The Debate Over Microtransactions Isn't Really About Money at All

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysis of Global Regulatory Schemes on Chance-Based Microtransactions

Analysis of Global Regulatory Schemes on Chance-Based Microtransactions ANTHONY WEN - T S U N W O N G I. MICROTRANSACTIONS – A VIDEO GAME MONETIZATION MODEL icrotransactions are financial transactions for a digital good or service. These transactions are often seen in video game monetization models M where consumers purchase a currency or credit to spend on in-game additions. Companies have found innovative ways of introducing microtransactions to monetize games through business models such as free-to- play “freemium” models or by reducing the initial cost of purchasing a game and shifting the cost onto additional features. Other companies introduced microtransactions as a method of obtaining virtual gameplay goods and services. Some products are chance-based where the obtained outcome is randomized according to a table of probabilities. These are often referred to as “gachapon” and “loot boxes.” This paper seeks to examine and compare this chance-based nature, its effectiveness in video game microtransactions and their financial and psychological influences on the consumer to those of traditional gambling games. Furthermore, an analysis of Canadian and foreign legislation will be done to identify downfalls in Canadian legislation, determine necessary reformations to Canadian gaming law, and identify effective methods that will strengthen the regulatory regime. II. CHANCE-BASED MICROTRANSACTIONS A “Gachapon” is a Japanese vending-machine-style capsule toy dispenser; its name being an onomatopoeia of the sound of the hand-crank (“gacha”) and the sound of the capsule landing in the receptacle (“pon”). A consumer would pay the fee, turn the hand-crank, and a capsule containing a prize from a predefined list would be dispensed. -

Exploring Motivations for Virtual Rewards in Online F2P Gacha Games: Considering

Exploring motivations for virtual rewards in online F2P Gacha games: Considering income level, consumption habits and game settings In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Bachelor of Science in Global Business by DONG Yulai 1025594 May, 2020 ABSTRACT The objective of this study is to figure out players’ motivation on paying for virtual rewards in online F2P Gacha games. Based on the previous studies and primary survey, this paper will draw a conclusion with a primary survey collection which covered more than 3700 adept Gacha game players. Possible factors including income level, consuming habits and game settings which may be players’ paying motivations are analyzed to weigh their dependency about how they sustain and influence players’ playing and consuming behaviors. The correlation analysis and regression analysis will be used to measure the relationship between these factors and payment for Gacha games. As a result, players’ income level has a significant correlation with their payment in Gacha games while their consuming habits in other virtual goods doesn’t have a significant positive correlation with paying for Gacha games. Keywords: F2P Gacha game; virtual goods; consumer behavior; online payment INTRODUCTION Gacha game is generated from Gashapon, a kind of capsule toy derived from Japanese Bandai company that consumers can get a random one from a sets of given toys in a loot box (Toto, 2012). The system of Gashapon and loot box are applied to the initially Free-to-Play on- line game no matter PC games or mobile games since 2010s. However, the loot box system in these so-called “free-to-play” game lures players to spend a lot on in-game virtual currency for the possibility of getting random virtual rewards such as rare items or game characters (Nieborg, 2016). -

Lootboxes" in Digital Games - a Gamble with Consumers in Need of Regulation? an Evaluation Based on Learnings from Japan

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Koeder, Marco Josef; Tanaka, Ema; Mitomo, Hitoshi Conference Paper "Lootboxes" in digital games - A gamble with consumers in need of regulation? An evaluation based on learnings from Japan 22nd Biennial Conference of the International Telecommunications Society (ITS): "Beyond the Boundaries: Challenges for Business, Policy and Society", Seoul, Korea, 24th-27th June, 2018 Provided in Cooperation with: International Telecommunications Society (ITS) Suggested Citation: Koeder, Marco Josef; Tanaka, Ema; Mitomo, Hitoshi (2018) : "Lootboxes" in digital games - A gamble with consumers in need of regulation? An evaluation based on learnings from Japan, 22nd Biennial Conference of the International Telecommunications Society (ITS): "Beyond the Boundaries: Challenges for Business, Policy and Society", Seoul, Korea, 24th-27th June, 2018, International Telecommunications Society (ITS), Calgary This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/190385 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

