The Thatcher Experiment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Employment and Unemployment in the First Half of 1981

Employment and unemployment in the first half of 1981 Employment displayed sluggish growth as auto manufacturing failed to keep pace with other industries and homebuilding remained depressed; unemployment held close to the late 1980 levels DIANE N. WESTCOTT models before the Labor market signals became mixed as 1981 unfolded . rebuilding of inventories of 1981 During the first half of the year, total employment con- close of the model year. It is questionable, though, . auto sales will be tinued to show some signs of improvement from the re- whether this increase in U.S high and the cessionary declines of 1980. However, unemployment sustained; the cost of borrowing remains was reasonably stable, with the overall jobless rate at manufacturers' rebate program has ended. depressed in the first 7 .4 percent in each of the first two quarters of 1981, not The housing industry remained consistently high, and much different from the 7.5-percent rate in the last half half. Mortgage interest rates were lending institutions to of 1980. Although both the household and payroll em- the new forms of financing by reassure buy- ployment series' were moving upward, the pace of the make borrowing more feasible did little to interest rates have payroll series slowed to almost a trickle by the end of ers and home builders . Although only the housing in- the second quarter. climbed to new heights, thus far, Employment in 1980 had been curtailed largely as a dustry seems to have suffered unduly. result of job losses in manufacturing and construction Homebuilding, auto manufacturing still struggling -particularly in two key industries, automobile manu- nonfarm payroll employ- facturing and housing construction . -

The Effect of Generics on the Food Market Structure Robert L

Perspectives The Effect of Generics on the Food Market Structure Robert L. Wills and Rosanna L. Mentzer (202) 447-6363 enerics-products in plain packages tion of those products were shipped directly whose stark labels read "GRAPE to stores by manufacturers. GJELLY,'' ''PAPER TOWELS,'' or The USDA analysis compared several "SHORTENING"-have steadily grown characteristics for three groups of product in number on supermarket shelves since be categories: the total sample which contained ing introduced to U.S. consumers in 1977. 384 categories, the 128 product categories Sales of generic products have expanded that had generics in April/May 1979, and while breaking all the rules of successful the product categories that offered generics branded food marketing: extensive adver a year later. This last group contains 54 tising, enticing packaging, and a manufac product categories in addition to those turer's or retailer's logo. categories with generics in 1979. The prod How have generics done it? Their appeal ucts included in this analysis were packaged is price. Generic products are usually priced processed foods because information on 15 to 40 percent below the private label labeling of freshmeats and produce was not (store brand) and branded competition. available. The phenomenal success of these no-frills While around 50 percent of stores carried alternatives has shaken up their product some generic item in 1980, any particular markets. generic item on average was carried by only 8.1 percent of the stores in that year. This Growth of Generics percent of stores expanded between 1979 U.S. food stores responded quickly to the and 1980 for each group presented in table introduction of generics. -

