Federal Administrative Law Cases and Materials (Second Edition)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Register/Vol. 86, No. 134/Friday, July 16, 2021/Rules

37674 Federal Register / Vol. 86, No. 134 / Friday, July 16, 2021 / Rules and Regulations (Federalism), it is determined that this DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE Pennsylvania Avenue NW, Washington, action does not have sufficient DC 20530. Comments received by mail federalism implications to warrant the 28 CFR Part 50 will be considered timely if they are preparation of a Federalism Assessment. [Docket No. OAG 174; AG Order No. 5077– postmarked on or before August 16, As noted above, this action is an 2021] 2021. The electronic Federal eRulemaking portal will accept order, not a rule. Accordingly, the RIN 1105–AB61 comments until Midnight Eastern Time Congressional Review Act (CRA) 3 is at the end of that day. inapplicable, as it applies only to rules. Processes and Procedures for FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: 5 U.S.C. 801, 804(3). It is in the public Issuance and Use of Guidance Robert Hinchman, Senior Counsel, interest to maintain the temporary Documents Office of Legal Policy, U.S. Department placement of N-ethylhexedrone, a-PHP, AGENCY: Office of the Attorney General, of Justice, telephone (202) 514–8059 4-MEAP, MPHP, PV8, and 4-chloro-a- Department of Justice. (not a toll-free number). PVP in schedule I because they pose a ACTION: Interim final rule; request for SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: public health risk, for the reasons comments. expressed in the temporary scheduling I. Posting of Public Comments order (84 FR 34291, July 18, 2019). The SUMMARY: This interim final rule Please note that all comments temporary scheduling action was taken (‘‘rule’’) implements Executive Order received are considered part of the pursuant to 21 U.S.C. -

The Supreme Court and the New Equity

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 68 | Issue 4 Article 1 5-2015 The uprS eme Court and the New Equity Samuel L. Bray Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Samuel L. Bray, The uS preme Court and the New Equity, 68 Vanderbilt Law Review 997 (2019) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol68/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VANDERBILT LAW REVIEW VOLUME 68 MAY 2015 NUMBER 4 ARTICLES The Supreme Court and the New Equity Samuel L. Bray* The line between law and equity has largely faded away. Even in remedies, where the line persists, the conventional scholarly wisdom favors erasing it. Yet something surprisinghas happened. In a series of cases over the last decade and a half, the U.S. Supreme Court has acted directly contrary to this conventional wisdom. These cases range across many areas of substantive law-from commercial contracts and employee benefits to habeas and immigration, from patents and copyright to environmental law and national security. Throughout these disparate areas, the Court has consistently reinforced the line between legal and equitable remedies, and it has treated equitable remedies as having distinctive powers and limitations. This Article describes and begins to evaluate the Court's new equity cases. -

U.S. Core+ for Firms, Government Institutions, and Other Organizations

U.S. CORE+ FOR FIRMS, GOVERNMENT INSTITUTIONS, AND OTHER ORGANIZATIONS Choose HeinOnline and give your organization the competitive advantage with our premier online legal research package offering 30 databases of current and historical content. THE HEINONLINE ADVANTAGE FEATURED DATABASES IN THE PACKAGE Affordable • Brennan Center for Justice Publications • Canada Supreme Court Reports In addition to the wealth of material • Civil Rights and Social Justice - New at an incredible price, more than one • Code of Federal Regulations million pages are added to HeinOnline each month. The value of a subscription • COVID-19: Pandemics Past and Present - New increases with each content release. • Criminal Justice & Criminology • Early American Case Law • English Reports Comprehensive • European Centre for Minority Issues (ECMI) HeinOnline contains more than 3,000 • Executive Privilege - New journals on a variety of subjects. All • Fastcase (U.S. State & Federal Case Law) journals date back to inception, and • Federal Register Library more than 90% are available through the • GAO Reports and Comptroller General Decisions current issue or volume. • Gun Regulation and Legislation in America • Law Journal Library Authoritative • Legal Classics • Military and Government - New HeinOnline is composed of image-based • Open Society Justice Initiative - New PDFs, which are as authoritative as print • Pentagon Papers material for citation purposes, because • Revised Statutes of Canada they are exact facsimiles of the original print materials. • Statutes of the Realm • U.S. Code • U.S. Congressional Documents Incredible Customer Service • U.S. Congressional Serial Set HeinOnline’s support team is second to • U.S. Federal Legislative History Library none, providing users with searching • U.S. Presidential Impeachment Library - New and document retrieval assistance, • U.S. -

