Global Abundance Estimates for 9,700 Bird Species

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dung Beetle Richness, Abundance, and Biomass Meghan Gabrielle Radtke Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2006 Tropical Pyramids: Dung Beetle Richness, Abundance, and Biomass Meghan Gabrielle Radtke Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Recommended Citation Radtke, Meghan Gabrielle, "Tropical Pyramids: Dung Beetle Richness, Abundance, and Biomass" (2006). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 364. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/364 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. TROPICAL PYRAMIDS: DUNG BEETLE RICHNESS, ABUNDANCE, AND BIOMASS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Biological Sciences by Meghan Gabrielle Radtke B.S., Arizona State University, 2001 May 2007 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. G. Bruce Williamson, and my committee members, Dr. Chris Carlton, Dr. Jay Geaghan, Dr. Kyle Harms, and Dr. Dorothy Prowell for their help and guidance in my research project. Dr. Claudio Ruy opened his laboratory to me during my stay in Brazil and collaborated with me on my project. Thanks go to my field assistants, Joshua Dyke, Christena Gazave, Jeremy Gerald, Gabriela Lopez, and Fernando Pinto, and to Alejandro Lopera for assisting me with Ecuadorian specimen identifications. I am grateful to Victoria Mosely-Bayless and the Louisiana State Arthropod Museum for allowing me work space and access to specimens. -

The Solomon Islands

THE SOLOMON ISLANDS 14 SEPTEMBER – 7 OCTOBER 2007 TOUR REPORT LEADER: MARK VAN BEIRS Rain, mud, sweat, steep mountains, shy, skulky birds, shaky logistics and an airline with a dubious reputation, that is what the Solomon Islands tour is all about, but these forgotten islands in the southwest Pacific also hold some very rarely observed birds that very few birders will ever have the privilege to add to their lifelist. Birdquest’s fourth tour to the Solomons went without a hiccup. Solomon Airlines did a great job and never let us down, it rained regularly and we cursed quite a bit on the steep mountain trails, but the birds were out of this world. We birded the islands of Guadalcanal, Rennell, Gizo and Malaita by road, cruised into Ranongga and Vella Lavella by boat, and trekked up into the mountains of Kolombangara, Makira and Santa Isabel. The bird of the tour was the incredible and truly bizarre Solomon Islands Frogmouth that posed so very, very well for us. The fantastic series of endemics ranged from Solomon Sea Eagles, through the many pigeons and doves - including scope views of the very rare Yellow-legged Pigeon and the bizarre Crested Cuckoo- Dove - and parrots, from cockatoos to pygmy parrots, to a biogeographer’s dream array of myzomelas, monarchs and white-eyes. A total of 146 species were seen (and another 5 heard) and included most of the available endemics, but we also enjoyed a close insight into the lifestyle and culture of this traditional Pacific country, and into the complex geography of the beautiful forests and islet-studded reefs. -

Habitat Selection by Two K-Selected Species: an Application to Bison and Sage Grouse

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2013-12-01 Habitat Selection by Two K-Selected Species: An Application to Bison and Sage Grouse Joshua Taft Kaze Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Animal Sciences Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Kaze, Joshua Taft, "Habitat Selection by Two K-Selected Species: An Application to Bison and Sage Grouse" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 4284. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4284 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Habitat Selection by Two K-Selected Species: An Application to Bison and Sage-Grouse in Utah Joshua T. Kaze A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science Randy T. Larsen, Chair Steven Peterson Rick Baxter Department of Plant and Wildlife Science Brigham Young University December 2013 Copyright © 2013 Joshua T. Kaze All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Habitat Selection by Two K-Selected Species: An Application to Bison and Sage-Grouse in Utah Joshua T. Kaze Department of Plant and Wildlife Science, BYU Masters of Science Population growth for species with long lifespans and low reproductive rates (i.e., K- selected species) is influenced primarily by both survival of adult females and survival of young. Because survival of adults and young is influenced by habitat quality and resource availability, it is important for managers to understand factors that influence habitat selection during the period of reproduction. -

