The Humanities, Research, and the Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE JANNIS A. ANTONIADIS Department of Mathematics University of Crete 71409 Iraklio,Crete Greece PERSONAL Born on 5 of September 1951 in Dryovouno Kozani, Greece. Married with Sigrid Arnz since 1983, three children : Antonios (26), Katerina (23), Karolos (21). EDUCATION-EMPLOYMENT 1969-1973: B.S. in Mathematics at the University of Thessaloniki, Greece. 1973-1976: Military Service. 1976-1979: Assistant at the University of Thessaloniki, Greece. 1979-1981: Graduate student at the University of Cologne, Germany. 1981 Ph.D. in Mathematics at the University of Cologne. Thesis advisor: Prof. Dr. Curt Meyer. 1982-1984: Lecturer at the University of Thessaloniki, Greece. 1984-1990: Associate Professor at the University of Crete, Greece. 1990-now: Professor at the University of Crete, Greece. 2003-2007 Chairman of the Department VISITING POSITIONS - University of Cologne Germany, during the period from December 1981 until Ferbruary 1983 as researcher of the German Research Council (DFG). - MPI-for Mathematics Bonn Germany, during the periods: from May until September of the year 1985, from May until September of the year 1986, from July until January of the year 1988 and from July until September of the year 1988. - University of Heidelberg Germany, during the period: from September 1993 until January 1994, as visiting Professor. University of Cyprus, during the period from January 2008 until May 2008, as visiting Professor. Again for the Summer Semester of 2009 and of the Winter Semester 2009-2010. LONG TERM VISITS: - University -

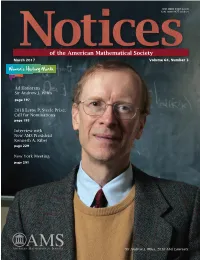

Sir Andrew J. Wiles

ISSN 0002-9920 (print) ISSN 1088-9477 (online) of the American Mathematical Society March 2017 Volume 64, Number 3 Women's History Month Ad Honorem Sir Andrew J. Wiles page 197 2018 Leroy P. Steele Prize: Call for Nominations page 195 Interview with New AMS President Kenneth A. Ribet page 229 New York Meeting page 291 Sir Andrew J. Wiles, 2016 Abel Laureate. “The definition of a good mathematical problem is the mathematics it generates rather Notices than the problem itself.” of the American Mathematical Society March 2017 FEATURES 197 239229 26239 Ad Honorem Sir Andrew J. Interview with New The Graduate Student Wiles AMS President Kenneth Section Interview with Abel Laureate Sir A. Ribet Interview with Ryan Haskett Andrew J. Wiles by Martin Raussen and by Alexander Diaz-Lopez Allyn Jackson Christian Skau WHAT IS...an Elliptic Curve? Andrew Wiles's Marvelous Proof by by Harris B. Daniels and Álvaro Henri Darmon Lozano-Robledo The Mathematical Works of Andrew Wiles by Christopher Skinner In this issue we honor Sir Andrew J. Wiles, prover of Fermat's Last Theorem, recipient of the 2016 Abel Prize, and star of the NOVA video The Proof. We've got the official interview, reprinted from the newsletter of our friends in the European Mathematical Society; "Andrew Wiles's Marvelous Proof" by Henri Darmon; and a collection of articles on "The Mathematical Works of Andrew Wiles" assembled by guest editor Christopher Skinner. We welcome the new AMS president, Ken Ribet (another star of The Proof). Marcelo Viana, Director of IMPA in Rio, describes "Math in Brazil" on the eve of the upcoming IMO and ICM. -

A Glimpse of the Laureate's Work

A glimpse of the Laureate’s work Alex Bellos Fermat’s Last Theorem – the problem that captured planets moved along their elliptical paths. By the beginning Andrew Wiles’ imagination as a boy, and that he proved of the nineteenth century, however, they were of interest three decades later – states that: for their own properties, and the subject of work by Niels Henrik Abel among others. There are no whole number solutions to the Modular forms are a much more abstract kind of equation xn + yn = zn when n is greater than 2. mathematical object. They are a certain type of mapping on a certain type of graph that exhibit an extremely high The theorem got its name because the French amateur number of symmetries. mathematician Pierre de Fermat wrote these words in Elliptic curves and modular forms had no apparent the margin of a book around 1637, together with the connection with each other. They were different fields, words: “I have a truly marvelous demonstration of this arising from different questions, studied by different people proposition which this margin is too narrow to contain.” who used different terminology and techniques. Yet in the The tantalizing suggestion of a proof was fantastic bait to 1950s two Japanese mathematicians, Yutaka Taniyama the many generations of mathematicians who tried and and Goro Shimura, had an idea that seemed to come out failed to find one. By the time Wiles was a boy Fermat’s of the blue: that on a deep level the fields were equivalent. Last Theorem had become the most famous unsolved The Japanese suggested that every elliptic curve could be problem in mathematics, and proving it was considered, associated with its own modular form, a claim known as by consensus, well beyond the reaches of available the Taniyama-Shimura conjecture, a surprising and radical conceptual tools. -

