A Statistical Scoring System for Manager Voting for the Rawlings Gold Glove Award Emily K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St. Louis Cardinals (40-42) at Colorado Rockies (35-47) Game No

St. Louis Cardinals (40-42) at Colorado Rockies (35-47) Game No. 83 • Road Game No. 42 • Coors Field • Friday, July 2, 2021 RHP Johan Oviedo (0-4, 5.23) vs. RHP Chi Chi González (2-5, 5.81) RECENT REDBIRDS: The St. Louis Cardinals and Colorado Rockies play the sec- RECORD BREAKDOWN ond game of a four-game series as the Cardinals continue their 11-day, 10-game CARDINALS vs. ROCKIES All-Time Overall .........10,208-9,697 road trip through Colorado (0-1), San Francisco (July 5-7), and the Chicago All-Time (1993-2021):............................. 121-99 2021 Overall ........................... 40-42 Cubs (July 9-11) leading into the All-Star Break. in St. Louis (1993-2021): ................................... 71-42 Under Mike Shildt ...............202-169 FLIGHT PATTERN: St. Louis enters today 4th place in the NL Central, 9.0 games at Busch Stadium II (1993-2005): .................. 29-29 Busch Stadium .......................23-18 behind Milwaukee ... The last time the Cardinals were 9.0 games out of first place at Busch Stadium III (2006-21): ..................... 41-13 On the Road ............................ 17-24 was July 26, 2018 (51-51 record in 4th) ... The Cardinals are 8-9 on a stretch of in Colorado (1993-2019): ..........................51-57 Day ..........................................16-16 20 consecutive games against opponents with sub-.500 records (June 14-July 4). at Mile High Stadium (1993-94) ......................... 5-7 at Coors Field (1995-2019) .....................46-50 Night ........................................24-26 TAP THE ROCKIES: The Cardinals’ .700 win pct (21-9) against the Rockies since 2021.....................................................3-1 Spring.................................... 8-10-6 2016 is the highest in MLB, St. -

BEN MCDONALD'sauthenticity

bring your kids ages 9 and under for free PA GE major sporting events that should happen in baltimore 244 05.18 BEN MCDONALD’S authenticity has made him a fan-favorite for years, however, his transition from player to commentator was anything but seamless BY KEVIN ECK > Page 16 photography > courtesy of the baltimore orioles of the baltimore photography > courtesy VISIT BUYATOYOTA.COM FOR GREAT DEALS! buyatoyota.com UPCOMING PROMOTIONS AT ORIOLE PARK may 31- vs. May vs. 15-16 June 3 MAY 16 JUNE 1 FRIDAY FIREWORKS & MUSIC FIELD TRIP DAY POSTGAME, ALL FANS PRESENTED BY WJZ-TV PRE-REGISTERED STUDENTS STUDENT NIGHT ALL STUDENTS, SUBJECT TO AVAILABILITY JUNE 2 THE SANDLOT MOVIE NIGHT May POSTGAME, ALL FANS SPECIAL TICKET PACKAGES AVAILABLE vs. 28-30 JUNE 3 MAY 28 KIDS RUN THE BASES PRESENTED BY WEIS MARKETS ORIOLES MEMORIAL DAY T-SHIRT POSTGAME, ALL KIDS AGES 4-14 ALL FANS MAY 30 ORIOLES COOLER BACKPACK June vs. PRESENTED BY VISIT SARASOTA FIRST 20,000 FANS 15 & OVER 11-13 JUNE 12 DYLAN BUNDY BOBBLEHEAD FIRST 25,000 FANS 15 & OVER bring your kids ages 9 and under for free Issue 244 • 5.15.18 - table of contents - COVER STORY Ben’s Second Act......................................................16 Ben McDonald’s authenticity has made him a fan-favorite for years, however, his transition from player to commentator was anything but seamless By Kevin Eck play, FEATURE STORIES meet stay Sports Business w/ Baltimore Business Journal...... 08 Maryland Gaming w/ Bill Ordine ............................12 Ravens Report w/ Bo Smolka.................................... 13 Orioles Report w/ Rich Dubroff............................. -

