The Bibliotheca Sacra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AN OVERVIEW and CRITIQUE of the NEW PERSPECTIVE on PAUL's DOCTRINE of JUSTIFICATION: Part Two-The New Perspective Critiqued (1) Jeffery Smith'

AN OVERVIEW AND CRITIQUE OF THE NEW PERSPECTIVE ON PAUL'S DOCTRINE OF JUSTIFICATION: Part Two-The New Perspective Critiqued (1) Jeffery Smith' In a previous article I sought to give an overview of what has been called "The New Perspective on Paul"l. Specific focus was given to those aspects of the New Perspective (NP) that most directly touch on the doctrine of justification by faith. We considered its leading proponents, primary tenets, growing influence, subtle appeal, and alarming implications. In this and following articles, we will take up a summary critique of the NP. This article will address historical and hermeneutical problems with the NP. Those to follow will take up some of its exegetical problems. The Historical Problem with the New Perspective: Was 2nd Temple Judaism Really a Religion of Grace? As we saw in the previous article, much of the NP approach to Paul is based on the assertion that 2nd Temple Judaism was a religion of grace. One might argue that this assertion is the Iynchpin, the keystone, the foundation, the cornerstone, the bedrock of the NP. This assertion (or assumption) is primarily based on the conclusions of E.P. Sanders in his Paul and Palestinian Judaism. It all starts with Sanders. James Dunn puts it this way: Judaism is first and foremost a religion of grace ... Somewhat surprisingly, the picture Sanders painted of what he called covenant nom ism is remarkably like the classic Reformation theology of works .... that good works are the consequence and outworking of divine grace, not the means by which that grace is first attained ... -

Ancient Church History Semi-Pelagianism, Semi-Augustinianism, and the Synod of Orange (529) Pastor Charles R

Ancient Church History Semi-Pelagianism, Semi-Augustinianism, and the Synod of Orange (529) Pastor Charles R. Biggs Review of Pelagius and Augustine/ Council of Ephesus (431) Pelagius was a British monk, a very zealous preacher who was castrated for the sake of the kingdom and given to rigorous asceticism. He desired to live a life of perfect holiness. In Christian history, he has come to be the arch-heretic of the church, but in his early writings he was very orthodox and sought to maintain and uphold the creeds of the early church. Pelagius came from Rome to Carthage in the year 410 AD (after Alaric I had captured Rome) with his friend and student Celestius. He taught the people of North Africa a new emphasis on morals and the rigorous life of living the Gospel, because he was shocked by the low tone of Roman morals and thought that Augustine’s teaching on divine grace contributed to the immorality. Celestius, who was the most prominent follower of Pelagius at the time, was condemned at the Council of Carthage in 411 because he denied the transmission of Adam’s sins to his descendants. Augustine began to write and preach again Pelagius and Celestius’ doctrines. Pelagius and Celestius were condemned at two councils at Carthage and Milevis (Numidia, North Africa) in 416 and Innocent I (410-17) excommunicated them from the church. On May 1, 418 the Council of Carthage convened to issue a series of nine canons affirming without compromise the Augustinian doctrine of the Fall and Original Sin. Emperor Honorius (395-423) issued an imperial decree denouncing the teachings of Pelagius and Celestius in that same year. -

Trinitarian/Christological Heresies Heresy Description Origin Official

Trinitarian/Christological Heresies Official Heresy Description Origin Other Condemnation Adoptionism Belief that Jesus Propounded Theodotus was Alternative was born as a by Theodotus of excommunicated names: Psilanthro mere (non-divine) Byzantium , a by Pope Victor and pism and Dynamic man, was leather merchant, Paul was Monarchianism. [9] supremely in Rome c.190, condemned by the Later criticized as virtuous and that later revived Synod of Antioch presupposing he was adopted by Paul of in 268 Nestorianism (see later as "Son of Samosata below) God" by the descent of the Spirit on him. Apollinarism Belief proposed Declared to be . that Jesus had by Apollinaris of a heresy in 381 by a human body Laodicea (died the First Council of and lower soul 390) Constantinople (the seat of the emotions) but a divine mind. Apollinaris further taught that the souls of men were propagated by other souls, as well as their bodies. Arianism Denial of the true The doctrine is Arius was first All forms denied divinity of Jesus associated pronounced that Jesus Christ Christ taking with Arius (ca. AD a heretic at is "consubstantial various specific 250––336) who the First Council of with the Father" forms, but all lived and taught Nicea , he was but proposed agreed that Jesus in Alexandria, later exonerated either "similar in Christ was Egypt . as a result of substance", or created by the imperial pressure "similar", or Father, that he and finally "dissimilar" as the had a beginning declared a heretic correct alternative. in time, and that after his death. the title "Son of The heresy was God" was a finally resolved in courtesy one. -