Predators As Agents of Selection and Diversification

diversity Review Predators as Agents of Selection and Diversification Jerald B. Johnson * and Mark C. Belk Evolutionary Ecology Laboratories, Department of Biology, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-801-422-4502 Received: 6 October 2020; Accepted: 29 October 2020; Published: 31 October 2020 Abstract: Predation is ubiquitous in nature and can be an important component of both ecological and evolutionary interactions. One of the most striking features of predators is how often they cause evolutionary diversification in natural systems. Here, we review several ways that this can occur, exploring empirical evidence and suggesting promising areas for future work. We also introduce several papers recently accepted in Diversity that demonstrate just how important and varied predation can be as an agent of natural selection. We conclude that there is still much to be done in this field, especially in areas where multiple predator species prey upon common prey, in certain taxonomic groups where we still know very little, and in an overall effort to actually quantify mortality rates and the strength of natural selection in the wild. Keywords: adaptation; mortality rates; natural selection; predation; prey 1. Introduction In the history of life, a key evolutionary innovation was the ability of some organisms to acquire energy and nutrients by killing and consuming other organisms [1–3]. This phenomenon of predation has evolved independently, multiple times across all known major lineages of life, both extinct and extant [1,2,4]. Quite simply, predators are ubiquitous agents of natural selection. Not surprisingly, prey species have evolved a variety of traits to avoid predation, including traits to avoid detection [4–6], to escape from predators [4,7], to withstand harm from attack [4], to deter predators [4,8], and to confuse or deceive predators [4,8]. -

Short Note Preliminary Survey of the Bird Assemblage at Tanjong Mentong, Lake Kenyir, Hulu Terengganu, Malaysia

Tropical Natural History 15(1): 87-90, April 2015 2015 by Chulalongkorn University Short Note Preliminary Survey of the Bird Assemblage at Tanjong Mentong, Lake Kenyir, Hulu Terengganu, Malaysia 1,2* 3 MUHAMMAD HAFIZ SULAIMAN , MUHAMMAD EMBONG , MAZRUL A. 2 4 4 MAMAT , NURUL FARAH DIYANA A. TAHIR , NURSHILAWATI A. LATIP , 4 4 RAFIK MURNI AND M. ISHAM M. AZHAR 1 Institute of Kenyir Research, 2 School of Marine Science and Environment, 3 School of Fundamental Science, Universiti Malaysia Terengganu, 21030 Kuala Terengganu, Terengganu, MALAYSIA 4 Fakulti Sains & Teknologi Sumber, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak, 94300 Kota Samarahan, Sarawak, MALAYSIA * Corresponding Author: Muhammad Hafiz Sulaiman ([email protected]/ [email protected]) Received: 6 July 2014; Accepted: 2 March 2015 Malaysia has 789 bird species recorded above the ground. Mist-nets were tended by Avibase1, while2 lists 695 species. More every 2–3 h from 0730 until 1930. The total than 40 bird species are considered as trapping efforts were 49 net-days. All endemic to Malaysia and are mostly found captured birds were identified following6,7,8. in Sabah and Sarawak3. At least 45 species A total of 21 individual birds comprised were classified as endangered largely due to of 12 species belonging to 10 families and habitat degradation and illegal poaching2,3,4. 11 genera were recorded during the To date, 55 IBA areas covering 5,135,645 sampling period (Table 1). Of the 10 ha (51, 356 km2) have been identified in families of birds recorded, only one species Malaysia2 including Taman Negara was represented per family except for (National Park) includes Kenyir Lake (Tasik Nectariniidae and Dicaeidae with two Kenyir). -

Normal Template

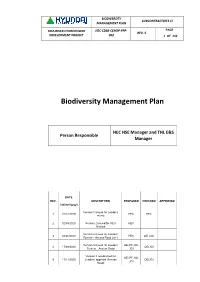

BIODIVERSITY SUBCONTRACTOR’S CI MANAGEMENT PLAN TINA RIVER HYDROPOWER HEC-CDSB-CEMSP-PPP- PAGE REV. 5 DEVELOPMENT PROJECT 002 1 OF 132 Biodiversity Management Plan HEC HSE Manager and THL E&S Person Responsible Manager DATE REV. DESCRIPTION PREPARED CHECKED APPROVED (dd/mm/yyyy) Version 1 issued for Lender’s 1 31/12/2019 HEC HEC review 2 02/05/2020 Version 2 issued for OE’s HEC Review Version 2 issued for Lenders’ 3 02/06/2020 HEC OE (JG) Review – Access Road Lot 1 Version 3 issued for Lenders’ OE (PF, KS, 4 17/09/2020 OE(JG) Review – Access Road JG) Version 3 resubmitted for OE (PF, KS, 5 13/11/2020 Lenders’ approval (Access OE(JG) JG) Road) BIODIVERSITY SUBCONTRACTOR’S CI MANAGEMENT PLAN TINA RIVER HYDROPOWER HEC-CDSB-CEMSP-PPP- PAGE REV. 5 DEVELOPMENT PROJECT 002 2 OF 132 Revision Log Date Revised Detail Rev. (dd/mm/yyyy) Item Page Article Description BIODIVERSITY SUBCONTRACTOR’S CI MANAGEMENT PLAN TINA RIVER HYDROPOWER HEC-CDSB-CEMSP-PPP- PAGE REV. 5 DEVELOPMENT PROJECT 002 3 OF 132 CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 8 1.1 PURPOSE AND SCOPE 8 1.2 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES 10 1.3 MANAGEMENT APPROACH 11 1.3.1 Adaptive Management 11 1.3.2 Ecosystem Approach 14 1.3.3 Four BMP Elements 14 1.3.4 Biodiversity Capacity Support and Stakeholder Engagement 15 1.4 UPDATES 16 1.5 DEFINITIONS 16 2 BACKGROUND TO THE PROJECT 18 3 ECOLOGICAL STUDIES UNDERTAKEN 19 4 BIODIVERSITY CONTEXT 21 4.1 REGIONAL BIODIVERSITY CONTEXT 21 4.2 LOCAL BIODIVERSITY CONTEXT 22 4.2.1 Terrestrial Ecology 23 4.2.2 Aquatic Ecology 27 5 EXISTING PRESSURES ON LOCAL BIODIVERSITY 29 5.1 CLEARING -