WHITE SOX HEADLINES of NOVEMBER 20, 2017 “White Sox

WHITE SOX HEADLINES OF NOVEMBER 20, 2017 “White Sox face roster call on Clarkin, 6 more” … Scott Merkin, MLB.com “Up close, White Sox see same big potential Cubs forecasted for Dylan Cease” … Patrick Mooney, NBC Sports Chicago “Omar Vizquel will reportedly be a minor league manager for White Sox in 2018” … Vinnie Duber, NBC Sports Chicago “Frank Kaminsky on the White Sox rebuild: ‘The Process is paying off for the 76ers. I hope it pays off for us too’” … Jon Greenberg, The Athletic “Rumor Central: Athletics eyeing White Sox OF Avisail Garica as trade target?” … Nick Ostiller, ESPN.com White Sox face roster call on Clarkin, 6 more Chicago must decide which top prospects to protect from Rule 5 Draft By Scott Merkin / MLB.com | Nov. 17, 2017 CHICAGO -- By all accounts, Ian Clarkin threw the ball well during recently completed White Sox instructional league action at Camelback Ranch in Glendale, Ariz. Even more important, the left-hander felt healthy through six or seven side sessions, after dealing with myriad injuries during his Minor League career. That combination, along with his raw talent, puts Clarkin in play to be added to the White Sox 40-man roster by the 7 p.m. CT deadline on Monday, protecting him from exposure to selection by the rest of baseball in the Rule 5 Draft on Dec. 14 at the Winter Meetings in Lake Buena Vista, Fla. Clarkin, Chicago's No. 22 prospect according to MLBPipeline.com, was selected by the Yankees at No. 33 overall in the 2013 MLB Draft, one pick after Aaron Judge, the '17 American League Rookie of the Year Award winner and MVP Award runner-up. -

Page One Layout 1

Game Information ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Detroit Tigers Media Relations Department w Comerica Park w Phone (313) 471-2000 w Fax (313) 471-2138 w Detroit, MI 48201 w www.tigers.com Twitter - @DetroitTigersPR, @tigers, @TigresdeDetroit Detroit Tigers at Houston Astros Friday, June 27, 2014 Minute Maid Park, Houston, TX Game Time - 8:10 p.m. EDT RECENT RESULTS: The Tigers completed a three-game sweep of the Rangers and TIGERS AT A GLANCE extended their winning streak to seven games with a 6-0 win on Thursday night at Globe Life Park in Arlington. Rick Porcello recorded the first complete game shutout of his career, Record: 43-32 / Streak: W7 scattering three hits, walking three and striking out six. Offensively, Miguel Cabrera was 4x5 with a double and an RBI, while Nick Castellanos, Ian Kinsler and Victor Martinez each Game #76 / Road #38 added two hits in the win. The Tigers continue their nine-game road trip tonight as they Home: 19-19 / Road: 24-13 begin a three-game series against the Astros. Following this weekend’s series, the Tigers return home on Monday to start a nine-game homestand, which includes a three-game Tonight’s Scheduled Starters series versus Oakland, a four-game set against Tampa Bay and a two-game series versus the Dodgers. RHP Justin Verlander vs. RHP Brad Peacock PORCELLO GOES THE DISTANCE: Rick Porcello turned in the second complete game and (6-7, 4.82) (2-4, 4.50) first shutout of his career in last night’s 6-0 win over the Rangers. He allowed just three hits, walked three and struck out six in his nine scoreless innings. -

