Internal Migration in Shahjahanpur District a Socio-Economic and Structural Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CP Vol VIII EIA

GOVERNMENT OF UTTAR PRADESH Public Works Department Uttar Pradesh Core Road Network Development Program Part – A: Project Preparation DETAILED PROJECT REPORT Volume - VIII: Environmental Impact Assessment Report and Environmental Management Plan Gola – Shahjahanpur Road (SH-93) July 2015 India Consulting engineers pvt. ltd. Uttar Pradesh Core Road Network Development Program DETAILED PROJECT REPORT Volume-VIII: EIA and EMP Report Gola – Shahjahanpur Road (SH-93) Volume-VIII : Environmental Impact Assessment Report (EIA) and Document Name Environmental Management Plan (EMP) (Detailed Project Report) Document Number EIRH1UP020/DPR/SH-93/GS/004/VIII Uttar Pradesh Core Road Network Development Program Project Name Part – A: Project Preparation including Detailed Engineering Design and Contract Documentation Project Number EIRH1UP020 Document Authentication Name Designation Prepared by Dr. S.S. Deepak Environmental Specialist Reviewed by Sudhendra Kumar Karanam Sr. General Manager (Roads & Highways) Rajeev Kumar Gupta Deputy Team Leader Avadesh Singh Technical Head Approved by Rick Camise Team Leader History of Revisions Version Date Description of Change(s) Rev. 0 19/12/2014 First Submission Rev. 1 29/12/2014 Second Submission after incorporating World Bank’s Comments and Suggestions Rev. 2 13/01/2015 Incorporating World Bank’s Comments and Suggestions Rev. 3 16/07/2015 Revision after discussion with Independent Consultant Page i| Rev: R3 , Uttar Pradesh Core Road Network Development Program DETAILED PROJECT REPORT Volume-VIII: EIA and EMP -

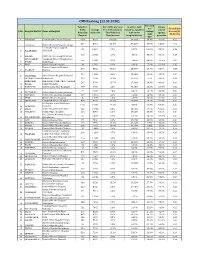

CMS Ranking (12.03.2020) Percentil Total Pre- Percentile of ( % of % of Pre-Auth Claims E of Consolidate Auths Average Pre‐Auth Raised Vs Raised Vs

CMS Ranking (12.03.2020) Percentil Total Pre- Percentile of ( % of % of Pre-Auth Claims e of Consolidate Auths Average Pre-Auth raised vs raised vs. total Pre- raised S.No. Hospital District Name of Hospital average d score (30- Raised by claim size Total District) Auth in the against claim 30-30-10) Hospital Beneficiaries hospital district preauths size 1 VARANASI Homi Bhabha Cancer Hospital 4456 8325 100.0% 16.61% 36.3% 92.1% 0.55 560 8691 31.3% 37.31% 37.9% 98.8% 0.42 2 LALITPUR District Female Hospital Lalitpur Tej Bhadur Sapru Hospital 81 22910 1.3% 0.58% 100.0% 88.9% 0.39 3 ALLAHABAD Allahabad 123 20157 2.1% 4.54% 88.0% 98.4% 0.38 4 HARDOI District Female Hospital Hardoi SANT KABEER Combined District Hospital Sant 66 19332 3.1% 2.65% 84.4% 100.0% 0.37 5 NAGAR Kabir Nagar 6 MAU Distric Female Hospital 39 17641 1.6% 6.31% 77.0% 100.0% 0.35 District Combined Hospital 374 6352 41.5% 15.56% 27.7% 98.9% 0.35 7 BAGHPAT Baghpat 204 14262 3.9% 15.94% 62.3% 98.5% 0.34 8 RAE BARELI Rbms District Hospital Raebareli 9 SIDDHARTH NAGADchsdr.001 305 2089 10.3% 62.37% 9.1% 98.0% 0.34 AMBEDKAR Mmahatma Jyotiba Phule Combind 517 8784 15.7% 27.33% 38.3% 98.6% 0.34 10 NAGAR District Hospital 11 HAMIRPUR Distt Hospital Male Hamirpur 107 5786 6.2% 43.15% 25.3% 100.0% 0.32 72 16992 2.3% 3.37% 74.2% 83.3% 0.32 12 SULTANPUR District Male Hospital Sultanpur 13 FAIZABAD District Haopita Male Faizabad 117 15746 3.2% 2.65% 68.7% 97.4% 0.32 14 ETAH District Women Hospital 5 17875 0.3% 0.77% 78.0% 80.0% 0.32 15 SHRAVASTI Combined District Hospital 484 3224 31.6% -