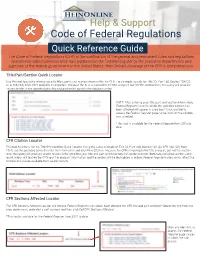

Code of Federal Regulations | Quick Reference Guide

Help & Support Help & Support Code of Federal Regulations Quick Reference Guide The Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) is the codification of the general and permanent rules and regulations (sometimes called administrative law) published in the Federal Register by the executive departments and agencies of the federal government of the United States. HeinOnline’s coverage of the CFR is comprehensive. Title/Part/Section Quick Locator Use this tool to quickly retrieve specific titles, parts, and sections from within the CFR. For example, search for Title 33, Part 160, Section 204 (33 CFR 160.204) from 2015 and click Find Section. Because the CFR is indexed to the title and part, but not the section level, this query will produce search results in the specified year, title and part which contain the section number. NOTE: After entering year, title, part, and section information, Federal Register issues in which the specified citation has been affected will appear in a red box.* Click any link to access the Federal Register page range in which the citation was affected. *This tool is available for the Federal Register from 2015 to date. CFR Citation Locator This tool functions like the Title/Part/Section Quick Locator. Using the same example of Title 33, Part 160, Section 204 (33 CFR 160.204) from 2015, use the provided boxes to enter the information and click Find Citation. Because the CFR is indexed to the title and part, but not the section level, this query will produce search results in the specified year, title and part which contain the section number. -

Form, Function, and Justiciability Anthony J

Notre Dame Law School NDLScholarship Journal Articles Publications 2007 Form, Function, and Justiciability Anthony J. Bellia Notre Dame Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/law_faculty_scholarship Part of the Other Law Commons Recommended Citation Anthony J. Bellia, Form, Function, and Justiciability, 86 Tex. L. Rev. See Also 1 (2007-2008). Available at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/law_faculty_scholarship/828 This Response or Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Form, Function, and Justiciability Anthony J. Bellia Jr.* In A Theory of Justiciability,' Professor Jonathan Siegel provides an insightful functional analysis of justiciability doctrines. He well demonstrates that justiciability doctrines are ill suited to serve certain purposes-for example, ensuring that litigants have adverse interests in disputes that federal courts hear. Professor Siegel proceeds to identify what he believes to be one plausible purpose of justiciability doctrines: to enable Congress to decide when individuals with "abstract" (or "undifferentiated") 2 injuries may use federal courts to require that federal law be enforced. Ultimately, he rejects this justification because (1) congressional power to create justiciability where it would not otherwise exist proves that justiciability is not a real limit on federal judicial power, and (2) Congress should not have authority to determine when constitutional provisions are judicially enforceable because Congress could thereby control enforcement of constitutional limitations on its own authority. -

Justice Scalia, the Nondelegation Doctrine, and Constitutional Argument William K

Notre Dame Law Review Volume 92 | Issue 5 Article 9 5-2017 Justice Scalia, the Nondelegation Doctrine, and Constitutional Argument William K. Kelley Notre Dame Law School Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr Part of the Judges Commons Recommended Citation 92 Notre Dame L. Rev. 2107 (2017) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Notre Dame Law Review at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Notre Dame Law Review by an authorized editor of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. \\jciprod01\productn\N\NDL\92-5\NDL509.txt unknown Seq: 1 15-JUN-17 10:42 JUSTICE SCALIA, THE NONDELEGATION DOCTRINE, AND CONSTITUTIONAL ARGUMENT William K. Kelley* INTRODUCTION Justice Antonin Scalia wrote two major opinions applying the nondelega- tion doctrine: in Mistretta v. United States,1 he wrote a lone dissent concluding that Congress’s establishment of the United States Sentencing Commission was unconstitutional because the Commission had been assigned no function by Congress other than the making of rules, the Sentencing Guidelines. Such “pure” lawmaking by a “junior-varsity Congress,” Justice Scalia con- cluded, was inconsistent with the Constitution’s basic division of powers.2 In Whitman v. American Trucking Ass’ns,3 he wrote for a unanimous Court upholding a very broad delegation of rulemaking power to the Environmen- tal Protection Agency (EPA), and along the way acknowledged that Con- gress’s power to assign policymaking discretion to agencies extended to raw exercises of discretion from among a range of possibilities that was appar- ently genuinely unlimited. -