JAM-BOX Retro PACK 16GB AMSTRAD

JAM-BOX retro PACK 16GB BMX Simulator (UK) (1987).zip BMX Simulator 2 (UK) (19xx).zip Baby Jo Going Home (UK) (1991).zip Bad Dudes Vs Dragon Ninja (UK) (1988).zip Barbarian 1 (UK) (1987).zip Barbarian 2 (UK) (1989).zip Bards Tale (UK) (1988) (Disk 1 of 2).zip Barry McGuigans Boxing (UK) (1985).zip Batman (UK) (1986).zip Batman - The Movie (UK) (1989).zip Beachhead (UK) (1985).zip Bedlam (UK) (1988).zip Beyond the Ice Palace (UK) (1988).zip Blagger (UK) (1985).zip Blasteroids (UK) (1989).zip Bloodwych (UK) (1990).zip Bomb Jack (UK) (1986).zip Bomb Jack 2 (UK) (1987).zip AMSTRAD CPC Bonanza Bros (UK) (1991).zip 180 Darts (UK) (1986).zip Booty (UK) (1986).zip 1942 (UK) (1986).zip Bravestarr (UK) (1987).zip 1943 (UK) (1988).zip Breakthru (UK) (1986).zip 3D Boxing (UK) (1985).zip Bride of Frankenstein (UK) (1987).zip 3D Grand Prix (UK) (1985).zip Bruce Lee (UK) (1984).zip 3D Star Fighter (UK) (1987).zip Bubble Bobble (UK) (1987).zip 3D Stunt Rider (UK) (1985).zip Buffalo Bills Wild West Show (UK) (1989).zip Ace (UK) (1987).zip Buggy Boy (UK) (1987).zip Ace 2 (UK) (1987).zip Cabal (UK) (1989).zip Ace of Aces (UK) (1985).zip Carlos Sainz (S) (1990).zip Advanced OCP Art Studio V2.4 (UK) (1986).zip Cauldron (UK) (1985).zip Advanced Pinball Simulator (UK) (1988).zip Cauldron 2 (S) (1986).zip Advanced Tactical Fighter (UK) (1986).zip Championship Sprint (UK) (1986).zip After the War (S) (1989).zip Chase HQ (UK) (1989).zip Afterburner (UK) (1988).zip Chessmaster 2000 (UK) (1990).zip Airwolf (UK) (1985).zip Chevy Chase (UK) (1991).zip Airwolf 2 (UK) -

BANDAI NAMCO Group FACT BOOK 2019 BANDAI NAMCO Group FACT BOOK 2019

BANDAI NAMCO Group FACT BOOK 2019 BANDAI NAMCO Group FACT BOOK 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 BANDAI NAMCO Group Outline 3 Related Market Data Group Organization Toys and Hobby 01 Overview of Group Organization 20 Toy Market 21 Plastic Model Market Results of Operations Figure Market 02 Consolidated Business Performance Capsule Toy Market Management Indicators Card Product Market 03 Sales by Category 22 Candy Toy Market Children’s Lifestyle (Sundries) Market Products / Service Data Babies’ / Children’s Clothing Market 04 Sales of IPs Toys and Hobby Unit Network Entertainment 06 Network Entertainment Unit 22 Game App Market 07 Real Entertainment Unit Top Publishers in the Global App Market Visual and Music Production Unit 23 Home Video Game Market IP Creation Unit Real Entertainment 23 Amusement Machine Market 2 BANDAI NAMCO Group’s History Amusement Facility Market History 08 BANDAI’s History Visual and Music Production NAMCO’s History 24 Visual Software Market 16 BANDAI NAMCO Group’s History Music Content Market IP Creation 24 Animation Market Notes: 1. Figures in this report have been rounded down. 2. This English-language fact book is based on a translation of the Japanese-language fact book. 1 BANDAI NAMCO Group Outline GROUP ORGANIZATION OVERVIEW OF GROUP ORGANIZATION Units Core Company Toys and Hobby BANDAI CO., LTD. Network Entertainment BANDAI NAMCO Entertainment Inc. BANDAI NAMCO Holdings Inc. Real Entertainment BANDAI NAMCO Amusement Inc. Visual and Music Production BANDAI NAMCO Arts Inc. IP Creation SUNRISE INC. Affiliated Business -

