Yipster Gentrification of Weird, White Portlandia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Myth of Portlandia

Portland State University PDXScholar Institute of Portland Metropolitan Studies Publications Institute of Portland Metropolitan Studies Winter 2013 The Myth of Portlandia Sara Gates Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/metropolitianstudies Part of the Television Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Gates, S. (2013) The Myth of Portlandia. Winter 2013 Metroscape, p. 24-29. This Article is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Institute of Portland Metropolitan Studies Publications by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. The Myth of Portlandia Portlandia, Grimm, Leverage An interview with Carl Abbott and Karin Magaldi by Sara Gates arl Abbott is a professor of Urban Studies and Planning at Portland State C University and a local expert on the intertwining relationships between the growth, urbanization, and cultural evolutions of cities. Since beginning his tenure at PSU in 1978, Dr. Abbott has published numerous books on Portland itself, as well as the urbanization of the American West; his most recent is Portland in Three Centuries: The Place and the People (2011). Karin Magaldi is the department chair of Theatre & Film at PSU, with extensive experience in teaching screenwriting and production. In addition to directing several PSU departmental productions, she has also worked with local theatre groups including Portland Center Stage, Third Rail Repertory, and Artists Repertory Theatre. Recently, Metroscape writer Sara Gates sat down with Dr. -

Television Academy Awards

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Music Composition For A Series (Original Dramatic Score) The Alienist: Angel Of Darkness Belly Of The Beast After the horrific murder of a Lying-In Hospital employee, the team are now hot on the heels of the murderer. Sara enlists the help of Joanna to tail their prime suspect. Sara, Kreizler and Moore try and put the pieces together. Bobby Krlic, Composer All Creatures Great And Small (MASTERPIECE) Episode 1 James Herriot interviews for a job with harried Yorkshire veterinarian Siegfried Farnon. His first day is full of surprises. Alexandra Harwood, Composer American Dad! 300 It’s the 300th episode of American Dad! The Smiths reminisce about the funniest thing that has ever happened to them in order to complete the application for a TV gameshow. Walter Murphy, Composer American Dad! The Last Ride Of The Dodge City Rambler The Smiths take the Dodge City Rambler train to visit Francine’s Aunt Karen in Dodge City, Kansas. Joel McNeely, Composer American Gods Conscience Of The King Despite his past following him to Lakeside, Shadow makes himself at home and builds relationships with the town’s residents. Laura and Salim continue to hunt for Wednesday, who attempts one final gambit to win over Demeter. Andrew Lockington, Composer Archer Best Friends Archer is head over heels for his new valet, Aleister. Will Archer do Aleister’s recommended rehabilitation exercises or just eat himself to death? JG Thirwell, Composer Away Go As the mission launches, Emma finds her mettle as commander tested by an onboard accident, a divided crew and a family emergency back on Earth. -

Netflix's Big Mouth

Netflix’s Big Mouth Big Mouth = Big Topics The first season of Netflix’s new animated show Big Mouth debuted on September 29, 2017 and is very popular among teens and young adults. Boasting an all-star cast and a 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, the cartoon is about middle schoolers going through puberty in the most explicit, perverse, and, at times, depraved way possible. Puberty is indeed a difficult time for all of us, and while the show does bring some good to the discussion, it’s also fraught with problems. What do I need to know about Big Mouth? It’s an adult cartoon based on the real-life experiences that comic writers Nick Kroll and An- drew Goldberg had as kids growing up in New York. They share, in graphic detail, what it was like growing up and going through puberty. As most young men do, Nick and Andrew strug- gled through lust, sexuality, relationships with girls, and the ups and downs of friendship. The show features some of the most popular comedians of our time as the voices, including: John Mulaney, Fred Armisen, Kristen Wiig, and Jordan Peele. Although the show is about pre-teens, it is intended for an adult audience. However, Netflix does not effectively limit younger viewers’ access, and undoubtedly, there will be many teens and pre-teens who watch the show. Many of them have lots of questions about sex, and they will be drawn to the show in hopes of finding answers. Unfortunately, due to the content, they are likely to develop some severely warped ideas from watching it. -