![Arxiv:Math/9807081V1 [Math.AG] 16 Jul 1998 Hthsbffldtewrdsbs Id O 5 Er Otl Bed-Time Tell to Years Olivia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1375/arxiv-math-9807081v1-math-ag-16-jul-1998-hthsb-dtewrdsbs-id-o-5-er-otl-bed-time-tell-to-years-olivia-311375.webp)

Arxiv:Math/9807081V1 [Math.AG] 16 Jul 1998 Hthsbffldtewrdsbs Id O 5 Er Otl Bed-Time Tell to Years Olivia

Oration for Andrew Wiles Fanfare We honour Andrew Wiles for his supreme contribution to number theory, a contribution that has made him the world’s most famous mathematician and a beacon of inspiration for students of math; while solving Fermat’s Last Theorem, for 350 years the most celebrated open problem in mathematics, Wiles’s work has also dramatically opened up whole new areas of research in number theory. A love of mathematics The bulk of this eulogy is mathematical, for which I make no apology. I want to stress here that, in addition to calculations in which each line is correctly deduced from the preceding lines, mathematics is above all passion and drama, obsession with solving the unsolvable. In a modest way, many of us at Warwick share Andrew Wiles’ overriding passion for mathematics and its unsolved problems. Three short obligatory pieces Biography Oxford, Cambridge, Royal Society Professor at Oxford from arXiv:math/9807081v1 [math.AG] 16 Jul 1998 1988, Professor at Princeton since 1982 (lamentably for maths in Britain). Very many honours in the last 5 years, including the Wolf prize, Royal Society gold medal, the King Faisal prize, many, many others. Human interest story The joy and pain of Wiles’s work on Fermat are beautifully documented in John Lynch’s BBC Horizon documentary; I par- ticularly like the bit where Andrew takes time off from unravelling the riddle that has baffled the world’s best minds for 350 years to tell bed-time stories to little Clare, Kate and Olivia. 1 Predictable barbed comment on Research Assessment It goes with- out saying that an individual with a total of only 14 publications to his credit who spends 7 years sulking in his attic would be a strong candidate for early retirement at an aggressive British research department. -

Fermat's Last Theorem, a Theorem at Last

August 1993 MAA FOCUS Fermat’s Last Theorem, that one could understand the elliptic curve given by the equation a Theorem at Last 2 n n y = x(x − a )( x + b ) Keith Devlin, Fernando Gouvêa, and Andrew Granville in the way proposed by Taniyama. After defying all attempts at a solution for Wiles’ approach comes from a somewhat Following an appropriate re-formulation 350 years, Fermat’s Last Theorem finally different direction, and rests on an amazing by Jean-Pierre Serre in Paris, Kenneth took its place among the known theorems of connection, established during the last Ribet in Berkeley strengthened Frey’s mathematics in June of this year. decade, between the Last Theorem and the original concept to the point where it was theory of elliptic curves, that is, curves possible to prove that the existence of a On June 23, during the third of a series of determined by equations of the form counter example to the Last Theorem 2 3 lectures at a conference held at the Newton y = x + ax + b, would lead to the existence of an elliptic Institute in Cambridge, British curve which could not be modular, and mathematician Dr. Andrew Wiles, of where a and b are integers. hence would contradict the Shimura- Princeton University, sketched a proof of the Taniyama-Weil conjecture. Shimura-Taniyama-Weil conjecture for The path that led to the June 23 semi-stable elliptic curves. As Kenneth announcement began in 1955 when the This is the point where Wiles entered the Ribet, of the University of California at Japanese mathematician Yutaka Taniyama picture. -

Foundations of Cataloging a Sourcebook

Foundations of Cataloging A Sourcebook Edited by Michael Carpenter and Elaine Svenonius 1985 Libraries Unlimited, Inc. • Littleton, Colorado xii- Preface 6. What criteria have been used for making fonn of name decisions in the past? Are they still relevant today? 7. What bibliographic relationships need to be built into a catalog to make it more than just a fmding list? Has thinking on this matter changed over the last 150 years? Criteria for Selection Rules for the Compilation An attempt was made to include in this sourcebook readings that provide intellectual depth and matter for thought. Most of the selected readings are well of the Catalogue known; a few, however, are little read but included as gems that deserve to be known. Panizzi's letter to Lord Ellesmere, for example, reflects in miniature the British Museum whole of the Anglo-American cataloging experience. Inevitably, the selections have an Anglo-American bias; particularly notable by their absence are representatives of the Indian and German schools. Some restriction was necessary to keep the volume to a manageable size, and, since it was felt that the literature written in English and about the Anglo-American tradition would be of most immediate Editor's Introduction interest, it is this writing that is represented. The vo lume includes relatively few recent contributions. This is a consequence of the fact that much recent writing Why should rules for a dead catalog be of interest today? is devo ted to the engineering of online catalogs and to the mechanics of interface, Because the history of cataloging shows that controversies rather than to the more philosophical issues of the purposes of the catalog and the recur, although why these controversies should be perennial means to achieve these. -

