Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lurking in the Shadows: Wide-Separation Gas Giants As Tracers of Planet Formation

Lurking in the Shadows: Wide-Separation Gas Giants as Tracers of Planet Formation Thesis by Marta Levesque Bryan In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Pasadena, California 2018 Defended May 1, 2018 ii © 2018 Marta Levesque Bryan ORCID: [0000-0002-6076-5967] All rights reserved iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost I would like to thank Heather Knutson, who I had the great privilege of working with as my thesis advisor. Her encouragement, guidance, and perspective helped me navigate many a challenging problem, and my conversations with her were a consistent source of positivity and learning throughout my time at Caltech. I leave graduate school a better scientist and person for having her as a role model. Heather fostered a wonderfully positive and supportive environment for her students, giving us the space to explore and grow - I could not have asked for a better advisor or research experience. I would also like to thank Konstantin Batygin for enthusiastic and illuminating discussions that always left me more excited to explore the result at hand. Thank you as well to Dimitri Mawet for providing both expertise and contagious optimism for some of my latest direct imaging endeavors. Thank you to the rest of my thesis committee, namely Geoff Blake, Evan Kirby, and Chuck Steidel for their support, helpful conversations, and insightful questions. I am grateful to have had the opportunity to collaborate with Brendan Bowler. His talk at Caltech my second year of graduate school introduced me to an unexpected population of massive wide-separation planetary-mass companions, and lead to a long-running collaboration from which several of my thesis projects were born. -

Astrotalk: Behind the News Headlines

AstroTalk: Behind the news headlines Richard de Grijs (何锐思) (Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia) The Gaia ‘Sausage’ galaxy Our Milky Way galaxy has most likely collided or otherwise interacted with numerous other galaxies during its lifetime. Indeed, such interactions are common cosmic occurrences. Astronomers can deduce the history of mass accretion onto the Milky Way from a study of debris in the halo of the galaxy left as the tidal residue of such episodes. That approach has worked particularly well for studies of the most recent merger events, like the infall of the Sagittarius dwarf galaxy into the Milky Way’s centre a few billion years ago, which left tidal streamers of stars visiBle in galaxy maps. The damaging effects these encounters can cause to the Milky Way have, however, not been as well studied, and events even further in the past are even less obvious as they Become Blurred By the galaxy’s natural motions and evolution. Some episodes in the Milky Way’s history, however, were so cataclysmic that they are difficult to hide. Scientists have known for some time that the Milky Way’s halo of stars drastically changes in character with distance from the galactic centre, as revealed by the chemical composition—the ‘metallicity’—of the stars, the stellar motions, and the stellar density. Harvard astronomer Federico Marinacci and his colleagues recently analysed a suite of cosmological computer simulations and the galaxy interactions in them. In particular they analysed the history of galaxy halos as they evolved following a merger event. They concluded that six to ten Billion years ago the Milky Way merged in a head- on collision with a dwarf galaxy containing stars amounting to about one-to-ten billion solar masses, and that this collision could produce the character changes in stellar populations currently observed in the Milky Way’s stellar halo. -

Curriculum Vitae Avishay Gal-Yam

January 27, 2017 Curriculum Vitae Avishay Gal-Yam Personal Name: Avishay Gal-Yam Current address: Department of Particle Physics and Astrophysics, Weizmann Institute of Science, 76100 Rehovot, Israel. Telephones: home: 972-8-9464749, work: 972-8-9342063, Fax: 972-8-9344477 e-mail: [email protected] Born: March 15, 1970, Israel Family status: Married + 3 Citizenship: Israeli Education 1997-2003: Ph.D., School of Physics and Astronomy, Tel-Aviv University, Israel. Advisor: Prof. Dan Maoz 1994-1996: B.Sc., Magna Cum Laude, in Physics and Mathematics, Tel-Aviv University, Israel. (1989-1993: Military service.) Positions 2013- : Head, Physics Core Facilities Unit, Weizmann Institute of Science, Israel. 2012- : Associate Professor, Weizmann Institute of Science, Israel. 2008- : Head, Kraar Observatory Program, Weizmann Institute of Science, Israel. 2007- : Visiting Associate, California Institute of Technology. 2007-2012: Senior Scientist, Weizmann Institute of Science, Israel. 2006-2007: Postdoctoral Scholar, California Institute of Technology. 2003-2006: Hubble Postdoctoral Fellow, California Institute of Technology. 1996-2003: Physics and Mathematics Research and Teaching Assistant, Tel Aviv University. Honors and Awards 2012: Kimmel Award for Innovative Investigation. 2010: Krill Prize for Excellence in Scientific Research. 2010: Isreali Physical Society (IPS) Prize for a Young Physicist (shared with E. Nakar). 2010: German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) ARCHES Prize. 2010: Levinson Physics Prize. 2008: The Peter and Patricia Gruber Award. 2007: European Union IRG Fellow. 2006: “Citt`adi Cefal`u"Prize. 2003: Hubble Fellow. 2002: Tel Aviv U. School of Physics and Astronomy award for outstanding achievements. 2000: Colton Fellow. 2000: Tel Aviv U. School of Physics and Astronomy research and teaching excellence award. -

