Master Laois

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Castlecomer Plateau

23 The Castlecomer plateau By T. P. Lyng, N.T. HE Castlecomer Plateau is the tableland that is the watershed between the rivers Nore and Barrow. Owing T to the erosion of carboniferous deposits by the Nore and Barrow the Castlecomer highland coincides with the Castle comer or Leinster Coalfield. Down through the ages this highland has been variously known as Gower Laighean (Gabhair Laighean), Slieve Margy (Sliabh mBairrche), Slieve Comer (Sliabh Crumair). Most of it was included within the ancient cantred of Odogh (Ui Duach) later called Ui Broanain. The Normans attempted to convert this cantred into a barony called Bargy from the old tribal name Ui Bairrche. It was, however, difficult territory and the Barony of Bargy never became a reality. The English labelled it the Barony of Odogh but this highland territory continued to be march lands. Such lands were officially termed “ Fasach ” at the close of the 15th century and so the greater part of the Castle comer Plateau became known as the Barony of Fassadinan i.e. Fasach Deighnin, which is translated the “ wi lderness of the river Dinan ” but which officially meant “ the march land of the Dinan.” This no-man’s land that surrounds and hedges in the basin of the Dinan has always been a boundary land. To-day it is the boundary land between counties Kil kenny, Carlow and Laois and between the dioceses of Ossory, Kildare and Leighlin. The Plateau is divided in half by the Dinan-Deen river which flows South-West from Wolfhill to Ardaloo. The rim of the Plateau is a chain of hills averag ing 1,000 ft. -

Laois TASTE Producer Directory

MEET the MAKERS #WelcomeToTASTE #LaoisTASTE #WelcomeToTASTE #LaoisTASTE Aghaboe Farm Foods Product: Handmade baking Main Contact: Niamh Maher Tel: +353 (0)86 062 9088 Email: [email protected] Address: Keelough Glebe, Pike of Rushall, Portlaoise, Co. Laois, Ireland. Aghaboe Farm Foods was set up by Niamh Maher in 2015. From as far back as Niamh can remember, she has always loved baking tasty cakes and treats. Today, Aghaboe Farm Foods has grown into an award-winning artisan bakery. Specialising in traditional handmade baking, Niamh uses only natural ingredients. “Our flavours change with the seasons and where possible we use local ingredients to ensure the highest AWARDS quality and flavour possible”. Our selection includes cakes, GOLD MEDAL WINNER Blas na hÉireann 2019 tarts, muffins & brownies. Aghaboe Farm Foods sell directly BEST IN LAOIS through farmers’ markets and by private orders through Blas na hÉireann 2019 Facebook. “All of our bespoke products are made to order to BEST IN FARMERS’ MARKET suit customer’s needs”. Blas na hÉireann 2019 In 2017 Aghaboe Farm Foods won Silver at Blas na hÉireann, and in 2018 they achieved a Great Taste Award. In 2019 Niamh has once again been successful, winning a Blas na hÉireann award for her Christmas cake. @aghaboefarmfoods @aghaboefarmfoods #WelcomeToTASTE #LaoisTASTE An Sean-Teach www.anseanteach.com Product: Botanical Gins & Cream Liqueurs Main Contact: Brian Brennan / Carla Taylor Tel: +353 (0)87 261 9151 / +353 (0)86 309 5235 Email: [email protected] Address: Aughnacross, Ballinakill, Co. Laois, Ireland. An Sean-Teach, meaning The Old House in Irish, is named after the traditional thatched house on the farm where the business is located in Co. -