Median and Average Sales Prices of New Homes Sold in United States

Median and Average Sales Prices of New Homes Sold in United States Period Median Average Jan 1963 $17,200 (NA) Feb 1963 $17,700 (NA) Mar 1963 $18,200 (NA) Apr 1963 $18,200 (NA) May 1963 $17,500 (NA) Jun 1963 $18,000 (NA) Jul 1963 $18,400 (NA) Aug 1963 $17,800 (NA) Sep 1963 $17,900 (NA) Oct 1963 $17,600 (NA) Nov 1963 $18,400 (NA) Dec 1963 $18,700 (NA) Jan 1964 $17,800 (NA) Feb 1964 $18,000 (NA) Mar 1964 $19,000 (NA) Apr 1964 $18,800 (NA) May 1964 $19,300 (NA) Jun 1964 $18,800 (NA) Jul 1964 $19,100 (NA) Aug 1964 $18,900 (NA) Sep 1964 $18,900 (NA) Oct 1964 $18,900 (NA) Nov 1964 $19,300 (NA) Dec 1964 $21,000 (NA) Jan 1965 $20,700 (NA) Feb 1965 $20,400 (NA) Mar 1965 $19,800 (NA) Apr 1965 $19,900 (NA) May 1965 $19,600 (NA) Jun 1965 $19,800 (NA) Jul 1965 $21,000 (NA) Aug 1965 $20,200 (NA) Sep 1965 $19,600 (NA) Oct 1965 $19,900 (NA) Nov 1965 $20,600 (NA) Dec 1965 $20,300 (NA) Jan 1966 $21,200 (NA) Feb 1966 $20,900 (NA) Mar 1966 $20,800 (NA) Apr 1966 $23,000 (NA) May 1966 $22,300 (NA) Jun 1966 $21,200 (NA) Jul 1966 $21,800 (NA) Aug 1966 $20,700 (NA) Sep 1966 $22,200 (NA) Oct 1966 $20,800 (NA) Nov 1966 $21,700 (NA) Dec 1966 $21,700 (NA) Jan 1967 $22,200 (NA) Page 1 of 13 Median and Average Sales Prices of New Homes Sold in United States Period Median Average Feb 1967 $22,400 (NA) Mar 1967 $22,400 (NA) Apr 1967 $22,300 (NA) May 1967 $23,700 (NA) Jun 1967 $23,900 (NA) Jul 1967 $23,300 (NA) Aug 1967 $21,700 (NA) Sep 1967 $22,800 (NA) Oct 1967 $22,300 (NA) Nov 1967 $23,100 (NA) Dec 1967 $22,200 (NA) Jan 1968 $23,400 (NA) Feb 1968 $23,500 (NA) Mar 1968 -

The California Supreme Court Survey - a Review of Decisions: June 1981-August 1981

Pepperdine Law Review Volume 9 Issue 3 Article 6 4-15-1982 The California Supreme Court Survey - A Review of Decisions: June 1981-August 1981 Craig H. Millet Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/plr Part of the Courts Commons Recommended Citation Craig H. Millet The California Supreme Court Survey - A Review of Decisions: June 1981-August 1981, 9 Pepp. L. Rev. Iss. 3 (1982) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/plr/vol9/iss3/6 This Survey is brought to you for free and open access by the Caruso School of Law at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pepperdine Law Review by an authorized editor of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. The California Supreme Court Survey A Review of Decisions: June 1981-August 1981 In a continuing effort to provide the legal community with an analytical examina- tion of recent CaliforniaSupreme Court cases, the PepperdineLaw Review surveys the following decisions as indicative of currentcourt activity. The following is des- ignated to briefly expose the practitionerto recent decisions which are anticipated to significantly impact California law. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. CONSTITUTIONAL LAW A. CRIMINAL PROCEDURE 1. Specific Performance as a Remedy for Broken Plea Agreements: People v. Calloway ........... 680 2. Expanding Pre-TrialDiscovery: Holman v. Superior Court .................................... 698 3. Excessive Pre-TrialPublicity as it Affects the Right to a FairTrial: Martinez v. Superior Court ............................................. 700 4. Inquiry into the Use of Peremptory Challenges: People v. W illiams ............................... -

The Pound Sterling

ESSAYS IN INTERNATIONAL FINANCE No. 13, February 1952 THE POUND STERLING ROY F. HARROD INTERNATIONAL FINANCE SECTION DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL INSTITUTIONS PRINCETON UNIVERSITY Princeton, New Jersey The present essay is the thirteenth in the series ESSAYS IN INTERNATIONAL FINANCE published by the International Finance Section of the Department of Economics and Social Institutions in Princeton University. The author, R. F. Harrod, is joint editor of the ECONOMIC JOURNAL, Lecturer in economics at Christ Church, Oxford, Fellow of the British Academy, and• Member of the Council of the Royal Economic So- ciety. He served in the Prime Minister's Office dur- ing most of World War II and from 1947 to 1950 was a member of the United Nations Sub-Committee on Employment and Economic Stability. While the Section sponsors the essays in this series, it takes no further responsibility for the opinions therein expressed. The writer's are free to develop their topics as they will and their ideas may or may - • v not be shared by the editorial committee of the Sec- tion or the members of the Department. The Section welcomes the submission of manu- scripts for this series and will assume responsibility for a careful reading of them and for returning to the authors those found unacceptable for publication. GARDNER PATTERSON, Director International Finance Section THE POUND STERLING ROY F. HARROD Christ Church, Oxford I. PRESUPPOSITIONS OF EARLY POLICY S' TERLING was at its heyday before 1914. It was. something ' more than the British currency; it was universally accepted as the most satisfactory medium for international transactions and might be regarded as a world currency, even indeed as the world cur- rency: Its special position waS,no doubt connected with the widespread ramifications of Britain's foreign trade and investment. -