On the Nature of Filaments of the Large-Scale Structure of the Universe Irina Rozgacheva, I Kuvshinova

On the nature of filaments of the large-scale structure of the Universe Irina Rozgacheva, I Kuvshinova To cite this version: Irina Rozgacheva, I Kuvshinova. On the nature of filaments of the large-scale structure of the Universe. 2018. hal-01962100 HAL Id: hal-01962100 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01962100 Preprint submitted on 20 Dec 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. On the nature of filaments of the large-scale structure of the Universe I. K. Rozgachevaa, I. B. Kuvshinovab All-Russian Institute for Scientific and Technical Information of Russian Academy of Sciences (VINITI RAS), Moscow, Russia e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Observed properties of filaments which dominate in large-scale structure of the Universe are considered. A part from these properties isn’t described within the standard ΛCDM cosmological model. The “toy” model of forma- tion of primary filaments owing to the primary scalar and vector gravitational perturbations in the uniform and isotropic cosmological model which is filled with matter with negligible pressure, without use of a hypothesis of tidal interaction of dark matter halos is offered. -

The Large Scale Universe As a Quasi Quantum White Hole

International Astronomy and Astrophysics Research Journal 3(1): 22-42, 2021; Article no.IAARJ.66092 The Large Scale Universe as a Quasi Quantum White Hole U. V. S. Seshavatharam1*, Eugene Terry Tatum2 and S. Lakshminarayana3 1Honorary Faculty, I-SERVE, Survey no-42, Hitech city, Hyderabad-84,Telangana, India. 2760 Campbell Ln. Ste 106 #161, Bowling Green, KY, USA. 3Department of Nuclear Physics, Andhra University, Visakhapatnam-03, AP, India. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration among all authors. Author UVSS designed the study, performed the statistical analysis, wrote the protocol, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Authors ETT and SL managed the analyses of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information Editor(s): (1) Dr. David Garrison, University of Houston-Clear Lake, USA. (2) Professor. Hadia Hassan Selim, National Research Institute of Astronomy and Geophysics, Egypt. Reviewers: (1) Abhishek Kumar Singh, Magadh University, India. (2) Mohsen Lutephy, Azad Islamic university (IAU), Iran. (3) Sie Long Kek, Universiti Tun Hussein Onn Malaysia, Malaysia. (4) N.V.Krishna Prasad, GITAM University, India. (5) Maryam Roushan, University of Mazandaran, Iran. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sdiarticle4.com/review-history/66092 Received 17 January 2021 Original Research Article Accepted 23 March 2021 Published 01 April 2021 ABSTRACT We emphasize the point that, standard model of cosmology is basically a model of classical general relativity and it seems inevitable to have a revision with reference to quantum model of cosmology. Utmost important point to be noted is that, ‘Spin’ is a basic property of quantum mechanics and ‘rotation’ is a very common experience. -

Revisiting the Cooling Flow Problem in Galaxies, Groups, and Clusters of Galaxies

