History-Of-The-Methodist-Church-Ghana.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music of Ghana and Tanzania

MUSIC OF GHANA AND TANZANIA: A BRIEF COMPARISON AND DESCRIPTION OF VARIOUS AFRICAN MUSIC SCHOOLS Heather Bergseth A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTERDecember OF 2011MUSIC Committee: David Harnish, Advisor Kara Attrep © 2011 Heather Bergseth All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT David Harnish, Advisor This thesis is based on my engagement and observations of various music schools in Ghana, West Africa, and Tanzania, East Africa. I spent the last three summers learning traditional dance- drumming in Ghana, West Africa. I focus primarily on two schools that I have significant recent experience with: the Dagbe Arts Centre in Kopeyia and the Dagara Music and Arts Center in Medie. While at Dagbe, I studied the music and dance of the Anlo-Ewe ethnic group, a people who live primarily in the Volta region of South-eastern Ghana, but who also inhabit neighboring countries as far as Togo and Benin. I took classes and lessons with the staff as well as with the director of Dagbe, Emmanuel Agbeli, a teacher and performer of Ewe dance-drumming. His father, Godwin Agbeli, founded the Dagbe Arts Centre in order to teach others, including foreigners, the musical styles, dances, and diverse artistic cultures of the Ewe people. The Dagara Music and Arts Center was founded by Bernard Woma, a master drummer and gyil (xylophone) player. The DMC or Dagara Music Center is situated in the town of Medie just outside of Accra. Mr. Woma hosts primarily international students at his compound, focusing on various musical styles, including his own culture, the Dagara, in addition music and dance of the Dagbamba, Ewe, and Ga ethnic groups. -

Mary Grace Reich Faculty Advisor

CHRISTIAN INSTITUTIONS IN GHANAIAN POLITICS: SOCIAL CAPITAL AND INVESTMENTS IN DEMOCRACY Mary Grace Reich Faculty Advisor: Professor Shobana Shankar A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Award of Honors in Culture & Politics Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service, Georgetown University Spring 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abbreviations…………………………………………………………………………………….1 Introduction………………………………………………………...…………………………….2 Chapter 1: Historical Evolution…………………………………………………...………….14 Chapter 2: Contemporary Status……………………………………….…………………….37 Chapter 3: The December 2012 Elections………………………...………………………….57 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………….…………..….84 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………………….87 1 ABBREVIATIONS AFRC – Armed Forces Revolutionary Council AIC – African (Instituted, Initiated, Independent, Indigenous) Church CCG – Christian Council of Ghana CDD – Center for Democratic Development CHAG – Christian Health Association of Ghana CODEO Coalition of Domestic Election Observers CPP – Convention People’s Party CUCG – Catholic University College of Ghana EC – Electoral Commission ECOWAS – Economic Community of West African States FBO – Faith-based Organization GCBC – Ghana Catholic Bishops’ Conference GNA – Ghana News Agency GPCC – Ghana Pentecostal & Charismatic Council HIPC – Highly Indebted Poor Country IDEG – Institute for Democratic Governance IEA – Institute of Economic Affairs MP – Member of Parliament MoH – Ministry of Health NCS – National Catholic Secretariat NRC – National Redemption Council NDC -

1 the Impact of African Traditional Religious

The Impact of African Traditional Religious Beliefs and Cultural Values on Christian- Muslim Relations in Ghana from 1920 through the Present: A Case Study of Nkusukum-Ekumfi-Enyan area of the Central Region. Submitted by Francis Acquah to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology in December 2011 This thesis is available for library use on the understanding that it is copy right material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any university. Signature………………………………………………………. 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT My first and foremost gratitude goes to my academic advisors Prof. Emeritus Mahmoud Ayoub (Hartford Seminary, US) and Prof. Robert Gleave (IAIS, University of Exeter) for their untiring efforts and patience that guided me through this study. In this respect I, also, wish to thank my brother and friend, Prof. John D. K. Ekem, who as a Ghanaian and someone familiar with the background of this study, read through the work and offered helpful suggestions. Studying as a foreign student in the US and the UK could not have been possible without the generous financial support from the Scholarship Office of the Global Ministries, United Methodist Church, USA and some churches in the US, notably, the First Presbyterian Church, Geneseo, NY and the First Presbyterian Church, Fairfield, CT. In this regard, Lisa Katzenstein, the administrator of the Scholarship Office of the Global Ministries (UMC) and Prof. -