Mountmellick Local Area Plan 2012-2018

Mountmellick Local Area Plan 2012-2018 MOUNTMELLICK LOCAL AREA PLAN 2012-2018 Contents VOLUME 1 - WRITTEN STATEMENT Page Laois County Council October 2012 1 Mountmellick Local Area Plan 2012-2018 2 Mountmellick Local Area Plan 2012-2018 Mountmellick Local Area Plan 2012-2018 Contents Page Introduction 5 Adoption of Mountmellick Local area Plan 2012-2018 7 Chapter 1 Strategic Context 13 Chapter 2 Development Strategy 20 Chapter 3 Population Targets, Core Strategy, Housing Land Requirements 22 Chapter 4 Enterprise and Employment 27 Chapter 5 Housing and Social Infrastructure 40 Chapter 6 Transport, Parking and Flood Risk 53 Chapter 7 Physical Infrastructure 63 Chapter 8 Environmental Management 71 Chapter 9 Built Heritage 76 Chapter 10 Natural Heritage 85 Chapter 11 Urban Design and Development Management Standards 93 Chapter 12 Land-Use Zoning 115 3 Mountmellick Local Area Plan 2012-2018 4 Mountmellick Local Area Plan 2012-2018 Introduction Context Mountmellick is an important services and dormitory town located in north County Laois, 23 kms. south-east of Tullamore and 11 kms. north-west of Portlaoise. It lies at the intersection of regional routes R422 and R433 with the National Secondary Route N80. The River Owenass, a tributary of the River Barrow, flows through the town in a south- north trajectory. Population-wise Mountmellick is the third largest town in County Laois, after Portlaoise and Portarlington. According to Census 2006, the recorded population of the town is 4, 069, an increase of 21% [708] on the recorded population of Census 2002 [3,361]. The population growth that occurred in Mountmellick during inter-censal period 2002-2006 has continued through to 2011 though precise figures for 2011 are still pending at time of writing. -

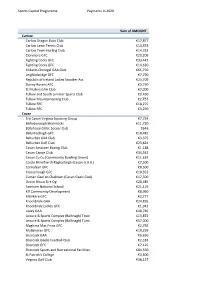

Sports Capital Programme Payments in 2020 Sum of AMOUNT Carlow

Sports Capital Programme Payments in 2020 Sum of AMOUNT Carlow Carlow Dragon Boat Club €17,877 Carlow Lawn Tennis Club €14,353 Carlow Town Hurling Club €14,332 Clonmore GFC €23,209 Fighting Cocks GFC €33,442 Fighting Cocks GFC €14,620 Kildavin Clonegal GAA Club €61,750 Leighlinbridge GFC €7,790 Republic of Ireland Ladies Snooker Ass €23,709 Slaney Rovers AFC €3,750 St Mullins GAA Club €7,000 Tullow and South Leinster Sports Club €9,430 Tullow Mountaineering Club €2,757 Tullow RFC €18,275 Tullow RFC €3,250 Cavan 3rd Cavan Virginia Scouting Group €7,754 Bailieborough Shamrocks €11,720 Ballyhaise Celtic Soccer Club €646 Ballymachugh GFC €10,481 Belturbet GAA Club €3,375 Belturbet Golf Club €23,824 Cavan Amatuer Boxing Club €1,188 Cavan Canoe Club €34,542 Cavan Co Co (Community Bowling Green) €11,624 Coiste Bhreifne Uí Raghaillaigh (Cavan G.A.A.) €7,500 Cornafean GFC €8,500 Crosserlough GFC €10,352 Cuman Gael an Chabhain (Cavan Gaels GAA) €17,500 Droim Dhuin Eire Og €20,485 Farnham National School €21,119 Kill Community Development €8,960 Killinkere GFC €2,777 Knockbride GAA €24,835 Knockbride Ladies GFC €1,942 Lavey GAA €48,785 Leisure & Sports Complex (Ballinagh) Trust €13,872 Leisure & Sports Complex (Ballinagh) Turst €57,000 Maghera Mac Finns GFC €2,792 Mullahoran GFC €10,259 Shercock GAA €6,650 Shercock Gaelic Football Club €2,183 Shercock GFC €7,125 Shercock Sports and Recreational Facilities €84,550 St Patrick's College €3,500 Virginia Golf Club €38,127 Sports Capital Programme Payments in 2020 Virginia Kayak Club €9,633 Cavan Castlerahan -

Ireland P a R T O N E

DRAFT M a r c h 2 0 1 4 REMARKABLE P L A C E S I N IRELAND P A R T O N E Must-see sites you may recognize... paired with lesser-known destinations you will want to visit by COREY TARATUTA host of the Irish Fireside Podcast Thanks for downloading! I hope you enjoy PART ONE of this digital journey around Ireland. Each page begins with one of the Emerald Isle’s most popular destinations which is then followed by several of my favorite, often-missed sites around the country. May it inspire your travels. Links to additional information are scattered throughout this book, look for BOLD text. www.IrishFireside.com Find out more about the © copyright Corey Taratuta 2014 photographers featured in this book on the photo credit page. You are welcome to share and give away this e-book. However, it may not be altered in any way. A very special thanks to all the friends, photographers, and members of the Irish Fireside community who helped make this e-book possible. All the information in this book is based on my personal experience or recommendations from people I trust. Through the years, some destinations in this book may have provided media discounts; however, this was not a factor in selecting content. Every effort has been made to provide accurate information; if you find details in need of updating, please email [email protected]. Places featured in PART ONE MAMORE GAP DUNLUCE GIANTS CAUSEWAY CASTLE INISHOWEN PENINSULA THE HOLESTONE DOWNPATRICK HEAD PARKES CASTLE CÉIDE FIELDS KILNASAGGART INSCRIBED STONE ACHILL ISLAND RATHCROGHAN SEVEN -

