Myanmar 1988 to 1998 Happy 10Th Anniversary?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aung San Suu Kyi (1945- )

Aung San Suu Kyi (1945 - ) Major Events in the Life of a Revolutionary Leader All terms appearing in bold are included in the glossary. 1945 On June 19 in Rangoon (now called Yangon), the capital city of Burma (now called Myanmar), Aung San Suu Kyi was born the third child and only daughter to Aung San, national hero and leader of the Burma Independence Army (BIA) and the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League (AFPFL), and Daw Khin Kyi, a nurse at Rangoon General Hospital. Aung San Suu Kyi was born into a country with a complex history of colonial domination that began late in the nineteenth century. After a series of wars between Burma and Great Britain, Burma was conquered by the British and annexed to British India in 1885. At first, the Burmese were afforded few rights and given no political autonomy under the British, but by 1923 Burmese nationals were permitted to hold select government offices. In 1935, the British separated Burma from India, giving the country its own constitution, an elected assembly of Burmese nationals, and some measure of self-governance. In 1941, expansionist ambitions led the Japanese to invade Burma, where they defeated the British and overthrew their colonial administration. While at first the Japanese were welcomed as liberators, under their rule more oppressive policies were instituted than under the British, precipitating resistance from Burmese nationalist groups like the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League (AFPFL). In 1945, Allied forces drove the Japanese out of Burma and Britain resumed control over the country. 1947 Aung San negotiated the full independence of Burma from British control. -

↓ Burma (Myanmar)

↓ Burma (Myanmar) Population: 51,000,000 Capital: Rangoon Political Rights: 7 Civil Liberties: 7 Status: Not Free Trend Arrow: Burma received a downward trend arrow due to the largest offensive against the ethnic Karen population in a decade and the displacement of thousands of Karen as a result of the attacks. Overview: Although the National Convention, tasked with drafting a new constitution as an ostensible first step toward democracy, was reconvened by the military regime in October 2006, it was boycotted by the main opposition parties and met amid a renewed crackdown on opposition groups. Aung San Suu Kyi, the leader of the opposition National League for Democracy (NLD) party, remained under house arrest in 2006, and the activities of the NLD were severely curtailed. Meanwhile, a wide range of human rights violations against political activists, journalists, civil society actors, and members of ethnic and religious minority groups continued unabated throughout the year. The military pressed ahead with its offensive against ethnic Karen rebels, displacing thousands of villagers and prompting numerous reports of human rights abuses. The campaign, the largest against the Karen since 1997, had been launched in November 2005. After occupation by the Japanese during World War II, Burma achieved independence from Great Britain in 1948. The military has ruled since 1962, when the army overthrew an elected government that had been buffeted by an economic crisis and a raft of ethnic insurgencies. During the next 26 years, General Ne Win’s military rule helped impoverish what had been one of Southeast Asia’s wealthiest countries. The present junta, led by General Than Shwe, dramatically asserted its power in 1988, when the army opened fire on peaceful, student-led, prodemocracy protesters, killing an estimated 3,000 people. -

Burma's Long Road to Democracy

UNITED STATES InsTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT Priscilla Clapp A career officer in the U.S. Foreign Service, Priscilla Clapp served as U.S. chargé d’affaires and chief of mission in Burma (Myanmar) from June 1999 to August 2002. After retiring from the Foreign Service, she has continued to Burma’s Long Road follow events in Burma closely and wrote a paper for the United States Institute of Peace entitled “Building Democracy in Burma,” published on the Institute’s Web site in July 2007 as Working Paper 2. In this Special to Democracy Report, the author draws heavily on her Working Paper to establish the historical context for the Saffron Revolution, explain the persistence of military rule in Burma, Summary and speculate on the country’s prospects for political transition to democracy. For more detail, particularly on • In August and September 2007, nearly twenty years after the 1988 popular uprising the task of building the institutions for stable democracy in Burma, public anger at the government’s economic policies once again spilled in Burma, see Working Paper 2 at www.usip.org. This into the country’s city streets in the form of mass protests. When tens of thousands project was directed by Eugene Martin, and sponsored by of Buddhist monks joined the protests, the military regime reacted with brute force, the Institute’s Center for Conflict Analysis and Prevention. beating, killing, and jailing thousands of people. Although the Saffron Revolution was put down, the regime still faces serious opposition and unrest. -