Revisiting the Cooling Flow Problem in Galaxies, Groups, and Clusters of Galaxies The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation McDonald, Michael et. al., "Revisiting the Cooling Flow Problem in Galaxies, Groups, and Clusters of Galaxies." Astrophysical Journal 858, 1 (May 2018): no. 45 doi. 10.3847/1538-4357/AABACE ©2018 Authors As Published 10.3847/1538-4357/AABACE Publisher American Astronomical Society Version Final published version Citable link https://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/125311 Terms of Use Article is made available in accordance with the publisher's policy and may be subject to US copyright law. Please refer to the publisher's site for terms of use. The Astrophysical Journal, 858:45 (15pp), 2018 May 1 https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/aabace © 2018. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Revisiting the Cooling Flow Problem in Galaxies, Groups, and Clusters of Galaxies M. McDonald1 , M. Gaspari2,5 , B. R. McNamara3 , and G. R. Tremblay4 1 Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Astrophysical Sciences, Princeton University, 4 Ivy Lane, Princeton, NJ 08544-1001, USA 3 Department of Physics & Astronomy, University of Waterloo, Canada 4 Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden Street, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA Received 2018 January 6; revised 2018 March 13; accepted 2018 March 27; published 2018 May 3 Abstract We present a study of 107 galaxies, groups, and clusters spanning ∼3 orders of magnitude in mass, ∼5 orders of magnitude in central galaxy star formation rate (SFR), ∼4 orders of magnitude in the classical cooling rate (MMrrt˙ coolº< gas() cool cool) of the intracluster medium (ICM), and ∼5 orders of magnitude in the central black hole accretion rate. -

Joint Astrophysics Nascent Universe Satellite:. Utilizing Grbs As High Redshift Probes

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Physics Scholarship Physics 2012 Joint Astrophysics Nascent Universe Satellite:. utilizing GRBs as high redshift probes P. W. A. Roming Southwest Research Institute S. G. Bilen Pennsylvania State University - Main Campus D. N. Burrows Pennsylvania State University - Main Campus A Falcone University of New Hampshire - Main Campus D. B. Fox Pennsylvania State University - Main Campus See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/physics_facpub Part of the Astrophysics and Astronomy Commons Recommended Citation Roming, P. W. A., S. G. Bilen, D. N. Burrows, A. D. Falcone, D. B. Fox, T. L. Herter, J. A. Kennea, M. L. McConnell, J. A. Nousek. JOINT ASTROPHYSICS NASCENT UNIVERSE SATELLITE:. UTILIZING GRBS AS HIGH REDSHIFT PROBES. 2012, Memorie della Societa Astronomica Italiana Supplement, 21, pp.155-161. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Physics at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Physics Scholarship by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors P. W. A. Roming, S. G. Bilen, D. N. Burrows, A Falcone, D. B. Fox, T. L. Herter, J. A. Kennea, Mark L. McConnell, and J. A. Nousek This article is available at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository: https://scholars.unh.edu/ physics_facpub/348 Mem. S.A.It. Suppl. Vol. 21, 155 Memorie della c SAIt 2012 Supplementi Joint Astrophysics Nascent Universe Satellite: utilizing GRBs as high redshift probes P. -

The Luminosity Function of the Milky Way Satellites

Draft version June 3, 2018 A Preprint typeset using LTEX style emulateapj v. 02/07/07 THE LUMINOSITY FUNCTION OF THE MILKY WAY SATELLITES S. Koposov1,2, V. Belokurov2, N.W. Evans2, P.C. Hewett2, M.J. Irwin2, G. Gilmore2, D.B. Zucker2, H.-W. Rix1, M. Fellhauer2, E.F. Bell1, E.V. Glushkova3 Draft version June 3, 2018 ABSTRACT We quantify the detectability of stellar Milky Way satellites in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) Data Release 5. We show that the effective search volumes for the recently discovered SDSS–satellites depend strongly on their luminosity, with their maximum distance, Dmax, substantially smaller than the Milky Way halo’s virial radius. Calculating the maximum accessible volume, Vmax, for all faint detected satellites, allows the calculation of the luminosity function for Milky Way satellite galaxies, accounting quantitatively for their detectability. We find that the number density of satellite galaxies continues to rise towards low luminosities, but may flatten at MV 5; within the uncertainties, the ∼− 0.1(MV +5) luminosity function can be described by a single power law dN/dMV = 10 10 , spanning × luminosities from MV = 2 all the way to the luminosity of the Large Magellanic Cloud. Comparing these results to several semi-analytic− galaxy formation models, we find that their predictions differ significantly from the data: either the shape of the luminosity function, or the surface brightness distributions of the models, do not match. Subject headings: Galaxy: halo – Galaxy: structure – Galaxy: formation – Local Group 1. INTRODUCTION ing satellite” problem. First identified by Klypin et al. In Cold Dark Matter (CDM) models, large spiral (1999) and Moore et al. -

