Interior Chumash

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate Adaptation Report

Caltrans CCAP: District Interviews Summary October 2019 San Joaquin Council of Governments Climate Adaptation & Resiliency Study Climate Adaptation Report APRIL 2, 2020 1 Climate Adaptation Report March 2020 Contents Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 5 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 7 Vulnerability Assessment: Key Findings ...................................................................................................... 10 Gaps and Recommendations ...................................................................................................................... 16 Integrating Transportation Resilience into the Regional Transportation Plan (RTP).............................. 17 Next Steps ................................................................................................................................................... 18 Appendix A: Detailed Vulnerability Assessment Report ............................................................................. 20 Introduction -

Center Comments to the California Department of Fish and Game

July 24, 2006 Ryan Broderick, Director California Department of Fish and Game 1416 Ninth Street, 12th Floor Sacramento, CA 95814 RE: Improving efficiency of California’s fish hatchery system Dear Director Broderick: On behalf of the Pacific Rivers Council and Center for Biological Diversity, we are writing to express our concerns about the state’s fish hatchery and stocking system and to recommend needed changes that will ensure that the system does not negatively impact California’s native biological diversity. This letter is an update to our letter of August 31, 2005. With this letter, we are enclosing many of the scientific studies we relied on in developing this letter. Fish hatcheries and the stocking of fish into lakes and streams cause numerous measurable, significant environmental effects on California ecosystems. Based on these impacts, numerous policy changes are needed to ensure that the Department of Fish and Game’s (“DFG”) operation of the state’s hatchery and stocking program do not adversely affect California’s environment. Further, as currently operated, the state’s hatchery and stocking program do not comply with the California Environmental Quality Act, Administrative Procedures Act, California Endangered Species Act, and federal Endangered Species Act. The impacts to California’s environment, and needed policy changes to bring the state’s hatchery and stocking program into compliance with applicable state and federal laws, are described below. I. FISH STOCKING NEGATIVELY IMPACTS CALIFORNIA’S NATIVE SALMONIDS, INCLUDING THREATENED AND ENDANGERED SPECIES Introduced salmonids negatively impact native salmonids in a variety of ways. Moyle, et. al. (1996) notes that “Introduction of non-native fish species has also been the single biggest factor associated with fish declines in the Sierra Nevada.” Moyle also notes that introduced species are contributing to the decline of 18 species of native Sierra Nevada fish species, and are a major factor in the decline of eight of those species. -

Developing Ecological Site and State-And-Transition Models For

Developing Ecological Site and State-and- Transition Models for Grazed Riparian 1 Pastures at Tejon Ranch, California Felix P. Ratcliff,2 James Bartolome,2 Michele Hammond,2 Sheri 2 3 Spiegal, and Michael White Abstract Ecological site descriptions and associated state-and-transition models are useful tools for understanding the variable effects of management and environment on range resources. Models for woody riparian sites have yet to be fully developed. At Tejon Ranch, in the southern San Joaquin Valley of California, we are using ecological site theory to investigate the role of two managed ungulate populations, cattle and feral pigs, on riparian woodland communities. Responses in plant species composition, woody plant recruitment, and vegetation structure will be measured by comparing cattle and feral pig management treatments among and between areas with similar abiotic conditions (ecological sites). Results from the second year of this project highlight the spatial variability of riparian woodland vegetation communities as well as temporally and spatially variable abundances of cattle and feral pigs. Development of riparian ecological site descriptions and state-and-transition models provide both a generalizable framework for evaluating management alternatives in riparian areas, and also specific direction for managing cattle and feral pigs. Key words: cattle, ecological site descriptions feral pigs, riparian area management, state-and transition models Introduction Ecological site concepts and state-and-transition models have been widely developed to model spatial and temporal vegetation dynamics in arid rangelands. An ‘Ecological Site’ as defined by the Natural Resources Conservation Service is “a distinctive kind of land with specific physical characteristics that differs from other kinds of land in its ability to produce a distinctive kind and amount of vegetation, and in its ability to respond to management actions and natural disturbances” (Bestelmeyer and Brown 2010, Caudle and others 2013). -

