Further Assessment of Matters Under the Regional Forest Agreements Act 2002 (Cth) Relating to the 2017 Variation of the Tasmanian Regional Forest Agreement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A REVISION of TRISETUM Victor L. Finot,' Paul M

A REVISION OF TRISETUM Victor L. Finot,' Paul M. Peterson,3 (POACEAE: POOIDEAE: Fernando 0 Zuloaga,* Robert J. v sorene, and Oscar Mattnei AVENINAE) IN SOUTH AMERICA1 ABSTRACT A taxonomic treatment of Trisetum Pers. for South America, is given. Eighteen species and six varieties of Trisetum are recognized in South America. Chile (14 species, 3 varieties) and Argentina (12 species, 5 varieties) have the greatest number of taxa in the genus. Two varieties, T. barbinode var. sclerophyllum and T longiglume var. glabratum, are endemic to Argentina, whereas T. mattheii and T nancaguense are known only from Chile. Trisetum andinum is endemic to Ecuador, T. macbridei is endemic to Peru, and T. foliosum is endemic to Venezuela. A total of four species are found in Ecuador and Peru, and there are two species in Venezuela and Colombia. The following new species are described and illustrated: Trisetum mattheii Finot and T nancaguense Finot, from Chile, and T pyramidatum Louis- Marie ex Finot, from Chile and Argentina. The following two new combinations are made: T barbinode var. sclerophyllum (Hack, ex Stuck.) Finot and T. spicatum var. cumingii (Nees ex Steud.) Finot. A key for distinguishing the species and varieties of Trisetum in South America is given. The names Koeleria cumingii Nees ex Steud., Trisetum sect. Anaulacoa Louis-Marie, Trisetum sect. Aulacoa Louis-Marie, Trisetum subg. Heterolytrum Louis-Marie, Trisetum subg. Isolytrum Louis-Marie, Trisetum subsect. Koeleriformia Louis-Marie, Trisetum subsect. Sphenopholidea Louis-Marie, Trisetum ma- lacophyllum Steud., Trisetum variabile E. Desv., and Trisetum variabile var. virescens E. Desv. are lectotypified. Key words: Aveninae, Gramineae, Poaceae, Pooideae, Trisetum. -

Full Article

Volume 3(4): 599 TELOPEA Publication Date: 12 April 1990 Til. Ro)'al BOTANIC GARDENS dx.doi.org/10.7751/telopea19904909 Journal of Plant Systematics 6 DOPII(liPi Tm st plantnet.rbgsyd.nsw.gov.au/Telopea • escholarship.usyd.edu.au/journals/index.php/TEL· ISSN 0312-9764 (Print) • ISSN 2200-4025 (Online) Telopea Vol. 3(4): 599 (1990) 599 SHORT COMMUNICATION Amphibromus nervosus (Poaceae), an earlier combination and further synonyms Arthur Chapman, Bureau of Flora & Fauna, Canberra, has kindly pointed out to me that the combination Amphibromus nervosus (J. D. Hook.) Baillon had been made in 1893, earlier than the combination made by G. C. Druce re ported in our revision of the genus Amphibromus in Australia (Jacobs and Lapinpuro 1986). Baillon's combination had been overlooked by Index Kewensis and by the Chase Index (Chase and Niles 1962). The full citation is: Amphibromus nervosus (J. D. Hook.) Baillon, Histoire des Plantes 12: 203 (1893). BASIONYM: Danthonia nervosa J. D. Hook., Fl.FI. Tasm. 2: 121, pI.pl. 163A (1858). Hooker based his combination on the illegitimate Avena nervosa R. Br. (see Jacobs and Lapinpuro 1986 for further comment). Amphibromus nervosus (1. D. Hook.) G. C. Druce then becomes a superfluous combina tion and is added to the synonymy. Arthur Chapman also kindly pointed out a synonym that to the best of my knowledge has not been used beyond its initial publication. This synonym is: Avenastrum nervosum Vierh., Verhandlungen der Gesellschaft Deutscher Naturforscher und Artze 85. Versammlung zu Wien (Leipzig) 1: 672 (1913). This name was based on the illegitimate Avena nervosa R. -

