Relations Between Personality and Coping: a Meta-Analysis Jennifer K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

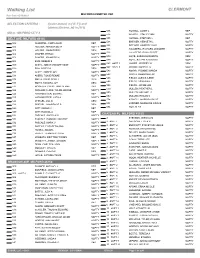

Walking List CLERMONT MILFORD EXEMPTED VSD Run Date:05/19/2021

Walking List CLERMONT MILFORD EXEMPTED VSD Run Date:05/19/2021 SELECTION CRITERIA : ({voter.status} in ['A','I']) and {district.District_id} in [112] 535 HOWELL, JANET L REP MD-A - MILFORD CITY A 535 HOWELL, STACY LYNN NOPTY BELT AVE MILFORD 45150 535 HOWELL, STEPHEN L REP 538 BREWER, KENNETH L NOPTY 502 KLOEPPEL, CODY ALAN REP 538 BREWER, KIMBERLY KAY NOPTY 505 HOLSER, AMANDA BETH NOPTY 538 HALLBERG, RICHARD LEANDER NOPTY 505 HOLSER, JOHN PERRY DEM 538 HALLBERG, RYAN SCOTT NOPTY 506 SHAFER, ETHAN NOPTY 539 HOYE, SARAH ELIZABETH DEM 506 SHAFER, JENNIFER M NOPTY 539 HOYE, STEPHEN MICHAEL NOPTY 508 BUIS, DEBBIE S NOPTY 542 #APT 1 LANIER, JEFFREY W DEM 509 WHITE, JONATHAN MATTHEW NOPTY 542 #APT 3 MASON, ROBERT G NOPTY 510 ROA, JOYCE A DEM 543 AMAYA, YVONNE WANDA NOPTY 513 WHITE, AMBER JOY NOPTY 543 NORTH, DEBORAH FAY NOPTY 514 AKERS, TONIE RENAE NOPTY 546 FIELDS, ALEXIS ILENE NOPTY 518 SMITH, DAVID SCOTT DEM 546 FIELDS, DEBORAH J NOPTY 518 SMITH, TAMARA JOY DEM 546 FIELDS, JACOB LEE NOPTY 521 MCBEATH, COURTTANY ALENE REP 550 MULLEN, HEATHER L NOPTY 522 DUNHAM CLARK, WILMA LOUISE NOPTY 550 MULLEN, MICHAEL F NOPTY 525 HACKMEISTER, EDWIN L REP 550 MULLEN, REGAN N NOPTY 525 HACKMEISTER, JUDY A NOPTY 554 KIDWELL, MARISSA PAIGE NOPTY 526 SPIEGEL, JILL D DEM 554 LINDNER, MADELINE GRACE NOPTY 526 SPIEGEL, LAWRENCE B DEM 554 ROA, ALEX NOPTY 529 WITT, AARON C REP 529 WITT, RACHEL A REP CHATEAU PL MILFORD 45150 532 PASCALE, ANGELA W NOPTY 532 PASCALE, DOMINIC VINCENT NOPTY 2 STEVENS, JESSICA M NOPTY 532 PASCALE, MARK V NOPTY 2 #APT 1 CHURCHILL, REX -

Pay-Per-View

Pay-Per-View Don’t bother with the babysitter. Stop worrying about traffic. Because with Pay Per View, you get the best seats in the house without ever leaving home. From UFC fights to exclusive concerts, watch the best in live sports and entertainment right on your own TV. Ordering made easy No need to call or go online. Just order with your remote. From the Guide menu, go to the Pay Per View event channel (PPV) to see what’s playing this month. Once you’ve made your selection, all you need to do is select “Watch” and then confirm your order. It’s that easy. What’s new this month? UFC 264: Poirier vs McGregor 3 July 10th, 2021, 10:00 p.m. ET / 7:00 p.m. PT The final chapter in the trilogy between Dustin Poirier and Conor McGregor will be written on Saturday, July 10, as the lightweight superstars settle the score in the main event of UFC 264 at T-Mobile Arena in Las Vegas. After Ireland's McGregor defeated Poirier in 2014, Louisiana's "Diamond" evened the score in January, setting up the most highly anticipated rubber match in UFC history between former champions determined to be the one leaving this trilogy victorious. SD standard definition $64.99 HD high definition $64.99 Channels 324 and 611 (BlueCurve TV SD) Channels 300 and 601 (BlueCurve TV HD) Replays: Available until July 25th, 2021 Ring Of Honor: Best In The World 2021 July 11h, 2021, 8:00 p.m. ET / 5:00 p.m. -