Ubrief Industrial Profile of Shahjahanpur District

Government of India Ministry of MSME BriefU Industrial Profile of Shahjahanpur District U.P MSME-Development Institute (Ministry of MSME, Govt. of India,) Phone: 0512-2295070-73 Fax: 0512-2240143 E-mail : [email protected] Web- msmedikanpur.gov.in 1 FOREWORD District Industrial Potentiality Survey Report of District Shahjahnpur is a key report which not only contains current industrial scenario of the district but also other useful information about the district. This report provides valuable inputs which may be useful for existing & prospective entrepreneurs of the District. It is the only source which provides the latest data on infrastructure, banking and industry of the district. It also provides information on potentials areas in manufacturing and service sector of the district. District Administration, District Industries and Enterprise Promotion Centre, Shahjahanpur, Statistical Department, Agriculture & Horticulture Offices, District Lead Bank, Live Stock Office and other departments of Shahjahanpur and Lucknow have provided valuable information via journal, website, telephonic conversation and other communication channels. I sincerely hope that District Industrial Potentiality Survey Report of District Shahjahanpur will facilitate easier dissemination of information about the district to policy makers and also to the professionals working in the MSME sector. I appreciate the efforts made by Shri Vijay Kumar Bhatt, Asstt. Director (Stat.) in preparing the District Industrial Potentiality Survey Report of Shahjahnpur District. June, 2016 ( U. C. Shukla ) Kanpur Director 2 Contents S. No. Topic Page No. 1. General Characteristics of the District 03 1.1 Location & Geographical Area 03 1.2 Topography 03 1.3 Availability of Minerals. 04 1.4 Forest 04 1.5 Administrative set up 04 2. -

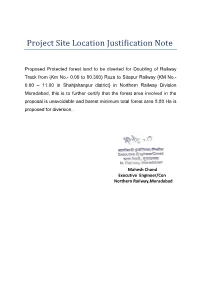

Project Site Location Justification Note

Project Site Location Justification Note Proposed Protected forest land to be diverted for Doubling of Railway Track from (Km No.- 0.00 to 80.300) Roza to Sitapur Railway {KM No.- 0.00 – 11.00 in Shahjahanpur district} in Northern Railway Division Moradabad, this is to further certify that the forest area involved in the proposal is unavoidable and barest minimum total forest area 8.80 Ha is proposed for diversion. Mahesh Chand Executive Engineer/Con Northern Railway,Moradabad Project Site Location Justification Note Proposed Protected forest land to be diverted for Doubling of Railway Track from (Km No.- 0.00 to 80.30) Roza to Sitapur Railway {KM No.- 11.00 to 28.00 & 34.00 to 46.00 in Lakhimpur Kheri district} in Northern Railway Division Moradabad, this is to further certify that the forest area involved in the proposal is unavoidable and barest minimum total forest area 24.06 Ha is proposed for diversion. Mahesh Chand Executive Engineer/Con Northern Railway,Moradabad Project Site Location Justification Note Proposed Protected forest land to be diverted for Doubling of Railway Track from (Km No.- 0.00 to 80.30) Roza to Sitapur Railway {KM No.- 28.00 to 34.00 in Hardoi district} in Northern Railway Division Moradabad, this is to further certify that the forest area involved in the proposal is unavoidable and barest minimum total forest area 6.1133 Ha is proposed for diversion. Mahesh Chand Executive Engineer/Con Northern Railway,Moradabad Project Site Location Justification Note Proposed Protected forest land to be diverted for Doubling of Railway Track from (Km No.- 0.00 to 80.30) Roza to Sitapur Railway {KM No.- 46.00 to 80.30 in Sitapur district} in Northern Railway Division Moradabad, this is to further certify that the forest area involved in the proposal is unavoidable and barest minimum total forest area 30.6259 Ha is proposed for diversion. -