Aspects of the Distribution, Phytosociology, Ecology and Management of Danthonia Popinensis 0.1. Morris, an Endangered Wallaby Grass from Tasmania

Papers and Proceedings o/the Royal Society o/Tasmania, Volume 131, 1997 31 ASPECTS OF THE DISTRIBUTION, PHYTOSOCIOLOGY, ECOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT OF DANTHONIA POPINENSIS 0.1. MORRIS, AN ENDANGERED WALLABY GRASS FROM TASMANIA by Louise Gilfedder and J.B. Kirkpatrick (with four tables and two text-figures) GILFEDDER, LOUISE & KIRKPATRICK, ]. B., 1997 (31 :viii): Aspects of the distribution, phytosociology, ecology and management of Danthonia popinensis D.1. Morris, an endangered wallaby grass from Tasmania. ISSN 0080-4703. Pap. Proc. R. Soc. Tasm. 131: 31-35. Parks and Wildlife Service, GPO Box 44A Hobart, Tasmania, Australia 7001, formerly Department of Geography and Environmental Studies (LG); Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, University of Tasmania, GPO Box 252- 78, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia 7001 GBK). Danthonia popinensis is a recently discovered, nationally endangered tussock grass, originally known from only one roadside population at Kempton, Tasmania. Six populations have been recorded, all from flat land with mildly acid non-rocky soils, and all in small toadside or paddock remnants, badly invaded by exotic plants. However, one site has recently been destroyed through roadworks. The species germinates best at temperatures of 10°e, indicating a winter germination strategy. Autumn burning at Kempton resulted in an increased cover of D. popinensis two years after the burn, but also resulted in an increased cover of competitive exotics. The future of the species needs to be secured by ex situ plantings, as almost all of its original habitat has been converted to crops or improved pasture. Key Words: Danthonia popinensis, wallaby grass, tussock grass, endangered species, Tasmania. INTRODUCTION common fire management regime (e.g. -

Threatened Species Protection Act 1995

Contents (1995 - 83) Threatened Species Protection Act 1995 Long Title Part 1 - Preliminary 1. Short title 2. Commencement 3. Interpretation 4. Objectives to be furthered 5. Administration of public authorities 6. Crown to be bound Part 2 - Administration 7. Functions of Secretary 8. Scientific Advisory Committee 9. Community Review Committee Part 3 - Conservation of Threatened Species Division 1 - Threatened species strategy 10. Threatened species strategy 11. Procedure for making strategy 12. Amendment and revocation of strategy Division 2 - Listing of threatened flora and fauna 13. Lists of threatened flora and fauna 14. Notification by Minister and right of appeal 15. Eligibility for listing 16. Nomination for listing 17. Consideration of nomination by SAC 18. Preliminary recommendation by SAC 19. Final recommendation by SAC 20. CRC to be advised of public notification 21. Minister's decision Division 3 - Listing statements 22. Listing statements Division 4 - Critical habitats 23. Determination of critical habitats 24. Amendment and revocation of determinations Division 5 - Recovery plans for threatened species 25. Recovery plans 26. Amendment and revocation of recovery plans Division 6 - Threat abatement plans 27. Threat abatement plans 28. Amendment and revocation of threat abatement plans Division 7 - Land management plans and agreements 29. Land management plans 30. Agreements arising from land management plans 31. Public authority management agreements Part 4 - Interim Protection Orders 32. Power of Minister to make interim protection orders 33. Terms of interim protection orders 34. Notice of order to landholder 35. Recommendation by Resource Planning and Development Commission 36. Notice to comply 37. Notification to other Ministers 38. Limitation of licences, permits, &c., issued under other Acts 39. -

