"When Every Town Big Enough to Have a Bank Also Had A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alltime Baseball Champions

ALLTIME BASEBALL CHAMPIONS MAJOR DIVISION Year Champion Head Coach Score Runnerup Site 1914 Orange William Fishback 8 4 Long Beach Poly Occidental College 1915 Hollywood Charles Webster 5 4 Norwalk Harvard Military Academy 1916 Pomona Clint Evans 87 Whittier Pomona HS 1917 San Diego Clarence Price 122 Norwalk Manual Arts HS 1918 San Diego Clarence Price 102 Huntington Park Manual Arts HS 1919 Fullerton L.O. Culp 119 Pasadena Tournament Park, Pasadena 1920 San Diego Ario Schaffer 52 Glendale San Diego HS 1921 San Diego John Perry 145 Los Angeles Lincoln Alhambra HS 1922 Franklin Francis L. Daugherty 10 Pomona Occidental College 1923 San Diego John Perry 121 Covina Fullerton HS 1924 Riverside Ashel Cunningham 63 El Monte Riverside HS 1925 San Bernardino M.P. Renfro 32 Fullerton Fullerton HS 1926 Fullerton 138 Santa Barbara Santa Barbara 1927 Fullerton Stewart Smith 9 0 Alhambra Fullerton HS 1928 San Diego Mike Morrow 30 El Monte El Monte HS 1929 San Diego Mike Morrow 41 Fullerton San Diego HS 1930 San Diego Mike Morrow 80 Cathedral San Diego HS 1931 Colton Norman Frawley 43 Citrus Colton HS 1932 San Diego Mikerow 147 Colton San Diego HS 1933 Santa Maria Kit Carlson 91 San Diego Hoover San Diego HS 1934 Cathedral Myles Regan 63 San Diego Hoover Wrigley Field, Los Angeles 1935 San Diego Mike Morrow 82 Santa Maria San Diego HS 1936 Long Beach Poly Lyle Kinnear 144 Escondido Burcham Field, Long Beach 1937 San Diego Mike Morrow 168 Excelsior San Diego HS 1938 Glendale George Sperry 6 0 Compton Wrigley Field, Los Angeles 1939 San Diego Mike Morrow 30 Long Beach Wilson San Diego HS 1940 Long Beach Wilson Fred Johnson Default (San Diego withdrew) 1941 Santa Barbara Skip W. -

Port Aransas

Inside the Moon Kite Day A2 Island Spring A4 Botanical Gardens A7 Fishing A11 Remember When A16 Issue 829 The 27° 37' 0.5952'' N | 97° 13' 21.4068'' W Island Free The voiceMoon of The Island since 1996 March 5, 2020 Weekly www.islandmoon.com FREE Around Island Grocery Store Waterpark How the Island Voted The Island Going Up! Ride Nueces County Constable By Dale Rankin Precinct 4 (Runoff) Once upon a time on a beach not so Set to open by summer 2020 1123 (45%) Monty Allen far away Spring Breakers swarmed to Comes 1101 (44%) Robert Sherwood the beach north of Packery Channel By Dale Rankin space. Mr. Rasheed said a verbal between Zahn Road and Newport agreement has been reached to locate 269 (10.8%) John Bowers The 20,420 square-foot IGA grocery Pass. Cheek to jowl they lined the a Denny’s diner on a separate three- store under construction on South Down Padre Island totals beach with tents, couches, giant thousand square-foot site fronting Padre Island Drive south of Whitecap bonfires, and bags of trash, most of SPID. 7882 Total Padre Island which got left behind when they went Boulevard will be open by summer Registered Voters home. 2020, according to owners Lori and Mr. Rasheed said the IGA store will Moshin Rasheed. be roughly based on the design of a 2510 (32%) Total Padre Island Police flooded the area but to little Sprouts Farmer’s Market and will voters “We will have the equipment for avail as the revelers, very few of include walk-in coolers for produce the grocery store arriving in the Contested Races Republican which were actual college students, and meat with a butcher on duty, a next few weeks,” Mr. -