TITLES = (Language: EN Version: 20101018083045

TITLES = http://wiitdb.com (language: EN version: 20101018083045) 010E01 = Wii Backup Disc DCHJAF = We Cheer: Ohasta Produce ! Gentei Collabo Game Disc DHHJ8J = Hirano Aya Premium Movie Disc from Suzumiya Haruhi no Gekidou DHKE18 = Help Wanted: 50 Wacky Jobs (DEMO) DMHE08 = Monster Hunter Tri Demo DMHJ08 = Monster Hunter Tri (Demo) DQAJK2 = Aquarius Baseball DSFE7U = Muramasa: The Demon Blade (Demo) DZDE01 = The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess (E3 2006 Demo) R23E52 = Barbie and the Three Musketeers R23P52 = Barbie and the Three Musketeers R24J01 = ChibiRobo! R25EWR = LEGO Harry Potter: Years 14 R25PWR = LEGO Harry Potter: Years 14 R26E5G = Data East Arcade Classics R27E54 = Dora Saves the Crystal Kingdom R27X54 = Dora Saves The Crystal Kingdom R29E52 = NPPL Championship Paintball 2009 R29P52 = Millennium Series Championship Paintball 2009 R2AE7D = Ice Age 2: The Meltdown R2AP7D = Ice Age 2: The Meltdown R2AX7D = Ice Age 2: The Meltdown R2DEEB = Dokapon Kingdom R2DJEP = Dokapon Kingdom For Wii R2DPAP = Dokapon Kingdom R2DPJW = Dokapon Kingdom R2EJ99 = Fish Eyes Wii R2FE5G = Freddi Fish: Kelp Seed Mystery R2FP70 = Freddi Fish: Kelp Seed Mystery R2GEXJ = Fragile Dreams: Farewell Ruins of the Moon R2GJAF = Fragile: Sayonara Tsuki no Haikyo R2GP99 = Fragile Dreams: Farewell Ruins of the Moon R2HE41 = Petz Horse Club R2IE69 = Madden NFL 10 R2IP69 = Madden NFL 10 R2JJAF = Taiko no Tatsujin Wii R2KE54 = Don King Boxing R2KP54 = Don King Boxing R2LJMS = Hula Wii: Hura de Hajimeru Bi to Kenkou!! R2ME20 = M&M's Adventure R2NE69 = NASCAR Kart Racing -

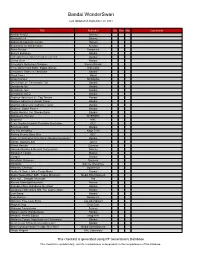

Bandai Wonderswan

Bandai WonderSwan Last Updated on September 29, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments Anchor Field Z Sammy Armored Unit Sammy Bakuso Dekotora Densetsu Human beatmania for Wonderswan Konami Bistro Recipe Banpresto Buffers Evolution Bandai Card Captor Sakura: Sakura to Fushigi na Clow Card Bandai Chaos Gear Bandai Chocobo's Mysterious Dungeon Square/Bandai Chou-Denki Card Battle: Kappa Games Kobunsha Chouaniki: Otoko no Tamafuda Bandai Clock Tower Naxat Crazy Climber Nichibutsu D's Garage 21: Taneomaku Tori Bandai Densha de Go Bandai Densha de Go! Bandai Densha de Go! 2 Bandai Digimon Adventure 02: Tag Tamers Bandai Digimon Adventure: Anode Tamer Bandai Digimon Adventure: Cathode Trainer Bandai Digimon: Digital Partner Bandai Digital Monster Ver. WonderSwan Bandai Dokodemo Hamster INTERBEC Engacho! NAC Fever Sankyo Koushiki Pachinko Simulation BEC Final Lap 2000 Bandai Fire Pro Wrestling Kaga Tech Fishing Freaks: Bass Rise BEC From TV Animation One Piece: Mezase Kaizokuou! Bandai Ganso Jajamaru-kun Jaleco Glocal Hexcite Success Gomoku Narabe & Reversi Touryuumon Sammy Gorakuoh Tango! Mebius Gunpey Bandai Hanafuda Shiyouyo Success Harobots Sunrise Interactive Hataraku Chocobo Squaresoft Hunter X Hunter: Ishi o Tsugu Mono Bandai Keiba Yosou Shien Soft - Yosou Shinkaron Media Entertainment Kiss Yori... Seaside Seranade Kid Klonoa: Moonlight Museum Namco Kosodate Quiz Dokodemo My Angel Bandai Langrisser Millennium WS: The Last Century Bandai Last Stand Bandai Lode Runner Banpresto Macross: True Love Song Lay-Up (Upstar) Magical Drop Data East Mahjong Touryuumon Sammy Makaimura for WonderSwan Bandai Medarot: Perfect Edition Imagineer Meitantei Conan: Majutsushi no Chousenjou Bandai Meitantei Conan: Nishi no Meitantei Saidai no Kiki!? Bandai Meta Communication Therapy: Nee Kiite! Media Entertainment Mingle Magnet HAL Laboratory This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database. -