Amphibromus Neesii

Threatened Species Link www.tas.gov.au SPECIES MANAGEMENT PROFILE Amphibromus neesii southern swampgrass Group: Magnoliophyta (flowering plants), Liliopsida (monocots), Poales, Poaceae Status: Threatened Species Protection Act 1995: rare Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999: Not listed Endemic Found in Tasmania and elsewhere Status: A complete species management profile is not currently available for this species. Check for further information on this page and any relevant Activity Advice. Key Points Important: Is this species in your area? Do you need a permit? Ensure you’ve covered all the issues by checking the Planning Ahead page. Important: Different threatened species may have different requirements. For any activity you are considering, read the Activity Advice pages for background information and important advice about managing around the needs of multiple threatened species. Surveying Key Survey reliability more info To ensure you follow the law - check whether your M Best time to survey survey requires a permit. Always report any new records to the Natural Values Atlas, M Potential time to survey or send the information direct to the Threatened Species Section. Refer to the Activity Advice: Surveying page for background information. M Poor time to survey M Non-survey period Amphibromus neesii Spring Summer Autumn Winter southern swamp grass S S O O N N D D J J F F M M A A M M J J J J A A Flowering of this grass is from October to April (Flora of Victoria). Most herbarium specimens have been collected from December to early March. Mature inflorescences are required for identification. -

Indigenous Plant Guide

Local Indigenous Nurseries city of casey cardinia shire council city of casey cardinia shire council Bushwalk Native Nursery, Cranbourne South 9782 2986 Cardinia Environment Coalition Community Indigenous Nursery 5941 8446 Please contact Cardinia Shire Council on 1300 787 624 or the Chatfield and Curley, Narre Warren City of Casey on 9705 5200 for further information about indigenous (Appointment only) 0414 412 334 vegetation in these areas, or visit their websites at: Friends of Cranbourne Botanic Gardens www.cardinia.vic.gov.au (Grow to order) 9736 2309 Indigenous www.casey.vic.gov.au Kareelah Bush Nursery, Bittern 5983 0240 Kooweerup Trees and Shrubs 5997 1839 This publication is printed on Monza Recycled paper 115gsm with soy based inks. Maryknoll Indigenous Plant Nursery 5942 8427 Monza has a high 55% recycled fibre content, including 30% pre-consumer and Plant 25% post-consumer waste, 45% (fsc) certified pulp. Monza Recycled is sourced Southern Dandenongs Community Nursery, Belgrave 9754 6962 from sustainable plantation wood and is Elemental Chlorine Free (ecf). Upper Beaconsfield Indigenous Nursery 9707 2415 Guide Zoned Vegetation Maps City of Casey Cardinia Shire Council acknowledgements disclaimer Cardinia Shire Council and the City Although precautions have been of Casey acknowledge the invaluable taken to ensure the accuracy of the contributions of Warren Worboys, the information the publishers, authors Cardinia Environment Coalition, all and printers cannot accept responsi- of the community group members bility for any claim, loss, damage or from both councils, and Council liability arising out of the use of the staff from the City of Casey for their information published. technical knowledge and assistance in producing this guide. -

Supplemental Table 1 the Phenology of Chasmogamous (CH) and Cleistogamous (CL) Flower Production by Life History (Annual Or Perennial) and Genus

Supplemental Table 1 The phenology of chasmogamous (CH) and cleistogamous (CL) flower production by life history (annual or perennial) and genus. Phenology is described as sequential (no overlap in the production of CH and CL flowers), overlapping (partial overlap), or simultaneous (complete overlap in production of CH and CL flowers). Flower type initiated first indicates which flower type is produced first within a flowering season. Flower Flower type Genus (Family) phenology initiated first Reference Annuals Amphicarpaea (Fabaceae) Overlapping CL 1-2 Amphicarpum (Poaceae) Overlapping CL 3-4 Andropogon (Poaceae) Overlapping CL 5 Centaurea (Asteraceae) Overlapping CL 6 Ceratocapnos (Fumariaceae) Overlapping CL 7 Collomia (Polemoniaceae) Overlapping CL 8-9 Emex (Polygonaceae) Overlapping CL 10 Impatiens (Balsaminaceae) Overlapping CL 11-16 Lamium (Lamiaceae) Overlapping CL 17 Mimulus (Scrophulariaceae) Overlapping CL 18 Salpiglossis (Solanaceae) Overlapping CL 19 Perennials Ajuga (Lamiaceae) Overlapping CL 20 Amphibromus (Poaceae) Overlapping CL 21 Calathea (Marantaceae) Simultaneous, NA 22 year round Danthonia (Poaceae) Overlapping CL 21; 23-24 Dichanthelium (Poaceae) Sequential CH 25 Microleana (Poaceae) Simultaneous unknown 26 Oxalis (Oxalidaceae) Sequential CH 27-29 Scutellaria (Lamiaceae) Sequential CH 30 Viola (Violaceae) Sequential CH 28; 31-34 LITERATURE CITED 1. Schnee BK, Waller DM. 1986. Reproductive-behavior of Amphicarpaea bracteata (Leguminosae), an amphicarpic annual. Am. J. Bot. 73: 376–86 2. Trapp EJ, Hendrix SD. 1988. Consequences of a mixed reproductive system in the hog peanut, Amphicarpaea bracteata (Fabaceae). Oecologia 75: 285–90 3. Cheplick GP, Quinn JA. 1982. Amphicarpum purshii and the pessimistic strategy in amphicarpic annuals with subterranean fruit. Oecologia 52: 327–32 4. Cheplick GP. 1989. Nutrient availability, dimorphic seed production, and reproductive allocation in the annual grass Amphicarpum purshii. -

