In Front of the Camera, Behind the Camera: Ullmann Directs Bergman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Films of Ingmar Bergman: Centennial Celebration!

The Films of Ingmar Bergman: Centennial Celebration! Swedish filmmaker, author, and film director Ingmar Bergman was born in 1918, so this year will be celebrated in Sweden and around the world by those who have been captivated by his work. Bergman belongs to a group of filmmakers who were hailed as "auteurs" (authors) in the 1960s by French, then American film critics, and his work was part of a wave of "art cinema," a form that elevated "movies" to "films." In this course we will analyze in detail six films by Bergman and read short pieces by Bergman and scholars. We will discuss the concept of film authorship, Bergman's life and work, and his cinematic world. Note: some of the films to be screened contain emotionally or physically disturbing content. The films listed below should be viewed BEFORE the scheduled OLLI class. All films will be screened at the PFA Osher Theater on Wednesdays at 3-5pm, the day before the class lecture on that film. Screenings are open to the public for the usual PFA admission. All films are also available in DVD format (for purchase on Amazon and other outlets or often at libraries) or on- line through such services as FilmStruck (https://www.filmstruck.com/us/) or, in some cases, on YouTube (not as reliable). Films Week 1: 9/27 Wild Strawberries (1957, 91 mins) NOTE: screening at PFA Weds 9/25 Week 2: 10/4 The Virgin Spring (1960, 89 mins) Week 3: 10/11 Winter Light (1963, 80 mins) Week 4: 10/18 The Silence (1963, 95 mins) Week 5: 10/25 Persona (1966, 85 mins) Week 6: 11/1 Hour of the Wolf (1968, 90 mins) -

50Th Chicago International Film Festival to Open with Liv Ullmann's Torrid Adaptation of August Strindberg Play “Miss Julie”

[Type text] [Type text] [Type text] Media Contacts: Alejandro Riera Nick Harkin/Carly Leviton 312.683.0121, x. 116 Carol Fox and Associates [email protected] 773.327.3830 x 103/104 [email protected] [email protected] 50TH CHICAGO INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL TO OPEN WITH LIV ULLMANN'S TORRID ADAPTATION OF AUGUST STRINDBERG PLAY “MISS JULIE” Oct. 9 Festival Opener Stars Jessica Chastain and Colin Farrell CHICAGO, IL (September 9, 2014) –The 50th Chicago International Film Festival (October 9- 23, 2014) announces the selection of “Miss Julie,” directed by veteran actress and Ingmar Bergman collaborator Liv Ullmann and starring Golden Globe®-award winning actors Jessica Chastain, Colin Farrell and Samantha Morton as its Opening Night film. “Miss Julie” will screen October 9 at the Harris Theater (205 E. Randolph Dr.). The red carpet event starts at 6 p.m. Director Liv Ullmann is scheduled to attend. Based on August Strindberg’s 1888 groundbreaking naturalistic drama, “Miss Julie” takes place over the course of one midsummer night in an Irish country estate, as the haughty Miss Julie (Jessica Chastain) and her father's lowly valet John (Colin Farrell) charm and manipulate each other. By turns seductive and bullying, savage and tender, their intimate relationship leads to a desperate plan, culminating in a final act as sublime and devastating as anything in Greek tragedy. Ullmann brings renewed vitality to August Strindberg’s classic play of power, class and seduction. “Since her extraordinary directorial debut, ‘Sofie,’ in 1992, we have premiered each and every one of Liv’s directorial efforts,” said Chicago International Film Festival Founder and Artistic Director Michael Kutza. -

Karin Franz Körlof + the Nile Hilton Incident, a Hustler’S Diary, up in the Sky and Much More

Issue 1 • 2017 SHOOTING STAR Karin Franz Körlof + The Nile Hilton Incident, A Hustler’s Diary, Up in the Sky and much more A magazine from the Swedish Film Institute • sfi.se 25 years Welcome 1 000 co-productions Head of International Pia Lundberg Film i Väst 1992–2017 www.fi lmivast.com Phone: +46 70 692 79 80 [email protected] Festivals, features Petter Mattsson Phone +46 70 607 11 34 Film i Väst congratulates [email protected] its co-productions in Berlin! Festivals, documentaries Sara Rüster A fresh start Phone: +46 76 117 26 78 [email protected] Panta rhei. All things are in flux. They A Hustler’s Diary, a dramedy where a certainly are, and Sweden and the Swedish suburban small-time criminal clashes film industry is no exception. At the time with his past and the very elite of Stock- Festivals, shorts Theo Tsappos of writing we are only weeks into a new holm’s cultural life. We have Sami Blood Phone: +46 76 779 11 33 national film policy. We see it as a chance in Berlin and the TV series Midnight Sun [email protected] to go through the old film funding that’s in Rotterdam – and they both, in com- been around for decades, modernize it – pletely different ways, tell a story about and start afresh. We’re going cherry-pick- the Sami minority. Those are just a few Special projects ing, taking what’s worked for us and other examples of Swedish films that are Josefina Mothander countries before, and putting the pieces selected for various festivals in the first Phone +46 70 972 93 52 together to build something new. -