Minutes of Board Meeting November 2010

STATE OF CALIFORNIA-NATURAL RESOURCES AGENCY ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER, Governor DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME WILDLIFE CONSERVATION BOARD TH 1807 13 STREET, SUITE 103 SACRAMENTO, CALIFORNIA 95811 (916) 445-8448 FAX (916) 323-0280 www.wcb.ca.gov State of California Natural Resources Agency Department of Fish and Game WILDLIFE CONSERVATION BOARD Minutes November 18, 2010 ITEM NO. PAGE NO. 1. Roll Call 1 2. Funding Status — Informational 3 3. Special Project Planning Account — Informational 7 4. Proposed Consent Calendar (Items 4—17) 8 *5. Approval of Minutes — August 26, 2010 8 *6. Recovery of Funds 9 *7. Fund Shift 11 Various Counties *8. Hamilton City Flood Damage Reduction and Ecosystem Restoration 13 Glenn County *9. Loch Lomond Vernal Pool Ecological Reserve Exchange 18 Lake County *10. Swiss Ranch, Expansion 3 20 Calaveras County *11. Eticuera Creek Watershed Habitat Restoration 23 Napa County *12. Napa-Sonoma Marshes Wildlife Area,, American Canyon 26 Napa County *13. Insectaries for Pollinators and Farm Biodiversity 28 Sonoma County *14. Goleta Slough Ecological Reserve Restoration, 31 Augmentation and Change of Scope Merced County *15. James San Jacinto Mountains Reserve Renovation 35 Riverside County *16. Peninsular Bighorn Sheep 37 Riverside County * Proposed Consent Calendar i ITEM NO. PAGE NO. *17. East Elliott and Otay Mesa Regions (Sunroad) 40 San Diego County 18. Cow Creek Conservation Area, Expansion 2 43 Shasta County 19. Red Bank Creek 46 Tehama County 20. Heart K Ranch 49 Plumas County 21. Upper Butte Basin Wildlife Area, Expansion 6 53 Butte County 22. Lower Yuba River, Excelsior, Phase I 56 Nevada and Yuba Counties 23. -

State of California

Upper Piru Creek Wild Trout Management Plan 2012-2017 State of California Department of Fish and Game Heritage and Wild Trout Program South Coast Region Prepared by Roger Bloom, Stephanie Mehalick, and Chris McKibbin 2012 Table of contents Executive summary .................................................................................. 3 Resource status ........................................................................................ 3 Area description ...................................................................................................... 3 Land ownership/administration ............................................................................... 4 Public access .......................................................................................................... 4 Designations ........................................................................................................... 4 Area maps............................................................................................................... 5 Figure 1. Vicinity map of upper Piru Creek watershed ............................................ 5 Figure 2. Map of upper Piru Creek Heritage and Wild Trout-designated reach....... 6 Fishery description.................................................................................................. 6 Figure 3. Photograph of USGS gaging station near confluence of Piru and Buck creeks ..................................................................................................................... 7 -

Fish Commission Biennial Report

California. Dept. of Fish and Gair.e. Biennial Report 1910-1912. C . /:- ...BlHiNlflt- REPORl OF CHE 111: ;'t'(ifT;^ EIBMxflND GAME COMMISSIQ|^^ - / :310~1912 STATE OF :ClVL!FORNlA California. Dept. of Fish and Game. Biennial Report 1910-1912. (bound volume) C.2 DATE DUE J California. Dept. of Fish and I Game. Biennial Report 1910-1912. (bound j volume) California Resources Agency Library 1416 9th Street, Room 117 Sacramento, California 95814 CALIFORNIA RESGLIRCES AGEMCY LlBRAtil Resources ^%j\id'm^, Room 117 1416 - 9tli Street Sacramento, California 95814 STATE OF CALIFORNIA Fish and Game Commission TWENTY-SECOND BIENNIAL REPORT For the Years 1910-1912 Friend Wm. Richardson, Superintendent of State Printing sacramento, california 1913 CONTENTS. PART ONE. Page. Personnel and Organization of Board 7 Peace Officers and Forest Service Cooperation 8 Salaried, or Regular Officers 9 Special Deputies Program and Work 9 What the Commission Has Done in Tv/o Years 12 Recommendations 14 Acknowledgments 15 Game Conditions in California 17 Operation of State Game Farm 26 Propagation and Distribution of Fish 1910-1911 30 Trout Egg Collection and Distribution 1910-1911 31 Report of Superintendent of Hatcheries 32 PART TWO. Administrative Districts 47 Roster of Employees 48 Inventory 51 Revenues and Expenditures 52 Seizures and Prosecutions Folder Hunting Licenses Issued 56 Commercial Fishing Licenses Issued 58 Lion Bounties Paid 59 Game Bird Distribution 60 Fish Distribution, Season 1911 63- Fish Distribution, Season 1912 64 LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL. San Francisco, Cal., December 31, 1912. Bon. iEIiRAM W. Johnson, Governor, State of California, Sacramento, Cal. Sir: In accordance with law, we submit for your consideration a statement of the transactions and disbursements of the Board for the biennial term July 1, 1910, to June 30, 1912. -