Notes Weekly Bible Lessons

Weekly Bible Lessons Notes Scripture, unless otherwise indicated, is taken from THE HOLY BIBLE NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION®. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 International Bible Society. Used by permission of Zondervan Bible Publishers. All rights reserved. All comments, enquiries and suggestions may be directed to: The Head, Educational Resource Development Department Freeman Centre for Missions and Leadership Development, P. O. Box 413, Kumasi, Ghana. Telephone: (051) 23014, 20968 Email: [email protected] Copyright © The Methodist Church Ghana January - June 2010 1 148 The Weekly Bible Lessons is produced biannually by the Educational Resource Development Department of the Freeman Centre for Missions and Leadership Development of The Methodist Church Ghana, under the supervision and over- sight of the Board of Ministries of the Church. This booklet is designed to facili- tate and enhance organised group Bible studies, within group (class) meetings Notes and personal devotion. Review Editor Our Writers The following writers made significant contributions to this edition of Weekly Bible Lessons, January-June 2010. Right Reverend Professor O. Safo-Kantanka, BSc., MSc., PhD. , Diocesan Bishop, Kumasi Diocese Very Reverend Dr. Paul Kwabena Boafo, BA. , Chaplain, KNUST, Kumasi. Very Reverend G. K. Abeyie Sarpong, BA., Superintendent Minister, Tutuka Circuit, Obuasi Diocese. Very Reverend (Mrs). Comfort Ruth Quartey-Papafio, MTS., ThM., Kasoa Circuit, Winneba Diocese. Very Reverend James K. Walton, BSc., MDiv., Headmaster, Methodist Day Senior High School, Tema. Rev. Daniel Kwasi Tannor, BA., MPhil., Lecturer, Christian Service University College, Kumasi. Rev. Richard E. Amissah, Evangelism Coordinator, Kumasi Diocese. Rev. Kwame Amoah Mensah., B.Ed., Diocesan Youth Organizer, Kumasi Diocese. Rev. Mark S. Aidoo, BD., MTh., Student, Princeton Theological Seminary, USA. -

Kenneth J. Collins, Ph.D. 1 Updated February 16, 2009 Primary Sources: Books Published Albin, Thomas A., and Oliver A. Becke

Kenneth J. Collins, Ph.D. Updated February 16, 2009 Primary Sources: Books Published Albin, Thomas A., and Oliver A. Beckerlegge, eds. Charles Wesley's Earliest Sermons. London: Wesley Historical Society, 1987. Six unpublished manuscript sermons. Baker, Frank, ed. The Works of John Wesley. Bicentennial ed. Vol. 25: Letters I. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1980. ---. The Works of John Wesley. Bicentennial ed. Vol. 26: Letters II. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1982. ---. A Union Catalogue of the Publications of John and Charles Wesley. Stone Mountain, GA: George Zimmerman, 1991. Reprint of the 1966 edition. Burwash, Rev N., ed. Wesley's Fifty Two Standard Sermons. Salem, Ohio: Schmul Publishing Co., 1967. Cragg, Gerald R., ed. The Works of John Wesley. Bicentennial ed. Vol. 11: The Appeals to Men of Reason and Religion and Certain Related Open Letters. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1975. Curnock, Nehemiah, ed. The Journal of Rev. John Wesley. 8 vols. London: Epworth Press, 1909-1916. Davies, Rupert E., ed. The Works of John Wesley. Bicentennial ed. Vol. 9: The Methodist Societies, I: History, Nature and Design. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1989. Green, Richard. The Works of John and Charles Wesley. 2nd revised ed. New York: AMS Press, 1976. Reprint of the 1906 edition. Hildebrandt, Franz, and Oliver Beckerlegge, eds. The Works of John Wesley. Bicentennial ed. Vol. 7: A Collection of Hymns for the Use of the People Called Methodists. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1983. Idle, Christopher, ed. The Journals of John Wesley. Elgin, Illinois: Lion USA, 1996. Jackson, Thomas, ed. The Works of Rev. John Wesley. 14 vols. London: Wesleyan Methodist Book Room, 1829-1831. -

