Boctor of ^I)Tios;Opi)]T)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Femicide – a Global Issue That Demands Action, Volume IV

“In the nineteenth century, the central moral challenge was slavery. In the twenteth century, it was the batle against totalitarianism. We believe that in this century the paramount moral challenge will be the struggle for gen- der equality around the world.” Nicholas D. Kristof, Half the Sky: Turning Oppression into Opportunity for Women Worldwide “No child should have to fear going to school. No child should ever have to fear being a child. And no child should ever have to fear being a girl.” PhumzileMlambo-Ngcuka, Executve Director, UN Women “Women subjected to contnuous violence and living under conditons of gender-based discriminaton and threat are always on – death-row, always in fear of executon.” Rashida Manjoo Former UN Special Rapporteur on Violence against Women, its Causes and Consequences VOLUME IV ISBN:978- 3- 200- 03012-1 Published by the Academic Council on the United Natons System (ACUNS) Vienna Liaison Ofce Email: [email protected] Web: www.acuns.org / www.acunsvienna.org © 2015 Academic Council on the United Natons System (ACUNS) Vienna Liaison Ofce Fourth Editon Copyright: All rights reserved. The contents of this publicaton may be freely used and copied for educatonal and other non-commercial purposes, provided that any such reproducton is accompanied by an acknowledge- ment of the authors of the artcles. Compiled and Edited: Milica Dimitrijevic, Andrada Filip, Michael Platzer Edited and formated: Khushita Vasant, Vukasin Petrovic Proofread/*Panama protocol summarized by Julia Kienast, Agnes Steinberger Design: Milica Dimitrijevic, Andrada Filip, Vukasin Petrovic Photo: Karen Castllo Farfán This publicaton was made possible by the generous fnancial contributon of the Thailand Insttute of Justce, the Karen Burke Foundaton and the Organizaton of the Families of Asia and the Pacifc. -

HONOR KILLING and BYSTANDER INTERVENTION Garima Jain Dr

Stöckl, Heidi, et al. “The global prevalence of intimate partner homicide: a systematic review.” The Lancet 382.9895 (2013): 859-865. Stump, Doris. “Prenatal sex selection.” Report from the Committee on Equal Opportunities for Women and Men. Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (2011). Tabukashvili, Marina. Georgia-A Century from Within. Tbilisi: Taso Foundation, 2011. Print. Tsuladze G,.Maglaperidze N.,Vadachkoria A. Demographic Yearbook of Georgia, Tbilisi, 2012. Barometer, Caucasus. 2010.”Dataset.” Caucasus Research Resource Center. Georgian Reproductive Health Survey (GEORHS10). IDFI.2014.Statistics of Murders in Georgia. https://idfi.ge/ge/statistic_of_murders_in_georgia NCDC/JSI.2012.Maternal Mortality Study: Georgia 2011. Georgian National Center for Disease Cntrol and Public Health, JSI Inc. Tbilisi. Vienna Declaration (2012). Vienna Symposium on Femicide, held on 26 November 2012 at the United Nations Office at Vienna recognized that femicide is the killing of women and girls because of their gender, see the declaration here:http://www.icwcif.com/phocadownload/newsletters/Vienna%20Declaration%20 on%20Femicide_%20Final.pdf. UNFPA Georgia.2014.Population Situation Analysis (PSA). Final Report. World Bank, 2014, Maria Davalos, Giorgia Demarchi, Nistha Sinha. Missing girls in the South Caucasus. Presentation. Conference organized by UNFPA. “Caucasus: Causes, consequences and policy options to address skewed sex ratios at birth. Presentation. Tbilisi International Conference on prenatal sex selection”. 4.7. HONOR RESTORED -

Euthanasia: a Review on Worldwide Legal Status and Public Opinion

Euthanasia: a review on worldwide legal status and public opinion a b Garima Jain∗ , Sanjeev P. Sahni∗ aJindal Institute of Behavioural Sciences, O.P. Jindal Global University, India bJindal Institute of Behavioural Sciences, O.P. Jindal Global University, India Abstract The moral and ethical justifiability of euthanasia has been a highly contentious issue. It is a complex concept that has been highly discussed by scholars all around the world for decades. Debates concerning euthanasia have become more frequent during the past two decades. The fact that polls show strong public support has been used in legislative debates to justify that euthanasia should be legalised. However, critics have questioned the validity of these polls. Nonetheless, the general perceptions about life are shifting from a ‘quantity of life’ to a ‘quality of life approach’, and from a paternalist approach to that of the patient’s autonomy. A ‘good death’ is now being connected to choice and control over the time, manner and place of death. All these developments have shaped discussion regarding rights of the terminally ill to refuse or discontinue life- sustaining efforts or to even ask for actively ending their life. Key words: euthanasia, ethics, public opinion, law. 1. Background The moral and ethical justifiability of euthanasia has been a highly contentious issue. It is a complex concept that has been highly discussed by scholars all around the world for decades. One of the earliest definitions of euthanasia, by Kohl and Kurtz, states it as “a mode or act of inducing or permitting death painlessly as a relief from suffering” (Beauchamp & Davidson, 1979: 295). -