Al Brancato This Article Was Written by David E

Al Brancato This article was written by David E. Skelton The fractured skull Philadelphia Athletics shortstop Skeeter Newsome suffered on April 9, 1938 left a gaping hole in the club’s defense. Ten players, including Newsome after he recovered, attempted to fill the void through the 1939 season. One was Al Brancato, a 20- year-old September call-up from Class-A ball who had never played shortstop professionally. Enticed by the youngster’s cannon right arm, Athletics manager Connie Mack moved him from third base to short in 1940. On June 21, after watching Brancato retire Chicago White Sox great Luke Appling on a hard-hit grounder, Mack exclaimed, “There’s no telling how good that boy is going to be.”1 Though no one in the organization expected the diminutive (5-feet-nine and 188 pounds) Philadelphia native’s offense to cause fans to forget former Athletics infield greats Home Run Baker or Eddie Collins, the club was satisfied that Brancato could fill in defensively. “You keep on fielding the way you are and I’ll do the worrying about your hitting,” Mack told Brancato in May 1941.2 Ironically, the youngster’s defensive skills would fail him before the season ended. In September, as the club spiraled to its eighth straight losing season, “baseball’s grand old gentleman” lashed out. “The infielders—[Benny] McCoy, Brancato and [Pete] Suder—are terrible,” Mack grumbled. “They have hit bottom. Suder is so slow it is painful to watch him; Brancato is erratic and McCoy is—oh, he’s just McCoy, that’s all.” 3 After the season ended Brancato enlisted in the US Navy following the country’s entry into the Second World War. -

Texas Baseball History 2018 Fact Book

TEXAS BASEBALL HISTORY LONGHORNS COACHING GREATS W.J. (UNCLE BILLY) DISCH CLIFF GUSTAFSON he late William J. (Uncle Billy) Disch, who coached the s Bibb Falk prepared to retire after the 1967 season, Athletic Texas Longhorns for 29 years (1911-39) and served as Director Darrell Royal set out to find a replacement. Tadvisory coach for a dozen more seasons, guided Texas A When Royal placed his first (and only) call, it was to a baseball teams to 513 victories against only 180 defeats. While San Antonio high school coach by the name of Cliff Gustafson. compiling a career .740 winning percentage, Disch coached 20 Royal called him and said “Hello, this is Darrell Royal.” Southwest Conference championship teams. Gustafson thought to himself, “Oh yeah, well this is Roy His outstanding service to The University, as a person and Rogers.” a coach, has endeared him to the memory of his players and Soon after, Gustafson was named to replace his mentor as others closely connected with Longhorns athletics. Honors that Texas Baseball coach. Twenty-nine years later, Coach Gus was have come to him include induction into the Longhorn Hall of the all-time winningest coach in the history of NCAA Division Honor and election to both the Texas Sports Hall of Fame and I baseball. He guided Texas to 22 Southwest Conference the American Baseball Coaches Association Hall of Fame. (SWC) titles, an NCAA-record 17 College World Series (CWS) While his teams competed in an era when there were no NCAA appearances and two national titles. playoffs, at least six of his teams would have been in strong Along the way he produced countless professional baseball contention had such a prize been awarded. -

Baseball Coaching Records

BASEBALL COACHING RECORDS All-Divisions Coaching Records 2 Division I Coaching Records 4 Division II Coaching Records 7 Division III Coaching Records 10 ALL-DIVISIONS COACHING RECORDS In statistical rankings, the rounding of percentages and/or averages may Coach, Team(s) Years Won Lost Tied Pct. indicate ties where none exists. In these cases, the numerical order of the 41. *John Vodenlich, Edgewood 1998- 19 606 226 1 .728 rankings is accurate. Ties counted as half won, half lost. 99, Wis.-Whitewater 2004-20 42. Bill Holowaty, Eastern Conn. St. 45 1,412 528 7 .727 1969-13 WINNINGEST COACHES ALL-TIME 43. Loyal Park, Harvard 1969-78 10 247 93 0 .726 44. Judson Hyames, Western Mich. 15 166 62 2 .726 1922-36 Top 50 By Percentage 45. *Tim Scannell, Trinity (TX) 1999-20 22 709 268 0 .726 (Minimum 10 years as a head coach at an NCAA school; 46. John Flynn, Providence 1924-25, 10 147 55 2 .725 includes all victories as coach at a four-year institution.) 27-34 Coach, Team(s) Years Won Lost Tied Pct. 47. Skip Bertman, LSU 1984-01 18 870 330 3 .724 48. Gene Stephenson, Wichita St. 36 1,768 675 3 .723 1. Robert Henry Lee, Southern U. 12 172 35 0 .831 1978-13 1949-60 49. Carl Lundgren, Michigan 1914-16, 20 302 111 20 .721 2. Don Schaly, Marietta 1964-03 40 1,438 329 13 .812 18-20, Illinois 21-34 3. John Barry, Holy Cross 1921-60 40 619 146 5 .807 50. -

