A Case Study of Rural-Urban Labour Migration in Shanxi Province

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Current Location: Project Information Newly Approved Projects by DNA of China (Total:61) (Up to May 17, 2011) Project Name Proje

Current Location: Project Information Newly Approved Projects by DNA of China (Total:61) (Up to May 17, 2011) Estimated Project Ave. GHG No. Project Name Project Owner CER Buyer Type Reduction (tCO2e/y) Inner Mongolia Chifeng Renewable Inner Mongolia Huifeng A&T Carbon Asset Co., 1 Mazongshan 49.5MW 119,776 energy New Energy Co., Ltd. Limited Wind Power Project Inner Mongolia Wutaohai Renewable Chifeng City Huifeng A&T Carbon Asset Co., 2 South Phase II Wind 114,725 energy New Energy Co., Ltd. Limited Power Project Fumeng Maniuhu Wind Renewable Fuxin Taihe Wind Power Camco Carbon Credits 3 104,040 Farm Project energy Co., Ltd. Limited Fumeng Gulibengao Renewable Fuxin Taihe Wind Power Camco Carbon Credits 4 103,656 Wind Farm Project energy Co., Ltd. Limited Inner Mongolia North China Power Renewable 5 Wulatehouqi Chaoge Generation Co., Ltd.of Camco Carbon Limited 119,340 energy Wind Farm Project Guodian Group Guodian Wuchuan Xiwulanbulang Renewable Guodian Wuchuan Wind 6 Camco Carbon Limited 103,963 Hongshan Wind Farm energy Power Co., Ltd. Phase II Project Shanxi Shuozhou Pinglu Renewable Shuozhou Pinglu Tianhui Camco Carbon Credits 7 Dashantai Wind Farm 92,761 energy Wind Power Co., Ltd Limited Project (Phase I) Shandong Kaitai Shandong Kaitai Renewable Bunge Emissions Holdings 8 Biomass Cogeneration Industrial Technologies 106,137 energy S.A.R.L. Project Co., Ltd. Huaneng Inner Mongolia Renewable Huaneng New Energy Carbon Resource 9 Manzhouli Donghu Wind 114,454 energy Industrial Co., Ltd Management S.A. Farm Project Huaneng Inner Mongolia Renewable Huaneng New Energy Carbon Resource 10 Chenbaerhuqi Daliang 117,534 energy Industrial Co., Ltd Management S.A. -

Tome Offers a Natural Way to View Things

16 | Wednesday, November 4, 2020 HONG KONG EDITION | CHINA DAILY YOUTH uesdays are special for One of the regular participants, some people in the county- Han Yanqing, 46, has followed the level city of Yuanping, reading club for years. Xinzhou, North China’s She used to work as a receptionist TShanxi province. They are literally at a local hotel in Yuanping and turning a new page on life. Once they joined the club to expand her get off work, they grab a pen, bring a knowledge. notebook and head for the Yuanping Han says she often found herself at Library. There the Time Reading a loss when the hotel guests would Club will meet and discuss books inquire about the local history and that its members have recently read. specialties of Yuanping. As Fu Such book readings and discus- noticed, Han was often an early sions have been hosted by the club’s arrival and took the front seat, listen- founder Fu Xiaoping for six years. ing attentively and taking notes from Since its establishment in time to time. December 2014, the club has held Years of participation has various reading-based events each increased her knowledge about the Tuesday evening, and launched 200 county-level city and allowed her to lectures delivered by established more effectively deal with guests’ artists and academics, to promote requests. reading and the development of a Even though Han was promoted reading society. to the hotel’s headquarters in down- The club has been called “a uni- town Xinzhou, where she now takes versity without walls” by its mem- charge of employee training, every bers, because it welcomes people Tuesday, Han returns to Yuanping from all walks of life, including to attend the sessions held at the farmers, workers, teachers, doctors reading club. -

Research on Planning and Design Strategy of Gully Ecology Park—Take Shanxi's Northern Gully Park As an Example

E3S Web of Conferences 53, 03021 (2018) https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/20185303021 ICAEER 2018 Research on planning and design strategy of Gully Ecology Park—Take Shanxi's Northern gully Park as an example Liu Rongrong *, Liu Yuanping College of Architect and Civil Engineering,Taiyuan University of Technology,Taiyuan 030024,China Abstract. The Li Cheng Northern gully Central Park is located between the new and old city of Li Cheng county, Changzhi city, Shanxi province. It is the link between the new and old urban areas and the ecological corridor of the central county. There are villages, water systems and abundant vegetation in the gully. Relying on the rich natural historical resources of the northern gully area, the leisure tourism service is developed, and the red cultural temperament of the area is combined to create a large green space central park, which integrates display, commemoration, sightseeing, rest, office and office. Based on the general idea of "water moisten garden, green shade garden and cultural nourish garden", we plan to build a homestead rural for urban people. 1 The general situation of Li Cheng According to the data of the northern gully of Li Cheng County County, Changzhi city, Shanxi province, the streams in the northern gully are flowing and the vegetation is flourishing. In the spring, the flower of apricot and pear 1.1 A survey of the history of Li Cheng County being to compete for opening up and the gully is in a vast expanse of white. Therefore, the North Square, also Li Cheng County is the county of Changzhi city of is known as the "white square", and the North Fang Shanxi province. -

