Palestinian Schools and Universities in the Occupied West Bank: 1967-2007 Thomas M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CEPS Middle East & Euro-Med Project

CENTRE FOR EUROPEAN POLICY WORKING PAPER NO. 9 STUDIES JUNE 2003 Searching for Solutions THE NEW WALLS AND FENCES: CONSEQUENCES FOR ISRAEL AND PALESTINE GERSHON BASKIN WITH SHARON ROSENBERG This Working Paper is published by the CEPS Middle East and Euro-Med Project. The project addresses issues of policy and strategy of the European Union in relation to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the wider issues of EU relations with the countries of the Barcelona Process and the Arab world. Participants in the project include independent experts from the region and the European Union, as well as a core team at CEPS in Brussels led by Michael Emerson and Nathalie Tocci. Support for the project is gratefully acknowledged from: • Compagnia di San Paolo, Torino • Department for International Development (DFID), London. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed are attributable only to the author in a personal capacity and not to any institution with which he is associated. ISBN 92-9079-436-4 Available for free downloading from the CEPS website (http://www.ceps.be) CEPS Middle East & Euro-Med Project Copyright 2003, CEPS Centre for European Policy Studies Place du Congrès 1 • B-1000 Brussels • Tel: (32.2) 229.39.11 • Fax: (32.2) 219.41.41 e-mail: [email protected] • website: http://www.ceps.be THE NEW WALLS AND FENCES – CONSEQUENCES FOR ISRAEL AND PALESTINE WORKING PAPER NO. 9 OF THE CEPS MIDDLE EAST & EURO-MED PROJECT * GERSHON BASKIN WITH ** SHARON ROSENBERG ABSTRACT ood fences make good neighbours’ wrote the poet Robert Frost. Israel and Palestine are certainly not good neighbours and the question that arises is will a ‘G fence between Israel and Palestine turn them into ‘good neighbours’. -

Sfiff 2019 Program Here

SantaFeIndependent.com 2019 team and advisory board 2019 SFIFF TEAM Jacques Paisner Artistic Director Liesette Paisner Bailey Executive Director Jena Braziel Guest Service Director Derek Horne Director of Shorts Programmer Beau Farrell Associate Programmer Stephanie Love Office Manager Dawn Hoffman Events Manager Deb French Venue Coordinator Chris Bredenberg Tech Director Allie Salazar Graphic Designer Blake Lewis Headquarters Manager Castle Searcy Festival Dailies Adelaide Zhang Box Office Assistant Sarah Mease Box Office Assistant Eileen O’Brien MC Sage Paisner Photographer 2019 SFIFF ADVISORY BOARD Gary Farmer, Chair Chris Eyre Kirk Ellis David Sontag Alexandria Bombach Nicole Guillemet “A young Sundance” Alton Walpole —Indiewire Kimi Ginoza Green Paul Langland Beth Caldarello Xavier Horan “An all inclusive Marissa Juarez resort for cinephiles...” —Filmmaker Magazine “Bringing the community together” 505-349-1414 —Slant Magazine www.santafeindependent.com • [email protected] 418 Montezuma Ave. Suite 22 Santa Fe, NM 87501 3 AD AD welcome WELCOME Dear Santa Fe Independent Film Festival Visitors and Community, Welcome to Santa Fe, and to the festival The Albuquerque Journal calls “The Next Sundance.” The Santa Fe Independent Film Festival (SFIFF), now in its eleventh year, has become one of Santa Fe’s most celebrated annual events. I know you will enjoy SFIFF’s world-class programming and award-winning guests, including renowned ac- tors Jane Seymour and Tantoo Cardinal. I encourage you to investi- gate the many activities, museums, galleries, restaurants, and more that Santa Fe has to offer. The Santa Fe Independent Film Festival fills five days with screen- ings, workshops, educational panels, book signings, and celebra- tions. -