Seattle Mariners Opening Day Record Book

SEATTLE MARINERS OPENING DAY RECORD BOOK 1977-2012 All-Time Openers Year Date Day Opponent Att. Time Score D/N 1977 4/6 Wed. CAL 57,762 2:40 L, 0-1 N 1978 4/5 Wed. MIN 45,235 2:15 W, 3-2 N 1979 4/4 Wed. CAL 37,748 2:23 W, 5-4 N 1980 4/9 Wed. TOR 22,588 2:34 W, 8-6 N 1981 4/9 Thurs. CAL 33,317 2:14 L, 2-6 N 1982 4/6 Tue. at MIN 52,279 2:32 W, 11-7 N 1983 4/5 Tue. NYY 37,015 2:53 W, 5-4 N 1984 4/4 Wed. TOR 43,200 2:50 W, 3-2 (10) N 1985 4/9 Tue. OAK 37,161 2:56 W, 6-3 N 1986 4/8 Tue. CAL 42,121 3:22 W, 8-4 (10) N 1987 4/7 Tue. at CAL 37,097 2:42 L, 1-7 D 1988 4/4 Mon. at OAK 45,333 2:24 L, 1-4 N 1989 4/3 Mon. at OAK 46,163 2:19 L, 2-3 N 1990 4/9 Mon. at CAL 38,406 2:56 W, 7-4 N 1991 4/9 Tue. CAL 53,671 2:40 L, 2-3 N 1992 4/6 Mon. TEX 55,918 3:52 L, 10-12 N 1993 4/6 Tue. TOR 56,120 2:41 W, 8-1 N 1994 4/4 Mon. at CLE 41,459 3:29 L, 3-4 (11) D 1995 4/27 Thurs. -

Tml American - Single Season Leaders 1954-2016

TML AMERICAN - SINGLE SEASON LEADERS 1954-2016 AVERAGE (496 PA MINIMUM) RUNS CREATED HOMERUNS RUNS BATTED IN 57 ♦MICKEY MANTLE .422 57 ♦MICKEY MANTLE 256 98 ♦MARK McGWIRE 75 61 ♦HARMON KILLEBREW 221 57 TED WILLIAMS .411 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 235 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 73 16 DUKE SNIDER 201 86 WADE BOGGS .406 61 MICKEY MANTLE 233 99 MARK McGWIRE 72 54 DUKE SNIDER 189 80 GEORGE BRETT .401 98 MARK McGWIRE 225 01 BARRY BONDS 72 56 MICKEY MANTLE 188 58 TED WILLIAMS .392 61 HARMON KILLEBREW 220 61 HARMON KILLEBREW 70 57 TED WILLIAMS 187 61 NORM CASH .391 01 JASON GIAMBI 215 61 MICKEY MANTLE 69 98 MARK McGWIRE 185 04 ICHIRO SUZUKI .390 09 ALBERT PUJOLS 214 99 SAMMY SOSA 67 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 183 85 WADE BOGGS .389 61 NORM CASH 207 98 KEN GRIFFEY Jr. 67 93 ALBERT BELLE 183 55 RICHIE ASHBURN .388 97 LARRY WALKER 203 3 tied with 66 97 LARRY WALKER 182 85 RICKEY HENDERSON .387 00 JIM EDMONDS 203 94 ALBERT BELLE 182 87 PEDRO GUERRERO .385 71 MERV RETTENMUND .384 SINGLES DOUBLES TRIPLES 10 JOSH HAMILTON .383 04 ♦ICHIRO SUZUKI 230 14♦JONATHAN LUCROY 71 97 ♦DESI RELAFORD 30 94 TONY GWYNN .383 69 MATTY ALOU 206 94 CHUCK KNOBLAUCH 69 94 LANCE JOHNSON 29 64 RICO CARTY .379 07 ICHIRO SUZUKI 205 02 NOMAR GARCIAPARRA 69 56 CHARLIE PEETE 27 07 PLACIDO POLANCO .377 65 MAURY WILLS 200 96 MANNY RAMIREZ 66 79 GEORGE BRETT 26 01 JASON GIAMBI .377 96 LANCE JOHNSON 198 94 JEFF BAGWELL 66 04 CARL CRAWFORD 23 00 DARIN ERSTAD .376 06 ICHIRO SUZUKI 196 94 LARRY WALKER 65 85 WILLIE WILSON 22 54 DON MUELLER .376 58 RICHIE ASHBURN 193 99 ROBIN VENTURA 65 06 GRADY SIZEMORE 22 97 LARRY -