Statutes and Rules for the British Museum

(ft .-3, (*y Of A 8RI A- \ Natural History Museum Library STATUTES AND RULES BRITISH MUSEUM STATUTES AND RULES FOR THE BRITISH MUSEUM MADE BY THE TRUSTEES In Pursuance of the Act of Incorporation 26 George II., Cap. 22, § xv. r 10th Decembei , 1898. PRINTED BY ORDER OE THE TRUSTEES LONDON : MDCCCXCYIII. PRINTED BY WOODFALL AND KINDER, LONG ACRE LONDON TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I. PAGE Meetings, Functions, and Privileges of the Trustees . 7 CHAPTER II. The Director and Principal Librarian . .10 Duties as Secretary and Accountant . .12 The Director of the Natural History Departments . 14 CHAPTER III. Subordinate Officers : Keepers and Assistant Keepers 15 Superintendent of the Reading Room . .17 Assistants . 17 Chief Messengers . .18 Attendance of Officers at Meetings, etc. -19 CHAPTER IV. Admission to the British Museum : Reading Room 20 Use of the Collections 21 6 CHAPTER V, Security of the Museum : Precautions against Fire, etc. APPENDIX. Succession of Trustees and Officers . Succession of Officers in Departments 7 STATUTES AND RULES. CHAPTER I. Of the Meetings, Functions, and Privileges of the Trustees. 1. General Meetings of the Trustees shall chap. r. be held four times in the year ; on the second Meetings. Saturday in May and December at the Museum (Bloomsbury) and on the fourth Saturday in February and July at the Museum (Natural History). 2. Special General Meetings shall be sum- moned by the Director and Principal Librarian (hereinafter called the Director), upon receiving notice in writing to that effect signed by two Trustees. 3. There shall be a Standing Committee, standing . • Committee. r 1 1 t-» • 1 t> 1 consisting 01 the three Principal 1 rustees, the Trustee appointed by the Crown, and sixteen other Trustees to be annually appointed at the General Meeting held on the second Saturday in May. -

Fermat's Last Theorem and Andrew Wiles

Fermat's last theorem and Andrew Wiles © 1997−2009, Millennium Mathematics Project, University of Cambridge. Permission is granted to print and copy this page on paper for non−commercial use. For other uses, including electronic redistribution, please contact us. June 2008 Features Fermat's last theorem and Andrew Wiles by Neil Pieprzak This article is the winner of the schools category of the Plus new writers award 2008. Students were asked to write about the life and work of a mathematician of their choice. "But the best problem I ever found, I found in my local public library." Andrew Wiles. Image © C. J. Mozzochi, Princeton N.J. There is a problem that not even the collective mathematical genius of almost 400 years could solve. When the ten−year−old Andrew Wiles read about it in his local Cambridge library, he dreamt of solving the problem that had haunted so many great mathematicians. Little did he or the rest of the world know that he would succeed... Fermat's last theorem and Andrew Wiles 1 Fermat's last theorem and Andrew Wiles "Here was a problem, that I, a ten−year−old, could understand and I knew from that moment that I would never let it go. I had to solve it." Pierre de Fermat The story of the problem that would seal Wiles' place in history begins in 1637 when Pierre de Fermat made a deceptively simple conjecture. He stated that if is any whole number greater than 2, then there are no three whole numbers , and other than zero that satisfy the equation (Note that if , then whole number solutions do exist, for example , and .) Fermat claimed to have proved this statement but that the "margin [was] too narrow to contain" it. -