Det Handlar Omatt Lyfta Varann

NUMMER 2/2014 Barn- morskor hann inte läsa patient- journaler Lena Endre: Det handlar om att lyfta varann Vänstern EU-valet påverkar Möt Karlstads Solidaritet med i Gävle har Sverige mer än mest poetiska Grekland. Mer fördubblats. de flesta vet om. sotare. om insamlingen. EN TIDNING FRÅN VÄNSTERPARTIET EN TIDNING FRÅN VÄNSTERPARTIET, NR 2/2014 Kalle LarssonKalle Görgen Persson Görgen 24 Garcia Losita 10 18 Dags att välja Gävle växer Hur står det till? EUs nyliberala politik För två år sedan startade Varför saknas det barnmorskor orsakar kris i Europa. Men Vänsterpartiet Gävle upp sina och förlossningsplatser Vänsterpartiet vill gå en annan Röda Lördagar och Öppna på så många orter? väg. Välfärden kan räddas – torsdagar. Det har inte gått bra, RÖTT tog pulsen på både här hemma och i EU, det har gått över förväntan! Skånes Universitetssjukhus’ säger Malin Björk, V. Ändå är det ganska enkelt… förlossningsavdelning. Inte en enda gång hörde jag dem säga någonting om vad de gjorde inne på Metallen i Finspång. Lennart Lundquist, Krönikan sidan 15. 34 & 39 Eskilstuna 17 Valfordon? 14 Läkerol och Kalmar kan Plus: Kostar obe Läkerolfabriken har Både i Kalmar tydligt mer än en försörjt många famil 16 Bara RÖTT Landsting och i valstuga, kan flyttas jer genom åren. RÖTT rekommen Eskilstuna kommun snabbt, syns bra, lätt I hundra år faktiskt. derar tre intressanta har V fått igenom att få bemannad. Sedan kom en risk poddar. En, Lilla vänster politik utan Minus: Drivmedlet. kapitalist och köpte drevet, med skratt att vara särskilt stora. Vi pratar brandbil. upp den. garanti. Rött utges av Vänsterpartiet. -

The Films of Ingmar Bergman Jesse Kalin Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521380650 - The Films of Ingmar Bergman Jesse Kalin Frontmatter More information The Films of Ingmar Bergman This volume provides a concise overview of the career of one of the modern masters of world cinema. Jesse Kalin defines Bergman’s conception of the human condition as a struggle to find meaning in life as it is played out. For Bergman, meaning is achieved independently of any moral absolute and is the result of a process of self-examination. Six existential themes are explored repeatedly in Bergman’s films: judgment, abandonment, suffering, shame, a visionary picture, and above all, turning toward or away from others. Kalin examines how Bergman develops these themes cinematically, through close analysis of eight films: well-known favorites such as Wild Strawberries, The Seventh Seal, Smiles of a Summer Night, and Fanny and Alexander; and im- portant but lesser-known works, such as Naked Night, Shame, Cries and Whispers, and Scenes from a Marriage. Jesse Kalin is Andrew W. Mellon Professor of Humanities and Professor of Philosophy at Vassar College, where he has taught since 1971. He served as the Associate Editor of the journal Philosophy and Literature, and has con- tributed to journals such as Ethics, American Philosophical Quarterly, and Philosophical Studies. © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521380650 - The Films of Ingmar Bergman Jesse Kalin Frontmatter More information CAMBRIDGE FILM CLASSICS General Editor: Ray Carney, Boston University The Cambridge Film Classics series provides a forum for revisionist studies of the classic works of the cinematic canon from the perspective of the “new auterism,” which recognizes that films emerge from a complex interaction of bureaucratic, technological, intellectual, cultural, and personal forces. -