South, Tasmania

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Guide to Users Background What is the summary for and where does it come from? This summary has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. It highlights important elements of the biodiversity of the region in two ways: • Listing species which may be significant for management because they are found only in the region, mainly in the region, or they have a conservation status such as endangered or vulnerable. • Comparing the region to other parts of Australia in terms of the composition and distribution of its species, to suggest components of its biodiversity which may be nationally significant. The summary was produced using the Australian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. The list of families covered in ANHAT is shown in Appendix 1. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are are not not included included in the in the summary. • The data used for this summary come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. -

Phylogeny, Morphology and the Role of Hybridization As Driving Force Of

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/707588; this version posted July 18, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Phylogeny, morphology and the role of hybridization as driving force of evolution in 2 grass tribes Aveneae and Poeae (Poaceae) 3 4 Natalia Tkach,1 Julia Schneider,1 Elke Döring,1 Alexandra Wölk,1 Anne Hochbach,1 Jana 5 Nissen,1 Grit Winterfeld,1 Solveig Meyer,1 Jennifer Gabriel,1,2 Matthias H. Hoffmann3 & 6 Martin Röser1 7 8 1 Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, Institute of Biology, Geobotany and Botanical 9 Garden, Dept. of Systematic Botany, Neuwerk 21, 06108 Halle, Germany 10 2 Present address: German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv), Deutscher 11 Platz 5e, 04103 Leipzig, Germany 12 3 Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, Institute of Biology, Geobotany and Botanical 13 Garden, Am Kirchtor 3, 06108 Halle, Germany 14 15 Addresses for correspondence: Martin Röser, [email protected]; Natalia 16 Tkach, [email protected] 17 18 ABSTRACT 19 To investigate the evolutionary diversification and morphological evolution of grass 20 supertribe Poodae (subfam. Pooideae, Poaceae) we conducted a comprehensive molecular 21 phylogenetic analysis including representatives from most of their accepted genera. We 22 focused on generating a DNA sequence dataset of plastid matK gene–3'trnK exon and trnL– 23 trnF regions and nuclear ribosomal ITS1–5.8S gene–ITS2 and ETS that was taxonomically 24 overlapping as completely as possible (altogether 257 species). -

PAS062 Nelson River Flora and Fauna Habitat Assessment

Nelson River – Shree Minerals Mine & Infrastructure Proposal Flora and Fauna Habitat Assessment 22 nd March 2011 For Shree Minerals Andrew North [email protected] Philip Barker [email protected] 163 Campbell Street Hobart TAS 7000 Telephone 03. 6231 9788 Facsimile 03. 6231 9877 Flora and Fauna Habitat Assessment – Nelson River- Shree Minerals Mine Proposal SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS Shree Minerals has commissioned Pitt and Sherry to develop a Development Proposal and Environmental Management Plan (DPEMP) for the proposed Nelson Bay River Mine and associated infrastructure. The proposed Nelson Bay River site is located partly within the Arthur Pieman Protected area and partly on State Forest approximately 4 km inland from Couta Rocks and Nelson Bay on the west coast of Tasmania. The closest township is Arthur River, adjacent to the mouth of the Arthur River. Pitt and Sherry has engaged North Barker Ecosystem Services to undertake a flora and fauna habitat assessment to assess the natural values of the deep pit/ open cut mine and associated infrastructure sites including waste dump, tailings dam, processing plant and direct shipping pit within the study area. In addition the balance of the exploration lease was also surveyed to allow for infrastructure to be moved at a later date without requiring additional survey. This report presents the findings of the vegetation and habitat assessment. Vegetation Communities None of the vegetation communities within the mining lease are threatened. The native vegetation communities -