Fogyasztóvédelem Sajtószemle

Fogyasztóvédő Alapítvány - FVA 23 éve a Fogyasztókért Fogyasztóvédő Alapítvány Heti sajtószemle 2020. 30. hét Feloldotta a Nébih a baromfizárlatot ÁLLATEGÉSZSÉGÜGY Az országos főállatorvos július 15-én visszavonta a madárinfluenza miatt elrendelt, a baromfik zártan tartására vonatkozó előírást, azonban a zártan etetés és itatás a jövőben is kötelező - közölte a Nemzeti Élelmiszerlánc-biztonsági Hivatal (Nébih). A hivatal hangsúlyozta: fontos, hogy az állattartók betartsák a járványvédelmi minimumfeltételeket is. A könnyítésre azután kerülhetett sor, hogy a Nébih laboratóriuma június 5-e óta nem mutatott ki újabb fertőzést sem házi, sem vadon élő, sem pedig fogságban tartott madarakban. Ám a vándormadarak vonulása miatt a vírus továbbra is veszélyt jelent a baromfiállományokra. MW Eredeti (24 Óra, 2020. július 20., hétfő, 7. oldal) Bővítette fogyasztóvédelmi ajánlásait az MNB - az ügyfelet nem érheti hátrány Az elektronikus kommunikációval és szerződéskötéssel, illetve a határon átnyúló szolgáltatókkal kapcsolatos elvárásokkal egészült ki a Magyar Nemzeti Bank fogyasztóvédelmi ajánlása, amelynek címzettjei a pénzügyi szervezetek. A csomag irányt mutat az örökösök és a pénzügyi szervezetek együttműködésére és a szerződéses feltételek megismertetésének ösztönzésére is. A jegybank tisztességes szerződési feltételeket, s az ügyfelekkel folytatott kommunikáció során együttműködést, átláthatóságot, a szolgáltatások összehasonlíthatóságát várja el a piaci szereplőktől, különösképpen a költségek, díjak terén. Jó gyakorlatnak tekinti, hogy a pénzügyi szervezetek áttérnek az elektronikus szolgáltatásra, illetve, hogy ennek során digitálisan elérhetővé teszik a szerződési feltételeket. | VG Eredeti (Világgazdaság, 2020. július 20., hétfő, 4. oldal) 2,2 millió forintra büntették Berki Renátát, mert nem jelölte reklámposztjainál, hogy azok reklámok A Gazdasági Versenyhivatal (GVH) vizsgálata alapján Berki Renáta anélkül reklámozta egy kereskedő cég óráit a közösségi oldalán, hogy megjelölte volna a posztok fizetett jellegét. -

Japanese Media Cultures in Japan and Abroad Transnational Consumption of Manga, Anime, and Media-Mixes

Japanese Media Cultures in Japan and Abroad Transnational Consumption of Manga, Anime, and Media-Mixes Edited by Manuel Hernández-Pérez Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Arts www.mdpi.com/journal/arts Japanese Media Cultures in Japan and Abroad Japanese Media Cultures in Japan and Abroad Transnational Consumption of Manga, Anime, and Media-Mixes Special Issue Editor Manuel Hern´andez-P´erez MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade Special Issue Editor Manuel Hernandez-P´ erez´ University of Hull UK Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Arts (ISSN 2076-0752) from 2018 to 2019 (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/arts/special issues/japanese media consumption). For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Article Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03921-008-4 (Pbk) ISBN 978-3-03921-009-1 (PDF) Cover image courtesy of Manuel Hernandez-P´ erez.´ c 2019 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. -

1480 Legalitas Sistem Monetisasi Lootbox Dalam

Muhammad Theo Rizki Putra & Ariawan Gunadi LEGALITAS SISTEM MONETISASI lootbox DALAM TRANSAKSI GAME ONLINE BERDASARKAN UNDANG-UNDANG NOMOR 11 TAHUN 2008 JO UNDANG-UNDANG NOMOR 19 TAHUN 2016 Volume 3 Nomor 1, Juli 2020 E-ISSN: 2655-7347 LEGALITAS SISTEM MONETISASI LOOTBOX DALAM TRANSAKSI GAME ONLINE BERDASARKAN UNDANG-UNDANG NOMOR 11 TAHUN 2008 JO UNDANG-UNDANG NOMOR 19 TAHUN 2016 Muhammad Theo Rizki Putra (Mahasiswa Program S1 Fakultas Hukum Universitas Tarumanagara) (e-mail: [email protected]) Dr. Ariawan Gunadi, S.H., M.H. (Corresponding Author) (Dosen Fakultas Hukum Universitas Tarumanagara. Meraih Sarjana Hukum pada Fakultas Hukum Universitas Tarumanagara, Magister Hukum pada Fakultas Hukum Universitas Tarumanagara, Doktor (Dr.) pada Fakultas Hukum Universitas Indonesia) (e-mail: [email protected]) Abstract The advancements in technologies of the current world has given birth to many new services for daily consumption and the general betterment of quality of life. These services can be in the form of recreational applications, also known as video games. One of the monetization system used by the video games industry is lootbox monetization system, a system where consumer can buy a lootbox containing of randomized virtual items using real money or other currencies and has raised concerns about the legality of such practices in the eyes of Indonesian laws. How is the legality of this lootbox monetization system according to Act 19 Year 2016 jo Act 11 Year 2008? How responsible is the goverment towards the negative influences and effects of lootbox monetization system? This journal is written using the normative research method. The research data shows that lootbox monetization system has inherent gambling elements and negative influences, but legally still in the grey area of the law. -

