OFFICIAL REPORT (Hansard)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BBC Outreach Corporate Responsibility Report 2007/08

1 BBC Corporate Responsibility Report 2007/08 BBC Corporate Responsibility Report 2007/08 2 Welcome Welcome to the BBC Corporate Responsibility Report produced by BBC Outreach. BBC Outreach’s work is about making the BBC’s commitment to our stakeholders stronger and more inclusive. It’s about making us a better business in the way we work and the way we impact and interact with communities and all those to whom we broadcast. Our report will demonstrate how outreach, corporate responsibility and partnership work directly supports the BBC’s six Public Purposes and is vital if we are to achieve them. It will also cover what the BBC does to ensure that our operations, including our impact on the environment, are managed in a responsible manner. We hope you find the content of this report interesting and welcome your feedback. Alec McGivan Head of BBC Outreach BBC Outreach Room 4171, White City, 201 Wood Lane, London W12 7TS T: 020 8752 6761 E: [email protected] BBC Corporate Responsibility Report 2007/08 3 ContentsContents Introduction 04 Citizenship 08 Learning 14 Creativity 18 Community 24 Global 31 Communications 36 Environment 41 Charity 47 Our business 54 Verification 62 4 4 Introduction BBC Corporate Responsibility Report 2007/08 Why should you read this report? This report is written for the many stakeholders who have an interest in the BBC. The BBC exists to serve the public, and has a responsibility to account to licence fee payers everywhere for its actions. “ The BBC’s role and remit is set out in its Royal Charter, established by Being” responsible the Government on behalf of the Crown and debated in Parliament. -

Down Syndrome from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Jump To: Navigation, Search

Down syndrome From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search Down syndrome Classification and external resources Boy with Down syndrome assembling a bookcase ICD-10 Q 90. ICD-9 758.0 OMIM 190685 DiseasesDB 3898 MedlinePlus 000997 eMedicine ped/615 MeSH [2] Down syndrome (the most common term in US English), Down's syndrome (standard in the rest of the English-speaking world), trisomy 21, or trisomy G is a chromosomal disorder caused by the presence of all or part of an extra 21st chromosome. It is named after John Langdon Down, the British doctor who described the syndrome in 1866. The disorder was identified as a chromosome 21 trisomy by Jérôme Lejeune in 1959. The condition is characterized by a combination of major and minor differences in structure. Often Down syndrome is associated with some impairment of cognitive ability and physical growth as well as facial appearance. Down syndrome in a baby can be identified with amniocentesis during pregnancy or at birth. Individuals with Down syndrome tend to have a lower than average cognitive ability, often ranging from mild to moderate developmental disabilities. A small number have severe to profound mental disability. The incidence of Down syndrome is estimated at 1 per 800 to 1,000 births, although these statistics are heavily influenced by older mothers. Other factors may also play a role. Many of the common physical features of Down syndrome may also appear in people with a standard set of chromosomes, including microgenia (an abnormally small chin)[1], an unusually round face, macroglossia [2] (protruding or oversized tongue), an almond shape to the eyes caused by an epicanthic fold of the eyelid, upslanting palpebral fissures (the separation between the upper and lower eyelids), shorter limbs, a single transverse palmar crease (a single instead of a double crease across one or both palms, also called the Simian crease), poor muscle tone, and a larger than normal space between the big and second toes. -

