Bird Conservation Newsletter No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Namibia & the Okavango

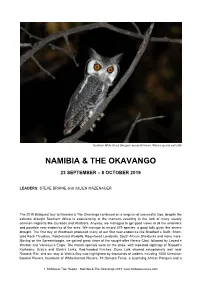

Southern White-faced Owl gave wonderful views. What a special owl! (JM) NAMIBIA & THE OKAVANGO 23 SEPTEMBER – 8 OCTOBER 2019 LEADERS: STEVE BRAINE and JULIEN MAZENAUER The 2019 Birdquest tour to Namibia & The Okavango continued on a long run of successful trips, despite the extreme drought Southern Africa is experiencing at the moment, resulting in the lack of many usually common migrants like Cuckoos and Warblers. Anyway, we managed to get good views at all the endemics and possible near-endemics of the area. We manage to record 379 species, a good tally given the severe drought. The first day at Windhoek produced many of our first near-endemics like Bradfield’s Swift, Short- toed Rock Thrushes, Violet-eared Waxbills, Rosy-faced Lovebirds, South African Shelducks and many more. Moving on the Spreetshoogte, we gained great views of the sought-after Herero Chat, followed by Layard’s Warbler and Verreaux’s Eagle. The Namib specials were on the show, with repeated sightings of Rüppell’s Korhaans, Gray’s and Stark’s Larks, Red-headed Finches. Dune Lark showed exceptionally well near Rostock Ritz, and our stay at Walvis Bay was highlighted by thousands of waders including 1500 Chestnut- banded Plovers, hundreds of White-fronted Plovers, 15 Damara Terns, a surprising African Penguin and a 1 BirdQuest Tour Report : Namibia & The Okavango 2019 www.birdquest-tours.com Northern Giant Petrel as write-in. Huab Lodge delighted us with its Rockrunners, Hartlaub’s Spurfowl, White- tailed Shrike, and amazing sighting of Southern White-faced Owl, African Scops Owl, Freckled Nightjar few feet away and our first White-tailed Shrikes and Violet Wood Hoopoes. -

Trip to Botswana

Trip to Botswana 9-16 November 2014 ScotNature 24 Station Square Office 345 Inverness IV1 1LD Scotland Tel: 07718255265 E-mail: [email protected] www.ScotNature.co.uk ©ScotNature Day 1 09/11/14 Sunday We arrived at Maun airport (from Johannesburg) on time and, after collecting our luggage and meeting Johnny, our guide, we loaded an open safari vehicle. Another quick stop was made at a supermarket to get some lunch snacks, and soon we set off on our four-hour journey to the camp. At first, our journey was rather fruitless and Mopani forests on both sides of the road produced very little. However, as we got closer to the Okavango, more wildlife became visible (and active later in day), so the mammal list was enriched quickly with our first African Elephant, Burchell’s Zebra, Common Warthog, Giraffe, Impala, Tree Squirrel and Yellow Mongoose. Johnny was very keen to press on, so we only shouted the names of the birds that were spotted by the side of the road: Blue Waxbill, Red-billed Francolin, Lilac-breasted Roller, African Grey, Southern Yellow-billed and Red-billed Hornbills, Yellow- billed and Marabou Storks, Fork-tailed Drongo, Arrow-marked and Southern Pied Babblers, Magpie and Southern White-crowned Shrikes, Burchell’s Starling, Red-billed Buffalo-Weaver and White-browed Sparrow-Weaver, to name just a few. Numerous raptors were seen, including White-backed and Hooded Vultures, Brown and Black-chested Snake-Eagles, Tawny Eagle and a gorgeous Bateleur posed for us on the top of a tree close to the road. -

