Pandemic Disease in the Medieval World Rethinking the Black Death

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plague Manual for Investigation

Plague Summary Plague is a flea-transmitted bacterial infection of rodents caused by Yersinia pestis. Fleas incidentally transmit the infection to humans and other susceptible mammalian hosts. Humans may also contract the disease from direct contact with an infected animal. The most common clinical form is acute regional lymphadenitis, called bubonic plague. Less common clinical forms include septicemic, pneumonic, and meningeal plague. Pneumonic plague can be spread from person to person via airborne transmission, potentially leading to epidemics of primary pneumonic plague. Plague is immediately reportable to the New Mexico Department of Health. Plague is treatable with antibiotics, but has a high fatality rate with inadequate or delayed treatment. Plague preventive measures include: isolation of pneumonic plague patients; prophylactic treatment of pneumonic case contacts; avoiding contact with rodents and their fleas; reducing rodent harborage around the home; using flea control on pets; and, preventing pets from hunting. Agent Plague is caused by Yersinia pestis, a gram-negative, bi-polar staining, non-motile, non-spore forming coccobacillus. Transmission Reservoir: Wild rodents (especially ground squirrels) are the natural vertebrate reservoir of plague. Lagomorphs (rabbits and hares), wild carnivores, and domestic cats may also be a source of infection to humans. Vector: In New Mexico, the rock squirrel flea, Oropsylla montana, is the most important vector of plague for humans. Many more flea species are involved in the transmission of sylvatic (wildlife) plague. Mode of Transmission: Most humans acquire plague through the bites of infected fleas. Fleas can be carried into the home by pet dogs and cats, and may be abundant in woodpiles or burrows where peridomestic rodents such as rock squirrels (Spermophilus variegatus) have succumbed to plague infection. -

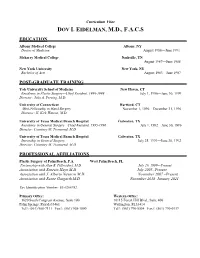

Dov I. Eidelman, Md, Facs

Curriculum Vitae DOV I. EIDELMAN, M.D., F.A.C.S EDUCATION Albany Medical College Albany, NY Doctor of Medicine August 1988—June 1991 Meharry Medical College Nashville, TN August 1987—June 1988 New York University New York, NY Bachelor of Arts August 1983—June 1987 POST-GRADUATE TRAINING Yale University School of Medicine New Haven, CT Residency in Plastic Surgery—Chief Resident, 1998-1999 July 1, 1996—June 30, 1999 Director: John A. Persing, M.D. University of Connecticut Hartford, CT Mini-Fellowship in Hand Surgery November 1, 1996—December 31, 1996 Director: H. Kirk Watson, M.D. University of Texas Medical Branch Hospital Galveston, TX Residency in General Surgery—Chief Resident, 1995-1996 July 1, 1992—June 30, 1996 Director: Courtney M. Townsend, M.D University of Texas Medical Branch Hospital Galveston, TX Internship in General Surgery July 25, 1991—June 30, 1992 Director: Courtney M. Townsend, M.D PROFESSIONAL AFFILIATIONS Plastic Surgery of Palm Beach, P.A. West Palm Beach, FL Partnership with Alan B. Pillersdorf, M.D. July 20, 1999—Present Association with Ernesto Hayn M.D. July 2005- Present Association with J. Alberto Navarro M.D. November 2007 –Present Association with Renee Gasgarth M.D. November 2018–January 2021 Tax Identification Number: 65-0208782 Primary Office: Western Office: 1620 South Congress Avenue, Suite 100 10115 Forest Hill Blvd., Suite 400 Palm Springs, Florida33461 Wellington, FL33414 Tel#: (561) 968-7111 Fax#: (561) 968-1800 Tel#: (561) 790-5554 Fax#: (561) 790-0139 BOARD CERTIFICATION The American Board of Plastic Surgery Board Certified in Plastic Surgery –September 9, 2000 Re-Certified: December 1, 2010 Certification Number: 5962 MEDICAL LICENSURE DEA# BE6316132 (Exp. -