Antonio Panizzi Professor in London, 1828-1831*

JLIS.it 11, 1 (January 2020) ISSN: 2038-1026 online Open access article licensed under CC-BY DOI: 10.4403/jlis.it-12600 “You will be richer, but I very much doubt that you will be happier”. Antonio Panizzi professor in London, 1828-1831* Stefano Gambari(a), Mauro Guerrini(b) a) Biblioteche di Roma, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2910-9654 b) Università degli Studi di Firenze, http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1941-4575 __________ Contact: Stefano Gambari, [email protected]; Mauro Guerrini, [email protected] Received: 30 September 2019; Accepted: 8 October 2019; First Published: 15 January 2020 __________ ABSTRACT The paper offers an overview of the complex, not easy period in which Antonio Panizzi was teaching at London University (1828-1831), innovatively suggesting that “a uniform program be adopted for the study of all modern languages and literatures” and nevertheless dedicating himself to research with care and passion. In the article, the teaching materials and custom tools he quickly provided to his students for learning italian language and culture are analyzed regarding concept, structure and target: The Elementary Italian Grammar 1828, and two anthologies of prose writings: Extracts from the Italian Prose Writers, 1828, and Stories from Italian Writers with a Literal Interlinear Traduction, 1830. KEYWORDS Italian language; Italian grammar; Italian literature; Teaching materials for italian; University of London; Antonio Panizzi. CITATION Gambari, S., Guerrini., M. “«You will be richer, but I very much doubt that you will be happier». Antonio Panizzi professor in London, 1828-1831.” JLIS.it 11, 1 (January 2020): 73−88. DOI: 10.4403/jlis.it-12600. -

On Galois Representations in Theory and Praxis Gerhard Frey, University of Duisburg-Essen

On Galois Representations in Theory and Praxis Gerhard Frey, University of Duisburg-Essen One of the most astonishing success stories in recent mathematics is arithmetic geo- metry, which unifies methods from classical number theory with algebraic geometry (\schemes"). In this context an extremely important role is played by the Galois groups of base schemes like rings of integers of number fields or rings of holomor- phic functions of curves over finite fields. These groups are the algebraic analogues of topological fundamental groups, and their representations induced by the action on divisor class groups of varieties over these domains yield spectacular results like Serre's Conjecture for two-dimensional representations of the Galois group of Q, which implies for example the modularity of elliptic curves over Q and so Fermat's Last Theorem (and much more). At the same time the algorithmic aspect of arithmetical objects like lattices and ideal class groups of global fields becomes more and more important and accessible, stimulated by and stimulating the advances in theory. An outstanding result is the theorem of F. Heß and C.Diem yielding that the addition in divisor class groups of curves of genus g over finite fields Fq is (probabilistically) of polynomial complexity in g ( fixed) and log(q)(g fixed). So one could hope to use such groups for public key cryptography, e.g. for key exchange, as established by Diffie-Hellman for the multiplicative group of finite fields. But the obtained insights play not only a constructive role but also a destructive role for the security of such systems. -

Henry Stevens Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/ft258003k1 No online items Finding Aid for the Henry Stevens Papers, ca. 1819-1886 Processed by Saundra Taylor and Christine Chasey; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2002 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Henry Stevens 801 1 Papers, ca. 1819-1886 Finding Aid for the Henry Stevens Papers, ca. 1819-1886 Collection number: 801 UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Los Angeles, CA Contact Information Manuscripts Division UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Telephone: 310/825-4988 (10:00 a.m. - 4:45 p.m., Pacific Time) Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ Processed by: Saundra Taylor and Christine Chasey Encoded by: Caroline Cubé Text converted and initial container list EAD tagging by: Apex Data Services Online finding aid edited by: Josh Fiala, May 2003 © 2002 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Henry Stevens Papers, Date (inclusive): ca. 1819-1886 Collection number: 801 Creator: Stevens, Henry, 1819-1886 Extent: 71 boxes (35.5 linear ft.) Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Department of Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Abstract: Henry Stevens (1819-1886) was a London bookseller, bibliographer, publisher, and an expert on early editions of the English Bible and early voyages and travels to America. -

The British Museum Library

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924029534934 C U">VerS,,y Ubrary Z792.B86 R25 olin THE BRITISH MUSEUM LIBRARY — THE BRITISH MUSEUM LIBRARY BY GERTRUDE BURFORD RAWLINGS Author of The Sti^~ f Books, The Story of the British Coinage " How to Know Them Editor i wke of the Knyght of the Towre \ f etc., etc. ilAFTON & CO., COPTIC HOUSE, LONDON W. WILSON CO., WHITE PLAINS, N. Y. 1916 1>I HH ATM) TO ALICE PERRIN th« unuiH run limited, edikhukgh GREAT MUTAIK PREFACE This essay traverses some of the ground covered by Edwards's Lives of the Founders of the British Museum, and. the Reading-room manuals of Sims and Nichols, all long out of print. But it has its own field, and adds a little here and there, I venture to hope, to the published history of our national library. It is not intended as a guide to the Reading- room. Lists of some of the official catalogues and other publications that form so distinguished a part of the work of the British Museum are appended for the convenience of students in general. The bibliography indicates the main sources to which I am indebted for material. Gertrude Burford Rawlings. CONTENTS CHAPTER TAGE I. Steps towards a National Library . 9 II. The Cottonian Library ... 19 III. Additions to the Cottonian Library . 39 IV. The Sloane Bequest ... 46 V. The Early Days of the British Museum • • • 55 VI.