Pelagianism Michael S. Horton

Pelagianism Michael S. Horton We possess neither the ability, free will, power, nor the righteousness to repair ourselves and escape the wrath of God. It must all be God's work, Christ's work, or there is no salvation. Cicero observed of his own civilization that people thank the gods for their material prosperity, but never for their virtue, for this is their own doing. Princeton theologian B. B. Warfield considered Pelagianism "the rehabilitation of that heathen view of the world," and concluded with characteristic clarity, "There are fundamentally only two doctrines of salvation: that salvation is from God, and that salvation is from ourselves. The former is the doctrine of common Christianity; the latter is the doctrine of universal heathenism." (1) But Warfield's sharp criticisms are consistent with the witness of the church ever since Pelagius and his disciples championed the heresy. St. Jerome, the fourth century Latin father, called it "the heresy of Pythagoras and Zeno," as in general paganism rested on the fundamental conviction that human beings have it within their power to save themselves. What, then, was Pelagianism and how did it get started? First, this heresy originated with the first human couple, as we shall see soon. It was actually defined and labeled in the fifth century, when a British monk came to Rome. Immediately, Pelagius was deeply impressed with the immorality of this center of Christendom, and he set out to reform the morals of clergy and laity alike. This moral campaign required a great deal of energy and Pelagius found many supporters and admirers for his cause. -

John Wesley, Irenaeus, and Christian Mission: Rethinking Western Christian Theology

The Asbury Journal 73/1: 138-159 © 2018 Asbury Theological Seminary DOI: 10.7252/Journal.01.2018S.07 Howard A. Snyder John Wesley, Irenaeus, and Christian Mission: Rethinking Western Christian Theology Abstract John Wesley (1703-1791) was a theologian and practitioner of mission. The theological sophistication of his missiology has never been fully appreciated for three reasons: 1) Wesley seldom used the language of “mission,” 2) he intentionally masked the depth of his learning in the interest of “plain, sound English,” and 3) interpreters assumed that as an evangelist, Wesley could not be taken seriously as theologian. Quite to the contrary, this article shows the depth and sophistication of Wesley’s doctrinal and missiological thinking. Reviewing Western Christian theology from the frst century to our day, this article examines the close use of Irenaeus by Wesley, which carries high potency for Christian fdelity, discipleship, theological integrity, authentic mission, and Spirit-powered transformation in persons and culture. Keywords: John Wesley, Irenaeus, mission, theology, recapitulation Howard A. Snyder is currently the International Representative for the Manchester Wesley Research Centre in Manchester, UK. He is a former Professor of Wesley Studies at Tyndale Seminary in Toronto, Canada and a former Professor of the History and Theology of Mission at Asbury Theological Seminary in Wilmore, KentucKy. 138 snyder: John Wesley, irenaeus, and christian mission 139 Introduction John Wesley (1703-1791) was a theologian and practitioner of mission. The theological sophistication of his missiology has never been fully appreciated for three reasons: 1) Wesley seldom used the language of “mission,” 2) he intentionally masked the depth of his learning in the interest of “plain, sound English,”1 and 3) interpreters assumed that as an evangelist, Wesley could not be taken seriously as theologian. -

Systematic Theology 1 THEO5300 New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary Theological and Historical Studies Division Fall 2019

Systematic Theology 1 THEO5300 New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary Theological and Historical Studies Division Fall 2019 Grader: Rev John Kwak Peter W. Kendrick, ThD [email protected]. Professor of Theology and Culture Phone: 770-500-6439 North Georgia Extension Center Phone:678-802-7201 Email: [email protected] Classes Meet: Monday 1:00-2:50 PM EST 8/26, 9/9, 9/23, 10/7, 10/21, 11/4, 11/18, 12/2 Mission Statement The mission of New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary is to equip leaders to fulfill the Great Commission and the Great Commandments through the local church and its ministries. Core Value Focus The seminary has five core values: Doctrinal Integrity, Spiritual Vitality, Mission Focus, Characteristic Excellence, and Servant Leadership. The core value focus for this academic year is Spiritual Vitality: We are a worshiping community emphasizing both personal spirituality and gathering together as a Seminary family for the praise and adoration of God and instruction in His Word. Curriculum Competencies All graduates of NOBTS are expected to have at least a minimum level of competency in each of the following areas: Biblical Exposition, Christian Theological Heritage, Disciple Making, Interpersonal Skills, Servant Leadership, Spiritual and Character Formation, and Worship Leadership. The curriculum competency addressed in this course is Christian Theological Heritage. Course Description This first course in systematic theology introduces the student to the methodology of the study of theology (Prolegomena), and the doctrines of revelation, God, humanity, and the person of Christ. The biblical foundation and the relevant historical development are considered in comprehensive construction of a Christian understanding of each doctrine. -