Ashkenaz-Press-Kit-708.Pdf

SYNOPSES (120 WORDS) Ashkenazim—Jews of European origin—are Israel’s “white folks.” And like most white folks in a multicultural society, they see themselves as the social norm and don’t think of themselves in racial or ethnic terms because by now, “aren’t we all Israeli?” Yiddish has been replaced with Hebrew, exile with occupation, the shtetl with the kibbutz and old-fashioned irony with post-modern cynicism. But the paradox of whiteness in Israel is that Ashkenazim aren’t exactly “white folks” historically. A story that begins in the Rhineland and ends in the holy land (or is it the other way around?), Ashkenaz looks at whiteness in Israel and wonders: How did the “Others” of Europe become the “Europe” of the others? (100 WORDS) Ashkenazim—Jews of European origin—are Israel’s “white folks.” And like most white folks in a multicultural society, they see themselves as the social norm and don’t think of themselves in racial or ethnic terms because by now, “aren’t we all Israeli?” Yiddish has been replaced with Hebrew, exile with occupation, the shtetl with the kibbutz and old-fashioned irony with post-modern cynicism. But the paradox of whiteness in Israel is that Ashkenazim aren’t exactly “white folks” historically. Ashkenaz looks at whiteness in Israel and wonders: How did the “Others” of Europe become the “Europe” of the others? (50 WORDS) Ashkenazim—Jews of European origin—are Israel’s “white folks.” But the paradox of whiteness in Israel is that Ashkenazim aren’t exactly “white folks” historically... Ashkenaz looks at whiteness in Israel and wonders: How did the “Others” of Europe become the “Europe” of the others? (25 WORDS) Ashkenaz looks at Ashkenaziness —the Israeli version of whiteness — and wonders: How did the “Others” of Europe become the “Europe” of the others? DIRECTOR’S BIO/FILMOGRAPHY Rachel Leah Jones is a director/producer born in Berkeley, California and raised in Tel Aviv. -

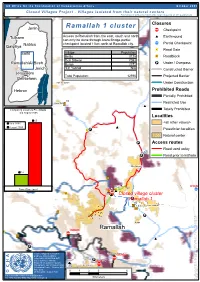

Ramallah 1 Cluster Closures Jenin ‚ Checkpoint

D UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs October 2005 º¹P Closed Villages Project - Villages isolated from their natural centers º¹P Palestinians without permits (the large majority of the population) /" ## Ramallah 1 cluster Closures Jenin ¬Ç Checkpoint ## Tulkarm AccessSalfit to Ramallah from the east, south and north Earthmound can only be done through Atara Bridge partial ¬Ç Nablus checkpoint located 11km north of Ramallah city. Partial Checkpoint Qalqiliya D Road## Gate Salfit Village Population Beitin 3125 /" Roadblock Deir Dibwan 7093 º¹ Ramallah/Al Bireh Burqa 2372 P Under / Overpass 'Ein Yabrud N/A ## Jericho ### Constructed Barrier Jerusalem Total Population: 12590 ## Projected Barrier Bethlehem ## Deir as Sudan Deir as Sudan ## Under Construction ## Hebron Prohibited Roads C /" An Nabi Salih Partially Prohibited ¬Ç ## 15 Umm Safa/" Restricted Use ## # # Comparing situations Pre-Intifada Totally Prohibited and August 2005 Localities 65 Year 2000 <all other values> August 2005 Atara ## D ¬Çº¹P Palestinian localities Natural center º¹P Access routes Road used today 11 12 ##º¹P/" Road prior to Intifada 'Ein'Ein YabrudYabrud 12 /" /" 10 At Tayba /" 9 Beitin Ç Travel Time (min) DCO 2 D ¬ /"Ç## /" ¬/"3 ## 1 Closed village cluster Ramallahº¹P 1 42 /" 43 Deir Dibwan /" /" º¹P the part of the the of part the Burqa Ramallah delimitation the concerning D ¬Ç Beituniya /" ## º¹DP Closure mapping is a work in Qalandiya QalandiyaCamp progress. Closure data is Ç collected by OCHA field staff º¹ ¬ Beit Duqqu and is subject to change. P Atarot 144 Maps will be updated regularly. ### ¬Ç Cartography: OCHA Humanitarian 170 Al Judeira Information Centre - October 2005 Al Jib Beit 'Anan ## Bir Nabala Base data: Al 036Jib 12 O C H A O C H OCHA updateBeit AugustIjza 2005 losedFor comments village contact <[email protected]> cluster # # Tel. -