Uttar Pradesh

DLHS -2 DLHS-2 Uttar Pradesh Reproductive and Child Health District Level Household Survey 2002-04 International Institute for Ministry of Health & Family TNS India Private Limited Population Sciences Welfare, Government of India New Delhi – 110 016 (Deemed University) New Delhi – 110 011 Mumbai – 400 088 Reproductive and Child Health District Level Household Survey (DLHS - 2) Uttar Pradesh 2002-04 International Institute for Ministry of Health & Family Population Sciences, Welfare, Government of India, TNS India Pvt. Ltd., (Deemed University) New Delhi – 110 011 New Delhi – 110 016 Mumbai – 400 088 Contributors TNS India Private Limited, New Delhi Tilak Mukherji U.V.Somayajulu S. Anil Chandran B. S. Singh International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai F. Ram B. Paswan L. Ladu Singh Rajiv Ranjan Akash Wankhede CONTENTS Page Tables ................................................................................................................................ iv Figures ................................................................................................................................ vii Maps ................................................................................................................................... vii Preface and Acknowledgement ......................................................................................... ix Key Indicators ................................................................................................................... xi Salient Findings ................................................................................................................ -

For Award of Ph.D /D.Litt./D.Sc. DEGREE Ph.D. Fnukad 26&5&2012 Ls 18&10&2012 Rd Leiuu Gqbz Eksf[Kdh Ijh{Kkvksa

For Award of Ph.D /D.Litt./D.Sc. DEGREE fnukad 26&5&2012 ls 18&10&2012 rd lEiUu gqbZ ekSf[kdh ijh{kkvksa dk fooj.k Ph.D. Effect of Advermectins on Haematology and Enzyme Profiles of Fresh Water Fish 1 Zoology Namita Verma Dr. K.K.Saxena R-0130295 H.No.108-B,KrishnaNagar Bareilly College 26.5.2012 Izatnagar, Bareilly Bareilly. 2 Geography Jasneet Kaur Dr. R.P.Singh Patterns and Dynamics of Agricultural Land Use in Shahjahanpur District R-08112429 69-Green Park Vistar Principal, 26.5.2012 Bareilly Bareilly College.Bareilly 3 Economics Sandhya Jaiswal Dr. N.L.Sharma mRrj izns'k dh ifjogu O;oLFkk dk fo'ys"k.kkRed v/;;u R-06113623 245-Bagh Ahmad Ali Bareilly College 26.5.2012 Talab, Bareilly Bareilly 4 Physics Nupur Saxena Dr, Avinash Agarwal Studies of Embedded Silicon Nanocrystals Formation by Energetic Ion Beam R-9825946 405/F, Kunwarpur(Sivpuri) Bareilly College 26.5.2012 Bareilly Bareilly 5 English Poonam Rani Dr. Santosh Agrawal The Function of Imagery in Graham Greene's Major Novels : A Critical Study R-9810296 Chauraha Gali Near Devi G.D.H.G.College 26.5.2012 Ji Ka Mandir,Moradabad Moradabad 6 Computer Sc. Mano Yadav Dr. K.V.Arya Study of Routing Issues in Mobile AD HOC Networks R-0126844 426-Beharipur Civil Lines ABV- IIITM 28.5.2012 Bareilly Gwalior 7 Education Rajeev Kumar Singh Dr. Shabhat Jeet Singh izkFkfed fo|ky;ksa esa dk;Zjr f'k{kkfe=ksa dh f'k{k.k ds izfr vfHko``fRr ,oa dk;Z larqf"V dks izHkkfor djus okys dkjdksa dk v/;;u R-0565366 D-27-9 South City S.S.College 28.5.2012 Shahjahanpur Shahjahanpur 8 Sanskrit Piyush Sharma Dr. -