Federal Register/Vol. 84, No. 248/Friday, December 27, 2019

71714 Federal Register / Vol. 84, No. 248 / Friday, December 27, 2019 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION procedures for the review and clearance Department’s rulemaking process can be of guidance documents; and (3) a found at 49 CFR 5.5. Office of the Secretary General Counsel memorandum, This final rule reflects the existing ‘‘Procedural Requirements for DOT role of the Department’s Regulatory 14 CFR Parts 11, 300, and 302 Enforcement Actions’’ (February 15, Reform Task Force in the development 2019),3 which clarifies the procedural of the Department’s regulatory portfolio 49 CFR Parts 1, 5, 7, 106, 211, 389, 553, requirements governing enforcement and ongoing review of regulations. and 601 actions initiated by the Department, Established in response to Executive including administrative enforcement Order 13777, ‘‘Enforcing the Regulatory RIN 2105–AE84 proceedings and judicial enforcement Reform Agenda’’ (February 24, 2017), Administrative Rulemaking, Guidance, actions brought in Federal court. the Regulatory Reform Task Force is the and Enforcement Procedures This final rule removes the existing Department’s internal body, chaired by procedures on rulemaking, which are the Regulatory Reform Officer, tasked AGENCY: Office of the Secretary of outdated and inconsistent with current with evaluating proposed and existing Transportation (OST), U.S. Department departmental practice, and replaces regulations and making of Transportation (DOT). them with a comprehensive set of recommendations to the Secretary of ACTION: Final rule. procedures that will increase Transportation regarding their transparency, provide for more robust promulgation, repeal, replacement, or SUMMARY: This final rule sets forth a public participation, and strengthen the modification, consistent with applicable comprehensive revision and update of overall quality and fairness of the law. -

The Political Question Doctrine: Justiciability and the Separation of Powers

The Political Question Doctrine: Justiciability and the Separation of Powers Jared P. Cole Legislative Attorney December 23, 2014 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R43834 The Political Question Doctrine: Justiciability and the Separation of Powers Summary Article III of the Constitution restricts the jurisdiction of federal courts to deciding actual “Cases” and “Controversies.” The Supreme Court has articulated several “justiciability” doctrines emanating from Article III that restrict when federal courts will adjudicate disputes. One justiciability concept is the political question doctrine, according to which federal courts will not adjudicate certain controversies because their resolution is more proper within the political branches. Because of the potential implications for the separation of powers when courts decline to adjudicate certain issues, application of the political question doctrine has sparked controversy. Because there is no precise test for when a court should find a political question, however, understanding exactly when the doctrine applies can be difficult. The doctrine’s origins can be traced to Chief Justice Marshall’s opinion in Marbury v. Madison; but its modern application stems from Baker v. Carr, which provides six independent factors that can present political questions. These factors encompass both constitutional and prudential considerations, but the Court has not clearly explained how they are to be applied. Further, commentators have disagreed about the doctrine’s foundation: some see political questions as limited to constitutional grants of authority to a coordinate branch of government, while others see the doctrine as a tool for courts to avoid adjudicating an issue best resolved outside of the judicial branch. Supreme Court case law after Baker fails to resolve the matter. -

The Nondelegation Doctrine: Alive and Well

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NDL\93-2\NDL204.txt unknown Seq: 1 28-DEC-17 10:20 THE NONDELEGATION DOCTRINE: ALIVE AND WELL Jason Iuliano* & Keith E. Whittington** The nondelegation doctrine is dead. It is difficult to think of a more frequently repeated or widely accepted legal conclusion. For generations, scholars have maintained that the doctrine was cast aside by the New Deal Court and is now nothing more than a historical curiosity. In this Article, we argue that the conventional wisdom is mistaken in an important respect. Drawing on an original dataset of more than one thousand nondelegation challenges, we find that, although the doctrine has disappeared at the federal level, it has thrived at the state level. In fact, in the decades since the New Deal, state courts have grown more willing to invoke the nondelegation doctrine. Despite the countless declarations of its demise, the nondelegation doctrine is, in a meaningful sense, alive and well. INTRODUCTION .................................................. 619 R I. THE LIFE AND DEATH OF THE NONDELEGATION DOCTRINE . 621 R A. The Doctrine’s Life ..................................... 621 R B. The Doctrine’s Death ................................... 623 R II. THE STRUCTURE OF A CONSTITUTIONAL REVOLUTION ....... 626 R III. THE PERSISTENCE OF THE NONDELEGATION DOCTRINE ...... 634 R A. Success Rate .......................................... 635 R B. Pre– and Post–New Deal Comparison .................... 639 R C. Representative Cases.................................... 643 R CONCLUSION .................................................... 645 R INTRODUCTION The story of the nondelegation doctrine’s demise is a familiar one. Eighty years ago, the New Deal Court discarded this principle, and since then, this once-powerful check on administrative expansion has had no place in our constitutional canon. -