SVT World Jul Nyar 2014 2015.Pdf

Kultur, musik & nöje Aje Aje Mellin/SVT Knut Koivisto/SVT Koivisto/SVT Knut - © Björk/SVT Bo Tack för musiken Kim Anderzon till minne © Niklas Strömstedt är tillbaka som programledare och Två program till minne av nyligen bortgångna artisten träffar några av Sveriges absolut största och Kim Anderzon. Det första är en intervju som Anja folkkäraste artister. Vi får njuta av massor med skön Kontor gjorde när Kim Anderzon firade 30 år som musik, anekdoter och minnen. artist. Det andra är en kvinnofest från Cirkus i SVT World fre 12 dec kl 21.00 CET: Jill Johnson Stockholm där Kim Anderzon och Lottie Ejebrand är SVT World fre 19 dec kl 21.00 CET: Peter Jöback programledare. Bland de medverkande finns bl a SVT World fre 26 dec kl 22.00 CET: Sarah Dawn Margaretha Krook, Monica Zetterlund, Monica Finer Dominique och Stina Ekblad. SVT World fre 2 jan kl 21.00 CET: Mauro Scocco SVT World mån 22 dec kl 12.00 CET: Personligt SVT World mån 22 dec kl 23.15 CET: Kvinnofest En sång om glädje i juletid Nils Börge Gårdh återkommer även i år med folkkära artister som framför några av våra käraste julsånger tillsammans med kören Masters Voice. Med Sonja Aldén, Magnus Carlsson, Dogge Dogelito, Evelina Gard, Tommy Nilsson och Jan Johansen. SVT World mån 22 dec kl 18.15 CET - 1:2 SVT World tis 23 dec kl 23.15 CET - 2:2 SVT Foto: Mats Ek och Julia & Romeo I den publik- och kritikerhyllade dansföreställningen Julia och Romeo vänder koreografen Mats Ek på perspektivet och berättar historien utifrån Julias perspektiv. -

The Life and Films of the Last Great European Director

Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 INGMAR BERGMAN Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 19, 2009 11:55 Geoffrey Macnab writes on film for the Guardian, the Independent and Screen International. He is the author of The Making of Taxi Driver (2006), Key Moments in Cinema (2001), Searching for Stars: Stardom and Screenwriting in British Cinema (2000), and J. Arthur Rank and the British Film Industry (1993). Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 INGMAR BERGMAN The Life and Films of the Last Great European Director Geoffrey Macnab Macnab-05480001 macn5480001_fm May 8, 2009 9:23 Sheila Whitaker: Advisory Editor Published in 2009 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 www.ibtauris.com Distributed in the United States and Canada Exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 Copyright © 2009 Geoffrey Macnab The right of Geoffrey Macnab to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978 1 84885 046 0 A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress -

Berlin /Filmart 2020

BERLIN /FILMART 2020 HOPE HOPE 4-5 DO NOT HESITATE 22-23 MONTY AND THE STREET PARTY 6-7 NINJABABY 24-25 LINE-UP CHARTER 8-9 A TASTE OF HUNGER 26-27 MORTAL 10-11 MY FATHER MARIANNE 28-29 THE TUNNEL 12-13 RIDERS OF JUSTICE 30-31 BREAKING SURFACE 14-15 THE NORTH SEA 32-33 THE CROSSING 16-17 THE MARCO EFFECT 34-35 ANOTHER ROUND 18-19 RECENT TITLES 36-37 SCREENING SCHEDULE 38 BETRAYED 20-21 CONTACTS 39 INDEX PANORAMA HOPE - Directed by Maria Sødahl Following a successful world premiere in the Discovery Section at Toronto International Film Festival, HOPE now makes its European debut on one of the most prestigious festival scenes in the world; the Berlinale. Selected for the Panorama Section, European audiences will get the chance to see the second feature by Maria Sødahl which has taken international as well as local critics by storm. Based on Sødahl’s own personal story and featuring actress Andrea Bræin Hovig (AN AFFAIR, 2018) and award-winning actor Stellan Skarsgård (CHERNOBYL, 2019; NYMPHOMANIAC, 2013; MELANCHOLIA, 2011), this heartrending drama takes us on a beautiful journey through the many aspects of life, love and the fear of losing. Sødahl had her breakthrough with her debut film LIMBO (2010), which won several awards and was highly acknowledged at international film festivals. What happens with love when a woman in the middle of her life gets three months left to live? Anja (43) lives with Tomas (59) in a large family of biological children and stepchildren. For years, the couple PRESS SCREENING have grown independent of each other. -