Archaeological Surveys in Lower Sindh: Preliminary Results of the 2009 Season

Journal of Asian Civilizations -1- Archaeological Surveys in Lower Sindh: Preliminary Results of the 2009 Season Paolo Biagi ABSTRACT In January-February 2009 archaeological surveys were conducted in three different regions of Lower Sindh, from Ranikot, in the north, to the Makli Hills, in the south. They resulted in the discovery of many sites and flint spots within a territory the archaeology of which was previously poorly known. This paper is aimed at the description of these finds, their cultural attribution and, whenever possible, absolute chronology. Particular attention has been paid to the radiocarbon chronology of the sites located on the rocky outcrops that rise from the alluvial plain of the Indus delta, a few of which indicate that seafaring along the northern shores of the Arabian Sea was already active at least since the very beginning of the seventh millennium uncal BP. 1. PREFACE This paper is a preliminary report of the surveys carried out in January and February 2009 in Lower Sindh, between Ranikot, in the north, and the Makli Hills, in the south. The scope of the surveys, which were part of a joint venture by Ca’ Foscari University, Venice (I) and Sindh University, Jamshoro (PK), was to discover new archaeological sites in a territory insufficiently explored, and define their cultural attribution and absolute chronology by radiocarbon dating. Although some parts of the above region had already been surveyed by other authors (see, for instance, MAJUMDAR, 1934; COUSENS, 1998; FRANKE-VOGT, 1999; FLAM, 2006), our attention focused mainly on territories never accurately investigated before. The surveys were conducted by systematic walking in the three main, well- defined areas described in the following chapters (fig. -

The Black Death and Early Modern Witch-Hunts

Plague and Persecution: The Black Death and Early Modern Witch-Hunts History 480: Major Seminar II Helen Christian Professor Laura Beers April 27, 2011 2 Abstract The century or so from approximately 1550 to 1650 is a period during which witch-hunts reached unprecedented frequency and intensity. The circumstances that fomented the witch- hunts—persistent warfare, religious conflict, and harvest failures—had occurred before, but witch-hunts had never been so ubiquitous or severe. This paper argues that the intensity of the Early Modern witch-hunts can be traced back to the plague of 1348, and argues that the plague was a factor in three ways. First, the plague’s devastation and the particularly unpleasant nature of the disease traumatized the European psyche, meaning that any potential recurrence of plague was a motivation to search for scapegoats. Second, the population depletion set off a chain of events that destabilized Europe. Finally, witch-hunters looked to the example set by the interrogators of suspected “plague-spreaders” and copied many of their interrogation and trial procedures. 3 Table of Contents Introduction 4 Historiography 7 The Plague and “Plague-Spreaders” 9 The Otherwise Calamitous Fourteenth Century 15 The Reformation 18 The Witch-Hunting Craze 22 The Plague in the Early Modern Period 25 Medieval Persecution in the Witch-Hunts 29 Conclusion 35 4 Introduction The Black Death of 1348 had tremendous political, social, economic, and psychological impact on Europe and the trajectory of European history. By various estimates, the plague wiped out between one-third and one-half of the population in only a few years. -

Ticino on the Move

Tales from Switzerland's Sunny South Ticino on theMuch has changed move since 1882, when the first railway tunnel was cut through the Gotthard and the Ceneri line began operating. Mendrisio’sTHE LIGHT Processions OF TRADITION are a moving experience. CrystalsTREASURE in the AMIDST Bedretto THE Valley. ROCKS ChestnutsA PRICKLY are AMBASSADOR a fruit for all seasons. EasyRide: Travel with ultimate freedom. Just check in and go. New on SBB Mobile. Further information at sbb.ch/en/easyride. EDITORIAL 3 A lakeside view: Angelo Trotta at the Monte Bar, overlooking Lugano. WHAT'S NEW Dear reader, A unifying path. Sopraceneri and So oceneri: The stories you will read as you look through this magazine are scented with the air of Ticino. we o en hear playful things They include portraits of men and women who have strong ties with the local area in the about this north-south di- truest sense: a collective and cultural asset to be safeguarded and protected. Ticino boasts vide. From this year, Ticino a local rural alpine tradition that is kept alive thanks to the hard work of numerous young will be unified by the Via del people. Today, our mountain pastures, dairies, wineries and chestnut woods have also been Ceneri themed path. restored to life thanks to tourism. 200 years old but The stories of Lara, Carlo and Doris give off a scent of local produce: of hay, fresh not feeling it. milk, cheese and roast chestnuts, one of the great symbols of Ticino. This odour was also Vincenzo Vela was born dear to the writer Plinio Martini, the author of Il fondo del sacco, who used these words to 200 years ago. -