2021 Topps Tier One Checklist .Xls

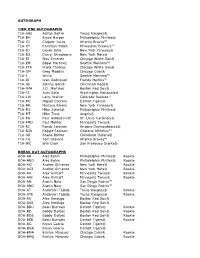

AUTOGRAPH TIER ONE AUTOGRAPHS T1A-ABE Adrian Beltre Texas Rangers® T1A-BH Bryce Harper Philadelphia Phillies® T1A-CJ Chipper Jones Atlanta Braves™ T1A-CY Christian Yelich Milwaukee Brewers™ T1A-DJ Derek Jeter New York Yankees® T1A-DS Darryl Strawberry New York Mets® T1A-EJ Eloy Jimenez Chicago White Sox® T1A-EM Edgar Martinez Seattle Mariners™ T1A-FTA Frank Thomas Chicago White Sox® T1A-GM Greg Maddux Chicago Cubs® T1A-I Ichiro Seattle Mariners™ T1A-IR Ivan Rodriguez Florida Marlins™ T1A-JB Johnny Bench Cincinnati Reds® T1A-JMA J.D. Martinez Boston Red Sox® T1A-JS Juan Soto Washington Nationals® T1A-LW Larry Walker Colorado Rockies™ T1A-MC Miguel Cabrera Detroit Tigers® T1A-MR Mariano Rivera New York Yankees® T1A-MS Mike Schmidt Philadelphia Phillies® T1A-MT Mike Trout Angels® T1A-PG Paul Goldschmidt St. Louis Cardinals® T1A-PMO Paul Molitor Minnesota Twins® T1A-RJ Randy Johnson Arizona Diamondbacks® T1A-RJA Reggie Jackson Oakland Athletics™ T1A-SB Shane Bieber Cleveland Indians® T1A-TG Tom Glavine Atlanta Braves™ T1A-WC Will Clark San Francisco Giants® BREAK OUT AUTOGRAPHS BOA-AB Alec Bohm Philadelphia Phillies® Rookie BOA-ABO Alec Bohm Philadelphia Phillies® Rookie BOA-AG Andres Gimenez New York Mets® Rookie BOA-AGI Andres Gimenez New York Mets® Rookie BOA-AK Alex Kirilloff Minnesota Twins® Rookie BOA-AKI Alex Kirilloff Minnesota Twins® Rookie BOA-AN Austin Nola San Diego Padres™ BOA-ANO Austin Nola San Diego Padres™ BOA-AT Anderson Tejeda Texas Rangers® Rookie BOA-ATE Anderson Tejeda Texas Rangers® Rookie BOA-AV Alex Verdugo Boston -

2011 Topps Gypsy Queen Baseball

Hobby 2011 TOPPS GYPSY QUEEN BASEBALL Base Cards 1 Ichiro Suzuki 49 Honus Wagner 97 Stan Musial 2 Roy Halladay 50 Al Kaline 98 Aroldis Chapman 3 Cole Hamels 51 Alex Rodriguez 99 Ozzie Smith 4 Jackie Robinson 52 Carlos Santana 100 Nolan Ryan 5 Tris Speaker 53 Jimmie Foxx 101 Ricky Nolasco 6 Frank Robinson 54 Frank Thomas 102 David Freese 7 Jim Palmer 55 Evan Longoria 103 Clayton Richard 8 Troy Tulowitzki 56 Mat Latos 104 Jorge Posada 9 Scott Rolen 57 David Ortiz 105 Magglio Ordonez 10 Jason Heyward 58 Dale Murphy 106 Lucas Duda 11 Zack Greinke 59 Duke Snider 107 Chris V. Carter 12 Ryan Howard 60 Rogers Hornsby 108 Ben Revere 13 Joey Votto 61 Robin Yount 109 Fred Lewis 14 Brooks Robinson 62 Red Schoendienst 110 Brian Wilson 15 Matt Kemp 63 Jimmie Foxx 111 Peter Bourjos 16 Chris Carpenter 64 Josh Hamilton 112 Coco Crisp 17 Mark Teixeira 65 Babe Ruth 113 Yuniesky Betancourt 18 Christy Mathewson 66 Madison Bumgarner 114 Brett Wallace 19 Jon Lester 67 Dave Winfield 115 Chris Volstad 20 Andre Dawson 68 Gary Carter 116 Todd Helton 21 David Wright 69 Kevin Youkilis 117 Andrew Romine 22 Barry Larkin 70 Rogers Hornsby 118 Jason Bay 23 Johnny Cueto 71 CC Sabathia 119 Danny Espinosa 24 Chipper Jones 72 Justin Morneau 120 Carlos Zambrano 25 Mel Ott 73 Carl Yastrzemski 121 Jose Bautista 26 Adrian Gonzalez 74 Tom Seaver 122 Chris Coghlan 27 Roy Oswalt 75 Albert Pujols 123 Skip Schumaker 28 Tony Gwynn Sr. 76 Felix Hernandez 124 Jeremy Jeffress 2929 TTyy Cobb 77 HHunterunter PPenceence 121255 JaJakeke PPeavyeavy 30 Hanley Ramirez 78 Ryne Sandberg 126 Dallas -