Namibia Crane News 35

Namibia Crane News 35 March 2008 G O O D R AINS – AND FLO O D S – IN TH E NO R TH O F NAM IB IA News of the highest rainfalls in Caprivi and Kavango in 50 years; extensive floods in North Central; and good rains at Etosha and Bushmanland. Although the rains bring about exciting movements of birds, we also have sympathy with those whose lives and homes have been adversely affected by the floods. In this issue 1. Wattled Crane results from aerial survey in north- east Namibia … p1 2. Wattled Crane event book records from East Caprivi … p2 A pair of Wattled Cranes at Lake Ziwey, Ethiopia 3. Wattled Crane records from Bushmanland … p2 (Photo: Gunther Nowald, courtesy of ICF/EWT Partnership) 4. Floods in North Central … p3 5. Blue Crane news from Etosha … p3 Results & Discussion 6. Endangered bird survey in Kavango … p3 Eleven Wattled Cranes were recorded in the Mahango / 7. Why conserve wetlands? … p4 Buffalo area on the lower Kavango floodplains. In 2004 four cranes were seen in this area (Table 1). Twenty CAPR IVI & K AVANG O Wattled Cranes were recorded in the East Caprivi in 2007 (Figure 3; available on request), the same number as in 2004. Most (15) were seen in the Mamili National Park (eight in 2004), and five on the western side of the Kwandu in the Bwabwata National Park. No cranes were seen on the Linyanti-Chobe east of Mamili (eight S tatus of W attled Cranes on the flood- cranes seen in this stretch in 2004), and none on the plains of north-east Namibia: results from Zambezi and eastern floodplains. -

Ultimate Zambia (Including Pitta) Tour

BIRDING AFRICA THE AFRICA SPECIALISTS Ultimate Zambia including Zambia Pitta 2019 Tour Report © Yann Muzika © Yann African Pitta Text by tour leader Michael Mills Photos by tour participants Yann Muzika, John Clark and Roger Holmberg SUMMARY Our first Ultimate Zambia Tour was a resounding success. It was divided into three more manageable sections, namely the North-East Extension, © John Clark © John Main Zambia Tour and Zambia Pitta Tour, each with its own delights. Birding Africa Tour Report Tour Africa Birding On the North-East Pre-Tour we started off driving We commenced the Main Zambia Tour at the Report Tour Africa Birding north from Lusaka to the Bangweulu area, where spectacular Mutinondo Wilderness. It was apparent we found good numbers of Katanga Masked that the woodland and mushitu/gallery forest birds Weaver coming into breeding plumage. Further were finishing breeding, making it hard work to Rosy-throated Longclaw north at Lake Mweru we enjoyed excellent views of track down all the key targets, but we enjoyed good Zambian Yellow Warbler (split from Papyrus Yellow views of Bar-winged Weaver and Laura's Woodland Warbler) and more Katanga Masked Weavers not Warbler and found a pair of Bohm's Flycatchers finally connected with a pair of Whyte's Francolin, Miombo Tit, Bennett's Woodpecker, Amur Falcon, yet in breeding plumage. From here we headed east feeding young. Other highlights included African which we managed to flush. From Mutinondo Cuckoo Finch, African Scops Owl, White-crested to the Mbala area we then visited the Saisi River Barred Owlet, Miombo Rock Thrush and Spotted we headed west with our ultimate destination as Helmetshrike and African Spotted Creeper. -

Lake Ngami Important Bird Area Monitoring Report 2007

LLAAKKE NGAMMI IMPPOORRTAANT BIRDD ARREEAA MMONIITTORRIINNG RREPPOORRT 200077 LAKE NGAMI IMPORTANT BIRD AREA MONITORING REPORT 2007 by P Hancock, M Muller and K Oake INTRODUCTION As part of Birdlife Botswana’s commitment to maintaining a network of sites that are critical for birds both nationally and internationally, the Lake Ngami Important Bird Area (IBA) is monitored annually following BirdLife’s global monitoring framework. This framework is based on the State – Pressure – Response model that has been adopted by the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), and this report is divided into three parts paralleling these components. Part 1 deals with the state of the Lake Ngami IBA, with particular emphasis on the ‘trigger’ species of birds that ‘qualify’ the area as an IBA. Part 2 focuses on pressures or threats to the IBA - these were originally identified by Tyler and Bishop (1998), but some of these have been superceded and a current set of issues has been identified through fieldwork. These threats need to be ranked so that they can be incorporated into the global monitoring framework. Part 3 of the report describes the conservation action undertaken in response to the identified threats. These actions are a measure of progress made towards addressing or mitigating the threats. The actions also need to be objectively ranked for incorporation in the framework. Appendices contain additional information on the birds of Lake Ngami. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special thanks to P Wolski – Harry Oppenheimer Okavango Research Centre – for providing information on the hydrology of Lake Ngami, including the satellite images showing the extent of flooding. Also to M Ntsosa from the Dept. -