Deir Dibwan Town Profile

Deir Dibwan Town Profile Prepared by The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem Funded by Spanish Cooperation 2012 Palestinian Localities Study Ramallah Governorate Acknowledgments ARIJ hereby expresses its deep gratitude to the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID) for their funding of this project. ARIJ is grateful to the Palestinian officials in the ministries, municipalities, joint services councils, village committees and councils, and the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) for their assistance and cooperation with the project team members during the data collection process. ARIJ also thanks all the staff who worked throughout the past couple of years towards the accomplishment of this work. 1 Palestinian Localities Study Ramallah Governorate Background This report is part of a series of booklets, which contain compiled information about each city, town, and village in the Ramallah Governorate. These booklets came as a result of a comprehensive study of all localities in Ramallah Governorate, which aims at depicting the overall living conditions in the governorate and presenting developmental plans to assist in developing the livelihood of the population in the area. It was accomplished through the "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment;" the project funded by the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID). The "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment" was designed to study, investigate, analyze and document the socio-economic conditions and the needed programs and activities to mitigate the impact of the current unsecure political, economic and social conditions in Ramallah Governorate. The project's objectives are to survey, analyze, and document the available natural, human, socioeconomic and environmental resources, and the existing limitations and needs assessment for the development of the rural and marginalized areas in Ramallah Governorate. -

500 DUNAM on the MOON a Documentary by RACHEL LEAH JONES 500 DUNAM on the MOON a Documentary by RACHEL LEAH JONES

500 DUNAM ON THE MOON a documentary by RACHEL LEAH JONES 500 DUNAM ON THE MOON a documentary by RACHEL LEAH JONES SYNOPSIS 500 DUNAM ON THE M00N is a documentary about the Palestinian village of Ayn Hawd which was captured and depopulated by Israeli forces in the 1948 war and subsequently transformed into a Jewish artist's colony and renamed Ein Hod. It tells the story of the village's original inhabitants who, after expulsion, settled only 1.5 kilometers away in the outlying hills. Since Israeli law prevents Palestinian refugees from returning to their homes, the refugees of Ayn Hawd established a new village: “Ayn Hawd al-Jadida” (The New Ayn Hawd). Ayn Hawd al-Jadida is an unrecognized village, which means that it receives no services such as electricity, water, or an access road. Relations between the artists and the refugees are complex: unlike most Israelis, the residents of Ein Hod know the Palestinians who lived there before them, since the latter have worked as hired hands for the former. Unlike most Palestinian refugees, the residents of Ayn Hawd al-Jadida know the Israelis who now occupy their homes, the art they produce, and the peculiar ways they try to deal with the fact that their society was created upon the ruins of another. It echoes the story of indigenous peoples everywhere: oppression, resistance, and the struggle to negotiate the scars of the past with the needs of the present and the hopes for the future. Addressing the universal issues of colonization, landlessness, housing rights, gentrification, and cultural appropriation in the specific context of Israel/Palestine, 500 DUNAM ON THE M00N documents the art of dispossession and the creativity of the dispossessed. -

Three Conquests of Canaan

ÅA Wars in the Middle East are almost an every day part of Eero Junkkaala:of Three Canaan Conquests our lives, and undeniably the history of war in this area is very long indeed. This study examines three such wars, all of which were directed against the Land of Canaan. Two campaigns were conducted by Egyptian Pharaohs and one by the Israelites. The question considered being Eero Junkkaala whether or not these wars really took place. This study gives one methodological viewpoint to answer this ques- tion. The author studies the archaeology of all the geo- Three Conquests of Canaan graphical sites mentioned in the lists of Thutmosis III and A Comparative Study of Two Egyptian Military Campaigns and Shishak and compares them with the cities mentioned in Joshua 10-12 in the Light of Recent Archaeological Evidence the Conquest stories in the Book of Joshua. Altogether 116 sites were studied, and the com- parison between the texts and the archaeological results offered a possibility of establishing whether the cities mentioned, in the sources in question, were inhabited, and, furthermore, might have been destroyed during the time of the Pharaohs and the biblical settlement pe- riod. Despite the nature of the two written sources being so very different it was possible to make a comparative study. This study gives a fresh view on the fierce discus- sion concerning the emergence of the Israelites. It also challenges both Egyptological and biblical studies to use the written texts and the archaeological material togeth- er so that they are not so separated from each other, as is often the case. -