Line of Duty Series 5 - Episode 4

Line of Duty Series 5 - Episode 4 Post Production Script – UK TX Version. 12th April 2019. 09:59:30 VT CLOCK (30 secs) World Productions Line of Duty Series 5 - Episode 4 Prog no. DRII788B/01 09:59:57 CUT TO BLACK 10:00:00 SUPER CAPTION: PREVIOUSLY Music 10:00:00 DUR: 2’37”. Powell’s office Police Services Building. Specially composed by Carly POWELL Paradis. It’s called Operation Pear Tree. | Our brief was to embed an | undercover officer within an | organised crime group. | | Powell turns her computer towards them. | | POWELL (CONT’D) | Detective Sergeant John Corbett. | | Steve brings up the file and photo of Corbett. | | STEVE | His files were erased from the | police database, his phone number | and email deleted. Corbett was | given a new identity. | | CUT TO BLACK: | | 10:00:17 SUPER CAPTION: STEPHEN GRAHAM | | CUT TO: | | Corbett looking at the laptop message from | unknown. | | UNKNOWN | (Text.) | What is it? | | Corbett blurts it. | | CORBETT | It’s the Eastfield Depot. It’s | where all the police forces in the | region store seized contraband. | Drugs. Cash. Jewels. Precious | metals. This could be bigger than | Brinks-Mat. | 1 10:00:28 CUT TO BLACK: | | 10:00:29 SUPER CAPTION: MARTIN COMPSTON VICKY McCLURE | | HASTINGS (V.O.) | There’s a strong suggestion... | | CUT TO: | | Steve looking through a scope. McQueen outside | Cafferty’s house. | | | HASTINGS (CONT’D) | ... women in that block are being | kept in modern day slavery to | provide sexual services. Our duty | is to protect them. And we will | raid the house and raid the print | shop. | | See AFO’s raid house and forensic investigators | in white suits outside the print shop. -

By Allan Sutherland Chronology of Disability Arts by Allan Sutherland 1977 - April 2017 an Ongoing Project

Chronology of Disability Arts 1977 - 2017 by Allan Sutherland Chronology of Disability Arts by Allan Sutherland 1977 - April 2017 An ongoing project Sources: Allan Sutherland’s personal archives Disability Arts in London magazine (DAIL) Disability Arts magazine (DAM) Shape Arts Disability Arts Online Commissioned by NDACA Timeline cover design and text formating by Liam Hevey, NDACA Producer 1976 1984 • SHAPE founded. • Fair Play ‘campaign for disabled people in the arts’ founded. 1977 • Strathcona Theatre Company, ‘Now and Then’. • Basic Theatre Company founded by Ray Harrison • Graeae Theatre Company, ‘Cocktail Cabaret’. Graham. Devised by the company. Directed by Caroline Noh. • Graeae Theatre Company, ‘Practically Perfect’. 1980 Theatre in Education show. Written by Ashley Grey. • Graeae (Theatre group of Disabled People) Directed by Geoff Armstrong. founded by Nabil Shaban and Richard Tomlinson. • ‘Choices’. Central TV Programme about the First production: ‘Sideshow’, devised by Richard Theatre In Education work of Graeae Theatre Tomlinson and the company. Company. • British Council of Organisations of Disabled People founded. 1985 • GLC funds 7 month pioneer project for ‘No 1981 Kidding’, a ‘project using puppets to increase • International Year of Disabled People. awareness of disability in Junior Schools’. Company • ‘Carry On Cripple’ season of feature films about of four performers with and without disabilities. disability at National Film Theatre, programmed by • Ellen Wilkie, ‘Pithy Poems’ published. Allan Sutherland and Steve Dwoskin. • Strathcona Theatre Company, ‘Tonight at Eight’ • Artsline founded. 25th October • Path Productions founded, ‘then the only • Samena Rama speaks on Disability and company to integrate the able-bodied, physically Photography as part of Black Arts Forum weekend and mentally disabled performers’. -