Kyle Maclachlan

KYLE MACLACHLAN ACCLAIMED ACTOR KYLE MACLACHLAN has brought indelible charm and a quirky sophistication to some of film and television’s most memorable roles. Since 2005, MacLachlan has channeled his strong interest in the world of wine into a second, equally satisfying professional pursuit. A native of Yaki- ma, Wash., located in the heart of the Columbia Valley wine appellation MacLachlan has produced three highly-rated Columbia Valley wines: Pursued by Bear Cabernet Sauvignon, Baby Bear Syrah and his most recent, Blushing Bear Rosé. What began as an unabashed love for his home state and a desire to stay connected to his family roots has become a true passion and dedication to the craft of winemaking. MacLachlan has be- come an advocate and evangelist for the unique properties and flavor profile of Washington state wines. He is personally involved in every aspect of Pursued by Bear wines. MacLachlan sees a connection between acting and winemaking in terms of the combination and balance of process, patience and creativity. He chose to call his wine Pursued by Bear as an homage to perhaps the most famous of all stage directions, “exit, pursued by bear,” from Act III, scene iii of Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale. It’s a funny and unexpected phrase that’s not only a nod to his theatrical roots but also plays to his sense of humor. “It just seemed to fit what I was trying to do,” he said. MacLachlan is perhaps best known for his performance as FBI Special Agent Dale Cooper in David Lynch’s ground-breaking series Twin Peaks, for which he received two Emmy nominations and a Golden Globe Award. -

Film Financing

2017 An Outsider’s Glimpse into Filmmaking AN EXPLORATION ON RECENT OREGON FILM & TV PROJECTS BY THEO FRIEDMAN ! ! Page | !1 Contents Tracktown (2016) .......................................................................................................................6 The Benefits of Gusbandry (2016- ) .........................................................................................8 Portlandia (2011- ) .....................................................................................................................9 The Haunting of Sunshine Girl (2010- ) ...................................................................................10 Green Room (2015) & I Don’t Feel at Home in This World Anymore (2017) ...........................11 Network & Experience ............................................................................................................12 Financing .................................................................................................................................12 Filming ....................................................................................................................................13 Distribution ...............................................................................................................................13 In Conclusion ...........................................................................................................................13 Financing Terms .....................................................................................................................15 -

Hunger Makes Me a Modern Girl: a Memoir Free

FREE HUNGER MAKES ME A MODERN GIRL: A MEMOIR PDF Carrie Brownstein | 256 pages | 05 Nov 2015 | Little, Brown Book Group | 9780349007922 | English | London, United Kingdom Hunger Makes Me a Modern Girl by Carrie Brownstein: | : Books Look Inside. Oct 27, Minutes Buy. Before Carrie Brownstein became a music icon, she was a young girl growing up in the Pacific Northwest just as it was becoming the setting for one the most important movements in rock history. Seeking a sense of home and identity, she would discover both while moving from spectator to creator in experiencing the power and mystery of a live performance. With Sleater-Kinney, Brownstein and her bandmates rose to prominence in the burgeoning underground feminist punk-rock movement that would define music and pop culture in the s. With deft, lucid prose Brownstein proves herself as formidable on the page as on the stage. That quality has become obvious over the course of eight albums with bandmates Corin Tucker and Janet Weiss… and now in her refreshingly forthright new memoir, Hunger Makes Me a Modern Girl. Instead, she candidly recounts the panic attacks and stress-induced shingles she experienced on tour. More important, it shows how compelling she is when she opens up. She carries a lot of humor and gentle self-deprecation throughout the work. For Carrie Brownstein, who grew up in the Riot Grrrl movement in the Pacific Northwest, they did: She started out playing in countless punk bands until settling on one with her BFF and romantic partner, Corin Tucker, which they eventually turned into the best rock band of all time, Sleater-Kinney. -