Burma Road to Poverty: a Socio-Political Analysis

THE BURMA ROAD TO POVERTY: A SOCIO-POLITICAL ANALYSIS' MYA MAUNG The recent political upheavals and emergence of what I term the "killing field" in the Socialist Republic of Burma under the military dictatorship of Ne Win and his successors received feverish international attention for the brief period of July through September 1988. Most accounts of these events tended to be journalistic and failed to explain their fundamental roots. This article analyzes and explains these phenomena in terms of two basic perspec- tives: a historical analysis of how the states of political and economic devel- opment are closely interrelated, and a socio-political analysis of the impact of the Burmese Way to Socialism 2, adopted and enforced by the military regime, on the structure and functions of Burmese society. Two main hypotheses of this study are: (1) a simple transfer of ownership of resources from the private to the public sector in the name of equity and justice for all by the military autarchy does not and cannot create efficiency or elevate technology to achieve the utopian dream of economic autarky and (2) the Burmese Way to Socialism, as a policy of social change, has not produced significant and fundamental changes in the social structure, culture, and personality of traditional Burmese society to bring about modernization. In fact, the first hypothesis can be confirmed in light of the vicious circle of direct controls-evasions-controls whereby military mismanagement transformed Burma from "the Rice Bowl of Asia," into the present "Rice Hole of Asia." 3 The second hypothesis is more complex and difficult to verify, yet enough evidence suggests that the tradi- tional authoritarian personalities of the military elite and their actions have reinforced traditional barriers to economic growth. -

Burma Coup Watch

This publication is produced in cooperation with Burma Human Rights Network (BHRN), Burmese Rohingya Organisation UK (BROUK), the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), Progressive Voice (PV), US Campaign for Burma (USCB), and Women Peace Network (WPN). BN 2021/2031: 1 Mar 2021 BURMA COUP WATCH: URGENT ACTION REQUIRED TO PREVENT DESTABILIZING VIOLENCE A month after its 1 February 2021 coup, the military junta’s escalation of disproportionate violence and terror tactics, backed by deployment of notorious military units to repress peaceful demonstrations, underlines the urgent need for substantive international action to prevent massive, destabilizing violence. The junta’s refusal to receive UN diplomatic and CONTENTS human rights missions indicates a refusal to consider a peaceful resolution to the crisis and 2 Movement calls for action confrontation sparked by the coup. 2 Coup timeline 3 Illegal even under the 2008 In order to avert worse violence and create the Constitution space for dialogue and negotiations, the 4 Information warfare movement in Burma and their allies urge that: 5 Min Aung Hlaing’s promises o International Financial Institutions (IFIs) 6 Nationwide opposition immediately freeze existing loans, recall prior 6 CDM loans and reassess the post-coup situation; 7 CRPH o Foreign states and bodies enact targeted 7 Junta’s violent crackdown sanctions on the military (Tatmadaw), 8 Brutal LIDs deployed Tatmadaw-affiliated companies and partners, 9 Ongoing armed conflict including a global arms embargo; and 10 New laws, amendments threaten human rights o The UN Security Council immediately send a 11 International condemnation delegation to prevent further violence and 12 Economy destabilized ensure the situation is peacefully resolved. -

Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar

Myanmar Development Research (MDR) (Present) Enlightened Myanmar Research (EMR) Wing (3), Room (A-305) Thitsar Garden Housing. 3 Street , 8 Quarter. South Okkalarpa Township. Yangon, Myanmar +951 562439 Acknowledgement of Myanmar Development Research This edition of the “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)” is the first published collection of facts and information of political parties which legally registered at the Union Election Commission since the pre-election period of Myanmar’s milestone 2010 election and the post-election period of the 2012 by-elections. This publication is also an important milestone for Myanmar Development Research (MDR) as it is the organization’s first project that was conducted directly in response to the needs of civil society and different stakeholders who have been putting efforts in the process of the political transition of Myanmar towards a peaceful and developed democratic society. We would like to thank our supporters who made this project possible and those who worked hard from the beginning to the end of publication and launching ceremony. In particular: (1) Heinrich B�ll Stiftung (Southeast Asia) for their support of the project and for providing funding to publish “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)”. (2) Party leaders, the elected MPs, record keepers of the 56 parties in this book who lent their valuable time to contribute to the project, given the limited time frame and other challenges such as technical and communication problems. (3) The Chairperson of the Union Election Commission and all the members of the Commission for their advice and contributions. -