YO-KAI WATCH Un Vistazo a Metroid Prime, Uno De El Fenómeno Japonés Llega Con Dos 36 Los Grandes Juegos De La Historia

OPINIÓN EN MODO HARDCORE TodoNOVIEMBRE 2015 JuegosNÚMERO 32 OPINIÓN | REPORTAJES | NOTICIAS | AVANCES Ghost Games apuesta por la velocidad y el estilo en esta nueva entrega de la saga. ¿Cumplirá con las expectativas? NEED FOR SPEED ¿LLEGA A LA META? UNA REALIZACIÓN DE PLAYADICTOS TodoJuegos Editorial Un salto imprescindible s, a estas alturas, mucho más evidente una verdad indes- a estas alturas. Ni tam- Ementible. La sép- poco de la fluidez de la tima generación de experiencia, que es mu- consolas, aquella que cho más radical al pasar tuvo como estrellas a la de una PS3 a una PS4 y Xbox 360 de Microsoft quien haya tenido las y a la PlayStation 3 de Jorge Maltrain Macho dos sabrá de qué hablo. Sony está llegando a su Editor General fin. Y en buena hora. A estos dos factores regular se reste de dar se suman, hoy en día, Cuando se cumplen dos el salto generacional de otros dos de tanto o años del lanzamiento una vez por todas. más peso. El primero es de sus sucesoras, Xbox que las versiones para One y PlayStation 4, no Ya no se trata sólo de “la generación pasada” hay razones objetivas la obvia diferencia en se están convirtiendo para que alguien que se calidad gráfica, notoria en un verdadero chiste. considera un jugador desde el principio, pero Y el ejemplo más claro es el del próximo Call of Equipo de TodoJuegos Duty: Black Ops 3. DIRECTOR Rodrigo Salas Felipe Jorquera Jorge Rodríguez JEFE DE PRODUCCIÓN #LdeA20 #Caleta Cristian Garretón EDITOR GENERAL Y DIAGRAMADOR Andrea Sánchez Luis Puebla #Eidrelle Jorge Maltrain Macho #D_o_G #MaLTRaiN Como leerán en el artí- Electronic Arts, que se ¿Y la segunda razón? culo de esta edición, las la jugó con el próximo Es simple: el catálogo. -

A Study on the Purchase Factors of Mobile Game Loot Box - Taking Tower of Saviors As an Example

A Study on the Purchase Factors of Mobile Game Loot Box - Taking Tower of Saviors as an Example Wei Han Hsu, National Yunlin University of Science and Technology, Taiwan Wen Shan Chang, National Yunlin University of Science and Technology, Taiwan The Asian Conference on the Social Sciences 2019 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract With the rapid development of smart phones, nearly 70% of Taiwan's population currently owns smart phones, and nearly 90% of Google Play users have access to mobile Internet. With the integration of smart phones into people's lives, they also drives the demand for APP applications. The needs of the program. The game-related APP is currently the most profitable category in the software market. It also represents that leisure time of playing mobile games has become a part of many people's daily entertainment. In the current business mode of mobile games, many popular games attract players by means of free play, and loot box to stimulate the player's desire to purchase. The decisive factors affecting the desire to purchase will be game developers and important information for marketers. Therefore, this study will use the well-known mobile game “Tower of Saviors" as an example to explore the purchase factors of the loot box. This study is based on the EKB (Engel-Kollat-Blackwell) Model and conducts in-depth interviews with ten players. The results of the study shown that among the many factors affecting purchase, consumers will choose a lottery because of their quality and ability. The appearance of the character is also the main factor affecting the motivation of purchase.