A Contrasting Study of the Rainfall Anomalies Between Central Tibet and Central India During the Summer Monsoon Season of 1979

A Contrasting Study of the Rainfall Anomalies between Central Tibet and Central C. C. Chang1 India during the Summer Institute of Atmospheric Physics Monsoon Season of 1979 Academia Sinica, Beijing Abstract ratio thus computed is classified into four categories: Based on a comparison of rainfall anomalies between central India Weak monsoon day (W): 0 < r < 0.5 and central Tibet in July and August 1979, a negative correlation be- Normal monsoon day (N): 0.5 < r < 1.5 tween them is found. When an active monsoon prevailed over cen- Strong monsoon day (S): 1.5 < r < 4.0 tral India, a break monsoon occurred over central Tibet, and vice versa. The large-scale circulation conditions for an active Indian Vigorous monsoon day (V): r > 4.0 monsoon are characterized by the presence of a large area of nega- tive height departures over the Indian Peninsula and large areas of Thus, we have a uniform and consistent standard of classi- positive height departures over central Tibet. On the other hand, the fication for the monsoon rainfalls on both sides of the circulation conditions responsible for a break monsoon in India Himalayas. are characterized by frequent wave-trough activity over Tibet and the regions to the west of Tibet, and by a dominating high-pressure area over the Indian Peninsula. 2. Comparison of the rainfall anomalies between cen- tral India and central Tibet 1. Methods of analysis Figure 1 shows time series of the rainfall ratio of central India The rainfall data were taken from the Indian Daily Weather (r7) and central Tibet (rc) for July and August 1979. -

List of Technical Papers

Program Reports Report Title Copies Number Number 1: Program Prospectus. December 1963. 2 Program Design Report. February 1965. 2 Number 2: Supplement: 1968-1969 Work Program. February 1968. 1 Supplement: 1969-1970 Work Program. May 1969. 0 Number 3: Cost Accounting Manual. February 1965. 1 Number 4: Organizational Manual. February 1965. 2 Guide Plan: Central Offices for the Executive Branch of State Number 5: 2 Government. April1966. XIOX Users Manual for the IBM 7090/7094 Computer. November Number 6: 2 1966. Population Projections for the State of Rhode Island and its Number 7: 2 Municipalities--1970-2000. December 1966. Plan for Recreation, Conservation, and Open Space (Interim Report). Number 8: 2 February 1968. Rhode Island Transit Plan: Future Mass Transit Services and Number 9: 2 Facilities. June 1969. Plan for the Development and Use of Public Water Supplies. Number 10: 1 September 1969. Number 11: Plan for Public Sewerage Facility Development. September 1969. 2 Plan for Recreation, Conservation, and Open Space (Second Interim Number 12: 2 Report). May 1970. Number 13: Historic Preservation Plan. September 1970. 2 Number 14: Plan for Recreation, Conservation, and Open Space. January 1971. 2 Number 15: A Department of Transportation for Rhode Island. March 1971. 2 State Airport System Plan (1970-1990). Revised Summary Report. Number 16: 2 December 1974. Number 17: Westerly Economic Growth Center, Planning Study. February 1973. 1 Plan for Recreation, Conservation, and Open Space--Supplement. June Number 18: 2 1973. Number 19: Rhode Island Transportation Plan--1990. January 1975. 2 Number 20: Solid Waste Management Plan. December 1973. 2 1 Number 21: Report of the Trail Advisory Committee. -