The Justinianic Plague's Origins and Consequences

The Justinianic plague’s origins and consequences Georgiana Bianca Constantin1, Ionuţ Căluian2 1Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, Dunarea de Jos University Galati, Romania 2Valahia University Targoviste, Romania Corresponding author: Georgiana Bianca Constantin Abstract The bubonic plague is an extremely old disease (apparentely from the late Neolitic era). The so-called “Justinianic plague”of the sixth century was the first well-attested outbreak of bubonic plague in the history of the Mediterranean world. It was thought that the Justinianic Plague, along with barbarian invasions, contributed directly to the so-called “Fall of the Roman Empire.” Keywords: plague, pandemics, history Introduction The bubonic plague is an extremely old disease, and scientists have detected the DNA of the pathogen that causes it—the bacterium Yersinia pestis—in the remains of late Neolithic era [1]. The limited details in historical texts have led scholars to question whether the causative agent of Justinianic Plague was truly Yersinia pestis, a debate that was only resolved recently through ancient DNA analysis [2-4]. Three major plague epidemics have been recorded worldwide so far: the “Justinian” plague in the 6th century, the “Black Death” in the 14th century and the recent 20th century pandemic [5]. The plague first hit cities in the southeastern Mediterranean, and moved swiftly through the Levant to the imperial capital of Constantinople. It seems that the plague arrived in Constantinople in 542 CE and the outbreak continued to sweep throughout the Mediterranean world for another 225 years, finally disappearing in 750 CE [1,6]. It is difficult to approximate the overall mortality rate due to the 542 plague, because of the lack of demographical data. -

Norovirus Background

DOH 420-180 Norovirus Background Clinical Syndrome of Norovirus Symptoms Norovirus can cause acute gastroenteritis in persons of all ages. Symptoms include acute onset non- bloody diarrhea, vomiting, nausea, and abdominal pain, sometimes accompanied by low-grade fever, body aches, and headache.2,3 Some individuals may only experience vomiting or diarrhea. Dehydration is a concerning secondary outcome.2 Symptoms typically resolve without treatment in 1-3 days in healthy individuals. Illness can last 4-6 days and may manifest more severely in young children elderly persons, and hospitalized patients.2,3 Diarrhea is more common in adults, while vomiting is more common among children.4 Up to 30% of norovirus infections are asymptomatic.2 Incubation The incubation period for norovirus is 12-48 hours.2 Transmission The only known reservoir for norovirus is humans. Transmission occurs by three routes: person-to- person, foodborne, or waterborne.2 Individuals can be infected by coming into contact with infected individuals (through the fecal-oral route or by ingestion of aerosolized vomitus or feces), contaminated foods or water, or contaminated surfaces or fomites.1,2 Viral shedding occurs for 4 weeks on average following infection, with peak viral shedding occurring 2-5 days after infection.2 Norovirus is extremely contagious, with an estimated infectious dose as low as 18 viral particles, indicating that even small amounts of feces can contain billions of infectious doses.2 The period of communicability includes the acute phase of illness up through 48 hours after conclusion of diarrhea. Treatment Treatment of norovirus gastroenteritis primarily includes oral rehydration through water, juice, or ice chips. -