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008

Copyright by Mohammad Raisur Rahman 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Mohammad Raisur Rahman certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India Committee: _____________________________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________________________ Cynthia M. Talbot _____________________________________ Denise A. Spellberg _____________________________________ Michael H. Fisher _____________________________________ Syed Akbar Hyder Islam, Modernity, and Educated Muslims: A History of Qasbahs in Colonial India by Mohammad Raisur Rahman, B.A. Honors; M.A.; M.Phil. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin August 2008 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to the fond memories of my parents, Najma Bano and Azizur Rahman, and to Kulsum Acknowledgements Many people have assisted me in the completion of this project. This work could not have taken its current shape in the absence of their contributions. I thank them all. First and foremost, I owe my greatest debt of gratitude to my advisor Gail Minault for her guidance and assistance. I am grateful for her useful comments, sharp criticisms, and invaluable suggestions on the earlier drafts, and for her constant encouragement, support, and generous time throughout my doctoral work. I must add that it was her path breaking scholarship in South Asian Islam that inspired me to come to Austin, Texas all the way from New Delhi, India. While it brought me an opportunity to work under her supervision, I benefited myself further at the prospect of working with some of the finest scholars and excellent human beings I have ever known. -

List of Class Wise Ulbs of Uttar Pradesh

List of Class wise ULBs of Uttar Pradesh Classification Nos. Name of Town I Class 50 Moradabad, Meerut, Ghazia bad, Aligarh, Agra, Bareilly , Lucknow , Kanpur , Jhansi, Allahabad , (100,000 & above Population) Gorakhpur & Varanasi (all Nagar Nigam) Saharanpur, Muzaffarnagar, Sambhal, Chandausi, Rampur, Amroha, Hapur, Modinagar, Loni, Bulandshahr , Hathras, Mathura, Firozabad, Etah, Badaun, Pilibhit, Shahjahanpur, Lakhimpur, Sitapur, Hardoi , Unnao, Raebareli, Farrukkhabad, Etawah, Orai, Lalitpur, Banda, Fatehpur, Faizabad, Sultanpur, Bahraich, Gonda, Basti , Deoria, Maunath Bhanjan, Ballia, Jaunpur & Mirzapur (all Nagar Palika Parishad) II Class 56 Deoband, Gangoh, Shamli, Kairana, Khatauli, Kiratpur, Chandpur, Najibabad, Bijnor, Nagina, Sherkot, (50,000 - 99,999 Population) Hasanpur, Mawana, Baraut, Muradnagar, Pilkhuwa, Dadri, Sikandrabad, Jahangirabad, Khurja, Vrindavan, Sikohabad,Tundla, Kasganj, Mainpuri, Sahaswan, Ujhani, Beheri, Faridpur, Bisalpur, Tilhar, Gola Gokarannath, Laharpur, Shahabad, Gangaghat, Kannauj, Chhibramau, Auraiya, Konch, Jalaun, Mauranipur, Rath, Mahoba, Pratapgarh, Nawabganj, Tanda, Nanpara, Balrampur, Mubarakpur, Azamgarh, Ghazipur, Mughalsarai & Bhadohi (all Nagar Palika Parishad) Obra, Renukoot & Pipri (all Nagar Panchayat) III Class 167 Nakur, Kandhla, Afzalgarh, Seohara, Dhampur, Nehtaur, Noorpur, Thakurdwara, Bilari, Bahjoi, Tanda, Bilaspur, (20,000 - 49,999 Population) Suar, Milak, Bachhraon, Dhanaura, Sardhana, Bagpat, Garmukteshwer, Anupshahar, Gulathi, Siana, Dibai, Shikarpur, Atrauli, Khair, Sikandra -