En — 24.03.1999 — 003.001 — 1

1985L0350 — EN — 24.03.1999 — 003.001 — 1 This document is meant purely as a documentation tool and the institutions do not assume any liability for its contents ►B COUNCIL DIRECTIVE of 27 June 1985 concerning the Community list of less-favoured farming areas within the meaning of Directive 75/ 268/EEC (Ireland) (85/350/EEC) (OJ L 187, 19.7.1985, p. 1) Amended by: Official Journal No page date ►M1 Council Directive 91/466/EEC of 22 July 1991 L 251 10 7.9.1991 ►M2 Council Directive 96/52/EC of 23 July 1996 L 194 5 6.8.1996 ►M3 Commission Decision 1999/251/EC of 23 March 1999 L 96 29 10.4.1999 Corrected by: ►C1 Corrigendum, OJ L 266, 9.10.1985, p. 18 (85/350/EEC) ►C2 Corrigendum, OJ L 281, 23.10.1985, p. 17 (85/350/EEC) ►C3 Corrigendum, OJ L 74, 19.3.1986, p. 36 (85/350/EEC) 1985L0350 — EN — 24.03.1999 — 003.001 — 2 ▼B COUNCIL DIRECTIVE of 27 June 1985 concerning the Community list of less-favoured farming areas within the meaning of Directive 75/268/EEC (Ireland) (85/350/EEC) THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community, Having regard to Council Directive 75/268/EEC of 28 April 1975 on mountain and hill farming and farming in certain less-favoured areas( 1), aslastamended by Directive 82/786/EEC ( 2), and in particular Article 2 (2) thereof, Having regard to the proposal from the Commission, Having regard to the opinion of the European Parliament (3), WhereasCouncil Directive 75/272/EEC of 28 April 1975 concerning the Community list of less-favoured farming areas within -

2019 Week 35 26.08.19 – 30.08.19

DATE : 02/09/2019 LAOIS COUNTY COUNCIL TIME : 14:14:26 PAGE : 1 P L A N N I N G A P P L I C A T I O N S PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FROM 26/08/19 TO 30/08/19 under section 34 of the Act the applications for permission may be granted permission, subject to or without conditions, or refused; The use of the personal details of planning applicants, including for marketing purposes, maybe unlawful under the Data Protection Acts 1988 - 2003 and may result in action by the Data Protection Commissioner, against the sender, including prosecution FILE APP. DATE DEVELOPMENT DESCRIPTION AND LOCATION EIS PROT. IPC WASTE NUMBER APPLICANTS NAME TYPE RECEIVED RECD. STRU LIC. LIC. 19/485 Andy Close P 26/08/2019 extend existing dwelling, new septic tank system and percolation area and associated site works Moyadd The Swan Co. Laois 19/486 Richard Burke R 26/08/2019 retain a signboard and reduce the height by a half opposite Burnwood lane entrance Burnwood Clonad Portlaoise Co. Laois 19/487 Margaret Somers O'Brien & R 27/08/2019 retain an existing detached domestic shed and Tommy O'Brien associated site works Ballickmoyler Road Graiguecullen Carlow Co. Laois 19/488 Brendan & Triona Kealy P 27/08/2019 construct a domestic garage and all associated site works Shanrath Wolfhill Co. Laois DATE : 02/09/2019 LAOIS COUNTY COUNCIL TIME : 14:14:26 PAGE : 2 P L A N N I N G A P P L I C A T I O N S PLANNING APPLICATIONS RECEIVED FROM 26/08/19 TO 30/08/19 under section 34 of the Act the applications for permission may be granted permission, subject to or without conditions, or refused; The use of the personal details of planning applicants, including for marketing purposes, maybe unlawful under the Data Protection Acts 1988 - 2003 and may result in action by the Data Protection Commissioner, against the sender, including prosecution FILE APP. -