And Ecclesiastical Cosmology

GSJ: VOLUME 6, ISSUE 3, MARCH 2018 101 GSJ: Volume 6, Issue 3, March 2018, Online: ISSN 2320-9186 www.globalscientificjournal.com DEMOLITION HUBBLE'S LAW, BIG BANG THE BASIS OF "MODERN" AND ECCLESIASTICAL COSMOLOGY Author: Weitter Duckss (Slavko Sedic) Zadar Croatia Pусскй Croatian „If two objects are represented by ball bearings and space-time by the stretching of a rubber sheet, the Doppler effect is caused by the rolling of ball bearings over the rubber sheet in order to achieve a particular motion. A cosmological red shift occurs when ball bearings get stuck on the sheet, which is stretched.“ Wikipedia OK, let's check that on our local group of galaxies (the table from my article „Where did the blue spectral shift inside the universe come from?“) galaxies, local groups Redshift km/s Blueshift km/s Sextans B (4.44 ± 0.23 Mly) 300 ± 0 Sextans A 324 ± 2 NGC 3109 403 ± 1 Tucana Dwarf 130 ± ? Leo I 285 ± 2 NGC 6822 -57 ± 2 Andromeda Galaxy -301 ± 1 Leo II (about 690,000 ly) 79 ± 1 Phoenix Dwarf 60 ± 30 SagDIG -79 ± 1 Aquarius Dwarf -141 ± 2 Wolf–Lundmark–Melotte -122 ± 2 Pisces Dwarf -287 ± 0 Antlia Dwarf 362 ± 0 Leo A 0.000067 (z) Pegasus Dwarf Spheroidal -354 ± 3 IC 10 -348 ± 1 NGC 185 -202 ± 3 Canes Venatici I ~ 31 GSJ© 2018 www.globalscientificjournal.com GSJ: VOLUME 6, ISSUE 3, MARCH 2018 102 Andromeda III -351 ± 9 Andromeda II -188 ± 3 Triangulum Galaxy -179 ± 3 Messier 110 -241 ± 3 NGC 147 (2.53 ± 0.11 Mly) -193 ± 3 Small Magellanic Cloud 0.000527 Large Magellanic Cloud - - M32 -200 ± 6 NGC 205 -241 ± 3 IC 1613 -234 ± 1 Carina Dwarf 230 ± 60 Sextans Dwarf 224 ± 2 Ursa Minor Dwarf (200 ± 30 kly) -247 ± 1 Draco Dwarf -292 ± 21 Cassiopeia Dwarf -307 ± 2 Ursa Major II Dwarf - 116 Leo IV 130 Leo V ( 585 kly) 173 Leo T -60 Bootes II -120 Pegasus Dwarf -183 ± 0 Sculptor Dwarf 110 ± 1 Etc. -