Changes in the Music of the Liturgy of the Methodist Church Ghana: Influences on the Youth

American Research Journal of Humanities & Social Science (ARJHSS)R) 2019 American Research Journal of Humanities & Social Science (ARJHSS) E-ISSN: 2378-702X Volume-02, Issue-04, pp-30-35 April-2019 www.arjhss.com Research Paper Open Access Changes In The Music Of The Liturgy Of The Methodist Church Ghana: Influences On The Youth Daniel S. Ocran Methodist University College Dansoman Accra Ghana *Corresponding Author: Daniel S. Ocran ABSTRACT: This paper examines the current liturgy of the Methodist Church to ascertain how the youth of today have been influenced by the musical content. Musical traditions of the Methodist Church such as ebibindwom, hymns and canticles, anthems, danceable tunes from the singing band and other liturgical musical elements present in the Methodist ChurchGhana, will critically be reviewed to realise the response of the youths. The methodology of the research will include visits to selected churches in selected dioceses, interviews of choirmasters and singing band masters selected members from the congregation as well as local preachers and Reverend, Ministers to find out about how they perceive the youths response to the variants of musical styles on the liturgy. The findings will go a long way to enlighten, reform and educate various Methodist youth to adjust to the new Order of Service. I. PREAMBLE This work has four sections: the first two sections discuss the ministration and involvement of the youth in the Methodist Church Ghana. The last but one section, the bedrock in which the whole topic is based emphatically contributes to the effects of change in the music of liturgy on the youth, while the writer concludes the last section of the article by discussing in detail the negative impact of the liturgical change in the music of the Methodist Church Ghana on the youth of today. -

Black Internationalism and African and Caribbean

BLACK INTERNATIONALISM AND AFRICAN AND CARIBBEAN INTELLECTUALS IN LONDON, 1919-1950 By MARC MATERA A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History Written under the direction of Professor Bonnie G. Smith And approved by _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ _______________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May 2008 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Black Internationalism and African and Caribbean Intellectuals in London, 1919-1950 By MARC MATERA Dissertation Director: Bonnie G. Smith During the three decades between the end of World War I and 1950, African and West Indian scholars, professionals, university students, artists, and political activists in London forged new conceptions of community, reshaped public debates about the nature and goals of British colonialism, and prepared the way for a revolutionary and self-consciously modern African culture. Black intellectuals formed organizations that became homes away from home and centers of cultural mixture and intellectual debate, and launched publications that served as new means of voicing social commentary and political dissent. These black associations developed within an atmosphere characterized by a variety of internationalisms, including pan-ethnic movements, feminism, communism, and the socialist internationalism ascendant within the British Left after World War I. The intellectual and political context of London and the types of sociability that these groups fostered gave rise to a range of black internationalist activity and new regional imaginaries in the form of a West Indian Federation and a United West Africa that shaped the goals of anticolonialism before 1950. -

February 12, 2021 RUSSELL EARLE RICHEY

February 12, 2021 RUSSELL EARLE RICHEY Durham Address: 1552 Hermitage Court, Durham, NC 27707; PO Box 51382, 27717-1382 Telephone Numbers: 919-493-0724 (Durham); 828-245-2485 (Sunshine); Cell: 404-213-1182 Office Address: Duke Divinity School, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708-0968, 919-660-3565 Email: [email protected] or [email protected] Birthdate: October 19, 1941 (Asheville, NC) Parents: McMurry S. Richey, Erika M. Richey, both deceased Married to Merle Bradley Umstead (Richey), August 28, 1965. Children--William McMurry Richey, b. December 29, 1970 and Elizabeth Umstead Richey Thompson, b. March 3, 1977. William’s spouse--Jennifer (m. 8/29/98); Elizabeth’s spouse–Bennett (m. 6/23/07) Grandchildren—Benjamin Richey, b. May 14, 2005; Ruby Richey, b. August 14, 2008; Reeves Davis Thompson, b. March 14, 2009; McClain Grace Thompson, b June 29, 2011. Educational History (in chronological order); 1959-63 Wesleyan University (Conn.) B.A. (With High Honors and Distinction in History) 1963-66 Union Theological Seminary (N.Y.C.) B.D. = M.Div. 1966-69 Princeton University, M.A. 1968; Ph.D. 1970 Honors, Awards, Recognitions, Involvements and Service: Wesleyan: Graduated with High Honors, Distinction in History, B.A. Honors Thesis on African History, and Trench Prize in Religion; Phi Beta Kappa (Junior year record); Sophomore, Junior, and Senior Honor Societies; Honorary Woodrow Wilson; elected to post of Secretary-Treasurer for student body member Eclectic fraternity, inducted into Skull and Serpent, lettered in both basketball and lacrosse; selected to participate in Operation Crossroads Africa, summer 1981 Union Theological Seminary: International Fellows Program, Columbia (2 years); field work in East Harlem Protestant Parish; participated in the Student Interracial Ministry, summer 1964; served as national co-director of SIM, 1964-65. -