The Hawthorne PDX

MULTI-FAMILY The Hawthorne PDX 4717 SE HAWTHORNE BLVD. PORTLAND, OR 97214 PROPERTY - AT A GLANCE Lot Size Building Size 16,500 SQ FT 38,401 SQ FT # of Units Completion Date 50 July 2015 Lender Architect BANK OF THE LRS WEST General Developer Contractor EASTBANK PATH PDX FEATURED AMENITIES Community Lounge AC/ Heat in Select Homes City Views _____ _____ _____ 9 Foot Ceilings Extra Large Closets Rooftop Terrace _____ _____ _____ Large Industrial Loft Style Excellent nearby dining and Bike Storage Windows nightlife _____ _____ _____ Controlled Access Building Full sized washer and dryer in Near Mt. Tabor Park _____ every home _____ _____ Pet Grooming Station Easy AccessBus Lines _____ Stainless Appliances _____ _____ Parking Garage Quartz Counter-tops The Hawthorne PDX CREATIVE APARTMENTS IN THE ICONIC HAW THORNE DISTRIC T The Hawthorne PDX is a 50-unit mid-rise apartment 360-degree views of downtown and Mt. Tabor. A Portland building with ground floor retail located on Portland’s Ice Cream Staple, Ruby Jewel, is located on the ground eclectic Hawthorne Boulevard. The homes have a striking floor wafting the fresh scent of waffle cones throughout the contrast of rich wood tones and bright white walls lit by building. Predominantly comprised of urban one bedrooms sun drenched windows. Residents enjoy perfectly curated and walk-though one bedrooms, The Hawthorne offers amenities including a pet wash, barbecue area, bike residents organic, flowing space to utilize in a way that best storage, off-street parking, a community gathering space suits their creative lifestyle. and rooftop terrace with LOCATION HIGHLIGHTS Portland’s Hawthorne District is reminiscent of the 1960s and was at the forefront of Portland hippie movement. -

The Creative Life of 'Saturday Night Live' Which Season Was the Most Original? and Does It Matter?

THE PAGES A sampling of the obsessive pop-culture coverage you’ll find at vulture.com ost snl viewers have no doubt THE CREATIVE LIFE OF ‘SATURDAY experienced Repetitive-Sketch Syndrome—that uncanny feeling NIGHT LIVE’ WHICH Mthat you’re watching a character or setup you’ve seen a zillion times SEASON WAS THE MOST ORIGINAL? before. As each new season unfolds, the AND DOES IT MATTER? sense of déjà vu progresses from being by john sellers 73.9% most percentage of inspired (A) original sketches season! (D) 06 (B) (G) 62.0% (F) (E) (H) (C) 01 1980–81 55.8% SEASON OF: Rocket Report, Vicki the Valley 51.9% (I) Girl. ANALYSIS: Enter 12 51.3% new producer Jean Doumanian, exit every 08 Conehead, Nerd, and 16 1975–76 sign of humor. The least- 1986–87 SEASON OF: Samurai, repetitive season ever, it SEASON OF: Church Killer Bees. ANALYSIS: taught us that if the only Lady, The Liar. Groundbreaking? breakout recurring ANALYSIS: Michaels Absolutely. Hilarious? returned in season 11, 1990–91 character is an unfunny 1982–83 Quite often. But man-child named Paulie dumped Billy Crystal SEASON OF: Wayne’s SEASON OF: Mr. Robinson’s unbridled nostalgia for Herman, you’ve got and Martin Short, and Neighborhood, The World, Hans and Franz. SNL’s debut season— problems that can only rebuilt with SNL’s ANALYSIS: Even though Whiners. ANALYSIS: Using the second-least- be fixed by, well, more broadest ensemble yet. seasons 4 and 6 as this is one of the most repetitive ever—must 32.0% Eddie Murphy. -