Baby Boy Names Registered in 2017

Page 1 of 43 Baby Boy Names Registered in 2017 # Baby Boy Names # Baby Boy Names # Baby Boy Names 1 Aaban 3 Abbas 1 Abhigyan 1 Aadam 2 Abd 2 Abhijot 1 Aaden 1 Abdaleh 1 Abhinav 1 Aadhith 3 Abdalla 1 Abhir 2 Aadi 4 Abdallah 1 Abhiraj 2 Aadil 1 Abd-AlMoez 1 Abic 1 Aadish 1 Abd-Alrahman 1 Abin 2 Aaditya 1 Abdelatif 1 Abir 2 Aadvik 1 Abdelaziz 11 Abraham 1 Aafiq 1 Abdelmonem 7 Abram 1 Aaftaab 1 Abdelrhman 1 Abrham 1 Aagam 1 Abdi 1 Abrielle 2 Aahil 1 Abdihafid 1 Absaar 1 Aaman 2 Abdikarim 1 Absalom 1 Aamir 1 Abdikhabir 1 Abu 1 Aanav 1 Abdilahi 1 Abubacarr 24 Aarav 1 Abdinasir 1 Abubakar 1 Aaravjot 1 Abdi-Raheem 2 Abubakr 1 Aarez 7 Abdirahman 2 Abu-Bakr 1 Aaric 1 Abdirisaq 1 Abubeker 1 Aarish 2 Abdirizak 1 Abuoi 1 Aarit 1 Abdisamad 1 Abyan 1 Aariv 1 Abdishakur 13 Ace 1 Aariyan 1 Abdiziz 1 Achier 2 Aariz 2 Abdoul 4 Achilles 2 Aarnav 2 Abdoulaye 1 Achyut 1 Aaro 1 Abdourahman 1 Adab 68 Aaron 10 Abdul 1 Adabjot 1 Aaron-Clive 1 Abdulahad 1 Adalius 2 Aarsh 1 Abdul-Azeem 133 Adam 1 Aarudh 1 Abdulaziz 2 Adama 1 Aarus 1 Abdulbasit 1 Adamas 4 Aarush 1 Abdulla 1 Adarius 1 Aarvsh 19 Abdullah 1 Adden 9 Aaryan 5 Abdullahi 4 Addison 1 Aaryansh 1 Abdulmuhsin 1 Adedayo 1 Aaryav 1 Abdul-Muqsit 1 Adeel 1 Aaryn 1 Abdulrahim 1 Adeen 1 Aashir 2 Abdulrahman 1 Adeendra 1 Aashish 1 Abdul-Rahman 1 Adekayode 2 Aasim 1 Abdulsattar 4 Adel 1 Aaven 2 Abdur 1 Ademidesireoluwa 1 Aavish 1 Abdur-Rahman 1 Ademidun 3 Aayan 1 Abe 5 Aden 1 Aayandeep 1 Abed 1 A'den 1 Aayansh 21 Abel 1 Adeoluwa 1 Abaan 1 Abenzer 1 Adetola 1 Abanoub 1 Abhaypratap 1 Adetunde 1 Abantsia 1 Abheytej 3 -

Stan Douglas Born 1960 in Vancouver

David Zwirner This document was updated December 12, 2019. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. Stan Douglas Born 1960 in Vancouver. Lives and works in Vancouver. EDUCATION 1982 Emily Carr College of Art, Vancouver SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2020 Stan Douglas: Doppelgänger, David Zwirner, New York, concurrently on view at Victoria Miro, London 2019 Stan Douglas: SPLICING BLOCK, Julia Stoschek Collection (JSC), Berlin [collection display] 2018 Stan Douglas: DCTs and Scenes from the Blackout, David Zwirner, New York 2017 Stan Douglas, Victoria Miro, London Stan Douglas: Luanda-Kinshasa, Les Champs Libres, Rennes, France 2016 Stan Douglas: Photographs, David Zwirner, New York Stan Douglas: The Secret Agent, David Zwirner, New York Stan Douglas: The Secret Agent, Salzburger Kunstverein, Salzburg [catalogue] Stan Douglas: Luanda-Kinshasa, Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM) Stan Douglas: The Secret Agent, Victoria Miro, London Stan Douglas, Hasselblad Center, Gothenburg, Sweden [organized on occasion of the artist receiving the 2016 Hasselblad Foundation International Award in Photography] [catalogue] 2015 Stan Douglas: Interregnum, Museu Coleção Berardo, Lisbon [catalogue] Stan Douglas: Interregnum, Wiels Centre d’Art Contemporain, Brussels [catalogue] 2014 Stan Douglas: Luanda-Kinshasa, David Zwirner, New York Stan Douglas: Scotiabank Photography Award, Ryerson Image Centre, Ryerson University, Toronto [catalogue published in 2013] Stan Douglas, The Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh [catalogue] -