Aspects of Arminian Soteriology in Methodist-Lutheran Ecumenical Dialogues in 20Th and 21St Century

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto ASPECTS OF ARMINIAN SOTERIOLOGY IN METHODIST-LUTHERAN ECUMENICAL DIALOGUES IN 20TH AND 21ST CENTURY Mikko Satama Master’s Thesis University of Helsinki Faculty of Theology Department of Systematic Theology Ecumenical Studies 18th January 2009 HELSINGIN YLIOPISTO − HELSINGFORS UNIVERSITET Tiedekunta/Osasto − Fakultet/Sektion Laitos − Institution Teologinen tiedekunta Systemaattisen teologian laitos Tekijä − Författare Mikko Satama Työn nimi − Arbetets title Aspects of Arminian Soteriology in Methodist-Lutheran Ecumenical Dialogues in 20th and 21st Century Oppiaine − Läroämne Ekumeniikka Työn laji − Arbetets art Aika − Datum Sivumäärä − Sidoantal Pro Gradu -tutkielma 18.1.2009 94 Tiivistelmä − Referat The aim of this thesis is to analyse the key ecumenical dialogues between Methodists and Lutherans from the perspective of Arminian soteriology and Methodist theology in general. The primary research question is defined as: “To what extent do the dialogues under analysis relate to Arminian soteriology?” By seeking an answer to this question, new knowledge is sought on the current soteriological position of the Methodist-Lutheran dialogues, the contemporary Methodist theology and the commonalities between the Lutheran and Arminian understanding of soteriology. This way the soteriological picture of the Methodist-Lutheran discussions is clarified. The dialogues under analysis were selected on the basis of versatility. Firstly, the sole world organisation level dialogue was chosen: The Church – Community of Grace. Additionally, the document World Methodist Council and the Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification is analysed as a supporting document. Secondly, a document concerning the discussions between two main-line churches in the United States of America was selected: Confessing Our Faith Together. -

Religion, Mission and National Development

Page 1 of 6 Original Research Religion, mission and national development: A contextual interpretation of Jeremiah 29:4–7 in the light of the activities of the Basel Mission Society in Ghana (1828–1918) and its missiological implications Author: We cannot realistically analyse national development without factoring religion into the analysis. 1 Peter White In the same way, we cannot design any economic development plan without acknowledging Affiliation: the influence of religion on its implementation. The fact is that, many economic development 1Department of Science of policies require a change from old values, attitudes, beliefs and behaviour patterns of the Religion and Missiology, citizenry to those that are supportive of the new policy. Christianity has become a potent social University of Pretoria, force in every facet of Ghanaian life, from family life, economic activities, occupation, and South Africa health to education. In the light of the essential role of religion in national development, this Correspondence to: article discusses the role the Basel Mission Society played in the development of Ghana and Peter White its missiological implications. This article argues that the Basel Mission Society did not only present the gospel to the people of Ghana, they also practicalised the gospel by developing Email: [email protected] their converts spiritually, economically, and educationally. Through these acts of love by the Basel Mission Society, the spreading of the Gospel gathered momentum and advanced. Postal address: Private Bag X20, Hatfield Intradisciplinary and/or interdisciplinary implications: The article contributes to the 0028, South Africa interdisciplinary discourse on religion and development with specific reference to the role of the Basel Mission Society’s activities in Ghana (1828–1918). -