Initial Study Pumpkin Center 3R Rehabilitation

Pumpkin Center 3R Rehabilitation State Route 119 in Pumpkin Center in Kern County 06-KER-119-PM 28.2/31.3 Project ID 0616000222 Initial Study with Proposed Mitigated Negative Declaration Volume 1 of 2 Prepared by the State of California Department of Transportation June 2020 General Information About This Document What’s in this document: The California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) has prepared this Initial Study, which examines the potential environmental impacts of alternatives being considered for the proposed project in Kern County in California. The document explains why the project is being proposed, the alternatives being considered for the project, the existing environment that could be affected by the project, potential impacts of each of the alternatives, and proposed avoidance, minimization, and/or mitigation measures. What you should do: · Please read the document. Additional copies of the document and the related technical studies are available for review at the Caltrans district office at 1352 West Olive Avenue, Fresno, California, 93728, weekdays from 8:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m., and the California Highway Patrol Office, 9855 Compagnoni Street, Bakersfield, California, 93313, weekdays from 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. To obtain a hard copy of the document, please contact Som Phongsavanh at 559-445-6447. The document can also be accessed electronically at the following website: http://www.dot.ca.gov/caltrans-near-me/district-6 · Tell us what you think. Send your written comments to Caltrans by the deadline. Submit comments via U.S. mail to: Som Phongsavanh, Central Region Environmental, California Department of Transportation, 855 M Street, Suite 200, Fresno, California, 93721. -

Gazetteer of Surface Waters of California

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTI8 SMITH, DIEECTOE WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 296 GAZETTEER OF SURFACE WATERS OF CALIFORNIA PART II. SAN JOAQUIN RIVER BASIN PREPARED UNDER THE DIRECTION OP JOHN C. HOYT BY B. D. WOOD In cooperation with the State Water Commission and the Conservation Commission of the State of California WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1912 NOTE. A complete list of the gaging stations maintained in the San Joaquin River basin from 1888 to July 1, 1912, is presented on pages 100-102. 2 GAZETTEER OF SURFACE WATERS IN SAN JOAQUIN RIYER BASIN, CALIFORNIA. By B. D. WOOD. INTRODUCTION. This gazetteer is the second of a series of reports on the* surf ace waters of California prepared by the United States Geological Survey under cooperative agreement with the State of California as repre sented by the State Conservation Commission, George C. Pardee, chairman; Francis Cuttle; and J. P. Baumgartner, and by the State Water Commission, Hiram W. Johnson, governor; Charles D. Marx, chairman; S. C. Graham; Harold T. Powers; and W. F. McClure. Louis R. Glavis is secretary of both commissions. The reports are to be published as Water-Supply Papers 295 to 300 and will bear the fol lowing titles: 295. Gazetteer of surface waters of California, Part I, Sacramento River basin. 296. Gazetteer of surface waters of California, Part II, San Joaquin River basin. 297. Gazetteer of surface waters of California, Part III, Great Basin and Pacific coast streams. 298. Water resources of California, Part I, Stream measurements in the Sacramento River basin. -

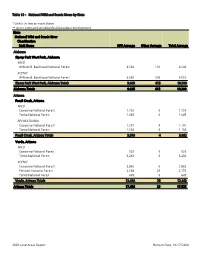

Land Areas Report Refresh Date: 10/17/2020 Table 13 - National Wild and Scenic Rivers by State

Table 13 - National Wild and Scenic Rivers by State * Unit is in two or more States ** Acres estimated pending final boundary development State National Wild and Scenic River Classification Unit Name NFS Acreage Other Acreage Total Acreage Alabama Sipsey Fork West Fork, Alabama WILD William B. Bankhead National Forest 6,134 110 6,244 SCENIC William B. Bankhead National Forest 3,550 505 4,055 Sipsey Fork West Fork, Alabama Totals 9,685 615 10,300 Alabama Totals 9,685 615 10,300 Arizona Fossil Creek, Arizona WILD Coconino National Forest 1,720 0 1,720 Tonto National Forest 1,085 0 1,085 RECREATIONAL Coconino National Forest 1,137 4 1,141 Tonto National Forest 1,136 0 1,136 Fossil Creek, Arizona Totals 5,078 4 5,082 Verde, Arizona WILD Coconino National Forest 525 0 525 Tonto National Forest 6,234 0 6,234 SCENIC Coconino National Forest 2,862 0 2,862 Prescott National Forest 2,148 25 2,173 Tonto National Forest 649 0 649 Verde, Arizona Totals 12,418 25 12,443 Arizona Totals 17,496 29 17,525 2020 Land Areas Report Refresh Date: 10/17/2020 Table 13 - National Wild and Scenic Rivers by State * Unit is in two or more States ** Acres estimated pending final boundary development State National Wild and Scenic River Classification Unit Name NFS Acreage Other Acreage Total Acreage Arkansas Big Piney Creek, Arkansas SCENIC Ozark National Forest 6,448 781 7,229 Big Piney Creek, Arkansas Totals 6,448 781 7,229 Buffalo, Arkansas WILD Ozark National Forest 2,871 0 2,871 SCENIC Ozark National Forest 1,915 0 1,915 Buffalo, Arkansas Totals 4,785 0 4,786 -