April 2021 Auction Prices Realized

APRIL 2021 AUCTION PRICES REALIZED Lot # Name 1933-36 Zeenut PCL Joe DeMaggio (DiMaggio)(Batting) with Coupon PSA 5 EX 1 Final Price: Pass 1951 Bowman #305 Willie Mays PSA 8 NM/MT 2 Final Price: $209,225.46 1951 Bowman #1 Whitey Ford PSA 8 NM/MT 3 Final Price: $15,500.46 1951 Bowman Near Complete Set (318/324) All PSA 8 or Better #10 on PSA Set Registry 4 Final Price: $48,140.97 1952 Topps #333 Pee Wee Reese PSA 9 MINT 5 Final Price: $62,882.52 1952 Topps #311 Mickey Mantle PSA 2 GOOD 6 Final Price: $66,027.63 1953 Topps #82 Mickey Mantle PSA 7 NM 7 Final Price: $24,080.94 1954 Topps #128 Hank Aaron PSA 8 NM-MT 8 Final Price: $62,455.71 1959 Topps #514 Bob Gibson PSA 9 MINT 9 Final Price: $36,761.01 1969 Topps #260 Reggie Jackson PSA 9 MINT 10 Final Price: $66,027.63 1972 Topps #79 Red Sox Rookies Garman/Cooper/Fisk PSA 10 GEM MT 11 Final Price: $24,670.11 1968 Topps Baseball Full Unopened Wax Box Series 1 BBCE 12 Final Price: $96,732.12 1975 Topps Baseball Full Unopened Rack Box with Brett/Yount RCs and Many Stars Showing BBCE 13 Final Price: $104,882.10 1957 Topps #138 John Unitas PSA 8.5 NM-MT+ 14 Final Price: $38,273.91 1965 Topps #122 Joe Namath PSA 8 NM-MT 15 Final Price: $52,985.94 16 1981 Topps #216 Joe Montana PSA 10 GEM MINT Final Price: $70,418.73 2000 Bowman Chrome #236 Tom Brady PSA 10 GEM MINT 17 Final Price: $17,676.33 WITHDRAWN 18 Final Price: W/D 1986 Fleer #57 Michael Jordan PSA 10 GEM MINT 19 Final Price: $421,428.75 1980 Topps Bird / Erving / Johnson PSA 9 MINT 20 Final Price: $43,195.14 1986-87 Fleer #57 Michael Jordan -

The Baseball Film in Postwar America ALSO by RON BRILEY and from MCFARLAND

The Baseball Film in Postwar America ALSO BY RON BRILEY AND FROM MCFARLAND The Politics of Baseball: Essays on the Pastime and Power at Home and Abroad (2010) Class at Bat, Gender on Deck and Race in the Hole: A Line-up of Essays on Twentieth Century Culture and America’s Game (2003) The Baseball Film in Postwar America A Critical Study, 1948–1962 RON BRILEY McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London All photographs provided by Photofest. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Briley, Ron, 1949– The baseball film in postwar America : a critical study, 1948– 1962 / Ron Briley. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7864-6123-3 softcover : 50# alkaline paper 1. Baseball films—United States—History and criticism. I. Title. PN1995.9.B28B75 2011 791.43'6579—dc22 2011004853 BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE © 2011 Ron Briley. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. On the cover: center Jackie Robinson in The Jackie Robinson Story, 1950 (Photofest) Manufactured in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com Table of Contents Preface 1 Introduction: The Post-World War II Consensus and the Baseball Film Genre 9 1. The Babe Ruth Story (1948) and the Myth of American Innocence 17 2. Taming Rosie the Riveter: Take Me Out to the Ball Game (1949) 33 3. -

Want and Bait 11 27 2020.Xlsx

Year Maker Set # Var Beckett Name Upgrade High 1967 Topps Base/Regular 128 a $ 50.00 Ed Spiezio (most of "SPIE" missing at top) 1967 Topps Base/Regular 149 a $ 20.00 Joe Moeller (white streak btwn "M" & cap) 1967 Topps Base/Regular 252 a $ 40.00 Bob Bolin (white streak btwn Bob & Bolin) 1967 Topps Base/Regular 374 a $ 20.00 Mel Queen ERR (underscore after totals is missing) 1967 Topps Base/Regular 402 a $ 20.00 Jackson/Wilson ERR (incomplete stat line) 1967 Topps Base/Regular 427 a $ 20.00 Ruben Gomez ERR (incomplete stat line) 1967 Topps Base/Regular 447 a $ 4.00 Bo Belinsky ERR (incomplete stat line) 1968 Topps Base/Regular 400 b $ 800 Mike McCormick White Team Name 1969 Topps Base/Regular 47 c $ 25.00 Paul Popovich ("C" on helmet) 1969 Topps Base/Regular 440 b $ 100 Willie McCovey White Letters 1969 Topps Base/Regular 447 b $ 25.00 Ralph Houk MG White Letters 1969 Topps Base/Regular 451 b $ 25.00 Rich Rollins White Letters 1969 Topps Base/Regular 511 b $ 25.00 Diego Segui White Letters 1971 Topps Base/Regular 265 c $ 2.00 Jim Northrup (DARK black blob near right hand) 1971 Topps Base/Regular 619 c $ 6.00 Checklist 6 644-752 (cprt on back, wave on brim) 1973 Topps Base/Regular 338 $ 3.00 Checklist 265-396 1973 Topps Base/Regular 588 $ 20.00 Checklist 529-660 upgrd exmt+ 1974 Topps Base/Regular 263 $ 3.00 Checklist 133-264 upgrd exmt+ 1974 Topps Base/Regular 273 $ 3.00 Checklist 265-396 upgrd exmt+ 1956 Topps Pins 1 $ 500 Chuck Diering SP 1956 Topps Pins 2 $ 30.00 Willie Miranda 1956 Topps Pins 3 $ 30.00 Hal Smith 1956 Topps Pins 4 $ -