The Inheritance and Development of Feng Yangko of Yuanping from the Perspective of Cultural Ecology

Open Journal of Social Sciences, 2020, 8, 198-206 https://www.scirp.org/journal/jss ISSN Online: 2327-5960 ISSN Print: 2327-5952 The Inheritance and Development of Feng Yangko of Yuanping from the Perspective of Cultural Ecology Zhenghui Jia College of Music, Shanxi University, Taiyuan, China How to cite this paper: Jia, Z. H. (2020). Abstract The Inheritance and Development of Feng Yangko of Yuanping from the Perspective In recent years, as an important part of the local cultural ecology, Feng Yangko of Cultural Ecology. Open Journal of Social of Yuanping has become a serious and even declining phenomenon. In order Sciences, 8, 198-206. to alleviate this endangered situation and promote its effective cultural inhe- https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2020.89014 ritance and innovative development, under the guidance of the Measures for Received: July 7, 2020 the Management of National Cultural Ecological Reserves and the principle Accepted: September 21, 2020 of holistic protection, this paper reconstructs the path of its inheritance and Published: September 24, 2020 development from the perspective of cultural ecology after the reflection of the current situation of Feng Yangko. Copyright © 2020 by author(s) and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Keywords Commons Attribution International Cultural Ecology, Feng Yangko, Inheritance, Development License (CC BY 4.0). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Open Access 1. Introduction For a long time, Feng Yangko of Yuanping, as a local excellent cultural ecologi- cal card, has been popular among the public with its diverse and friendly per- formance forms, novel and rich costumes and props, clever and unique dance movements, and lively and cheerful music lyrics. -

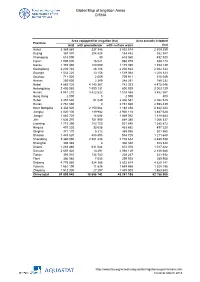

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA Area equipped for irrigation (ha) Area actually irrigated Province total with groundwater with surface water (ha) Anhui 3 369 860 337 346 3 032 514 2 309 259 Beijing 367 870 204 428 163 442 352 387 Chongqing 618 090 30 618 060 432 520 Fujian 1 005 000 16 021 988 979 938 174 Gansu 1 355 480 180 090 1 175 390 1 153 139 Guangdong 2 230 740 28 106 2 202 634 2 042 344 Guangxi 1 532 220 13 156 1 519 064 1 208 323 Guizhou 711 920 2 009 709 911 515 049 Hainan 250 600 2 349 248 251 189 232 Hebei 4 885 720 4 143 367 742 353 4 475 046 Heilongjiang 2 400 060 1 599 131 800 929 2 003 129 Henan 4 941 210 3 422 622 1 518 588 3 862 567 Hong Kong 2 000 0 2 000 800 Hubei 2 457 630 51 049 2 406 581 2 082 525 Hunan 2 761 660 0 2 761 660 2 598 439 Inner Mongolia 3 332 520 2 150 064 1 182 456 2 842 223 Jiangsu 4 020 100 119 982 3 900 118 3 487 628 Jiangxi 1 883 720 14 688 1 869 032 1 818 684 Jilin 1 636 370 751 990 884 380 1 066 337 Liaoning 1 715 390 783 750 931 640 1 385 872 Ningxia 497 220 33 538 463 682 497 220 Qinghai 371 170 5 212 365 958 301 560 Shaanxi 1 443 620 488 895 954 725 1 211 648 Shandong 5 360 090 2 581 448 2 778 642 4 485 538 Shanghai 308 340 0 308 340 308 340 Shanxi 1 283 460 611 084 672 376 1 017 422 Sichuan 2 607 420 13 291 2 594 129 2 140 680 Tianjin 393 010 134 743 258 267 321 932 Tibet 306 980 7 055 299 925 289 908 Xinjiang 4 776 980 924 366 3 852 614 4 629 141 Yunnan 1 561 190 11 635 1 549 555 1 328 186 Zhejiang 1 512 300 27 297 1 485 003 1 463 653 China total 61 899 940 18 658 742 43 241 198 52 -