FILMS on Palestine-Israel By

PALESTINE-ISRAEL FILMS ON THE HISTORY of the PALESTINE-ISRAEL CONFLICT compiled with brief introduction and commentary by Rosalyn Baxandall A publication of the Palestine-Israel Working Group of Historians Against the War (HAW) December 2014 www.historiansagainstwar.org Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution – NonCommercial – ShareAlike 1 Introduction This compilation of films that relate to the Palestinian-Israeli struggle was made in July 2014. The films are many and the project is ongoing. Why film? Film is often an extraordinarily effective tool. I found that many students in my classes seemed more visually literate than print literate. Whenever I showed a film, they would remember the minute details, characters names and sub-plots. Films were accessible and immediate. Almost the whole class would participate and debates about the film’s meaning were lively. Film showings also improved attendance at teach-ins. At the Truro, Massachusetts, Library in July 2014, the film Voices Across the Divide was shown to the biggest audiences the library has ever had, even though the Wellfleet Library and several churches had refused to allow the film to be shown. Organizing is also important. When a film is controversial, as many in this pamphlet are, a thorough organizing effort including media coverage will augment the turnout for the film. Many Jewish and Palestinian groups list films in their resources. This pamphlet lists them alphabetically, and then by number under themes and categories; the main listings include summaries, to make the films more accessible and easier to use by activist and academic groups. 2 1. 5 Broken Cameras, 2012. -

Traffic, Hazards, and Mobility in the West Bank

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2018 Everyday Occupations: Traffic, Hazards, And Mobility In The esW t Bank Alice Arnold University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Geography Commons Recommended Citation Arnold, A.(2018). Everyday Occupations: Traffic, Hazards, And Mobility In The West Bank. (Master's thesis). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/4676 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EVERYDAY OCCUPATIONS: TRAFFIC, HAZARDS, AND MOBILITY IN THE WEST BANK by Alice Arnold Bachelor of Arts University of Iowa, 2018 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in Geography College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2018 Accepted by: Jessica Barnes, Director of Thesis David Kneas, Reader Amy Mills, Reader Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Alice Arnold, 2018 All Rights Reserved. ii ABSTRACT Mobility in the West Bank is inherently tied to the Israeli military occupation. Each new stage of the decades old conflict comes with new implications for the way Palestinians move around the West Bank. The past years have seen a transition during which the severe mobility restrictions that constituted the closure policy of the second intifada eased and intercity travel has increased. In this study I examine day-to-day experiences of mobility in the West Bank in the post-closure period. -

Annual Report

BETHLEHEM DEVELOPMENT FOUNDATION BDF A Non - Profit Organization ANNUAL REPORT 20181 | BDF Index Board of Trustees Message 5 In Retrospect 2013-2017 6 About BDF 12 Impact of BDF Completed Projects 16 5x5 Playground Doha 16 Al-Salam Children Park-Beit Jala 18 Manger Square Project-Bethlehem 20 Said Khoury Sports Complex-Beit Sahour 22 Bethlehem Solid Waste Management 26 Launching of AFBDF 30 Information 34 Board of Trustees Message Dear Patrons, Trustees, Directors and friends, “The Bethlehem Development Foundation aims to restore I am very pleased to address you our patrons, partners and friends in some peace, love and joy to the people of Bethlehem and the this fifth periodical report. surrounding towns” -BDF Chair Samer Khoury In 2018 BDF concluded its fifth year of operations with a remarkable portfolio of ten vital projects with several others underway. BDF remains dedicated to achieving the foundation’s core vision of regenerating the Bethlehem Governorate Area through the support of our stakeholders from local governance units, religious leadership and Samer S. Khoury Chairman, BoT the region’s vibrant private sector. In this report we highlight the positive impact of BDF-supported projects on the local community: the Restoration of the Church of Nativity, the Manger Square Rehabilitation and Beautification, the Christmas Decorations and Festivities in Manger Square, the Said Khoury Sports Complex and Mini Soccer Playground in Beit Sahour, the Doha Mini Soccer Playground, the Salam Children Park in Beit Jala, the Bethlehem Governorate Solid Waste Management Project, the Rehabilitation of Sanitary Units at the Mosque of Omar in Manger Square and finally the Urban Planning Training of Municipal Engineers. -