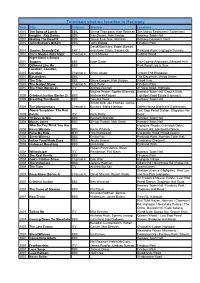

Televison Shot on Location in Haringey

Televison shot on location in Haringey Year Title Channel Starring Locations 2010 The Song of Lunch BBC Emma Thompson, Alan Rickman San Marco Restaurant (Tottenham) 2010 Imagine - Ray Davies BBC Ray Davies, Alan Yentob Hornsey Town Hall 2010 Waking The Dead IX BBC Trevor Eve, Sue Johnston Hornsey Coroners Court 2010 John Bishop's Britain BBC John Bishop Finsbury Park David Morrissey, Eddie Marsan 2010 Thorne: Scaredy Cat SKY 1 and Aidan Gillen, Sandra Oh Parkland Walk / Highgate Tunnels 2010 Chris Moyles Quiz Night Channel 4 Chris Moyles Coldfall Wood Nigel Slater's Simple 2010 Suppers BBC Nigel Slater Golf Course Allotments (Muswell Hill) 2010 Different Like Me BBC Park Road Lido & Gym Location, Location, 2010 Location Channel 4 Kirsty Allsop Crouch End Broadway 2010 Eastenders BBC The Decoreum, Wood Green 2010 The Trip BBC Steve Coogan, Rob Brydon Wood Vale 2010 The Gadget Show Channel 5 Suzi Perry Finsbury Park 2010 The Fixer (Series 2) ITV Andrew Buchan 21 View Road, Highgate Maxine Peake, Sophie Okonedo, Hornsey Town Hall (Crouch End), 2009 Criminal Justice (Series 2) BBC Mathew McFadyen Lightfoot Road Estate (Hornsey) 2009 Breaking The Mould BBC Dominic West Hornsey Town Hall Simon Bird, Joe Thomas, James 2009 The Inbetweeners Channel 4 Buckley, Blake Harrison Opera House Nightclub (Tottenham) Above Suspicion: The Red Last Stop Petrol Station, Stapleton Hall 2009 Dahlia ITV Kelly Reilly Road 2008 10 Days to War BBC Kenneth Branagh Hornsey Town Hall 2008 Moses Jones BBC Shaun Parkes. Matt Smith Hornsey Town Hall Who Do You Think -

LIVING WITHOUT FEAR Production Support Pack

LIVING WITHOUT FEAR Production Support Pack The Order of Malta Volunteers presents Living Without Fear By Blue Apple Theatre Wednesday 26th March 2014 at Westminster Cathedral Hall Blending drama and dance, humour and tragedy, the performance challenges and empowers each one of us to end disability hate crime. Director: Peter Clerke Choreography: Jo Harris Production Manager: Ben Ward Design: Su Houser LX Design: Mark Dymock Stage Manager: Joe Price Quotes About Living Without Fear (2013 Tour) “Startling. Wonderful. One of the most powerful performances seen in Winchester for many years.” The Hampshire Chronicle “A profoundly moving and challenging production. It deserves to be seen by a wide audience.” Professor Lord Alton “One of the most powerful presentations that I have seen and it reminded me so powerfully of the talents and potential amongst people with learning disability. “ Dame Philippa Russell DBE, Chair, Standing Commission on Carers “This is spookily accurate...really, really realistic, you cannot re-create this experience. Police officers should see this portrayal and the impact it has on a person.” Police Officer, Nettley, Hampshire Police HQ “The play is remarkable at so many different levels – it is genuinely a prophetic work'” Revd Canon David Williams “Very thought provoking, beautiful dancing, fantastic acting. I would like to see more.” Member, Surrey partnership board “I was struck by the strong message and how simply it was put across. All staff should have the opportunity to see this production.” Surrey Safeguarding Advisor “They are such an inspiring group.” Dame Anne Begg, Chair of Work and Pensions Select Committee “Moving, sad, upsetting and really hard hitting. -

Radio 4 Listings for 14 – 20 March 2009 Page 1 of 12 SATURDAY 14 MARCH 2009 Stewart and Mad Money's Jim Cramer Has Been Causing a Stir