Annexure-V State/Circle Wise List of Post Offices Modernised/Upgraded

State/Circle wise list of Post Offices modernised/upgraded for Automatic Teller Machine (ATM) Annexure-V Sl No. State/UT Circle Office Regional Office Divisional Office Name of Operational Post Office ATMs Pin 1 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA PRAKASAM Addanki SO 523201 2 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL KURNOOL Adoni H.O 518301 3 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM AMALAPURAM Amalapuram H.O 533201 4 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Anantapur H.O 515001 5 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Machilipatnam Avanigadda H.O 521121 6 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA TENALI Bapatla H.O 522101 7 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Bhimavaram Bhimavaram H.O 534201 8 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA VIJAYAWADA Buckinghampet H.O 520002 9 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL TIRUPATI Chandragiri H.O 517101 10 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Prakasam Chirala H.O 523155 11 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CHITTOOR Chittoor H.O 517001 12 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL CUDDAPAH Cuddapah H.O 516001 13 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VISAKHAPATNAM VISAKHAPATNAM Dabagardens S.O 530020 14 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL HINDUPUR Dharmavaram H.O 515671 15 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA ELURU Eluru H.O 534001 16 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudivada Gudivada H.O 521301 17 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH Vijayawada Gudur Gudur H.O 524101 18 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH KURNOOL ANANTAPUR Guntakal H.O 515801 19 Andhra Pradesh ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA -

Project Summary

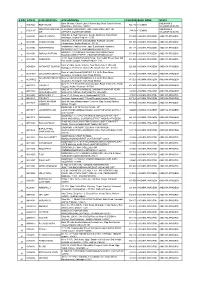

Project Summary Proposed Protected forest land to be diverted for Doubling of Railway Track from (Km No.- 0.00 to 80.30) Roza to Sitapur Railway {KM No.- 0.00 – 11.00 in Shahjahanpur district}, {KM No.- 11.00 to 28.00 & 34.00 to 46.00 in Lakhimpur Kheri district}, {KM No.- 28.00 to 34.00 in Hardoi district} and {KM No.- 46.00 to 80.30 in Sitapur district} in Northern Railway Division Moradabad. District wise details of forest land and non forest land are as follows: Sr. No. DISTRICT PROTECTED NON FOREST FOREST LAND LAND Area (in Ha) Area (in Ha) 1 Shahjahanpur 8.80 0.0175 2 Lakhimpur Kheri 24.06 0.3235 3 Hardoi 6.1133 0.0851 4 Sitapur 30.6259 0.6435 Total Area 69.5992 1.0696 Mahesh Chand Executive Engineer/Con Northern Railway,Moradabad Area Calculation Sheet Proposed Protected Forest Land to be Diverted For Proposed new 2nd line along with existing Railway line under Roza - Sitapur Railway Track (Km. no. 0.00 - 80.30) Doubling Project of Northern Railway, from Km. 0.00 to 11.00, in Moradabad Division, District: Shahjahanpur (Uttar Pradesh) Protected Forest Land Area Calculation From To Length Width Area Area Sr. No. (Km) (Km) (m) (m) (SqM) (Ha) 1 1.900 7.360 5460.00 8.00 43680.00 4.3680 2 8.670 11.000 2330.00 8.00 18640.00 1.8640 7790.00 62320.00 6.2320 Proposed Protected Forest Land Area 6.2320Ha Protected Forest Land along Railway Yards Forest Land Area Calculation From To Length Width Area Area Sr. -