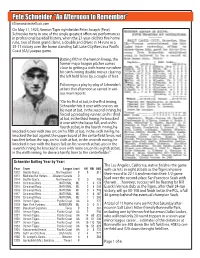

Pete Schneider

Pete Schneider, “An Afternoon to Remember” ©DiamondsintheDusk.com On May 11, 1923, Vernon Tiger rightfielder Peter Joseph (Pete) Schneider turns in one of the single greatest offensive performances in professional baseball history, when the 27-year-old hits five home runs, two of them grand slams, a double and drives in 14 runs in a 35-11 victory over the home standing Salt Lake City Bees in a Pacific Coast (AA) League game. Batting fifth in the Vernon lineup, the former major league pitcher comes close to getting a sixth home run when his sixth-inning double misses clearing the left field fence by a couple of feet. Following is a play-by-play of Schneider’s at bats that afternoon as carried in vari- ous news reports: “On his first at bat, in the first inning, Schneider hits it over with one on; on his next at bat, in the second inning, he forced a preceding runner; on his third at bat, in the third Inning, he knocked it over with the bases full; and on his fourth at bat, in the fourth inning, he knocked it over with two on; on his fifth at bat, in the sixth inning, he knocked the ball against the upper board of the centerfield fence, not two feet below the top; on his sixth at bat, in the seventh inning, he knocked it over with the bases full; on his seventh at bat, also in the seventh inning, he knocked it over with none on; on his eighth at bat, in the ninth inning, he drove a terrific liner to the centerfielder.” Schneider Batting Year by Year: The Los Angeles, California, native finishes the game Year Team League Level HR RBI AVG with six hits in eight at bats as the Tigers improve 1912 Seattle Giants ..................... -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

Minor League Presidents

MINOR LEAGUE PRESIDENTS compiled by Tony Baseballs www.minorleaguebaseballs.com This document deals only with professional minor leagues (both independent and those affiliated with Major League Baseball) since the foundation of the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues (popularly known as Minor League Baseball, or MiLB) in 1902. Collegiate Summer leagues, semi-pro leagues, and all other non-professional leagues are excluded, but encouraged! The information herein was compiled from several sources including the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (2nd Ed.), Baseball Reference.com, Wikipedia, official league websites (most of which can be found under the umbrella of milb.com), and a great source for defunct leagues, Indy League Graveyard. I have no copyright on anything here, it's all public information, but it's never all been in one place before, in this layout. Copyrights belong to their respective owners, including but not limited to MLB, MiLB, and the independent leagues. The first section will list active leagues. Some have historical predecessors that will be found in the next section. LEAGUE ASSOCIATIONS The modern minor league system traces its roots to the formation of the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues (NAPBL) in 1902, an umbrella organization that established league classifications and a salary structure in an agreement with Major League Baseball. The group simplified the name to “Minor League Baseball” in 1999. MINOR LEAGUE BASEBALL Patrick Powers, 1901 – 1909 Michael Sexton, 1910 – 1932 -

College Baseball Foundation January 30, 2008 Boyd, Thank You For

College Baseball Foundation P.O. Box 6507 Phone: 806-742-0301 x249 Lubbock TX 79493-6507 E-mail: [email protected] January 30, 2008 Boyd, Thank you for participating in the balloting for the College Baseball Hall of Fame’s 2008 Induction Class. We appreciate your willingness to help. In the voters packet you will find the official ballot, an example ballot, and the nominee biographies: 1. The official ballot is what you return to us. Please return to us no later than Mon- day, February 11. 2. The example ballot’s purpose is to demonstrate the balloting rules. Obviously the names on the example ballot are not the nominee names. That was done to prevent you from being biased by the rankings you see there. 3. Each nominee has a profile in the biography packet. Some are more detailed than others and reflect what we received from the institutions and/or obtained in our own research. The ballot instructions are somewhat detailed, so be sure to read the directions at the top of the official ballot. Use the example ballot as a reference. Please try to consider the nominees based on their collegiate careers. In many cases nominees have gone on to professional careers but keep the focus on his college career as a player and/or coach. The Veterans (pre-1947) nominees often lack biographical details relative to those in the post-1947 categories. In those cases, the criteria may take on a broader spectrum to include the impact they had on the game/history of college baseball, etc.