Midlands-Our-Past-Our-Pleasure.Pdf

Guide The MidlandsIreland.ie brand promotes awareness of the Midland Region across four pillars of Living, Learning, Tourism and Enterprise. MidlandsIreland.ie Gateway to Tourism has produced this digital guide to the Midland Region, as part of suite of initiatives in line with the adopted Brand Management Strategy 2011- 2016. The guide has been produced in collaboration with public and private service providers based in the region. MidlandsIreland.ie would like to acknowledge and thank those that helped with research, experiences and images. The guide contains 11 sections which cover, Angling, Festivals, Golf, Walking, Creative Community, Our Past – Our Pleasure, Active Midlands, Towns and Villages, Driving Tours, Eating Out and Accommodation. The guide showcases the wonderful natural assets of the Midlands, celebrates our culture and heritage and invites you to discover our beautiful region. All sections are available for download on the MidlandsIreland.ie Content: Images and text have been provided courtesy of Áras an Mhuilinn, Athlone Art & Heritage Limited, Athlone, Institute of Technology, Ballyfin Demense, Belvedere House, Gardens & Park, Bord na Mona, CORE, Failte Ireland, Lakelands & Inland Waterways, Laois Local Authorities, Laois Sports Partnership, Laois Tourism, Longford Local Authorities, Longford Tourism, Mullingar Arts Centre, Offaly Local Authorities, Westmeath Local Authorities, Inland Fisheries Ireland, Kilbeggan Distillery, Kilbeggan Racecourse, Office of Public Works, Swan Creations, The Gardens at Ballintubbert, The Heritage at Killenard, Waterways Ireland and the Wineport Lodge. Individual contributions include the work of James Fraher, Kevin Byrne, Andy Mason, Kevin Monaghan, John McCauley and Tommy Reynolds. Disclaimer: While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy in the information supplied no responsibility can be accepted for any error, omission or misinterpretation of this information. -

A Provisional Inventory of Ancient and Long-Established Woodland in Ireland

A provisional inventory of ancient and long‐established woodland in Ireland Irish Wildlife Manuals No. 46 A provisional inventory of ancient and long‐ established woodland in Ireland Philip M. Perrin and Orla H. Daly Botanical, Environmental & Conservation Consultants Ltd. 26 Upper Fitzwilliam Street, Dublin 2. Citation: Perrin, P.M. & Daly, O.H. (2010) A provisional inventory of ancient and long‐established woodland in Ireland. Irish Wildlife Manuals, No. 46. National Parks and Wildlife Service, Department of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government, Dublin, Ireland. Cover photograph: St. Gobnet’s Wood, Co. Cork © F. H. O’Neill The NPWS Project Officer for this report was: Dr John Cross; [email protected] Irish Wildlife Manuals Series Editors: N. Kingston & F. Marnell © National Parks and Wildlife Service 2010 ISSN 1393 – 6670 Ancient and long‐established woodland inventory ________________________________________ CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 2 INTRODUCTION 3 Rationale 3 Previous research into ancient Irish woodland 3 The value of ancient woodland 4 Vascular plants as ancient woodland indicators 5 Definitions of ancient and long‐established woodland 5 Aims of the project 6 DESK‐BASED RESEARCH 7 Overview 7 Digitisation of ancient and long‐established woodland 7 Historic maps and documentary sources 11 Interpretation of historical sources 19 Collation of previous Irish ancient woodland studies 20 Supplementary research 22 Summary of desk‐based research 26 FIELD‐BASED RESEARCH 27 Overview 27 Selection of sites -

Road Schedule for County Laois

Survey Summary Date: 21/06/2012 Eng. Area Cat. RC Road Starting At Via Ending At Length Central Eng Area L LP L-1005-0 3 Roads in Killinure called Mountain Farm, Rockash, ELECTORAL BORDER 7276 Burkes Cross The Cut, Ross Central Eng Area L LP L-1005-73 ELECTORAL BORDER ROSS BALLYFARREL 6623 Central Eng Area L LP L-1005-139 BALLYFARREL BELLAIR or CLONASLEE 830.1 CAPPANAPINION Central Eng Area L LP L-1030-0 3 Roads at Killinure School Inchanisky, Whitefields, 3 Roads South East of Lacca 1848 Lacka Bridge in Lacca Townsland Central Eng Area L LP L-1031-0 3 Roads at Roundwood Roundwood, Lacka 3 Roads South East of Lacca 2201 Bridge in Lacca Townsland Central Eng Area L LP L-1031-22 3 Roads South East of Lacca CARDTOWN 3 Roads in Cardtown 1838 Bridge in Lacca Townsland townsland Central Eng Area L LP L-1031-40 3 Roads in Cardtown Johnsborough., Killeen, 3 Roads at Cappanarrow 2405 townsland Ballina, Cappanrrow Bridge Central Eng Area L LP L-1031-64 3 Roads at Cappanarrow Derrycarrow, Longford, DELOUR BRIDGE 2885 Bridge Camross Central Eng Area L LP L-1034-0 3 Roads in Cardtown Cardtown, Knocknagad, 4 Roads in Tinnakill called 3650 townsland Garrafin, Tinnakill Tinnakill X Central Eng Area L LP L-1035-0 3 Roads in Lacca at Church Lacka, Rossladown, 4 Roads in Tinnakill 3490 of Ireland Bushorn, Tinnahill Central Eng Area L LP L-1075-0 3 Roads at Paddock School Paddock, Deerpark, 3 Roads in Sconce Lower 2327 called Paddock X Sconce Lower Central Eng Area L LP L-1075-23 3 Roads in Sconce Lower Sconce Lower, Briscula, LEVISONS X 1981 Cavan Heath Survey Summary Date: 21/06/2012 Eng. -