The Legal Implications of Ectogenetic Research

Tulsa Law Review Volume 10 Issue 2 1974 The Legal Implications of Ectogenetic Research Kevin Abel Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Kevin Abel, The Legal Implications of Ectogenetic Research, 10 Tulsa L. J. 243 (2013). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tlr/vol10/iss2/4 This Casenote/Comment is brought to you for free and open access by TU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tulsa Law Review by an authorized editor of TU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abel: The Legal Implications of Ectogenetic Research THE LEGAL IMPLICATIONS OF ECTOGENETIC RESEARCH Kevin Abel The really revolutionary revolution is to be achieved, not in the external world, but in the souls and flesh of human beings. Aldous Huxley INTRODUCTION In 1961, Dr. Daniele Petrucci of the University of Bologna, Italy, was conducting experiments in human ectogenesis, the in vitro' fertili- zation and gestation of a fetus.2 Dr. Petrucci had succeeded in nutur- ing from fertilization a human embryo for twenty-nine days; then he detected abnormalities in the embryo and "terminated" the experi- ment.3 In another effort, Petrucci succeeded in sustaining an ecto- genetic embryo for almost two months;4 it died due to a laboratory mis- take.5 When word of Dr. Petrucci's experiments reached the Italian public it created a furor.6 Petrucci was blasted by civic leaders and the Vatican. 7 Demands were even made that the doctor be prosecuted for murder. -

Female Infanticide in 19Th-Century India: a Genocide?

Advances in Historical Studies, 2014, 3, 269-284 Published Online December 2014 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/ahs http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ahs.2014.35022 Female Infanticide in 19th-Century India: A Genocide? Pramod Kumar Srivastava Department of Western History, University of Lucknow, Lucknow, India Email: [email protected] Received 15 September 2014; revised 19 October 2014; accepted 31 October 2014 Copyright © 2014 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract In post-colonial India the female foeticide, a practice evolved from customary female infanticide of pre-colonial and colonial period, committed though in separate incidents, has made it almost a unified wave of mass murder. It does not fulfil the widely accepted existing definition of genocide but the high rate of abortion of legitimate girl-foetus by Indian parents makes their crime a kind of group killing or genocide. The female foeticide in post-colonial India is not a modern phenomenon but was also prevalent in pre-colonial India since antiquity as female infanticide and the custom continued in the 19th century in many communities of colonial India, documentation of which are widely available in various archives. In spite of the Act of 1870 passed by the Colonial Government to suppress the practice, treating it a murder and punishing the perpetrators of the crime with sentence of death or transportation for life, the crime of murdering their girl children did not stop. During a period of five to ten years after the promulgation of the Act around 333 cases of female infanticide were tried and 16 mothers were sentenced to death, 133 to transportation for life and others for various terms of rigorous imprisonment in colonial India excluding British Burma and Assam where no such crime was reported. -

Download File

SOWCmech2 12/9/99 5:29 PM Page 1 THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2000 e yne THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2000 The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) © The Library of Congress has catalogued this serial publication as follows: Any part of THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2000 The state of the world’s children 2000 may be freely reproduced with the appropriate acknowledgement. UNICEF, UNICEF House, 3 UN Plaza, New York, NY 10017, USA. ISBN 92-806-3532-8 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.unicef.org UNICEF, Palais des Nations, CH-1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland Cover photo UNICEF/92-702/Lemoyne Back cover photo UNICEF/91-0906/Lemoyne THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2000 Carol Bellamy, Executive Director, United Nations Children’s Fund Contents Foreword by Kofi A. Annan, Secretary-General of the United Nations 4 The State of the World’s Children 2000 Reporting on the lives of children at the end of the 20th century, The State of the World’s Children 5 2000 calls on the international community to undertake the urgent actions that are necessary to realize the rights of every child, everywhere – without exception. An urgent call to leadership: This section of The State of the World’s Children 2000 appeals to 7 governments, agencies of the United Nations system, civil society, the private sector and children and families to come together in a new international coalition on behalf of children. It summarizes the progress made over the last decade in meeting the goals established at the 1990 World Summit for Children and in keeping faith with the ideals of the Convention on the Rights of the Child. -