An Assessment of Higher Education Needs in the West Bank and Gaza

United States Agency for International Development An Assessment of Higher Education Needs in the West Bank and Gaza Submitted by The Academy for Educational Development Higher Education Support Initiative Strategic Technical Assistance for Results with Training (START) Prepared by Maher Hashweh Mazen Hashweh Sue Berryman September 2003 An Assessment of Higher Education Needs in the West Bank and Gaza Acknowledgments We would like first to extend our greatest gratitude to the Ministry of Education and Higher Education for all the support it gave in the development of this assessment. Special thanks go to Mr. Hisham Kuhail, Assistant Deputy Minister for Higher Education; Dr. Khalil Nakhleh, Head of Commission on Quality Assurance and Accreditation; Dr. Fahoum Shalabi, Director General for Development and Scientific Research/MOHE; and Ms. Frosse Dabiet, Director of International Relations / HE Sector. This work would not have been possible without the cooperation and efforts of the Deans of the Community Colleges and the Universities' Vice-Presidents for Academic Affairs. The Academy for Educational Development (AED) did everything in its capacity to facilitate our work. Special thanks are due here to Elaine Strite, Chief of Party, and Jamileh Abed, Academic Counselor. The important feedback and support of Sue Berryman / World Bank allowed us to better develop the structure, conclusions, and recommendations for this report. Finally, our appreciation and gratitude go to USAID for sponsoring this work. Special thanks go to Ms. Evelyn Levinson, former Higher Education and Training Specialist and Mr. Robert Davidson, Higher Education Team Leader, for their continuous support. Maher Hashweh and Mazen Hashweh Notice The views presented herein are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as reflecting those of the Agency for International Development or the Academy for Educational Development. -

The Role of Palestinian Diaspora Institutions in Mobilizing the International Community

Distr. LIMITED E/ESCWA/SDD/2004/WG.4/CRP.6 20 September 2004 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMISSION FOR WESTERN ASIA Arab-International Forum on Rehabilitation and Development in the Occupied Palestinian Territory: Towards an Independent State Beirut, 11-14 October 2004 THE ROLE OF PALESTINIAN DIASPORA INSTITUTIONS IN MOBILIZING THE INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY By Nadia Hijab ______________________ Note: The references in this document have not been verified. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ESCWA. 04-0456 Advisory Group • Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA) • Palestinian Authority • League of Arab States • United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD)* • United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)* • United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) • Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) • Office of the United Nations Special Coordinator (UNSCO) • United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF)* • United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)* • United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) • International Labour Organization (ILO)* • Al Aqsa Fund/Islamic Development Bank* • World Bank • United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT)* • International Organization for Migration (IOM)* • Arab NGO Network for Development (ANND)* Cosponsors • Friedrich Ebert Foundation • Norwegian People’s Aid • International Development Research Centre (IDRC) • The Norwegian Representative Office to the Palestinian Authority • Qatar Red Crescent • Consolidated Contractors Company • Arabia Insurance Company • Khatib and Alami • Gezairi Transport • El-Nimer Family Foundation _______________________ * These organizations have also contributed as sponsors in financing some of the activities of the Arab International Forum on Rehabilitation and Development in the Occupied Palestinian Territory: Towards an Independent State.