The Languages of Pyidawtha and the Burmese Approach to National Development1

The languages of Pyidawtha and the Burmese approach to national development1 Tharaphi Than Abstract: Burma’s first well known welfare plan was entitled Pyidawtha or Happy Land, and it was launched in 1952. In vernacular terms, the literal mean- ing of Pyidawtha is ‘Prosperous Royal Country’. The government’s attempt to sustain tradition and culture and to instil modern aspirations in its citizens was reflected in its choice of the word Pyidawtha. The Plan failed and its impli- cations still overshadow the development framework of Burma. This paper discusses how the country’s major decisions, including whether or not to join the Commonwealth, have been influenced by language; how the term and con- cept of ‘development’ were conceived; how the Burmese translation was coined to attract public support; and how the detailed planning was presented to the masses by the government. The paper also discusses the concerns and anxie- ties of the democratic government led by U Nu in introducing Burma’s first major development plan to a war-torn and bitterly divided country, and why it eventually failed. Keywords: welfare plan; poverty alleviation; insurgency; communism; Pyidawtha; Burmese language Author details: Tharaphi Than is an Assistant Professor in the Department of For- eign Languages and Literatures at Northern Illinois University, DeKalb, IL 60115, USA. E-mail: [email protected]. In May 2011, the new government of Burma convened a workshop entitled ‘Rural Development and Poverty Alleviation’.2 Convened almost 50 years after Burma’s first Development Conference, called Pyidawtha, the 2011 workshop shared some of the ideologies of the Pyidawtha Plan under the government led by Nu. -

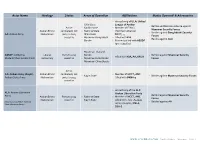

ACLED – Myanmar Conflict Update – Table 1

Actor Name Ideology Status Areas of Operation Affiliations Modus Operandi & Adversaries - Armed wing of ULA: United - Chin State League of Arakan - Battles and Remote violence against Active - Kachin State - Member of FPNCC Myanmar Security Forces Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Rakhine State (Northern Alliance) - Battles against Bangladeshi Security AA: Arakan Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Shan State - NCCT, , , Forces ceasefire - Myanmar-Bangladesh - Allied with KIA - Battles against ALA Border - Formerly allied with ABSDF (pre-ceasefire) - Myanmar-Thailand ABSDF: All Burma Liberal Party to 2015 Border - Battled against Myanmar Security - Allied with KIA, AA, KNLA Students’ Democratic Front democracy ceasefire - Myanmar-India Border Forces - Myanmar-China Border Active AA: Arakan Army (Kayin): Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Member of NCCT, ANC - Kayin State - Battles against Myanmar Security Forces Arakan State Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Allied with DKBA-5 ceasefire - Armed wing of the ALP: ALA: Arakan Liberation Arakan Liberation Party - Battled against Myanmar Security Army Arakan Ethnic Party to 2015 - Rakhine State - Member of NCCT, ANC Forces Nationalism ceasefire - Kayin State - Allied with AA: Arakan (Also known as RSLP: Rakhine - Battled against AA State Liberation Party) Army (Kayin), KNLA, SSA-S WWW.ACLEDDATA.COM | Conflict Update – Myanmar – Table 1 Rohingya Ethnic Active ARSA: Arakan Rohingya - Rakhine State Nationalism; combatant; not Salvation Army - Myanmar-Bangladesh UNKNOWN - Battles against Myanmar Security -

The Generals Loosen Their Grip

The Generals Loosen Their Grip Mary Callahan Journal of Democracy, Volume 23, Number 4, October 2012, pp. 120-131 (Article) Published by The Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: 10.1353/jod.2012.0072 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/jod/summary/v023/23.4.callahan.html Access provided by Stanford University (9 Jul 2013 18:03 GMT) The Opening in Burma the generals loosen their grip Mary Callahan Mary Callahan is associate professor in the Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies at the University of Washington. She is the author of Making Enemies: War and State Building in Burma (2003) and Political Authority in Burma’s Ethnic Minority States: Devolution, Occupation and Coexistence (2007). Burma1 is in the midst of a political transition whose contours suggest that the country’s political future is “up for grabs” to a greater degree than has been so for at least the last half-century. Direct rule by the mili- tary as an institution is over, at least for now. Although there has been no major shift in the characteristics of those who hold top government posts (they remain male, ethnically Burman, retired or active-duty mili- tary officers), there exists a new political fluidity that has changed how they rule. Quite unexpectedly, the last eighteen months have seen the retrenchment of the military’s prerogatives under decades-old draconian “national-security” mandates as well as the emergence of a realm of open political life that is no longer considered ipso facto nation-threat- ening. Leaders of the Tatmadaw (Defense Services) have defined and con- trolled the process. -