FROM BULLDOGS to SUN DEVILS the EARLY YEARS ASU BASEBALL 1907-1958 Year ...Record

THE TRADITION CONTINUES ASUBASEBALL 2005 2005 SUN DEVIL BASEBALL 2 There comes a time in a little boy’s life when baseball is introduced to him. Thus begins the long journey for those meant to play the game at a higher level, for those who love the game so much they strive to be a part of its history. Sun Devil Baseball! NCAA NATIONAL CHAMPIONS: 1965, 1967, 1969, 1977, 1981 2005 SUN DEVIL BASEBALL 3 ASU AND THE GOLDEN SPIKES AWARD > For the past 26 years, USA Baseball has honored the top amateur baseball player in the country with the Golden Spikes Award. (See winners box.) The award is presented each year to the player who exhibits exceptional athletic ability and exemplary sportsmanship. Past winners of this prestigious award include current Major League Baseball stars J. D. Drew, Pat Burrell, Jason Varitek, Jason Jennings and Mark Prior. > Arizona State’s Bob Horner won the inaugural award in 1978 after hitting .412 with 20 doubles and 25 RBI. Oddibe McDowell (1984) and Mike Kelly (1991) also won the award. > Dustin Pedroia was named one of five finalists for the 2004 Golden Spikes Award. He became the seventh all-time final- ist from ASU, including Horner (1978), McDowell (1984), Kelly (1990), Kelly (1991), Paul Lo Duca (1993) and Jacob Cruz (1994). ODDIBE MCDOWELL > With three Golden Spikes winners, ASU ranks tied for first with Florida State and Cal State Fullerton as the schools with the most players to have earned college baseball’s top honor. BOB HORNER GOLDEN SPIKES AWARD WINNERS 2004 Jered Weaver Long Beach State 2003 Rickie Weeks Southern 2002 Khalil Greene Clemson 2001 Mark Prior Southern California 2000 Kip Bouknight South Carolina 1999 Jason Jennings Baylor 1998 Pat Burrell Miami 1997 J.D. -

04-30-2015 Angels Game Notes

ANGELS (10-11) @ ATHLETICS (9-13) RHP GARRETT RICHARDS (1-1, 3.75 ERA) vs. RHP JESSE CHAVEZ (0-1, 0.71 ERA) O.Co COLISEUM – 12:37 PM PDT TV – FOX SPORTS WEST RADIO – KLAA AM 830 THURSDAY, APRIL 30, 2015 GAME #22 (10-11) OAKLAND, CA ROAD GAME #12 (6-5) LEADING OFF: Today the Angels play the ‘rubber match’ GAME OF CRON: On Sunday, C.J. Cron’s four hits set a at Oakland and the third game (1-1) of a six-game Bay single-game career-high…He has recorded nine hits in his THIS DATE IN ANGELS HISTORY Area road trip to Oakland (April 28-30; 1-1) and San last 18 at-bats and has three doubles his last seven games. April 30 (2008) A day after Joe Saunders Francisco (May 1-3)…Halos are in a stretch of 25 moves to 5-0, Ervin Santana consecutive days in California (April 20-May 14)…LAA ABOUT FACE: Thru 21 games in 2014, David Freese tallied becomes the third pitcher in club went 4-3 on the seven-game home stand vs. Oakland (2- 13 hits, one double, one home run and six RBI…Thru 21 history to go 5-0 in April…The duo 2) and Texas (2-1)…Following this trip, Angels will host a games in 2015, owns 17 hits, four doubles, four home runs becomes just the second tandem nine-game home stand vs. Seattle (May 4-6), Houston and a team-leading 15 RBI. in MLB history to boast two (May 7-10) and Colorado (May 12-13). -