Voluntas Dei January 2019 Team Lesson Gaudete Et Exsultate Apostolic Exhortation of Pope Francis on the Call to Holiness in Today’S World

VOLUNTAS DEI JANUARY 2019 TEAM LESSON GAUDETE ET EXSULTATE APOSTOLIC EXHORTATION OF POPE FRANCIS ON THE CALL TO HOLINESS IN TODAY’S WORLD Opening Prayer: Ever present and compassionate God, As we continue to welcome this New Year, may we remain ever conscious of your love, your mercy and your call to us to give witness to our ministry in the midst of the world. May we strive to keep things in perspective, rejoicing in the gifts you have given us, but keenly aware that those gifts are intended to be used in service of Your people, especially the poor and vulnerable. Each of us, as members of the Voluntas Dei family, have the privilege and responsibility to “act with justice, love with tenderness and walk humbly with our God.” {Micah 6”8} May this love, humility and care for justice be genuine, heartfelt and run deep within us. We so need your strength, guidance and encouragement as we seek to continue the ministry and example of Fr. Parent and those who have gone before us. We pray for all members of our Voluntas family and for those who gather at this moment for this time of reflection and sharing. May our time together remind us of our deep connection, friendship and common ministry. In Your most holy name we pray. Amen. Chapter 2: TWO Subtle Enemies of Holiness Contemporary Gnosticism This entire articles speaks about the Gnosticism and Pelagianism. In the first part of the article it is very clearly discussed about three major points, “An intellect without knowledge, A Doctrine without mystery and the limits of reason. -

Lesson 3Final.Pptx

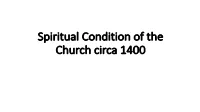

Spiritual Condition of the Church circa 1400 Heresies Confronted 1. Gnosticism. Denied Christ’s humanity. Up to 90 A.D. 2. Marcionism. Rejected Old Testament as Christian Scripture. 144 A.D. 3. Manichaeism. Similar to Gnosticism. 242 A.D. 4. Arianism. Christ is a created being and not God by nature. 320 A.D. 5. Nestorianism. Mary birthed only the human part of Jesus. 428 A.D. 6. Pelagianism. Man can achieve salvation by works. 431 A.D. Development of the Creeds 1. The Creeds were developed to address heresies and to establish Biblical support for Christian Doctrine. 2. The Apostles Creed. 197 A.D. 3. The Nicene Creed. 325 – 381 A.D. 4. The Athanasian Creed. Circa 367 A.D. (An element of the debate of the Nicene Creed by Athanasius.) Early Bible Translations 1. Original languages of the Bible were Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek. 2. Jerome translated the entire Bible into Latin by 404 A.D. Often referred to as the Latin Vulgate. 3. The Bible was translated into 13 other languages by 500 A.D. 4. Bede translated the Gospel of John into English in 720 A.D. 5. Cyril & Methodius translated the Bible into Slavic in 861 A.D. 6. Wycliffe translated the entire Bible into English in 1382 A.D. Worship & Music 1. The Latin Mass was developed over time to become the standard Sunday worship experience. The Mass was intended to allow the worshippers to join Christ in His suffering and death. The Lord’s Supper was included and the laity were served only the Bread. -

Tischner's Dispute with Kołakowski Over Grace and Freedom

logos_i_ethos_2021_(57), s. 261–292 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15633/lie.4041 Rev. Miłosz Hołda https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0649-2168 The Pontifical University of John Paul II in Krakow Tischner’s dispute with Kołakowski over grace and freedom Introduction Rev. Miłosz Hołda, a doctor of philoso- phy with a habilitation degree, an assis- The dispute over the problem tant professor at the Department of Meta- concerned with the relationship physics and Philosophy of Man, the Facul- between grace and freedom en- ty of Philosophy at the Pontifical University of John Paul II in Cracow, a lecturer at the gaged in by Saint Augustine and John Paul II Catholic University of Lub- Pelagius is not merely an interest- lin. He has authored three books and sev- ing element in the history of human eral dozen research papers, and was award- ed the prize of the President of the Coun- thought. This controversy, which cil of Ministers for the rewarded doctoral had been generated centuries ago, dissertation in 2013. His most recent pub- has been many a time revived, and lication is Źródło i noc. Wprowadzenie do współczesnego absconditeizmu [The Spring still continues, undergoing new and the Night. An Introduction to Contem- stages. One of these, which is ad- porary Absconditheism] (Kraków 2020). dressed in the present text, is the He specializes in natural theology, philoso- stage of Józef Tischner’s dispute phy of man, and epistemology. He is a mem- ber of the Internationale-Ferdinand-Ebner- with Leszek Kołakowski. Tischner -Gesellschaft. was earnest about Kołakowski’s in- terpretation of one of the stages of this controversy, i.e. -