Download from And

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) 2009-2014 version Available for download from http://www.ramsar.org/doc/ris/key_ris_e.doc and http://www.ramsar.org/pdf/ris/key_ris_e.pdf Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 (1990), as amended by Resolution VIII.13 of the 8th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2002) and Resolutions IX.1 Annex B, IX.6, IX.21 and IX. 22 of the 9th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2005). Notes for compilers: 1. The RIS should be completed in accordance with the attached Explanatory Notes and Guidelines for completing the Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands. Compilers are strongly advised to read this guidance before filling in the RIS. 2. Further information and guidance in support of Ramsar site designations are provided in the Strategic Framework and guidelines for the future development of the List of Wetlands of International Importance (Ramsar Wise Use Handbook 17, 4th edition). 3. Once completed, the RIS (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Ramsar Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the RIS and, where possible, digital copies of all maps. 1. Name and address of the compiler of this form: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. Holger Kolberg DD MM YY Ramsar STRP focal point for Namibia Directorate Scientific Services 1 1 1 2 1 9 3 Ministry of Environment and Tourism 3 2 3 Windhoek, Namibia Email: [email protected] Designation date Site Reference Number 2. Date this sheet was completed/updated: 11 October 2013 3. Country: NAMIBIA 4. Name of the Ramsar site: Bwabwata – Okavango Ramsar Site 5. -

Namibia & Botswana

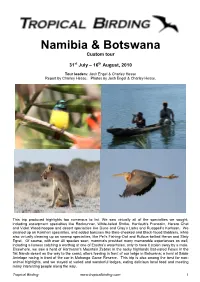

Namibia & Botswana Custom tour 31st July – 16th August, 2010 Tour leaders: Josh Engel & Charley Hesse Report by Charley Hesse. Photos by Josh Engel & Charley Hesse. This trip produced highlights too numerous to list. We saw virtually all of the specialties we sought, including escarpment specialties like Rockrunner, White-tailed Shrike, Hartlaub‟s Francolin, Herero Chat and Violet Wood-hoopoe and desert specialties like Dune and Gray‟s Larks and Rueppell‟s Korhaan. We cleaned up on Kalahari specialties, and added bonuses like Bare-cheeked and Black-faced Babblers, while also virtually cleaning up on swamp specialties, like Pel‟s Fishing-Owl and Rufous-bellied Heron and Slaty Egret. Of course, with over 40 species seen, mammals provided many memorable experiences as well, including a lioness catching a warthog at one of Etosha‟s waterholes, only to have it stolen away by a male. Elsewhere, we saw a herd of Hartmann‟s Mountain Zebras in the rocky highlands Bat-eared Foxes in the flat Namib desert on the way to the coast; otters feeding in front of our lodge in Botswana; a herd of Sable Antelope racing in front of the car in Mahango Game Reserve. This trip is also among the best for non- animal highlights, and we stayed at varied and wonderful lodges, eating delicious local food and meeting many interesting people along the way. Tropical Birding www.tropicalbirding.com 1 The rarely seen arboreal Acacia Rat (Thallomys) gnaws on the bark of Acacia trees (Charley Hesse). 31st July After meeting our group at the airport, we drove into Nambia‟s capital, Windhoek, seeing several interesting birds and mammals along the way. -