The-Garden-Heritage-Of-County-Laois.Pdf

GardenThe Heritage of COUNTY LAOIS GardenThe Heritage of COUNTY LAOIS housands of gardeners have passed through Laois. They include Stone Age farmers, medieval monks, cottage holders, great landowners and Laois men 4like Noel Keenan, who transformed a cow paddock into his vision of paradise. This brochure invites you to explore the gardening heritage of Laois. It includes descriptions of five gardens open to the public. The final pages mention just a few of the plants that generations of gardeners have left behind in the county’s private gardens, hedgerows and on its roadsides. Three men had a great influence on the gardens of County Laois. In the late 1800s, William Robinson worked as the garden foreman at Ballykilcavan. After a quarrel with his employer, Robinson put out the fires that heated the glasshouses and opened all the windows. Then he fled in the night. He never again worked in Ireland, but the Irish landscape and its gardens had a deep influence upon him. In England, Robinson scorned “floral rugs” and championed a more natural style of gardening. He is largely responsible for way most gardens look today. From 1908 until the foundation of the State in 1922, avid plant collector Murray Hornibrook made his home at Knapton House near Abbeyleix. He travelled from the wilds of Connemara to the walled gardens of the great houses, looking for interesting garden plants. Although Hornibrook is best known for his collection of dwarf conifers, several modern garden plants are propagated largely because he took note of them. In recent years, the county’s most influential plantsman was the late Noel Keenan. -

ST MANMANS NEWSLETTER Eighth Sunday in Ordinary Time Sunday 3Rd March 2019 Fr

ST MANMANS NEWSLETTER Eighth Sunday in Ordinary Time Sunday 3rd March 2019 Fr. Thomas O’Reilly, P.P. Phone: 057-864-8030 Parish Website: www.clonasleeparish.com Diocesan Website: www.kandle.ie Local Safeguarding Representatives: Jackie Hyland, Caroline Mills Safeguarding Children, Diocesan Liaison Person: Mick Daly: 085-802-1633 Email: [email protected] WEEKEND MASSES Saturday 8 pm Sunday 10 am Bernard Hill, River View & formerly Tullamore WEEKDAY MASSES & Manchester Monday, Friday 9 am Margaret Mitchell, Manchester Wed – Ash Wednesday 10 am & 7:30 pm Paddy Breen, Slieve Bloom Park Thursday – Confirmation 11 am Saturday 9th March – 8 pm CONFESSIONS Annie Flynn, Ross Every 1st Friday before 7:30 pm Mass. Tom Smith, Bellair SACRAMENT OF BAPTISM Peter, Tom & Annie Carroll, Castlecuffe Baptisms available on Saturdays. To arrange a Martha Flynn, Coolnabanch date contact 057-864-8030. Sunday 10th March – 10 am SACRAMENT OF MARRIAGE Lar Breslin, Glenkeen It is advisable to give 6 months’ notice of your Please pray for Paddy O’Neill, London & intention to marry to the Church and the Registrar. formerly of Ross who died during the week. Contact 057-864-8030 to book the church. All ASH WEDNESDAY couples getting married must attend a pre- The distribution of ashes will be Wednesday 6th marriage course. Contact ACCORD for marriage March at 10 am and 7:30 pm mass. preparation courses on 057-934-1831 or 1st COMMUNION PROGRAMME [email protected]. Also on offer marriage & The First Communion programme continues next relationship counselling service Mon-Fri 9:30 am- Sunday March 10th at the 10 am Mass.