Seventh Grade

Name: _____________________ Maui Ocean Center Learning Worksheet Seventh Grade Our mission is to foster understanding, wonder and respect for Hawai‘i’s Marine Life. Based on benchmarks SC.6.3.1, SC. 7.3.1, SC. 7.3.2, SC. 7.5.4 Maui Ocean Center SEVENTH GRADE 1 Interdependent Relationships Relationships A food web (or chain) shows how each living thing gets its food. Some animals eat plants and some animals eat other animals. For example, a simple food chain links plants, cows (that eat plants), and humans (that eat cows). Each link in this chain is food for the next link. A food chain always starts with plant life and ends with an animal. Plants are called producers (they are also autotrophs) because they are able to use light energy from the sun to produce food (sugar) from carbon dioxide and water. Animals cannot make their own food so they must eat plants and/or other animals. They are called consumers (they are also heterotrophs). There are three groups of consumers. Animals that eat only plants are called herbivores. Animals that eat other animals are called carnivores. Animals and people who eat both animals and plants are called omnivores. Decomposers (bacteria and fungi) feed on decaying matter. These decomposers speed up the decaying process that releases minerals back into the food chain for absorption by plants as nutrients. Do you know why there are more herbivores than carnivores? In a food chain, energy is passed from one link to another. When a herbivore eats, only a fraction of the energy (that it gets from the plant food) becomes new body mass; the rest of the energy is lost as waste or used up (by the herbivore as it moves). -

Lesser Sundas and Remote Moluccas

ISLANDS OF THE LESSER SUNDAS AND REMOTE MOLUCCAS 12 August – 7 October 2009 and 27 October - 7 November 2009 George Wagner [email protected] ISLANDS VISITED: Bali, Sumba, Timor, Flores, Komoto, Ambon, Tanimbars, Kais, Seram and Buru INTRODUCTION Indonesia, being a nation of islands, contains over 350 endemic species of birds. Of those, over 100 are only found in the Lesser Sundas and remote Moluccas. Having visited Indonesia in past years, I knew it to be safe and cheap for independent birders like myself. I decided to dedicate some four months to the process of birding these remote destinations. Richard Hopf, whom I have joined on other trips, also expressed interest in such a venture, at least for the Lesser Sundas. We started planning a trip for July 2009. Much of the most recent information in the birding public domain was in the form of tour trip reports, which are self- serving and don’t impart much information about specific sites or logistics. There are a few exceptions and one outstanding one is the trip report by Henk Hendriks for the Lesser Sundas (2008). It has all the information that anyone might need when planning such a trip, including maps. We followed it religiously and I would encourage others to consult it before all others. My modest contribution in the form of this trip report is to simply offer an independent approach to visiting some of the most out of the ordinary birding sites in the world. It became clear from the beginning that the best approach was simply to go and make arrangements along the way. -

"Species Richness: Small Scale". In: Encyclopedia of Life Sciences (ELS)

Species Richness: Small Advanced article Scale Article Contents . Introduction Rebecca L Brown, Eastern Washington University, Cheney, Washington, USA . Factors that Affect Species Richness . Factors Affected by Species Richness Lee Anne Jacobs, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA . Conclusion Robert K Peet, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA doi: 10.1002/9780470015902.a0020488 Species richness, defined as the number of species per unit area, is perhaps the simplest measure of biodiversity. Understanding the factors that affect and are affected by small- scale species richness is fundamental to community ecology. Introduction diversity indices of Simpson and Shannon incorporate species abundances in addition to species richness and are The ability to measure biodiversity is critically important, intended to reflect the likelihood that two individuals taken given the soaring rates of species extinction and human at random are of the same species. However, they tend to alteration of natural habitats. Perhaps the simplest and de-emphasize uncommon species. most frequently used measure of biological diversity is Species richness measures are typically separated into species richness, the number of species per unit area. A vast measures of a, b and g diversity (Whittaker, 1972). a Di- amount of ecological research has been undertaken using versity (also referred to as local or site diversity) is nearly species richness as a measure to understand what affects, synonymous with small-scale species richness; it is meas- and what is affected by, biodiversity. At the small scale, ured at the local scale and consists of a count of species species richness is generally used as a measure of diversity within a relatively homogeneous area. -