The Miombo Ecoregion

The Dynamic of the Conservation Estate (DyCe) Summary Report: The Miombo Ecoregion Prepared by UNEP-WCMC and the University of Edinburgh for the Luc Hoffmann Institute Authors: Vansteelant, N., Lewis, E., Eassom, A., Shannon-Farpón, Y., Ryan C.M, Pritchard R., McNicol I., Lehmann C., Fisher J. and Burgess, N. Contents Summary ....................................................................................................................................2 The Luc Hoffmann Institute and the Dynamics of the Conservation Estate project .................3 The Miombo ecoregion ..............................................................................................................3 The Social-Ecological System ...................................................................................................6 The Social System......................................................................................................................7 The Ecological System ..............................................................................................................9 Forest Cover .............................................................................................................................12 Vegetation types.......................................................................................................................13 Biodiversity values...................................................................................................................15 Challenges for conservation .....................................................................................................16 -

Okavango River Basin Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis: Environmental Flow Module Specialist Report Country: Namibia Discipline: Birds (Avifauna)

EFA Namibia Birds (Avifauna) Okavango River Basin Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis: Environmental Flow Module Specialist Report Country: Namibia Discipline: Birds (Avifauna) Mark Paxton May 2009 1 EFA Namibia Birds (Avifauna). Okavango River Basin Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis: Environmental Flow Module Specialist Report Country: Namibia Discipline: Birds (Avifauna) Author: Mark Paxton Date: May 2009 2 EFA Namibia Birds (Avifauna). EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A series of field trips to the two sites (Kapako and Popa Falls) was undertaken during the period from October 2008 until March 2009, involving myself and various other specialists. These excursions were primarily orientation and information gathering visits but also involved a fair degree of information sharing between the available disciplines. This information sharing helped to clear up many aspects within each discipline and how each section relates to the other. The group discussions and interactions gave me some valuable insight although living in the area and on the river system itself for sixteen years allowed for more of an understanding along with subsequent visits to each sight for further familiarisation regarding the changing river levels and how it affected the birds at each individual site thereby broadening the knowledge base for the birding indicators. From 30th March to 4th April 2009 during the “knowledge capturing” workshop, that was held in Windhoek with the participation of specialists in all other disciples from all of the three countries. Here we collaboratively generated response curves for each of the indicator species and tied this into hydrological and rainfall information over the past forty five years since 1964. Available relevant literature on this aspect i.e. -

Zambia – Pittas, Barbets, Bats, and Rare Antelope

Zambia – pittas, barbets, bats, and rare antelope. November 18 – December 4, 2019. 373 bird species seen + 15-20 heard-only. 41 mammal species seen. Highest diversity days: 155 bird + 15 mammal species at Lochinvar + Nkanga on 11/ 21 and 131 bird + 12 mammal sp. Nkanga 11/22. Organizer: Nate Dias https://www.flickr.com/photos/offshorebirder2/ https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCyYL-LT3VD8wBHAF6NHIibQ/videos?view_as=subscriber/ Agent: Roy Glasspool at Bedrock Africa http://bedrockafrica.com/ Guide: Kyle Branch https://tuskandmane.com/ Special thanks to Rory MacDougall for hosting and stellar guiding in the Choma area and Lochinvar NP. Bird highlights: African Pitta, Slaty Egret, Chaplin's Barbet, Bar-winged Weaver, Bocage's Akalat, Black-necked Eremomela, African Broadbill (displaying male), Woolly-necked Stork, Dwarf Bittern, Rufous-bellied Heron (2 fighting), Crowned Eagle, Lesser Jacana, African Pygmy Goose, Racket-tailed Roller, Half-collared Kingfisher, Böhm's Bee-eater, Rufous-bellied Tit, Eastern Nicator, Purple-throated Cuckoo shrike, Anchieta’s Sunbird, Locust Finch, Carmine Bee-eater colony, 5 Roller species: Purple, Racket-tailed, Lilac-breasted, European & Broad-billed. Mammal highlights: Lord Derby's Anomalure (two interacting and posing), Sitatunga, Serval cat, African Bush Elephant (multiple nursing calves), Kafue Lechwe, Black Lechwe, Sable Antelope, millions of Straw-coloured Fruit Bats, 3 baboon species, Rump-spotted Blue Monkey, Sharpe's Grysbok. Flap-necked Chameleon – Mutinondo Wilderness The origin for this Zambia birding and mammal safari was a discussion with my friend Rob Barnes from the U.K. about Barbets. Rob has seen a large percentage of the African barbets and we got to talking about rare ones and ones he had yet to see. -