Radio 4 Listings for 14 – 20 March 2009 Page 1 of 12 SATURDAY 14 MARCH 2009 Stewart and Mad Money's Jim Cramer has been causing a stir. SAT 13:00 News (b00j22t7) Richard Lister reports on whether the financial media had The latest national and international news from BBC Radio 4. SAT 00:00 Midnight News (b00j1fhs) deliberately obscured the growing banking crisis in the chase The latest national and international news from BBC Radio 4. for ratings and profits. Followed by weather. SAT 13:10 Any Questions? (b00j1f9m) Thought for the day with Canon David Winter. Jonathan Dimbleby chairs the topical debate in Londonderry. The panel are Professor Monica McWilliams, chief SAT 00:30 Book of the Week (b00hz020) Journalists Deborah Haynes and Sudarsan Raghavan discuss the commissioner of the Northern Ireland Human Rights The Settler's Cookbook judicial system in Iraq. Commission, Lord Paul Bew, Professor of Irish Politics at Queen's University, Belfast, political commentator and author Episode 5 Chancellor Alistair Darling discusses if the G20 countries will Eamonn McCann and editor-in-chief of The Economist, John be in agreement on the major issues. Micklethwait. Yasmin Alibhai-Brown reads her memoir of her childhood in Uganda and move to Britain in the 1970s. Jonah Fisher reports on the political tension in Madagascar which has brought the country to the brink of military SAT 14:00 Any Answers? (b00j22t9) Yasmin arrives in London in 1972 and finds a country rife with intervention. Jonathan Dimbleby takes listeners' calls and emails in response industrial unrest and casual racism. -

SAME HOUSE a Report by Vanessa Brooks

UK theatre featuring actors and performers with learning disabilities SEPARATE DOORS SAME HOUSE A report by Vanessa Brooks With interviews and insights from Access All Areas, Dark Horse, Hijinx and Hubbub Authorship This report is written entirely from the authors’ subjective point of view, contributions are attributed. Process The Separate Doors project is a collaboration between Vanessa Brooks and four theatre companies across the UK, Contents four directors and over thirty actors and performers with learning disabilities. Introduction page 3 Artistic Directors Nick Llewellyn of Access All Areas, Ben Pettitt-Wade Profile: Access All Areas page 10 of Hijinx, Jen Sumner of Hubbub and Executive Director Lynda Hornsby of Dark Horse took part in a phone interview, answering a Why do actors train? page 12 set of identical questions, and selected answers are included in the ‘Opinions’ section. Profile: Dark Horse page 14 Vanessa Brooks then visited each participant company and delivered The silent approach page 16 an identical ‘silent approach’ workshop, filmed an interview with a nominated actor/perfomer and with each director. A debatable glossary page 20 A short film complements this report. Profile: Hijinx page 22 Information for venues The purpose and potential collaborators page 24 The aim of the project is to throw a light on key producers and creators of work featuring actors and performers with learning Profile: Hubbub page 26 disabilities, to acknowledge success, chew over obstacles, consider objectives and to advance a shared ambition for a fully Whose stage is it anyway? page 28 representative UK theatre landscape. Opinions page 30 A further aim is to offer clarity to programmers, venues and others inspired by the idea of collaborating with companies at the cutting Final words and ideas page 38 edge of diverse and integrated work. -

British Broadcasting Corporation Disability Equality Scheme

British Broadcasting Corporation Disability Equality Scheme updated 2008 1 Foreword by the Chairman of the BBC Disability Equality Scheme Everyone in the UK, whatever their background, should get something of real value from the BBC. After all, everyone pays for it. One of the main roles of the BBC Trust is to listen hard to and understand the views of the public, in order to ensure that the BBC does as well as it can among every section of UK society. Around one in five of people living in the UK is disabled. This is not a homogenous group, but a range of people with a wide range of needs and views. The BBC Trust needs to understand these views in order to do its job. The Disability Equality Scheme is one way in which the BBC contributes to meeting the diverse needs and expectations of all audiences, and to enhancing the lives of people from a wide range of different communities and backgrounds. The BBC published its first Disability Equality Scheme in December 2006. This scheme outlines the framework for how the BBC will develop, implement, monitor and review its work towards achieving equality for disabled people (and their carers) in relation to its relevant public functions. The scheme is updated each year, and we will be carrying out a major review every three years. In the schemes, you will see our detailed progress report against actions we committed to in last year’s scheme. For example, following consultation we have modified our complaints procedures to increase their accessibility in a number of ways.