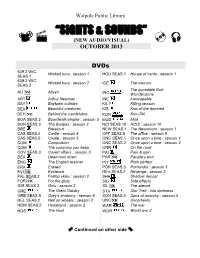

New Audio/Visual) October 2013

Walpole Public Library “SIGHTS & SOUNDS” (NEW AUDIO/VISUAL) OCTOBER 2013 DVDs 639.2 WIC Wicked tuna : season 1 HOU SEAS.1 House of cards : season 1 SEAS.1 639.2 WIC Wicked tuna : season 2 ICE The iceman SEAS.2 The incredible Burt ALI NR Aliyah INC Wonderstone ART Arthur Newman INE Inescapable BAY Baytown outlaws KIL Killing season BEA Beautiful creatures KIS Kiss of the damned BEH NR Behind the candelabra KON Kon-Tiki BOA SEAS.3 Boardwalk empire : season 3 MUD Mud BOR SEAS.3 The Borgias : season 3 NCI SEAS.10 NCIS : season 10 BRE Breakout NEW SEAS.1 The Newsroom : season 1 CAS SEAS.4 Castle : season 4 OFF SEAS.9 The office : season 9 CAS SEAS.5 Castle : season 5 ONC SEAS.1 Once upon a time : season 1 COM Compulsion ONC SEAS.2 Once upon a time : season 2 COM The company you keep ONR On the road COV SEAS.3 Covert affairs : season 3 PAI Pain & gain DEA Dead man down PAR NR Parade’s end ENG The English teacher PIT Pitch perfect ERA Erased POR SEAS.3 Portlandia : season 3 EVI NR Evidence REV SEAS.2 Revenge : season 2 FAL SEAS.2 Falling skies : season 2 SHA Shadow dancer FOR NR For the glory SID Side effects GIR SEAS.2 Girls : season 2 SIL NR The silence GRE The Great Gatsby STA Star Trek : into darkness GRE SEAS.9 Grey’s anatomy : season 9 SON SEAS.5 Sons of anarchy : season 5 HEL SEAS.2 Hell on wheels : season 2 UNC NR Uncertainty HOM SEAS.2 Homeland : season 2 WAR The war HOS The Host WOR World war Z Continued on other side 2 Walpole Public Library NEW AUDIO/VISUAL 2013 Books on CD Manson : the life and Refusal 364.1523 MAN times of -

The Roots Report: an Interview with Aimee Mann

The Roots Report: An Interview with Aimee Mann John Fuzek: Hi, Aimee, how are you? Where are you calling from? Aimee Mann: Good, I am in Los Angeles. JF: Are you currently on tour or home? AM: I am at home for a couple of weeks, we’re going back out on the 19th JF: How long will you be out on the road? AM: This time I think it’s just a few weeks. JF: So, you live in LA? AM: Yes JF: Does being in LA help you get involved with film work as well as music? AM: You know I think there is a thing that living in LA, it helps just being around, there are certain things where you just run into people or seeing someone at a party and they have a project, it’s more likely that they think of you than somebody that they haven’t seen for a long time, I think there’s a weird causal effect that helps JF: Is that how you wound up playing a maid in Portlandia? AM: Yeah, well, I’ve known Fred Armisen for a long time, he lived out here, i knew him from the Largo Comedy scene, there’s a comedy club out here called Cafe Largo and um, before he was on Saturday Night Live, so, yeah, we’ve been friends for a long time, I did meet him out here. JF: Do you have any projects like that coming up or do they just pop up randomly? AM: There’s a new Comedy Central TV show, I don’t think it will be out until next year, called Anton Deville (somewhat inaudible ?) and I have a part, I am in one of those, it’s fun to get calls for that stuff JF: Are you still married to Michael Penn? AM: Yes JF: How come I never really hear about his music anymore? AM: He’s not into performing, it’s not his thing, he does a lot of scoring, he scored The Girls TV show and Masters Of Sex, he likes to be more behind the scenes. -