Namibia, Okavango and Victoria Falls 18-Day Birding Adventure

NAMIBIA, OKAVANGO AND VICTORIA FALLS 18-DAY BIRDING ADVENTURE 2 – 19 NOVEMBER 2019 Pel’s Fishing Owl is one of our targets on this trip. www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | ITINERARY Namibia, Okavango and Victoria Falls 2019 This is a truly marvelous 2.5-week birding adventure, during which we sample three different countries and spectacular, diverse scenery. We start in the coastal Namib Desert with its impressive dune fields (inhabited by desirable, localized endemics) and lagoons filled with flamingos, pelicans, shorebirds, and some really localized species such as Damara Tern and Chestnut-banded Plover. The mountains of the beautiful Namib Escarpment are next on our itinerary, and here we search for Rosy-faced Lovebird, Herero Chat, Rockrunner, Monteiro’s Hornbill, Damara Red-billed Hornbill, the incomparable batis-like (although largely terrestrial) White-tailed Shrike, and other charismatic endemics of northern Namibia/southern Angola. Heading to the palm-lined Kunene River separating Angola from Namibia (this remote, ruggedly beautiful corner of Namibia is often ignored on birding tours), we look for Angola Cave Chat, Cinderella Waxbill, Rufous-tailed Palm Thrush, Grey Kestrel, and other desirables. Eventually, we leave the endemic-rich desert and enter the grassland, savanna, and woodland of one of Africa’s greatest game parks, Etosha National Park. This must surely be one of the world’s best places for seeing black rhino and big cats, along with all the other African megafauna. And it is excellent for a good range of very special birds, such as Namibia’s dazzling national bird, Crimson-breasted Shrike, the world’s heaviest flying bird, Kori Bustard, the diminutive Pygmy Falcon, and stacks more. -

Managment Plan Bwabwata National Park.Pdf

Management Plan Bwabwata National Park 2013 / 2014 to 2017 / 2018 Ministry of Environment and Tourism Directorate of Regional Services and Parks Management Republic of Namibia Ministry of Environment and Tourism ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This report was commissioned and published by the Ministry of Environment and Tourism (MET) with funding from the Government of the Federal Republic of Germany through KfW. The views expressed in this publication are those of the publishers. Ministry of Environment and Tourism Troskie House, Uhland Street P/Bag 13346, Windhoek Tel: (+264 61) 284 2111 Directorate of Regional Services and Park Management PZN Building, Northern Industrial Area P/Bag 13306, Windhoek Tel: (+264 61) 284 2518 KfW Development Bank Windhoek Office, Namibia 7 Schwerinsburg St P.O. Box 21223 Windhoek +264 61 22 68 53 Citation Ministry of Environment and Tourism, 2013. Managment Plan Bwabwata National Park 2013 /214 to 2017/2014 © MET 2013 Reproduction of this publication for educational and other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited. No photograph may be used in any format without the express permission of the photographer. Cover photo © implemented by Foreword National parks are a vital tool for conserving Namibia’s essential biodiversity. By managing parks, their irreplaceable assets and unlimited potential will be conserved for future generations. In addition, every year Namibia’s National Parks draw large numbers of tourists to Namibia, generating employment and stimulating development nationwide. National Parks also provide a unique opportunity to benefit local communities through rural development while providing research, education and recreation opportunities.