List of Fish and Game Commission Designated Wild Trout Waters

The following waters are designated by the Commission as "wild trout waters": 1. American River, North Fork, from Palisade Creek downstream to Iowa Hill Bridge (Placer County). 2. Carson River, East Fork, upstream from confluence with Wolf Creek excluding tributaries (Alpine County). 3. Clavey River, upstream from confluence with Tuolumne River excluding tributaries (Tuolumne County). 4. Fall River, from Pit No. 1 powerhouse intake upstream to origin at Thousand Springs including Spring Creek, but excluding all other tributaries (Shasta County). 5. Feather River, Middle Fork, from Oroville Reservoir upstream to Sloat vehicle bridge, excluding tributaries (Butte and Plumas counties). 6. Hat Creek, from Lake Britton upstream to Hat No. 2 powerhouse (Shasta County). 7. Hot Creek, from Hot Springs upstream to west property line of Hot Creek Ranch (Mono County). 8. Kings River, from Pine Flat Lake upstream to confluence with South and Middle forks excluding tributaries (Fresno County). 9. Kings River, South Fork, from confluence with Middle Fork upstream to western boundary of Kings Canyon National Park excluding tributaries (Fresno County). 10. Merced River, South Fork, from confluence with mainstem Merced River upstream to western boundary of Yosemite National Park excluding tributaries (Mariposa County). 11. Nelson Creek, upstream from confluence with Middle Fork Feather River excluding tributaries (Plumas County). 12. Owens River, from Five Bridges crossing upstream to Pleasant Valley Dam excluding tributaries (Inyo County). 13. Rubicon River, from confluence with Middle Fork American River upstream to Hell Hole Dam excluding tributaries (Placer County). 14. Yellow Creek, from Big Springs downstream to confluence with the North Fork of the Feather River (Plumas County). -

Draft SEIR Chapter 2 Program Description

1 Chapter 2 2 PROGRAM DESCRIPTION 3 2.1 Introduction 4 2.1.1 Program Purpose 5 The purpose of the Proposed Program is to establish and implement a permitting program 6 for suction dredging activities consistent with the requirements of Fish and Game Code 7 section 5653 et seq. and the December 2006 Court Order. 8 2.1.2 Program Objectives 9 The objectives of the Proposed Program are as follows: 10 Comply with the December 2006 Court Order; 11 Promulgate amendments to CDFG’s previous regulations as necessary to 12 effectively implement Fish and Game Code sections 5653 and 5653.9 and other 13 applicable legal authorities to ensure that suction dredge mining will not be 14 deleterious to fish; 15 Develop a program that is implementable within the existing fee structure 16 established by statute for the CDFG’s suction dredge permitting program, as well 17 as the existing fee structure established by the CDFG pursuant to Fish and Game 18 Code section 1600 et seq.; 19 Fulfill CDFG’s mission to manage California's diverse fish, wildlife, and plant 20 resources, and the habitats upon which they depend, for their ecological values 21 and for their use and enjoyment by the public; 22 Ensure that the development of the regulations considers economic costs, 23 practical considerations for implementation, and technological capabilities 24 existing at the time of implementation; and 25 Fulfill the CDFG’s obligation to conserve, protect, and manage fish, wildlife, 26 native plants, and habitats necessary for biologically sustainable populations of 27 those species and as a trustee agency for fish and wildlife resources pursuant to 28 Fish and Game Code section 1802. -

National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet

NPSForm10-900-a OMB Approval No. 1024-0018 (8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet Section number Page SUPPLEMENTARY LISTING RECORD NRIS Reference Number: 99001263 Date Listed: 10/20/99 Tehachapi Railroad Depot Kern CA Property Name County State N/A Multiple Name This property is listed in the National Register of Historic Places in accordance with the attached nomination documentation subject to the following exceptions, exclusions, or amendments, notwithstanding the National Park Service certification included in the nomination documentation. / Signature^of Me Keeper Date of Action Amended Items in Nomination: Significance: The nomination incorrectly refers to the nearby Tehachapi "Loop" as a National Historic Landmark [8.1]. This information was confirmed with the California SHPO. DISTRIBUTION: National Register property file Nominating Authority (without nomination attachment) NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM L. This form is for use in nominating or requesting c^ete: individual properties and districts. See instructions in the National Register of Historic Places Registral Register Bulletin 16A) . Complete each item by marking Tl x""™ii appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items.