A Distinctive New Species of Flowerpecker (Passeriformes: Dicaeidae) from Borneo

This is a repository copy of A distinctive new species of flowerpecker (Passeriformes: Dicaeidae) from Borneo. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/155358/ Version: Published Version Article: SAUCIER, J.R., MILENSKY, C.M., CARABALLO-ORTIZ, M.A. et al. (3 more authors) (2019) A distinctive new species of flowerpecker (Passeriformes: Dicaeidae) from Borneo. Zootaxa, 4686 (4). pp. 451-464. ISSN 1175-5326 10.11646/zootaxa.4686.4.1 Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence. This licence allows you to distribute, remix, tweak, and build upon the work, even commercially, as long as you credit the authors for the original work. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Zootaxa 4686 (4): 451–464 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) https://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2019 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4686.4.1 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:2C416BE7-D759-4DDE-9A00-18F1E679F9AA A distinctive new species of flowerpecker (Passeriformes: Dicaeidae) from Borneo JACOB R. SAUCIER1, CHRISTOPHER M. MILENSKY1, MARCOS A. CARABALLO-ORTIZ2, ROSLINA RAGAI3, N. FARIDAH DAHLAN1 & DAVID P. EDWARDS4 1Division of Birds, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, MRC 116, Washington, D.C. -

Moluccas 15 July to 14 August 2013 Henk Hendriks

Moluccas 15 July to 14 August 2013 Henk Hendriks INTRODUCTION It was my 7th trip to Indonesia. This time I decided to bird the remote eastern half of this country from 15 July to 14 August 2013. Actually it is not really a trip to the Moluccas only as Tanimbar is part of the Lesser Sunda subregion, while Ambon, Buru, Seram, Kai and Boano are part of the southern group of the Moluccan subregion. The itinerary I made would give us ample time to find most of the endemics/specialties of the islands of Ambon, Buru, Seram, Tanimbar, Kai islands and as an extension Boano. The first 3 weeks I was accompanied by my brother Frans, Jan Hein van Steenis and Wiel Poelmans. During these 3 weeks we birded Ambon, Buru, Seram and Tanimbar. We decided to use the services of Ceisar to organise these 3 weeks for us. Ceisar is living on Ambon and is the ground agent of several bird tour companies. After some negotiations we settled on the price and for this Ceisar and his staff organised the whole trip. This included all transportation (Car, ferry and flights), accommodation, food and assistance during the trip. On Seram and Ambon we were also accompanied by Vinno. You have to understand that both Ceisar and Vinno are not really bird guides. They know the sites and from there on you have to find the species yourselves. After these 3 weeks, Wiel Poelmans and I continued for another 9 days, independently, to the Kai islands, Ambon again and we made the trip to Boano. -

Muruk July 2007 Vol 8-3-1

Editorial There has been a 7-year gap between the last issue of the Papua New Guinea Birdwatching Society’s journal Muruk in 2000 (Vol. 8: 2) and this issue, which completes that volume. It serves a valuable purpose documenting significant records of New Guinea birds, and publishing notes and papers relevant to New Guinea ornithology. Thanks are due to Conservation International’s Melanesia Centre for Biodiversity Conservation (funded by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation) for coming up with funds for the printing of the journal, with particular thanks to Roger James. The idea is to clear a large backlog of records, and publish articles relating to New Guinea ornithology, with the help of an editorial team: Editor - Phil Gregory Editorial consultants: K. David Bishop, Ian Burrows, Brian Coates, Guy Dutson, Chris Eastwood. We would like feedback about the direction the journal should take; it has been a useful reference resource over the years and is cited in many publications. Current thinking is to publish two issues per annum, with thoughts about expanding coverage to include other nearby areas such as Halmahera and the Solomon Islands, which have a large New Guinea component to the avifauna. The Pacific region as a whole is poorly served and there may be scope to include other parts of Melanesia and Polynesia. We now complete the old pre-2000 subscriptions with this issue, which is sent free to former subscribers, and invite new subscriptions. Editorial address: PO Box 387, Kuranda, Queensland 4881, Australia. Email - [email protected] Significant Sightings from Tour Reports Compiled and edited by Phil Gregory More and more companies are offering tours to PNG, mostly doing the same circuit but still coming up with interesting records or little known or rare species, breeding data or distributional information.