Strategic Decision-Making and Justiciability

Deciding to Not Decide: A Longitudinal Analysis of the Politics of Secondary Access on the U.S. Supreme Court A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Andrew Povtak May 2011 Dissertation written by Andrew Povtak B.A., Case Western Reserve University, 2000 J.D., Cleveland State University, 2004 Approved by _____________________________, Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Christopher Banks _____________________________, Members, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Ryan Claassen _____________________________, Mark Colvin _____________________________, Elizabeth Smith-Pryor _____________________________, Graduate Faculty Representative Stephen Webster Accepted by ______________________________, Chair, Department of Political Science Steven Hook ______________________________, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences John R.D. Stalvey ii Table of Contents List of Tables…………………………………………………………………...iv Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………v Chapter 1 – Introduction………………………………………………………1 I. An Overview of the U.S. Supreme Court………………………...3 II. Jurisdictional and Procedural Doctrines…………………………8 III. The Elements of Justiciability: Standing, Timing, and Political Question…………………………………………11 IV. Justiciability Issues: Legal and Political Science Research…..18 V. Data and Methods………………………………………………....28 VI. Conclusion…………………………………………………………41 Chapter 2 – Assessing the Attitudinal and Legal Models…………………42 I. Literature Review: Models of Individual Justice Voting -

Justiciability of State Law School Segregation Claims Will Stancil

Mitchell Hamline Law Review Volume 44 | Issue 2 Article 1 2018 Justiciability of State Law School Segregation Claims Will Stancil Jim Hilbert Mitchell Hamline School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://open.mitchellhamline.edu/mhlr Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Education Law Commons, Law and Race Commons, and the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation Stancil, Will and Hilbert, Jim (2018) "Justiciability of State Law School Segregation Claims," Mitchell Hamline Law Review: Vol. 44 : Iss. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://open.mitchellhamline.edu/mhlr/vol44/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mitchell Hamline Law Review by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Mitchell Hamline School of Law Stancil and Hilbert: Justiciability of State Law School Segregation Claims JUSTICIABILITY OF STATE LAW SCHOOL SEGREGATION CLAIMS Will Stancil† and Jim Hilbert†† I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................... 400 II. BACKGROUND ON SCHOOLS .................................................. 402 A. Legal Basis of Public Education ...................................... 402 B. Growth of Inequality in Public Education ......................... 406 III. CORRECTING SCHOOL DISPARITIES WITH LITIGATION .......... 410 A. -

Attorney General's Manual on The

Attorney GeneraI's'Man~al on the Administrative Procedure Act WM. W. GAUNT 6' SONS, INC. Holmes Beach, Florida 33510 1973 ~ ;' Wm. W. Gaunt & Sons, Inc Reprint Edition This is an unabridged republication of the first editign published in [~H7 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 7Z-97700 International Standard Book Number 9 12004 - 11 - 4 Published by Wm. W. Gaunt & Sons, Inc. 3011 Gulf Drive, Holmes Beach, Florida 33510 Printed in the United States of America by Jones Offset, Inc., Bradenton Beach, Florida 33510 Attorney General's Manual on the Administrative Procedure Act Prepared by the United States Department of Justice TOM C. CLARK Attorney General TAnLB OF CONTENTS Pa~ INTRODUCTION . 5 Note Concerning Manner of Citation of Legi.dative MateriaL . 8 I-FuNDAMJo:NTAL CONC'EPTIl . 9 •.\. •• ~a..lic PurpO!le:lof the, ~dmin.htra~ive Procedure Act . 9 b. Coverage of the Admlm:ltrallve I roeedure Act.. : . 9 :=) c. Distinction between Hille Making an<1 Adjudieation .. 12 ,/ . II-SeCTION 3, PUBLIC INfORMATION. .. 17 .. Agencies Subject to Section 3 . 17 Exceptions to Requirement! of Section 3........... .. 17 (1) Any function of the United State3 rerluiring secrecy in the public interest . 17 (2) Any matter relatinlf !lo]rdy to the internal management of an agency.. 18 Effective Date-Pro3pectlve Operation............. .. 18 SECTION 3 (a)-RULES...................................... 19 Separate Statement._.................... 19 Description of Organization......... 19 Statement of Procedures. .. 20 Substantive Rules.................... .. .. 22 Section 3 (b)-Opinions and Or'!eri............ 23 24 1I~~~T:o~C)~Kt~~C fi~~~[~~.::: .• :::::.::.. :.. :::::::::::::·::::::::::::.:::::::::::::::::::~::: 26 Exceptions (1) Any military, naval, or foreign alTairs function of the United StatelJ...