Exploring Dust Extinction at the Edge of Reionization

Draft version October 15, 2018 Preprint typeset using LATEX style emulateapj v. 11/10/09 EXPLORING DUST EXTINCTION AT THE EDGE OF REIONIZATION Tayyaba Zafar,1 Darach J. Watson,1 Nial R. Tanvir,2 Johan P. U. Fynbo,1 Rhaana L.C.Starling,2 and Andrew J. Levan3 Draft version October 15, 2018 ABSTRACT The brightness of gamma-ray burst (GRB) afterglows and their occurrence in young, blue galaxies make them excellent probes to study star forming regions in the distant Universe. We here elucidate dust extinction properties in the early Universe through the analysis of the afterglows of all known z > 6 GRBs: GRB090423, 080913 and 050904, at z = 8.2, 6.69, and 6.295, respectively. We gather all available optical and near-infrared photometry, spectroscopy and X-ray data to construct spectral energy distributions (SEDs) at multiple epochs. We then fit the SEDs at all epochs with a dust-attenuated power-law or broken power-law. We find no evidence for dust extinction in GRB050904 and GRB090423, with possible evidence for a low level of extinction in GRB080913. We compare the high redshift GRBs to a sample of lower redshift GRB extinctions and find a lack of even moderately extinguished events (AV ∼ 0.3) above z & 4. In spite of the biased selection and small number statistics, this result hints at a decrease in dust content in star-forming environments at high redshifts. Subject headings: dark ages, reionization, first stars – dust, extinction – galaxies: high-redshift – gamma-ray burst: individual (GRB090423, 080913, and 050904) 1. INTRODUCTION ing made in the rest frame UV, they are in principle relatively Dust formationin the early universeis a hotly debated topic. -

The Evolution of Galaxy Structure Over Cosmic Time

Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophy. 2014 1056-8700/97/0610-00 The Evolution of Galaxy Structure over Cosmic Time Christopher J. Conselice Centre for Astronomy and Particle Theory School of Physics and Astronomy University of Nottingham, United Kingdom Key Words galaxy evolution, galaxy morphology, galaxy structure Abstract I present a comprehensive review of the evolution of galaxy structure in the universe from the first galaxies we can currently observe at z ∼ 6 down to galaxies we see in the local universe. I further address how these changes reveal galaxy formation processes that only galaxy structural analyses can provide. This review is pedagogical and begins with a de- tailed discussion of the major methods in which galaxies are studied morphologically and structurally. This includes the well-established visual method for morphology; S´ersic fitting to measure galaxy sizes and surface brightness profile shapes; non-parametric structural methods including the concentration (C), asymmetry (A), clumpiness (S) (CAS) method, the Gini/M20 parameters, as well as newer structural indices. Included is a discussion of how these structural indices measure fundamental properties of galaxies such as their scale, star formation rate, and ongoing merger activity. Extensive observational results are shown demonstrating how broad galaxy morphologies and structures change with time up to z ∼ 3, from small, compact and peculiar systems in the distant universe to the formation of the Hubble sequence dominated by spirals and ellipticals we find today. This review further addresses how structural methods accurately identify galaxies in mergers, and allow mea- arXiv:1403.2783v1 [astro-ph.GA] 12 Mar 2014 surements of the merger history out to z ∼ 3. -

An Introduction to Our Universe

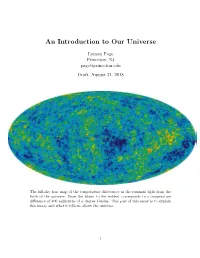

An Introduction to Our Universe Lyman Page Princeton, NJ [email protected] Draft, August 31, 2018 The full-sky heat map of the temperature differences in the remnant light from the birth of the universe. From the bluest to the reddest corresponds to a temperature difference of 400 millionths of a degree Celsius. The goal of this essay is to explain this image and what it tells us about the universe. 1 Contents 1 Preface 2 2 Introduction to Cosmology 3 3 How Big is the Universe? 4 4 The Universe is Expanding 10 5 The Age of the Universe is Finite 15 6 The Observable Universe 17 7 The Universe is Infinite ?! 17 8 Telescopes are Like Time Machines 18 9 The CMB 20 10 Dark Matter 23 11 The Accelerating Universe 25 12 Structure Formation and the Cosmic Timeline 26 13 The CMB Anisotropy 29 14 How Do We Measure the CMB? 36 15 The Geometry of the Universe 40 16 Quantum Mechanics and the Seeds of Cosmic Structure Formation. 43 17 Pulling it all Together with the Standard Model of Cosmology 45 18 Frontiers 48 19 Endnote 49 A Appendix A: The Electromagnetic Spectrum 51 B Appendix B: Expanding Space 52 C Appendix C: Significant Events in the Cosmic Timeline 53 D Appendix D: Size and Age of the Observable Universe 54 1 1 Preface These pages are a brief introduction to modern cosmology. They were written for family and friends who at various times have asked what I work on. The goal is to convey a geometrical picture of how to think about the universe on the grandest scales.