Swedish Film Magazine #1 2009

Swedish Film IN THE MOOD FOR LUKAS Lukas Moodysson’s Mammoth ready to meet the world Nine more Swedish films at the Berlinale BURROWING | MR GOVERNOR THE EAGLE HUNTEr’s SON | GLOWING STARS HAVET | SLAVES | MAMMA MOO AND CROW SPOT AND SPLODGE IN SNOWSTORM | THE GIRL #1 2009 A magazine from the Swedish Film Institute www.sfi.se Fellow Designers Internationale Filmfestspiele 59 Berlin 05.–15.02.09 BERLIN INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL 2009 OFFICIAL SELECTION IN COMPETITION GAEL GARCÍA BERNAL MICHELLE WILLIAMS MA FILMA BYM LUKMAS MOOODTYSSHON MEMFIS FILM COLLECTION PRODUCED BY MEMFIS FILM RIGHTS 6 AB IN CO-PRODUCTION WITH ZENTROPA ENTERTAINMENTS5 APS, ZENTROPA ENTERTAINMENTS BERLIN GMBH ALSO IN CO-PRODUCTION WITH FILM I VÄST, SVERIGES TELEVISION AB (SVT), TV2 DENMARK SUPPORTED BY SWEDISH FILM INSTITUTE / COLLECTION BOX / SINGLE DISC / IN STORES 2009 PETER “PIODOR” GUSTAFSSON, EURIMAGES, NORDIC FILM & TV FUND/HANNE PALMQUIST, FFA FILMFÖRDERUNGSANSTALT, MEDIENBOARD BERLIN-BRANDENBURG GMBH, DANISH FILM INSTITUTE/ LENA HANSSON-VARHEGYI, THE MEDIA PROGRAMME OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITY Fellow Designers Internationale Filmfestspiele 59 Berlin 05.–15.02.09 BERLIN INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL 2009 OFFICIAL SELECTION IN COMPETITION GAEL GARCÍA BERNAL MICHELLE WILLIAMS MA FILMA BYM LUKMAS MOOODTYSSHON MEMFIS FILM COLLECTION PRODUCED BY MEMFIS FILM RIGHTS 6 AB IN CO-PRODUCTION WITH ZENTROPA ENTERTAINMENTS5 APS, ZENTROPA ENTERTAINMENTS BERLIN GMBH ALSO IN CO-PRODUCTION WITH FILM I VÄST, SVERIGES TELEVISION AB (SVT), TV2 DENMARK SUPPORTED BY SWEDISH FILM INSTITUTE -

Timeline of Selected Bergman 100 Events

London, 18.09.17 Timeline of selected Bergman 100 events This timeline includes major activities before and during the Bergman year. Please note that there are many more events to be announced both within this timeframe and beyond. A full, regularly updated calendar of performances, retrospectives, exhibitions and other events is available at www.ingmarbergman.se September 2017 • Misc.: Launch of Bergman 100, 18 Sep, London, UK. • On stage: Scenes from a marriage, opening 31 Aug, Det Kgl Teater (The Royal Playhouse), Copenhagen, Denmark. • On stage: Autumn Sonata (opera), opening 8 Sep, Finnish National Opera, Helsinki, Finland. • Book release: Ingmar Bergman A–Ö (in English), Ingmar Bergman Foundation/Norstedts publishing, Sweden. • On stage: The Best Intentions, opening 16 Sep, Aarhus theatre, Aarhus, Denmark. • On stage: After the Rehearsal/Persona, The Barbican, London, UK. • On stage: Scenes From a Marriage, opening 20 Sep, Teatros del Canal, Madrid, Spain. • On stage: Breathe, Bergman-inspired dance performance, opening 28 Sep, Inkonst, Malmö, Sweden. • On stage: The Serpent’s Egg, opening 30 Sep, Cuvilliés-Theater, Munich, Germany. • On stage: Scenes From a Marriage, world tour Sep–Dec, Asia, Europe, South America. October 2017 • On stage: Scenes from a marriage, opening 5 Oct, Ernst-Deutsch-Theater, Hamburg, Germany. • On stage: After the rehearsal, opening 20 Oct, Düsseldorfer Schauspielhaus, Düsseldorf, Germany. • Misc.: The European Film Academy awards Hovs Hallar the title ‘Treasure of European Film Culture’. (A nature reserve in the county of Skåne, Sweden, Hovs Hallar is the location of the chess scene in The Seventh Seal.) • On stage: Scenes From a Marriage, opening 25 Oct, Teatro Tivoli, Barcelona, Spain. -