Tax Features Volume 25 Number 7 August 1981

MONTHLY TAX FEATURES Toward bolte r government Volume 25, Number 7, August 198 1 Founde d 1937 Tax Foundation, Incorporated 1875 Connecticut Avenue, N .W. q Washington, D.C. 20009 q 202-328-4500 q New "Facts & First Quarter Tax Index Tops 400 Figures" Gives Fiscal Profile of American As Size of Federal Tax Bite Climbs Economy The Tax Index passed anothe r In the first quarter of this year, th e "To find the right answer, it is firs t milestone in the first quarter of 1981 , Federal Tax Index reached 412 .2, up necessary to ask the right question, " topping the 400 mark (1967 = 100) from the previous quarter by 8 .3 per- observes Tax Foundation's Chairma n for the first time, according to Tax cent, or an annual rate of 37 .6 per- Thomas M. Macioce in his Foreword Foundation economists . The Index cent. At the same time, the State - to Facts and Figures on Government rose by 6 .8 percent from the fourt h Local Index rose by 3 .8 percent, or Finance, 21st biennial edition . He quarter of 1980 for a stunning 30 . 3 16.3 percent on an annual-rate basis , continues by pointing out that "in percent annual rate of increase. At a reaching 400.0 . matters of public finance and in the level of 408.2 in this year's firs t The major taxes contributing to th e tax and fiscal arena, those question s quarter, the Tax Index was almost 1 6 latest quarterly upsurge in the Index cannot be formulated without moun - percent higher than in the same pe- were Federal social security taxes tains of statistical data . -

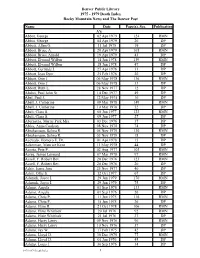

1979 Death Index Rocky Mountain News and the Denver Post Name Date Page(S), Sec

Denver Public Library 1975 - 1979 Death Index Rocky Mountain News and The Denver Post Name Date Page(s), Sec. Publication A's Abbot, George 02 Apr 1979 124 RMN Abbot, George 04 Apr 1979 26 DP Abbott, Allen G. 11 Jul 1975 19 DP Abbott, Bruce A. 20 Apr 1979 165 RMN Abbott, Bruce Arnold 19 Apr 1979 43 DP Abbott, Elwood Wilbur 14 Jun 1978 139 RMN Abbott, Elwood Wilbur 18 Jun 1978 47 DP Abbott, Gertrude J. 27 Apr 1976 31 DP Abbott, Jean Dyer 25 Feb 1976 20 DP Abbott, Orin J. 06 May 1978 136 RMN Abbott, Orin J. 06 May 1978 33 DP Abbott, Ruth L. 28 Nov 1977 12 DP Abdoo, Paul John Sr. 14 Dec 1977 49 DP Abel, Paul J. 12 May 1975 16 DP Abell, J. Catherine 09 Mar 1978 149 RMN Abell, J. Catherine 10 Mar 1978 52 DP Abelt, Clara S. 08 Jun 1977 123 RMN Abelt, Clara S. 09 Jun 1977 27 DP Abernatha, Martie Park Mrs. 03 Dec 1976 37 DP Ables, Anna Coulson 08 Nov 1978 74 DP Abrahamson, Selma R. 05 Nov 1979 130 RMN Abrahamson, Selma R. 05 Nov 1979 18 DP Acevedo, Homero E. Dr. 01 Apr 1978 15 DP Ackerman, Maurice Kent 11 May 1978 44 DP Acosta, Pete P. 02 Aug 1977 103 RMN Acree, Jessee Leonard 07 Mar 1978 97 RMN Acsell, F. Robert Rev. 20 Dec 1976 123 RMN Acsell, F. Robert Rev. 20 Dec 1976 20 DP Adair, Jense Jane 25 Nov 1977 40 DP Adair, Ollie S. -