BRYCE FORTNER Director of Photography Brycefortner.Com

BRYCE FORTNER Director of Photography brycefortner.com PROJECTS Partial List DIRECTORS STUDIOS/PRODUCERS A MILLION LITTLE THINGS James Griffiths KAPITAL ENTERTAINMENT / ABC Pilot & Season 4 Various Directors Chris Smirnoff, DJ Nash Aaron Kaplan STARGIRL 2 Julia Hart GOTHAM GROUP / DISNEY+ Feature Film Nathan Kelly, Jordan Horowitz Ellen Goldsmith-Vein HELLO, GOODBYE AND EVERYTHING Michael Lewen ACE ENTERTAINMENT IN BETWEEN Feature Film Chris Foss, Max Siemers I’M YOUR WOMAN Julia Hart AMAZON Feature Film Jordan Horowitz, Rachel Brosnahan STARGIRL Julia Hart GOTHAM GROUP / PRINCIPAL DISNEY Feature Film Jim Powers, Jordan Horowitz DOLLFACE Matt Spicer ABC SIGNATURE / HULU Pilot Melanie Elin, Stephanie Laing BROKEN DIAMONDS Peter Sattler BLACK LABEL Feature Film Ellen Schwartz, Mary Sparacio THE MAYOR James Griffiths ABC Pilot Scott Printz, Jean Hester PROFESSOR MARSTON & THE Angela Robinson SONY WONDER WOMEN Terry Leonard, Amy Redford Feature Film Andrea Sperling, Jill Soloway THE TICK Wally Pfister SONY / AMAZON Pilot Kerry Orent, Barry Josephson INGRID GOES WEST Feature Film Matt Spicer STAR THROWER ENTERTAINMENT Official Selection, Sundance Film Festival Jared Goldman HOUSE OF CARDS Wally Pfister NETFLIX Season 4 Promos CHARITY CASE James Griffiths ABC / FOX Pilot Scott Printz, Thea Mann PUNCHING HENRY Feature Film Gregori Viens Ian Coyne, David Permut Official Selection, SXSW Film Festival FLAKED Wally Pfister NETFLIX Series Josh Gordon Tiffany Moore, Mitch Hurwitz Will Arnett TOO LEGIT Short Frankie Shaw Liz Destro Official Selection, -

Live Wire Radio Pacific Northwest Friends: $2,500 to $4,999

LIVE WIRE SPONSORSHIP DECK 2020 AN INCREDIBLE PARTNERSHIP ON-THE-AIR WITH LIVE WIRE High-Quality, Engaged, Clutter-Free & National & Distinctive Influential & Trusted Multi-Channel Programming Culturally-Minded Messaging Opportunities Audience Platform LIVE WIRE IT’S LATE NIGHT FOR RADIO Hosted by Luke Burbank, Live Wire combines the prestige of national radio broadcasting with its own outstanding reputation as an independently-produced Portland production. Over the last 16 years, Live Wire has brought audiences together to spark moments of human connectedness through performance, humor, and unpredictable moments of discovery. Live Wire is music, comedy, and conversation. Our show stands out as one of the fastest growing entertainment radio programs on air today. Listeners turn to Live Wire every week to laugh, learn, and feel the nation’s cultural pulse. It’s Late Night for Radio. THE VOICES OF LIVE WIRE FEATURED GUESTS MUSIC: Jeff Tweedy, Pink Martini, Melissa Etheridge, Little Freddie King, Patterson Hood, Kishi Bashi, Mandy Moore, Thundercat, Shakey Graves, Neko Case, Shovels & Rope, Thao and the Get Down Stay Down, Loudon Wainwright III, Waxahatchee, Blitzen Trapper, Amythyst Kiah, and Reggie Watts HOST LUKE COMEDY: Abbi Jacobson, Janeane Garofalo, Marc BURBANK Maron, Phoebe Robinson, John Hodgman, Hari Kondabolu, Paula Poundstone, Thomas Middleditch, Luke Burbank grew up one of seven Ben Schwartz, Reggie Watts, Mo Rocca, Kristen kids, learning early on how to vie for Schaal, Carrie Brownstein, and Fred Armisen attention. Those profound childhood issues have propelled him to contribute to and create various media projects, CONVERSATION: Salman Rushdie, W. Kamau Bell, including Wait Wait...Don’t Tell Me, This Lindy West, Jesse Eisenberg, Ijeoma Oluo, John Irving, American Life, CBS Sunday Morning, Diana Nyad, Eileen Myles, Jonathan Safran Foer, Luis and the daily podcast Too Beautiful to Live.