Anti-Pelagianism and the Resistibility of Grace

Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers Volume 22 Issue 2 Article 5 4-1-2005 Anti-Pelagianism and the Resistibility of Grace Richard Cross Follow this and additional works at: https://place.asburyseminary.edu/faithandphilosophy Recommended Citation Cross, Richard (2005) "Anti-Pelagianism and the Resistibility of Grace," Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers: Vol. 22 : Iss. 2 , Article 5. DOI: 10.5840/faithphil200522230 Available at: https://place.asburyseminary.edu/faithandphilosophy/vol22/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faith and Philosophy: Journal of the Society of Christian Philosophers by an authorized editor of ePLACE: preserving, learning, and creative exchange. ANTI-PELAGIANISM AND THE RESISTIBILITY OF GRACE Richard Cross I argue that accepting the resistibility of grace does not entail accepting either Pelagianism or semi-Pelagianism, and offer seven models for the offer of grace that allow for the resistibility of grace: respectively, covenant theology, syner gism, and five models that posit no natural human act of acceptance (while allowing for natural human acts of resistance). Of these, I conclude that all but covenant theologies avoid serni-Pelagianism, and that all avoid Pelagianism, as defined at the Second Council of Orange. 'If anyone says that a person's free will when moved and roused by God gives no co-operation -

A Sampling of the Early Fathers of the Church on Baptism

1 St. Francis of Assisi Church Wakefield, RI RCIA Deacon P. Iacono A Sampling of the Early Fathers of the Church on Baptism Aristides, Apology, 15 (A.D. 140), in ANF, X: 277-27 "And when a child has been born to one of them[ ie Christians], they give thanks to God[ie baptism]; and if moreover it happen to die in childhood, they give thanks to God the more, as for one who as passed through the world without sins." St. Irenaeus, Against Heresies, 2, 22: 4 (A.D. 180), in ANF, I: 391 "For He came to save all through means of Himself--all, I say, who through Him are born again to God--infants, and children, and youths, and old men." St. Hippolytus of Rome, Apostolic Tradition, 21 (c. A.D. 215), in AT, 33 "And they shall baptize the little children first. And if they can answer for themselves, let them answer. But if they cannot, let their parents answer or someone from their family." St. Gregory Nazianzen, Oration on Holy Baptism, 40:17 (A.D. 381), "Have you an infant child? Do not let sin get any opportunity, but let him be sanctified from his childhood…” St. Ambrose, Abraham, 2, 11:79 (A.D. 387), in JUR, 2:169 " 'Unless a man be born again of water and the Holy Spirit, he cannot enter the kingdom of God.' No one is excepted: not the infant, no one…” [Pelagius, and his heresy Pelagianism, denied original sin and Christian grace] St. Augustine, On forgiveness of sin, and baptism, 39 [26] (A.D. -

Aspects of Judaising in Pelagianism in Light of Rabbinic and Patristic Exegesis of Genesis

WILL AND GRACE: ASPECTS OF JUDAISING IN PELAGIANISM IN LIGHT OF RABBINIC AND PATRISTIC EXEGESIS OF GENESIS Burton L. Visotzky Jewish Theological Seminary Pelagius lived at Kardanoel And taught a doctrine there How, whether you went to heaven or to hell It was your own affair. It had nothing to do with the Church, my boy, But was your own affair. No, he didn’t believe In Adam and Eve He put no faith therein! His doubts began With the Fall of Man And he laughed at Original Sin.1 Poor Pelagius. It was not enough that he and his followers were roundly thrashed by the invective of St. Jerome and the political manoeuvres of St. Augustine in the scrum of Church doctrine; but even the likes of Hilaire Belloc felt free to lampoon him in the ensuing ruck centuries later. Pelagian theology may have helped shape Augustinian doctrine on Free Will, God’s Grace, and Original Sin, as Augustine reacted to the Pelagian challenge.2 Despite the Pelagian loss of the battle for 1 Belloc 1912, ‘The Song of the Pelagian Heresy for the Strengthening of Men’s Backs and the very Robust Out-Thrusting of Doubtful Doctrine and the Uncertain Intellec- tual.’ Belloc has a character reply to the song: ‘there is no such place as Kardanoel, and Pelagius never lived there, and his doctrine was very different from what you say.’ I first came across this ditty in 1985–86 during a sabbatical in Cambridge and Oxford, when I participated in Christopher Stead and Henry Chadwick’s ‘Senior Patristics Seminar.’ During those halcyon days, I wrote the better part of my collection, Fathers of the World: Essays in Rabbinic and Patristic Literatures (1995).