MOBA Newsletter 1 Jan-Dec 2019 1 260420 1 Bitmap.Cdr

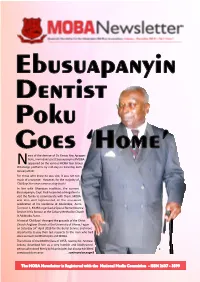

Ebusuapanyin Dentist Poku Goes ‘Home’ ews of the demise of Dr. Fancis Yaw Apiagyei Poku, immediate past Ebusuapanyin of MOBA Nappeared on the various MOBA Year Group WhatsApp plaorms by mid-day on Saturday 26th January 2019. For those who knew he was sick, it was not too much of a surprise. However, for the majority of 'Old Boys' the news came as a big shock! In line with Ghanaian tradion, the current Ebusuapanyin, Capt. Paul Forjoe led a delegaon to visit the family to commiserate with them. MOBA was also well represented at the one-week celebraon at his residence at Abelenkpe, Accra. To crown it, MOBA organised a Special Remembrance Service in his honour at the Calvary Methodist Church in Adabraka, Accra. A host of 'Old Boys' thronged the grounds of the Christ Church Anglican Church at the University of Ghana, Legon on Saturday 24th April 2019 for the Burial Service and more importantly to pay their last respects to the man who had done so much for Mfantsipim and MOBA. The tribute of the MOBA Class of 1955, read by Dr. Andrew Arkutu, described him as a very humble and kindhearted person who stood firmly by his principles but always exhibited a composed demeanor. ...connued on page 8 The MOBA Newsletter is Registered with the National Media Commision - ISSN 2637 - 3599 Inside this Issue... Comments 5 Editorial: ‘Old Boys’ - Let’s Up Our Game 6 From Ebusuapanyin’s Desk Cover Story 8. Dr. Poku Goes Home 9 MOBA Honours Dentist Poku From the School 10 - 13 News from the Hill MOBA Matters 15 MOBA Elections 16 - 17 Facelift Campaign Contributors 18 - 23 2019 MOBA Events th 144 Anniversary 24 - 27 Mfantsipim Celebrates 144th Anniversary 28 2019 SYGs Project - Staff Apartments Articles 30 - 31 Reading, O Reading! Were Art Thou Gone? 32 - 33 2019 Which Growth? Lifestyle Advertising Space Available 34 - 36 Journey from Anumle to Kotokuraba Advertising Space available for Reminiscences businesses, products, etc. -

The Educators'network 2Nd Literacy Forum

…inspiring Ghanaian teachers PRESENTS THE EDUCATORS’ NETWORK 2ND LITERACY FORUM An intensive, wide-ranging series of workshops designed for educators who are seeking to improve students’ reading and writing skills. under the theme, THE READING-WRITING CONNECTION: BOOSTING CHILDREN’S LITERACY SKILLS Saturday 24th November 2012 8:00 am – 5:30 pm at Lincoln Community School, Abelenkpe P.O. Box OS 1952, Accra Email: [email protected] …inspiring Ghanaian teachers THE PURPOSE OF THE EDUCATORS NETWORK LITERACY FORUMS Effective educators are life-long learners. Of all the factors that contribute to student learning, recent research shows that classroom instruction is the most crucial. This places teachers as the most important influence on student performance. For this reason, teachers must be given frequent opportunities to develop new instructional skills and methodologies, and share their knowledge of best practice with other teachers. It is imperative that such opportunities are provided to encourage the refining of skills, inquiry into practice and incorporation of new methods in classroom settings. To create these opportunities, The Educators’ Network (TEN) was established as a teacher initiative to provide professional development opportunities for teachers in Ghana. Through this initiative, TEN hopes to grow a professional learning community among educators in Ghana. BACKGROUND INFORMATION ON THE EDUCATORS’ NETWORK TEN was founded by a group of Ghanaian international educators led by Letitia Naami Oddoye, who are passionate about teaching and have had the benefit of exposure to diverse educational curricula and standards. Each of these educators has over ten years of experience in teaching and exposure to international seminars and conferences.