The Epidemic of Justinian (Ad 542): a Prelude to the Middle Ages 1. Introduction

Acta Theologica Supplementum 7 2005 THE EPIDEMIC OF JUSTINIAN (AD 542): A PRELUDE TO THE MIDDLE AGES ABSTRACT The epidemic that struck Constantinople and the surrounding countries during the reign of Justinian in the middle of the 6th century, was the first documented pan- demic in history. It marked the beginning of plague as a nosological problem that would afflict the world until the 21st century. The symptoms of the disease, as de- scribed by various contemporary writers (especially the historian and confidant of the emperor, Procopius, and the two church historians, John of Ephesus and Euagrius), are discussed. There is little doubt that the disease was the plague. The most com- mon form in which it manifested was bubonic plague, which is spread by infected fleas and is not directly contagious from patient to patient. There is also evidence of septicaemic plague and possibly even pneumonic plague. The disastrous effects of the plague were described vividly by contemporary writers. A major problem was to find ways to dispose of infected corpses. It is estimated that about one third of the popu- lation died — a figure comparable to the death rate during the Black Death in the Middle Ages. Famine and inflation, the depopulation of the countryside, and a cri- tical manpower shortage in the army were further effects which all contributed to bringing to a premature end Justinian’s attempt to restore the grandeur of the Roman empire, and precipitating the advent of the Middle Ages. 1. INTRODUCTION The epidemic which devastated Constantinople in the 6th century during the reign of Justinian formed part of the first genuine pandemic in history to be documented. -

A Century of Turmoil

356-361-0314s4 10/11/02 4:01 PM Page 356 TERMS & NAMES 4 •Avignon A Century • Great Schism • John Wycliffe • Jan Hus • bubonic plague of Turmoil • Hundred Years’ War MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW • Joan of Arc During the 1300s, Europe was torn apart Events of the 1300s led to a change in by religious strife, the bubonic plague, attitudes toward religion and the state, and the Hundred Years’ War. a change reflected in modern attitudes. SETTING THE STAGE At the turn of the century between the 1200s and 1300s, church and state seemed in good shape, but trouble was brewing. The Church seemed to be thriving. Ideals of fuller political representation seemed to be developing in France and England. However, the 1300s were filled with disasters, both natural and manmade. By the end of the century, the medieval way of life was beginning to disappear. A Church Divided At the beginning of the 1300s, the papacy seemed in some ways still strong. Soon, however, both pope and Church were in desperate trouble. Pope and King Collide The pope in 1300 was an able but stubborn Italian. Pope Boniface VIII attempted to enforce papal authority on kings as previous popes had. When King Philip IV of France asserted his authority over French bishops, Boniface responded with a papal bull (an official document issued by the pope). It stated, “We declare, state, and define that subjection to the Roman Vocabulary Pontiff is absolutely necessary for the salvation of every Pontiff: the pope. human creature.” In short, kings must always obey popes. -

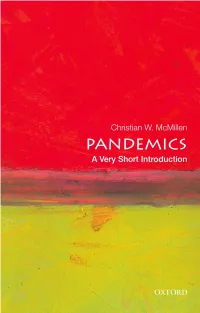

Pandemics: a Very Short Introduction VERY SHORT INTRODUCTIONS Are for Anyone Wanting a Stimulating and Accessible Way Into a New Subject

Pandemics: A Very Short Introduction VERY SHORT INTRODUCTIONS are for anyone wanting a stimulating and accessible way into a new subject. They are written by experts, and have been translated into more than 40 different languages. The series began in 1995, and now covers a wide variety of topics in every discipline. The VSI library now contains over 450 volumes—a Very Short Introduction to everything from Indian philosophy to psychology and American history and relativity—and continues to grow in every subject area. Very Short Introductions available now: ACCOUNTING Christopher Nobes ANAESTHESIA Aidan O’Donnell ADOLESCENCE Peter K. Smith ANARCHISM Colin Ward ADVERTISING Winston Fletcher ANCIENT ASSYRIA Karen Radner AFRICAN AMERICAN RELIGION ANCIENT EGYPT Ian Shaw Eddie S. Glaude Jr ANCIENT EGYPTIAN ART AND AFRICAN HISTORY John Parker and ARCHITECTURE Christina Riggs Richard Rathbone ANCIENT GREECE Paul Cartledge AFRICAN RELIGIONS Jacob K. Olupona THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST AGNOSTICISM Robin Le Poidevin Amanda H. Podany AGRICULTURE Paul Brassley and ANCIENT PHILOSOPHY Julia Annas Richard Soffe ANCIENT WARFARE ALEXANDER THE GREAT Harry Sidebottom Hugh Bowden ANGELS David Albert Jones ALGEBRA Peter M. Higgins ANGLICANISM Mark Chapman AMERICAN HISTORY Paul S. Boyer THE ANGLO-SAXON AGE AMERICAN IMMIGRATION John Blair David A. Gerber THE ANIMAL KINGDOM AMERICAN LEGAL HISTORY Peter Holland G. Edward White ANIMAL RIGHTS David DeGrazia AMERICAN POLITICAL HISTORY THE ANTARCTIC Klaus Dodds Donald Critchlow ANTISEMITISM Steven Beller AMERICAN POLITICAL PARTIES ANXIETY Daniel Freeman and AND ELECTIONS L. Sandy Maisel Jason Freeman AMERICAN POLITICS THE APOCRYPHAL GOSPELS Richard M. Valelly Paul Foster THE AMERICAN PRESIDENCY ARCHAEOLOGY Paul Bahn Charles O. -