Forms of Femicide

29 Forms of Femicide Facilitate. Educate. Collaborate. The opinions expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the AUTHOR views of the Government of Ontario or the Nicole Etherington, Research Associate, Learning Network, Centre for Research & Education on Violence Centre for Research and Education on Violence Against Women Against Women & Children. While all and Children, Faculty of Education, Western University. reasonable care has been taken in the preparation of this publication, no liability is assumed for any errors or omissions. SUGGESTED CITATION Etherington, N., Baker, L. (June 2015). Forms of Femicide. Learning Network Brief (29). London, Ontario: Learning The Learning Network is an initiative of the Network, Centre for Research and Education on Violence Centre for Research & Education on Violence Against Women and Children. against Women & Children, based at the http://www.vawlearningnetwork.ca Faculty of Education, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada. Download copies at: http://www.vawlearningnetwork.ca/ Copyright: 2015 Learning Network, Centre for Research and Education on Violence against Women and Children. www.vawlearningnetwork.ca Funded by: Page 2 of 5 Forms of Femicide Learning Network Brief 29 Forms of Femicide Femicide is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as ‘the intentional killing of women because they are women; however, a broader definition includes any killings of women and girls.’i Femicide is the most extreme form of violence against women on the continuum of violence and discrimination against women and girls. There are numerous manifestations of femicide recognized by the Academic Council on the United Nations System (ACUNS) Vienna Liaison Office. ii It is important to note that the following categories of femicide are not always discrete and may overlap in some instances of femicide. -

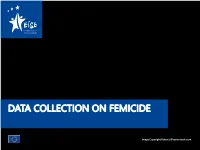

Data Collection on Femicide

DATA COLLECTION ON FEMICIDE Image Copyright:fizkes's/Shutterstock.com CHALLENGES FOR DATA COLLECTION • No international defintion of “femicide” • Terminology of femicide not adapted to statistical purposes • Lack of disaggregated approaches to data collection • Technical obstacles in data collection at national level LEGISLATIVE CONTEXT Victims’ Istanbul Rights Convention Directive Report of CEDAW GR UNODC 35 (49) (2019) & Road Map DEFINITIONS BY ACADEMIA The killing of females by males because they are females (Russell, D. 1976) The murder of women by men motivated by hatred, contempt, pleasure or a sense of ownership over women (Caputi and Russell 1990) The misogynistic killings of women by men (Radford & Russell, 1992) DEFINITIONS OF INTERNATIONAL ORGANISATIONS Vienna WHO MESECVI ICCS Declaration (UN) Femicide is the The The violent killing of women An unlawful death killing of women and intentional because because of gender, inflicted upon a girls because of their murder of whether it occurs within the person with the gender women family, domestic unit or any intent to cause because they other interpersonal death or serious are women relationship, within the injury community, by any individual or when committed or tolerated by the state or its agents, either by act or omission COMPONENTS Intentional Killing 24 Death related to unsafe abortion 14 FGM-related death 9 Killing of a partner or espouse 7 Gender-based act and/or killing of a woman 6 Death of women resultinf of IPV 5 COMPONENTS OF FEMICIDE OF COMPONENTS Dowry-related deaths Females foeticide Honour-based Killings 0 10 20 30 NUMBER OF MEMBER STATES COMPONENTS KEY COMPONENTS Gender Gender inequalities motivation EIGE’s DEFINITION AND INDICATOR The killing of a woman by an intimate partner and the death of a woman as a result of a practice that is harmful to women. -

Reportingon Violence and Girls

Reporting on Violence against Women and Girls A Handbook for Journalists Published in 2019 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France ©UNESCO 2019 ISBN 978-92-3-100349-3 This publication is available in Open Access under the Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO (CC-BY-SA 3.0 IGO) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/igo/). By using the content of this publication, the users accept to be bound by the terms of use of the UNESCO Open Access Repository (http://en.unesco.org/open- access/terms-use-ccbysa-en). Original title Informer sur les violences à l’égard des filles et des femmes : manuel pour les journalistes. Published in 2019 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author; they are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. Author: Anne-Marie Impe Editor: Mirta Lourenço Cover illustration: LanaBrest / iStock/Getty Images Plus Graphic design and layout: ©Strategic Agenda UK Ltd Printed in France The translation to English of this handbook was made possible thanks to the financial support of the Canadian Commission for UNESCO. Foreword In the age of digital, democratic, societal and political change, communication has become a crucial means of conveying revolutionary ideas and initiatives, capable of creating communities that are stronger, better informed and more engaged than ever before. -