Art Installation, Ida Bay Flora and Fauna Habitat Assessment

Transformer – Art Installation, Ida Bay Flora and Fauna Habitat Assessment, Including Collision Risk 1st December 2020 For DarkLab, MONA Andrew North [email protected] Philip Barker [email protected] 163 Campbell Street Hobart TAS 7000 Telephone 03. 6231 9788 Facsimile 03. 6231 9877 Transformer, Ida Bay Flora and Fauna Habitat Assessment SUMMARY The proponent DarkLab, of the MONA (Museum of Old and New Art) group, are in the planning phase for a proposed permanent art installation called Transformer at Ida Bay. North Barker Ecosystem Services (NBES) have been engaged to undertake a flora and fauna habitat assessment of the project area, including a collision risk assessment for the swift parrot. Vegetation Four native TASVEG vegetation units have been recorded within the project area, none of which are threatened under the EPBCA or the NCA: - DOB – Eucalyptus obliqua dry forest - MBS – buttongrass moorland with emergent shrubs - SHW – wet heathland - SMR – Melaleuca squarrosa scrub Threatened Flora The footprint does not overlap with any known occurrences of threatened flora and it is not expected to have any unanticipated impacts in relation to undocumented occurrences. Weeds The survey area was found to be relatively free of serious weeds. Only two declared weeds were recorded in small amounts. No symptomatic evidence of Phytophthora cinnamomi was observed within the site, but the wet heath community is particularly susceptible to its impacts. Threatened Fauna The property and the broader Ida Bay contains potential foraging and nesting habitat for the swift parrot, including habitat patches and elements (such as hollow-bearing trees) around the proposed footprint. -

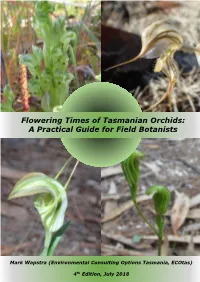

Flowering Times of Tasmanian Orchids: a Practical Guide for Field Botanists

Flowering Times of Tasmanian Orchids: A Practical Guide for Field Botanists Mark Wapstra (Environmental Consulting Options Tasmania, ECOtas) 4th Edition, July 2018 Flowering Times of Tasmanian Orchids: A Practical Guide for Field Botanists 4th Edition (July 2018) MARK WAPSTRA Flowering Times of Tasmanian Orchids: A Practical Guide for Field Botanists FOREWORD TO FIRST EDITION (2008) This document fills a significant gap in the Tasmanian orchid literature. Given the inherent difficulties in locating and surveying orchids in their natural habitat, an accurate guide to their flowering times will be an invaluable tool to field botanists, consultants and orchid enthusiasts alike. Flowering Times of Tasmanian Orchids: A Practical Guide for Field Botanists has been developed by Tasmania’s leading orchid experts, drawing collectively on many decades of field experience. The result is the most comprehensive State reference on orchid flowering available. By virtue of its ease of use, accessibility and identification of accurate windows for locating our often-cryptic orchids, it will actually assist in conservation by enabling land managers and consultants to more easily comply with the survey requirements of a range of land-use planning processes. The use of this guide will enhance efforts to locate new populations and increase our understanding of the distribution of orchid species. The Threatened Species Section commends this guide and strongly recommends its use as a reference whenever surveys for orchids are undertaken. Matthew Larcombe Project Officer (Threatened Orchid and Euphrasia) Threatened Species Section, Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water & Environment March 2008 DOCUMENT AVAILABILITY This document is freely available as a PDF file downloadable from the following websites: www.fpa.tas.gov.au; www.dpipwe.tas.gov.au; www.ecotas.com.au.