For Ingmar Bergman, Uppsala Was the Place of Childhood Uppsala Ist Für Ingmar Bergman Ein Ort Der Kindheitserinnerungen

For Ingmar Bergman, Uppsala was the place of childhood Uppsala ist für Ingmar Bergman ein Ort der Kindheitserinnerungen. Akademikvarnen [ 3 ] an dem Flüsschen Fyrisån als Bischofshaus, Steinwurf von der Domkyrkan [ 2 ], dem Schloß [ 6 ] und nicht zuletzt als auch die Wirklichkeit abgewandelt.) Das Uppsala stadshotell lag Bergmans Uppsala ist weniger ein geographischer Ort, sondern Der Epilog des Buches ist eigentlich ein Prolog, da sich das Gespräch, UPPSALA memories. This is where he was born, and although his In Uppsala ist er zur Welt gekommen, und auch als die Familie deren Räumlichkeiten heute vom Museum Upplandsmuseet genutzt dem Kino Slottsbiografen [ 7 ] entfernt. wirklich dort, ist aber inzwischen geschlossen. vielmehr eine Welt aus Kindertagen, die zum Mythos erhoben wird. welches dort stattfindet, bereits vor dem Rest der Handlung zugetragen family moved to Stockholm not long after his birth, he kurz darauf nach Stockholm zog, verbrachte er viel Zeit bei seiner werden. Das rauschende Wasser des Flusses ist ein Leitmotiv, das hat. Anna und ihr Konfirmationspastor Jacob führen dieses Gespräch; Zeit, die verstreicht, Glocken, die schlagen und Uhren, die ticken, Ebenso wenig wie es jemals Märtas Matsalar gegeben hat, ist auch der spent a great deal of time at his maternal grandmother’s in Großmutter in Uppsala. Die Stadt nimmt in Ingmar Bergmans Werk den gesamten Film durchzieht. sie setzen sich auf eine Bank vor der Kirche, über die Jacob folgendes Uppsala är för Ingmar Bergman barndomens och minnenas Uppsala. Appearing in his work as of a sort of Arcadia, a die Bedeutung eines Arkadien, einer verlorenen Welt ein und spielt Die besten Absichten gehören in Bergmans Filmen und Büchern zum Inventar: „Die Kastanien Ort, an dem die Auseinandersetzung zwischen den Rivalinnen Anna zu berichten weiß: „Weißt du, daß die Trefaldighet-Kirche ursrprünglich ort. -

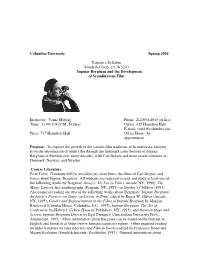

Columbia University Spring 2004 Tentative Syllabus Swedish-Comp

Columbia University Spring 2004 Tentative Syllabus Swedish-Comp. Lit. W3270 Ingmar Bergman and the Development of Scandinavian Film Instructor: Verne Moberg Phone: 212/854-4015 (office) Time: 11:00-3:00 P.M., Fridays Office: 415 Hamilton Hall E-mail: [email protected] Place: 717 Hamilton Hall Office Hours: by appointment Purpose: To explore the growth of the various film traditions in Scandinavia, ranging from the introduction of silent film through the landmark contributions of Ingmar Bergman in Sweden over many decades, with Carl Dreyer and more recent directors in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. Course Literature Print Texts: Handouts will be available on silent films, the films of Carl Dreyer, and basics about Ingmar Bergman. All students are required to read and study at least one of the following works by Bergman: Images: My Life in Film ( Arcade, NY, 1990); The Magic Lantern, his autobiography (Penguin, NY, 1987); or Sunday’s Children (1993). Also required reading are two of the following works about Bergman: Ingmar Bergman: An Artist’s Journey--on Stage, on Screen, in Print, edited by Roger W. Oliver (Arcade, NY, 1995); Gender and Representation in the Films of Ingmar Bergman by Marilyn Blackwell (Camden House, Columbia, S.C., 1997); Ingmar Bergman: The Art of Confession, by Hubert I. Cohen (Twayne Publishers, NY, 1993); and Between Stage and Screen: Ingmar Bergman Directs by Egil Törnquist (Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 1995). More information about Bergman can be found on the Internet in English and Swedish at <http://www.hem.passagen.se/vogler>. Other required reading includes handouts on later directors and Film in Sweden edited by Francesco Bono and Maaret Koskinen (Swedish Institute, Stockholm, 1997).