Title of Paper

International Forum on Energy, Environment Science and Materials (IFEESM 2015) The achievement and prospect of Taiyuan’s city planning development ――The features of the city planning in German occupation period and their enlightenment to Taiyuan’s city construction Xuhui Wang1, a *, Yuanping Liu2,b 1Departments of architecture , Taiyuan University of Technology ,Shanxi,China 2Departments of architecture , Taiyuan University of Technology ,Shanxi,China [email protected], [email protected] *Xuhui Wang KEYWORD: city planning; city construction ABSTRACT: City planning is a subject to deal with the city and the engineering construction, economy, society, land using layout of its nearby areas. Besides, it is to predict the future development. City planning can disclose the developmental overview and regularity of a city to some extend, which is a blueprint to a city’s developmental planning. A better planning can bring a good scenery to a city. It can also provide a developmental direction for a city in some ways at the same time. The thesis aims to illustrate a good city planning can have positive promoting functions to a city’s construction by introducing the city planning features of Qingdao in German occupation period and it summarizes the enlightenments brought to Taiyuan’s present city construction. Introduction A good city’s planning is indispensable for each city’s development. The plan for a city can be carried out from both macro and micro aspects, that is to say, general and detail planning. From the macro aspect, a city’s layout and development features should be considered in a city planning. The elements like the city’s transportation, function zones, general overview, city orientation, water intaking, anti flood and earthquake should be considered. -

Research Cottrell Dry Cooling

Research Cottrell Dry Cooling Riyadh Power Plant Air Cooled Condenser Air Cooled Condensers The Research Cottrell Dry Cooling (RCDC) Air Cooled Condenser (ACC) represents state-of-the-art design and incorporates developments and lessons learned from decades of experience. The ACC design is optimized for each client to provide a guaranteed maximum efficiency depending on the client’s criteria for balancing capital and operating costs. Each section of the ACC is designed for performance, cost and constructability. The entire system is guaranteed; RCDC undertakes integral studies related to the steam ducts and manifolds, the steel support structure, condensate piping, and other special studies as appropriate in order to address design issues including cold weather operation, fan stall, noise, wind effects, and seismic activity. Considerations include delivery logistics, construction planning and sequencing, including design details for constructability. the process ctec™ single row tube technology The RCDC ACC design is based on a single row of condenser The RCDC CTEC™ single row tube is based on these decades tubes over which forced draft air passes to condense turbine of industry experience to provide a state-of-the-art brazed fin exhaust steam. This steam is then conveyed in large steam tube design which provides multiple benefits including: ducts and manifolds to the overhead steam headers. The fin tubes are arranged into A-frame bundles with forced draft Winter freeze protection (–40°C and below) provided by large multiblade fans. Each of these modules is Lowest noise levels further organized into streets depending on the size of the Lowest auxiliary power (low pressure drops) project. -

Shanxi Small Cities and Towns Development Demonstration Sector Project

Environmental Assessment Report Summary Environmental Impact Assessment Project Number: 42383 October 2008 People’s Republic of China: Shanxi Small Cities and Towns Development Demonstration Sector Project Prepared by the Shanxi provincial government for the Asian Development Bank (ADB). The summary environmental impact assessment is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 17 October 2008) Currency Unit – yuan (CNY) CNY1.00 = $0.1461 $1.00 = CNY6.8435 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank BOD5 – 5-day biochemical oxygen demand ClO2 – chlorine dioxide CO2 – carbon dioxide CODCr – chemical oxygen demand determined through the dichromate reflux method CSC – construction supervision company DMF – design and monitoring framework EA – executing agency EAMF – environmental assessment and management framework EIA – environmental impact assessment EMC – environmental management consultant EMP – environmental management plan EPB – environmental protection bureau FSR – feasibility study report GDP – gross domestic product GHG – greenhouse gas HDPE – high-density polyethylene IA – implementing agency LDI – local design institute MSW – municipal solid waste NH3-N – ammonia nitrogen NOx – nitrogen oxides O&M – operation and maintenance pH – a unit of acidity PM10 – particulate matter ≤10 micrometers in diameter PMO – project management office PPTA – project preparatory technical assistance -