Myanmar Security Outlook: a Taxing Year for the Tatmadaw CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 4 Myanmar Security Outlook: A Taxing Year for the Tatmadaw Tin Maung Maung Than Introduction 2015 was a landmark year in Myanmar politics. The general election was held on 8 November and the National League for Democracy (NLD) led by Nobel laureate Aung San Suu Kyi (daughter of Myanmar armed forces founder and independence hero General Aung San) won a landslide victory over the incumbent Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP; a military-backed party led by ex-military officers and President Thein Sein). This was an unexpected development that could challenge the constitutionally-guaranteed political role of the military. The Tatmadaw (literally “royal force”) or Myanmar Defence Services (MDS) also faced a serious challenge to its primary security role when the defunct Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), a renegade ethnic armed organization (EAO), unleashed a furious assault to take over the Kokang Self-Administered Zone (KSAZ; bordering China) leading to a drawn out war of attrition lasting several months and threatening Myanmar-China relations. Tatmadaw: fighting multiple adversaries Despite actively participating in the peace process, launched by President Thein Sein’s elected government since 2011, The MDS found itself engaged in fierce fighting with powerful EAOs in the northern, eastern and south-eastern border regions of Myanmar. In fact, except for the MNDAA, most of these armed groups that engaged in armed conflict with the MDS throughout 2015 were associated with EAOs which had been officially negotiating with the government’s peace-making team toward a nationwide ceasefire agreement (NCA) since March 2014. Moreover, almost all of them had some form of bilateral ceasefire arrangements with the government in the past. -

MYANMAR: Peaceful Protester Jailed for Life

MYANMAR: Peaceful Protester Jailed For Life Pro-democracy activist U Ohn Than is serving a life sentence for peacefully exercising his right to freedom of expression. He was jailed after a trial that was grossly unfair. Veteran protester U Ohn Than was arrested on 23 August 2007 for staging a solo protest outside the US embassy in Myanmar’s largest city, Yangon. He was protesting peacefully against the military government, dressed in a prisoner’s uniform to symbolize his belief that all people in Myanmar are prisoners in their own country. Throughout the protest he held up a placard calling for national and international action to solve the political problems in Myanmar, including a request for UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon to intervene, and a call to the country’s armed forces to disobey their superiors and help overthrow the military government. He was arrested by men in civilian clothes, and taken to Botahtaung Township police station in Yangon. He was held in a military interrogation camp until January 2008, when he was then charged with sedition. U Ohn Than was tried behind closed doors, without any legal representation, inside Yangon’s Insein prison. He was sentenced to life imprisonment on 2 April 2008. He was moved to other prisons three times, the third being Khamti prison, Sagaing Division, in the north of the country, where he is still held. Khamti prison is in a malarial area and prisoners are vulnerable to infection. In June 2008 Amnesty International learned that U Ohn Than was at an advanced stage of cerebral malaria which if left untreated is almost always fatal. -

Myanmar (Burma): a Reading Guide Andrew Selth

Griffith Asia Institute Research Paper Myanmar (Burma): A reading guide Andrew Selth i About the Griffith Asia Institute The Griffith Asia Institute (GAI) is an internationally recognised research centre in the Griffith Business School. We reflect Griffith University’s longstanding commitment and future aspirations for the study of and engagement with nations of Asia and the Pacific. At GAI, our vision is to be the informed voice leading Australia’s strategic engagement in the Asia Pacific— cultivating the knowledge, capabilities and connections that will inform and enrich Australia’s Asia-Pacific future. We do this by: i) conducting and supporting excellent and relevant research on the politics, security, economies and development of the Asia-Pacific region; ii) facilitating high level dialogues and partnerships for policy impact in the region; iii) leading and informing public debate on Australia’s place in the Asia Pacific; and iv) shaping the next generation of Asia-Pacific leaders through positive learning experiences in the region. The Griffith Asia Institute’s ‘Research Papers’ publish the institute’s policy-relevant research on Australia and its regional environment. The texts of published papers and the titles of upcoming publications can be found on the Institute’s website: www.griffith.edu.au/asia-institute ‘Myanmar (Burma): A reading guide’ February 2021 ii About the Author Andrew Selth Andrew Selth is an Adjunct Professor at the Griffith Asia Institute, Griffith University. He has been studying international security issues and Asian affairs for 45 years, as a diplomat, strategic intelligence analyst and research scholar. Between 1974 and 1986 he was assigned to the Australian missions in Rangoon, Seoul and Wellington, and later held senior positions in both the Defence Intelligence Organisation and Office of National Assessments.