Information on Gender-Related Killing of Women and Girls Provided by Civil Society Organizations and Academia

UNODC/CCPCJ/EG.8/2014/CRP.2 3 November 2014 English only Expert Group on gender-related killing of women and girls Bangkok, 11-13 November 2014 Item 4 of the provisional agenda* Discussion on ways and means to more effectively prevent, investigate, prosecute and punish gender-related killing of women and girls Information on gender-related killing of women and girls provided by civil society organizations and academia Contents Page I. Introduction ................................................................... 2 II. Definitions and contextual background ............................................. 2 III. Statistics and surveys ........................................................... 3 IV. Role of civil society in promoting international and national laws — the Istanbul Convention 5 V. Prevention measures and strategies ................................................ 6 VI. Protection ..................................................................... 8 VII. Investigation and prosecution ..................................................... 9 VIII. Victim and family support services and compensation ................................ 12 IX. Recommendations .............................................................. 12 Annex ............................................................................. 14 __________________ * UNODC/CCPCJ/EG.8/2014/1. V.14-07303 (E) *1407303* UNODC/CCPCJ/EG.8/2014/CRP.2 I. Introduction 1. In its resolution 68/191, entitled “Taking action against gender-related killing of women and girls”, the General -

Abortion and Preterm Birth: Why Medical Journals Aren’T Giving Us the Real Picture

IORG International Organizations Research Group Briefing Paper Number 9 April 28, 2012 Abortion and Preterm Birth: Why Medical Journals Aren’t Giving Us The Real Picture By Byron Calhoun, M.D. Catholic Family & Human Rights Institute C FAM N E W YO R K • WA SHINGT O N , D C FOREWORD In “Abortion and Preterm Birth: Why Medical Journals Aren’t Giving Us The Real Picture,” Dr. Byron Calhoun reviews the pertinent literature concerning the risk factors for preterm birth and concludes that medical journals, and particularly some authors, un- dervalue or even minimize the link between abortions (either spontaneous or induced) and subsequent risk of preterm birth. Dr. Calhoun believes that everyone involved in women’s health should be aware of the correlation between previous abortions and preterm birth, and that women should have access to appropriate counseling on the matter. Preterm birth is of paramount importance because the long-term disabilities it causes and the costs it incurs place an onerous burden on families, doctors, and society. Although it is not possible to distinguish between the relative effects of spontane- ous versus induced abortion on preterm birth from current studies, researchers should not minimize the overall undisputed relationship between abortion and preterm birth. Doing so has thus far resulted in inaccurate conclusions. I believe that Dr. Calhoun’s conclusions are highly appropriate and that the studies he evaluates are the most important in the English-language scientific literature. Policy makers would do well to enact appropriate policies according to his analysis. Gian Carlo Di Renzo, M.D., Ph.D. -

Public Health Impact of Legal Termination of Pregnancy in the US: 40 Years Later

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Scienti�ca Volume 2012, Article ID 980812, 16 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.6064/2012/980812 Review Article Public Health Impact of Legal Termination of Pregnancy in the US: 40 Years Later John M. Thorp Jr. Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, School of Medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA Correspondence should be addressed to John M. orp Jr.; [email protected] Received 6 September 2012; Accepted 15 October 2012 Academic Editors: M. W. Davies, T. B. Henriksen, and J. Keelan Copyright © 2012 John M. orp Jr. is is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. During the 40 years since the US Supreme Court decision in Doe versus Wade and Doe versus Bolton, restrictions on termination of pregnancy (TOP) were overturned nationwide. e use of TOP was much wider than predicted and a substantial fraction of reproductive age women in the U.S. have had one or more TOPs and that widespread uptake makes the downstream impact of any possible harms have broad public health implications. While short-term harms do not appear to be excessive, from a public perspective longer term harm is conceiving, and clearly more study of particular relevance concerns the associations of TOP with subsequent preterm birth and mental health problems. Clearly more research is needed to quantify the magnitude of risk and accurately inform women with the crisis of unintended pregnancy considering TOP. e current US data-gathering mechanisms are inadequate for this important task.