Wo 2013/072763 A3 ©

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2013/072763 A3 23 May 2013 (23.05.2013) W P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, A61K 31/4164 (2006.01) A61P 25/00 (2006.01) HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, A61K 9/70 (2006.01) KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, (21) International Application Number: NO, NZ, OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, PCT/IB20 12/002797 RW, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, (22) International Filing Date: TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, 16 November 2012 (16.1 1.2012) ZM, ZW. (25) Filing Language: English (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, (26) Publication Language: English GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, (30) Priority Data: UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, TJ, 61/560,577 16 November 201 1 (16. 11.201 1) US TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, DK, EE, ES, FI, FR, GB, GR, HR, HU, IE, IS, IT, LT, LU, LV, (71) Applicant: NOMETICS INC. [CA/CA]; Parteq, 1625 MC, MK, MT, NL, NO, PL, PT, RO, RS, SE, SI, SK, SM, Biosciences Complex, Queen's University, Queen's Univer TR), OAPI (BF, BJ, CF, CG, CI, CM, GA, GN, GQ, GW, sity Biosciences Complex, Kingston, ON K7L 3N6 (CA). -

A SCOTTISH CURRENCY? 5 Lessons from the Design Flaws of Pound Sterling 2 | a SCOTTISH CURRENCY? CONTENTS

A SCOTTISH CURRENCY? 5 Lessons from the Design Flaws of Pound Sterling 2 | A SCOTTISH CURRENCY? CONTENTS A Scottish Currency? 3 The design flaws of the pound: 4 1. The amount of money in the economy depends on the confidence of bankers 4 2. Any attempt to reduce household debt can lead to a recession 5 3. The economy can only be stimulated through encouraging further indebtedness 6 4. The proceeds from the creation of money are captured by the banking sector rather than benefiting taxpayers 7 5. Banks cannot be allowed to fail, because if they did, the payments system would collapse 8 Conclusion 9 More information 10 5 LESSONS FROM THE DESIGN FLAWS OF POUND STERLING | 3 A SCOTTISH CURRENCY? In September 2014, Scotland will hold a referendum to decide whether to separate from the UK. A major question concerns which currency an independent Scotland would use: the pound, the euro, or a new Scottish currency? The Scottish government has stated that it will keep the pound sterling following a successful Yes vote for independence1. But an independent Scotland, making up just 8.5% of a pound sterling monetary union, would have no sway over monetary policy set by the Bank of England. Meanwhile the governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney, and senior government ministers have been vocal about the challenges of an independent Scotland using the pound. For this reason, an independent Scotland may have to abandon the pound and establish its own currency, to regain control over its own monetary policy and economic affairs. -

Black Wednesday’

Salmond currency plan threatens a Scottish ‘Black Wednesday’ Alex Salmond has five plans for the currency of an independent Scotland according to his list in the STV debate on 25th August (and then there is the latent plan F). They were presented as a range of equally attractive options. This makes light of the issue. One of the options – using “a currency like the Danish krone” - means entering the ERM (the Exchange Rate Mechanism) that the UK was so disastrously a part of and which the UK wasted a meaningful portion of its foreign exchange reserves (£48 billion in today’s money) trying to stay within just on 16th September 1992. That was Black Wednesday, when the Bank of England base rate went up to 15%. Notably Alex Salmond omitted to mention the Norwegian krone: Scotland, with high public spending, too little oil&gas left in the North Sea, and an all-in national debt of £131 billion equivalent on a GDP of £146 billion, will need its oil&gas tax revenues to either defend its currency or manage its debt, and will not have enough left over for a Sovereign Wealth Fund. Scotland has the attributes of a lax fiscal policy now: a current deficit of taxes versus spending (called a primary fiscal deficit) of 5% of GDP, with extra spending promised by the SNP that could expand an already high debt as a proportion of GDP. The debt is likely to start out at above 70% in cash, plus another 20% in contingent liabilities like PFI, backing for Bank of Scotland and RBS, and Scotland’s share of the Euro bailout of Ireland and Portugal.