Resource-Based City Type and Reforming Strategy Discussion and Research

2016 4th International Conference on Advances in Social Science, Humanities, and Management (ASSHM 2016) ISBN: 978-1-60595-412-7 Resource-based City Type and Reforming Strategy Discussion and Research Junwei Xing1 Abstract The resource-based city can divides according to the Israeli resource type and development phase two big standards. The resource-based city economic transformation strategy first should from the macroscopic level, seek for the regional economic development the new superiority, next should act according to the new regional development favorable condition that establishes the pattern of industrial transformation from the microscopic level. Keywords. Resource-based City; Type; Reforming Strategy. 1. INTRODUCTION The resource-based city is our country important foundation energy and raw material supplying place, development display excessively significant role to our country national economy. But as a result of the non-renewability of finiteness and resources of resource, the resource-based city sooner or later must face the issue of economic transformation, otherwise possibly enters the winter. At present, a considerable number of resource-based cities in China have been facing a series of economic and social problems such as resource depletion, economic recession, environmental degradation, unemployment and the increase of the poor population. These resource-based cities have become the problem areas in which regional contradictions are concentrated. Therefore, how to guide these cities to successfully transform and achieve sustainable development has become an important topic of concern for both academia and government. 2. Classification of Resource-based Cities Resource based cities are mainly built up by the development of resources. Although the overall pattern of urban growth and development is similar, because of the differences of the economic development factors such as natural resources, geographical conditions and other economic development factors, the difference between different resource cities is very large. -

Minimum Wage Standards in China August 11, 2020

Minimum Wage Standards in China August 11, 2020 Contents Heilongjiang ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Jilin ............................................................................................................................................................... 3 Liaoning ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region ........................................................................................................... 7 Beijing......................................................................................................................................................... 10 Hebei ........................................................................................................................................................... 11 Henan .......................................................................................................................................................... 13 Shandong .................................................................................................................................................... 14 Shanxi ......................................................................................................................................................... 16 Shaanxi ...................................................................................................................................................... -

Natural Resources, Rent Dependence, and Public Goods Provision in China: Evidence from Shanxi’S County-Level Governments Yuyi Zhuang* and Guang Zhang

Zhuang and Zhang The Journal of Chinese Sociology (2016) 3:20 The Journal of DOI 10.1186/s40711-016-0040-3 Chinese Sociology RESEARCH Open Access Natural resources, rent dependence, and public goods provision in China: evidence from Shanxi’s county-level governments Yuyi Zhuang* and Guang Zhang * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract School of Public Affairs, Xiamen University, Xiamen, Fujian Province This paper investigates how natural-resource endowments affect the provision of 361005, People’s Republic of China local public goods in China. According to fiscal sociology, due to the rentier effect, resource-rich local governments tend to have more state autonomy and are less responsive to society, resulting in poor governance. Moreover, due to political myopia, resource-abundant local governments tend to neglect the accumulation of human capital. Shanxi’s county-level governments are excellent samples to test these hypotheses. Statistical results show that resource-abundant local governments tend to spend less on social expenditures as well as specific education, social security and healthcare, and environmental protection expenditures. Meanwhile, coal-rich governments spend significantly more on self-serving administrative expenditures. The results suggest that negative impacts of natural resources on governmental fiscal extraction and expenditure behaviors are an important causal mechanism of the resource-curse hypothesis. To curb this problem, the current fiscal system needs to be reformed accordingly. Keywords: Resource curse, Coal, Public goods provision, Shanxi Province Introduction Why are developing countries and regions rich in natural resources often characterized by slow economic growth? Exploring this “resource curse,” economists, political scien- tists, and sociologists have put forward various causal mechanisms and explanations. -

Proposed Loan and Administration of Grant People's Republic of China

Report and Recommendation of the President to the Board of Directors Project Number: 42383 November 2009 Proposed Loan and Administration of Grant People’s Republic of China: Shanxi Small Cities and Towns Development Demonstration Sector Project CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 17 November 2009) Currency Unit – yuan (CNY) CNY1.00 = $0.1464 $1.00 = CNY6.8270 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank EIA – environmental impact assessment EIRR – economic internal rate of return FIRR – financial internal rate of return ICB – international competitive bidding LIBOR – London interbank offered rate NCB – national competitive bidding NPV – net present value O&M – operation and maintenance PCG Pingyao county government PLG – project leading group PMO – project management office PRC – People’s Republic of China PPMS – project performance management system QCBS – quality- and cost-based selection SEIA – summary environmental impact assessment SPG – Shanxi provincial government TA – technical assistance WACC – weighted average cost of capital XCG – Xiaoyi city government YCG – Youyu county government WEIGHTS AND MEASURES km – kilometer km2 – square kilometer m2 – square meter m3 – cubic meter NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the Government ends on 31 December. (ii) In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. Vice-President C. Lawrence Greenwood, Jr., Operations 2 Director General K. Gerhaeusser, East Asia Department (EARD) Team leader A. Leung, Director, Urban and Social Sectors, EARD Team members C. Chu, Project Management Officer, EARD H. Gunatilake, Senior Economist, Economics and Research Department M. Gupta, Senior Social Development Specialist (Safeguards), EARD S. W. Handayani, Senior Social Development Specialist, Regional and Sustainable Development Department J. Masic, Urban Development Specialist, EARD S. Noda, Transport Specialist, EARD X.