Oz?” adventure was written with Lye, Na'iya, Lulu and Naynda's shortcomings in mind. Temp Greetings, adventurers of Oz. This is the first in them with Story Points. a line of adventures for Instant Oz, designed to Cutaway scenes be played with minimum preparation and used with the premade Heroes found in the Instant In the Oz books, the action isn't always Oz rules. As an option, one of the players can centered on the main characters. In The play the Secondary character, Ceros, so a Emerald City of Oz, the story alternates filled-out Hero Record for him has been between Dorothy with her aunt and uncle and provided. the Nome King's general, Guph. While this kind of thing is good storytelling in the books, it Players: Unless you want the story contained in might be boring for the players to just listen to this document to be spoiled for you, please put the Historian go on about what's not happening this down and let the Historian use it. However, to their characters, so if you choose to use if you do catch some glimpses of the story here, cutaway scenes, give players the roles of the be a dear and pretend you didn't see it. characters playing out the scene. Remember, your Hero doesn't know this stuff, even if you do. It is possible that what the secondary characters are doing will cause problems for the Heroes Historian: Make sure you read this adventure later. -

![[PDF] the Emerald City of Oz L. Frank Baum, John R. Neill](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6597/pdf-the-emerald-city-of-oz-l-frank-baum-john-r-neill-2776597.webp)

[PDF] the Emerald City of Oz L. Frank Baum, John R. Neill

[PDF] The Emerald City Of Oz L. Frank Baum, John R. Neill - pdf download free book The Emerald City Of Oz by L. Frank Baum, John R. Neill Download, Read Online The Emerald City Of Oz E-Books, The Emerald City Of Oz Full Collection, Read Best Book Online The Emerald City Of Oz, Free Download The Emerald City Of Oz Full Version L. Frank Baum, John R. Neill, pdf download The Emerald City Of Oz, Download Free The Emerald City Of Oz Book, pdf L. Frank Baum, John R. Neill The Emerald City Of Oz, the book The Emerald City Of Oz, L. Frank Baum, John R. Neill ebook The Emerald City Of Oz, Download Online The Emerald City Of Oz Book, Download The Emerald City Of Oz E-Books, Read The Emerald City Of Oz Online Free, Pdf Books The Emerald City Of Oz, Read The Emerald City Of Oz Ebook Download, The Emerald City Of Oz PDF read online, Free Download The Emerald City Of Oz Best Book, The Emerald City Of Oz Free PDF Download, The Emerald City Of Oz Free PDF Online, The Emerald City Of Oz Book Download, CLICK HERE FOR DOWNLOAD pdf, mobi, epub, azw, kindle Description: From School Library Journal Grade 4 Up?If only the superior production values of this audiobook were in service to a better story. The fine vocal characterizations by the actors and actresses really bring the characters to life. To children unaccustomed to read-aloud tapes, using several readers instead of only one will help listeners distinguish who is who. -

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz a Six-Part Audio Drama by Aron Toman a Crossover

The Chronicles of Oz: The Wonderful Wizard Of Oz __________________________ A six-part audio drama by Aron Toman A Crossover Adventures Production www.crossovers.org 221. EPISODE SIX 72 PREVIOUSLY: Catch up on all the events of the previous five episodes. OPENING CREDITS 73 INT. THRONE ROOM The Scarecrow, Tin Woodman and Lion stress about the growing noise of an angry crowd outside. Dorothy rushes down the stairs. OMBY AMBY (distorted) Great Oz? The people are coming, we need you! TIN WOODMAN The Wizard? DOROTHY Gone. Little bastard did a runner in a balloon. He’ll be sailing way across the skies and away from responsibility as we speak. TIN WOODMAN Great. LION That explains why the crowd outside sounds worse than it did before. DOROTHY Crowd? TIN WOODMAN They must have seen his balloon take off. Now they’ve all got questions. LION Questions they’re going to ask us. DOROTHY Questions we can’t really answer. I mean how do you tell people 'oh, oops, sorry, your great ruler isn’t as wonderful as you thought. He’s really a big phoney and rather than (MORE) 222. DOROTHY (cont'd) tell you all himself he’s decided to run away and let these nobodies pass it on instead. Nobodies who, by the way, just killed two other significant people of government in your country and it’s gonna look darn suspicious that the Wizard disappeared just as you showed up'. TIN WOODMAN You’ve put a lot of thought into this. DOROTHY It’s a long staircase. SCARECROW I think we should tell them. -

Released Passages and Questions from PARCC

Released Passages and Questions from PARCC 1 2 3 1. Part A Read this sentence from paragraph 15 of the passage. “What can I do for you?” she inquired softly, for she was moved by the sad voice in which the man spoke. What is the meaning of the word inquired in the sentence? (RL4.4, L4.4) a. accepted b. admitted c. argued d. asked 2. Part B Which detail from the passage best provides clues from the meaning of the word inquired? a. “…. Toto barked sharply and made a snap at the tin legs…” (paragraph 12) b. “… no one has ever heard me before or come to help me.” (paragraph 14) c. “… if I am well oiled I shall soon be all right again.” (paragraph 16) d. “You will find an oil-can on a shelf in my cottage.” (paragraph 16) 4 3. Part A Why does Scarecrow question Dorothy when she says in paragraph 2 that they “must go and search for water”? (RL4.3) a. He is happy that she wants to go into the woods to get food. b. He is afraid to go into the woods toward the groaning noise. c. He does not understand why she needs the water. d. He does not want to wait for her anyone. 4. Part A Which paragraph in the passage best supports the answer to Part A? a. paragraph 4 b. paragraph 5 c. paragraph 6 d. paragraph 7 5 5. Part A Read the sentence from paragraph 22 of the passage. So they oiled his legs until he could move them freely; and he thanked them again and again for his release, for he seemed a very polite creature, and very grateful.