S No Atm Id Atm Location Atm Address Pincode Bank

S NO ATM ID ATM LOCATION ATM ADDRESS PINCODE BANK ZONE STATE Bank Of India, Church Lane, Phoenix Bay, Near Carmel School, ANDAMAN & ACE9022 PORT BLAIR 744 101 CHENNAI 1 Ward No.6, Port Blair - 744101 NICOBAR ISLANDS DOLYGUNJ,PORTBL ATR ROAD, PHARGOAN, DOLYGUNJ POST,OPP TO ANDAMAN & CCE8137 744103 CHENNAI 2 AIR AIRPORT, SOUTH ANDAMAN NICOBAR ISLANDS Shop No :2, Near Sai Xerox, Beside Medinova, Rajiv Road, AAX8001 ANANTHAPURA 515 001 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 3 Anathapur, Andhra Pradesh - 5155 Shop No 2, Ammanna Setty Building, Kothavur Junction, ACV8001 CHODAVARAM 531 036 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 4 Chodavaram, Andhra Pradesh - 53136 kiranashop 5 road junction ,opp. Sudarshana mandiram, ACV8002 NARSIPATNAM 531 116 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 5 Narsipatnam 531116 visakhapatnam (dist)-531116 DO.NO 11-183,GOPALA PATNAM, MAIN ROAD NEAR ACV8003 GOPALA PATNAM 530 047 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 6 NOOKALAMMA TEMPLE, VISAKHAPATNAM-530047 4-493, Near Bharat Petroliam Pump, Koti Reddy Street, Near Old ACY8001 CUDDAPPA 516 001 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 7 Bus stand Cudappa, Andhra Pradesh- 5161 Bank of India, Guntur Branch, Door No.5-25-521, Main Rd, AGN9001 KOTHAPET GUNTUR 522 001 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta, P.B.No.66, Guntur (P), Dist.Guntur, AP - 522001. 8 Bank of India Branch,DOOR NO. 9-8-64,Sri Ram Nivas, AGW8001 GAJUWAKA BRANCH 530 026 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH 9 Gajuwaka, Anakapalle Main Road-530026 GAJUWAKA BRANCH Bank of India Branch,DOOR NO. 9-8-64,Sri Ram Nivas, AGW9002 530 026 ANDHRA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH -

District Census Handbook, Pilibhit, Part XIII-A, Series-22, Uttar Pradesh

CENSUS 1981 '1T'l XIII - at f;~/SERiES-22 111'1' ~et i!"~ \i~'{ • f;(~~;:ft UTTAR PRADESH Part XIII- A VILLAGE & TOWN DIRECTORY ~~T Mt11 . ql~;ftt{ffi "'141°'''1 DISTRICT .~ ~fa~ft€1~T p~mHIT DISTRICTo CENSUS HANDBOOK '(1ft;r 1lca', 11'~ ~mijf.;Cfl ~ f~, \If'''~lijl'lT qf"{'qTin.t, ~"{ riI8' I i . $ffficrfr i-ii 2. Sf rCfofi~<f v-vi 3. f~ 'fiT ifT;;f'q~ 4. f~ ~ ~~q'fIl aIT~ ix -xi 5. f~T <5FfiTUf'ir ~~('f~fhr<fiT <fiT qf~ xiii-vxi 6. f<nl~lr(Jmqcp fgctf1lTf' \'~i ~\Jf1 ~) 1-11 7. aTimiJ' - I 'llTlf f~fuotlT a~€r~ : I-tfimmn 0) ~m{1 ifRf'ifi;l" (ii) ;XT+rT"liT qlll~ ~T 14-18 (iii) ;Xli{ frr~fwCfiT 24-71 2-.1~~ (i) a~ij'ffi l1T<ff:em Oi) ;XT'1T"lif' qOf~ij ~"tT 74-78 (iii) ~Tl1 frritf'W'liT 84-131 !-~~~~ (i) ~ijT~ ifr.rf~ (ii) lJr'1T!fiT q1J{~l1 ~r 134-137 (iii) <JTl1 rim!ITCfiT 142-181 qf~f~ I f!1TeTT, f:qfCficm 8t'tt ar~ ~flf&Tat"f 'fiT a~ijl'{1cfl~ ~T~ 184 -181~ II \;f<fifOf<rT SPtT\ifYT ~ <{<["{ t1rit qlt 'fif'-T, l~~U el~), \ifiiilVTrrT 'iil'-T ifi ~f1T ra-q~T'f ~q.:tlf' BTTCfif ISS III ~\Jf~!fiT ~~1: 'EIfcnn l:f~ lATllT ~ \i;:q"t 1. r:ft{1Tma- 189-193 2. ~«~$'{ 194-197 3. ~~~ 198-202 VI ~~f'ifa ijfrfcrIT 51!:fT BT2~f"qa' 6Rijftfa'll"Y SP"t i5Fr~T CfiT ~t>I' ;jf;:r~itfT ~ ~q"m qf~U"{ ~ ~UT"{ <JIlTY !fif' ~'ift I (at) ~:qn 'itlf~T 1.