CASE REPORT the PATIENT 33-Year-Old Woman

CASE REPORT THE PATIENT 33-year-old woman SIGNS & SYMPTOMS – 6-day history of fever Katherine Lazet, DO; – Groin pain and swelling Stephanie Rutterbush, MD – Recent hiking trip in St. Vincent Ascension Colorado Health, Evansville, Ind (Dr. Lazet); Munson Healthcare Ostego Memorial Hospital, Lewiston, Mich (Dr. Rutterbush) [email protected] The authors reported no potential conflict of interest THE CASE relevant to this article. A 33-year-old Caucasian woman presented to the emergency department with a 6-day his- tory of fever (103°-104°F) and right groin pain and swelling. Associated symptoms included headache, diarrhea, malaise, weakness, nausea, cough, and anorexia. Upon presentation, she admitted to a recent hike on a bubonic plague–endemic trail in Colorado. Her vital signs were unremarkable, and the physical examination demonstrated normal findings except for tender, erythematous, nonfluctuant right inguinal lymphadenopathy. The patient was admitted for intractable pain and fever and started on intravenous cefoxitin 2 g IV every 8 hours and oral doxycycline 100 mg every 12 hours for pelvic inflammatory disease vs tick- or flea-borne illness. Due to the patient’s recent trip to a plague-infested area, our suspicion for Yersinia pestis infection was high. The patient’s work-up included a nega- tive pregnancy test and urinalysis. A com- FIGURE 1 plete blood count demonstrated a white CT scan from admission blood cell count of 8.6 (4.3-10.5) × 103/UL was revealing with a 3+ left shift and a platelet count of 112 (180-500) × 103/UL. A complete metabolic panel showed hypokalemia and hyponatremia (potassium 2.8 [3.5-5.1] mmol/L and sodium 134 [137-145] mmol/L). -

Br 1100S, Br 1300S

BR 1100S, BR 1300S PARTS LIST Standard Models After SN1000038925: 56413006(BR 1100S), 56413007(BR 1100S C / w/sweep system), 56413889(OBS / BR 1100S C / w/o sweep system) 56413010(BR 1300S), 56413011(BR 1300S C / w/sweep system), 56413890(OBS / BR 1300S C / w/o sweep system) Obsolete EDS Models: 56413785(BR 1100S EDS), 56413781(BR 1100S C EDS / w/sweep system), 56413782(BR 1300S EDS), 56413783(BR 1300S C EDS / w/sweep system), 56413897(BR 1100S C EDS / w/o sweep system) 56413898(BR 1300S C EDS / w/o sweep system) 5/08 revised 2/11 FORM NO. 56042498 08-5 TABLE OF CONTENTS 10-7 BR 1100S / BR 1300S 1 DESCRIPTION PAGE Chassis System ................................................................................................................................................. 2-3 Decal System ..................................................................................................................................................... 4-5 Drive Wheel System........................................................................................................................................... 6-7 Drive Wheel System (steering assembly) .......................................................................................................... 8-9 Electrical System.............................................................................................................................................10-11 Rear Wheel System ......................................................................................................................................