Padres Press Clips Monday, August 21, 2017

Padres Press Clips Monday, August 21, 2017 Article Source Author Page Padres mailbag: What's to be gained from Hunter Renfroe's UT San Diego Lin 2 demotion? Wild Lamet off the mark in Padres loss UT San Diego Sanders 4 Padres promote Fernando Tatis Jr. to Double-A San Antonio UT San Diego Sanders 6 Dusty Coleman's swing remains a work in progress UT San Diego Sanders 9 Inbox: What's ahead for Padres' rotation? MLB.com Cassavell 11 Padres can't get bats going in finale vs. Nats MLB.com Powers/Ruiz 14 Richard aims to stay on a roll vs. Cardinals MLB.com Powers 17 Fastball command eludes Lamet vs. Nats MLB.com Powers 18 Gonzalez, Nationals beat rookie Lamet, Padres 4-1 Associated Press AP 20 This Day in Padres History, 8/21 FriarWire Center 22 Padres On Deck: De Los Santos, Avila top Padres Players FriarWire Center 23 of the Week Padres On Deck: AAA-El Paso Closes on Playoff Berth FriarWire Center 25 Behind Villanueva, Overton 1 Padres mailbag: What's to be gained from Hunter Renfroe's demotion? Dennis Lin The Padres dropped to 55-69 with Sunday’s loss to the Washington Nationals. Tuesday night, they officially begin a road trip in which they’ll draw at least two problematic matchups. First up are the St. Louis Cardinals and Jedd Gyorko, who torched his former team last season with six homers in seven games. Then it’s on to Miami, where Giancarlo Stanton has been on a Ruthian pace since the All-Star break. -

Sports Authority, Gold Glove Award Winners and Councilmember Cate Inspire Youth to Swing for the Fences

Contact: Rebecca Kelley [email protected] C: (619) 384-5269 Date: February 18, 2016 SPORTS AUTHORITY, GOLD GLOVE AWARD WINNERS AND COUNCILMEMBER CATE INSPIRE YOUTH TO SWING FOR THE FENCES San Diego, CA: To kick off the baseball season, Sports Authority is partnering with Clairemont Hilltoppers Little League and the Toby Wells YMCA for its annual Baseball Field Day Clinics at Cadman Park this Saturday, February 20th, 2016. Beginning at 9:00 a.m., 250 San Diego youth, including twenty (20) Toby Wells YMCA youth, ages eleven through fourteen, will take part in free, educational clinics and exercises focused on key infield, outfield, pitching, hitting and agility fundamentals. “The City of San Diego is honored to recognize Sports Authority with a City of San Diego proclamation for their philanthropic efforts and contributions to expanding America’s Favorite Pastime,” per Councilmember Chris Cate. “I am extremely pleased that Sports Authority chose families in District 6 to be the recipients of donors’ time, talent and treasures.” “Sports Authority is one of the nation’s largest full-line sporting goods retailers dedicated to providing customers with great values and great brands. We have nine locations in San Diego county and promote active, healthy living for all members of the community,” stated Katie Feingold, Sports Authority. “Thanks to the generosity of Sports Authority and its partners, twenty (20) YMCA youth will receive a shopping spree at the Sports Authority on Balboa Avenue,” said Siddhartha Vivek, YMCA of San Diego County. WHAT: Sports Authority Baseball Field Day WHERE: Cadman Park, 4280 Avati Drive, San Diego, CA 92117 WHEN: Saturday, February 20th, 2016 | 9:00 a.m.