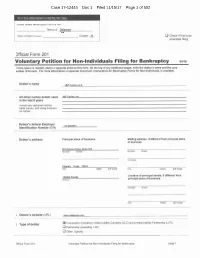

Case 17-12445 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 1 Of

Case 17-12445 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 1 of 502 Case 17-12445 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 2 of 502 Case 17-12445 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 3 of 502 Case 17-12445 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 4 of 502 Case 17-12445 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 5 of 502 Case 17-12445 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 6 of 502 Case 17-12445 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 7 of 502 Case 17-12445 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 8 of 502 Case 17-12445 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 9 of 502 Case 17-12445 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 10 of 502 Case 17-12445 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 11 of 502 Case 17-12445 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 12 of 502 Case 17-12445 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 13 of 502 Case 17-12445 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 14 of 502 Case 17-12445 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 15 of 502 Case 17-12445 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 16 of 502 Case 17-12445 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 17 of 502 Case 17-12445 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 18 of 502 Case 17-12445 Doc 1 Filed 11/15/17 Page 19 of 502 1 CYCLE CENTER H/D 1-ELEVEN INDUSTRIES 100 PERCENT 107 YEARICKS BLVD 3384 WHITE CAP DR 9630 AERO DR CENTRE HALL PA 16828 LAKE HAVASU CITY AZ 86406 SAN DIEGO CA 92123 100% SPPEDLAB LLC 120 INDUSTRIES 1520 MOTORSPORTS 9630 AERO DR GERALD DUFF 1520 L AVE SAN DIEGO CA 92123 30465 REMINGTON RD CAYCE SC 29033 CASTAIC CA 91384 1ST AMERICAN FIRE PROTECTION 1ST AYD CO 2 CLEAN P O BOX 2123 1325 GATEWAY DR PO BOX 161 MANSFIELD TX 76063-2123 ELGIN IN 60123 HEISSON WA 98622 2 WHEELS HEAVENLLC 2 X MOTORSPORTS 241 PRAXAIR DISTRIBUTION INC 2555 N FORSYTH RD STE A 1059 S COUNTRY CLUB DRRIVE DEPT LA 21511 ORLANDO FL 32807 MESA AZ -

Diplomatic List – Fall 2018

United States Department of State Diplomatic List Fall 2018 Preface This publication contains the names of the members of the diplomatic staffs of all bilateral missions and delegations (herein after “missions”) and their spouses. Members of the diplomatic staff are the members of the staff of the mission having diplomatic rank. These persons, with the exception of those identified by asterisks, enjoy full immunity under provisions of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations. Pertinent provisions of the Convention include the following: Article 29 The person of a diplomatic agent shall be inviolable. He shall not be liable to any form of arrest or detention. The receiving State shall treat him with due respect and shall take all appropriate steps to prevent any attack on his person, freedom, or dignity. Article 31 A diplomatic agent shall enjoy immunity from the criminal jurisdiction of the receiving State. He shall also enjoy immunity from its civil and administrative jurisdiction, except in the case of: (a) a real action relating to private immovable property situated in the territory of the receiving State, unless he holds it on behalf of the sending State for the purposes of the mission; (b) an action relating to succession in which the diplomatic agent is involved as an executor, administrator, heir or legatee as a private person and not on behalf of the sending State; (c) an action relating to any professional or commercial activity exercised by the diplomatic agent in the receiving State outside of his official functions. -- A diplomatic agent’s family members are entitled to the same immunities unless they are United States Nationals. -

Stan Douglas

STAN DOUGLAS Born 1960 in Vancouver, Canada Lives and works in Vancouver, Canada Education 1982 Emily Carr College of Art, Vancouver, Canada Solo Exhibitions th 2022 59 International Art Exhibition: La Biennale di Venezia, Canada Pavilion, Venice, Italy 2020 Doppelgänger, Victoria Miro, London, UK, concurrently on view at David Zwirner, New York, USA 2019 Stan Douglas: SPLICING BLOCK, Julia Stoschek Collection, Berlin, Germany Hors-Champs, Western Front, Vancouver, Canada 2018 Stan Douglas, MUDAM, Luxembourg City, Luxembourg Stan Douglas: DCT’s and Scenes from the Blackout, David Zwirner, New York, USA 2017 Stan Douglas, Victoria Miro, London, UK Stan Douglas: Luanda-Kinshasa, Les Champs Libres, Rennes, France 2016 Stan Douglas: Hasselblad Award 2016, Hasselblad Center, Gothenburg, Sweden Luanda-Kinshasa, Pérez Art Museum Miami, Florida, USA The Secret Agent, Salzburger Kunstverein, Salzburg, Austria The Secret Agent, David Zwirner, New York, USA Stan Douglas: Photographs, David Zwirner, New York, USA The Secret Agent, Victoria Miro, London, UK 2015 Interregnum, Museu Coleção Berardo, Lisbon, Portugal; Wiels Centre d’Art Contemporain, Brussels 2014 The Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh, Scotland Synthetic Pictures: Presentation House Gallery, Vancouver, Canada Scotiabank Photography Award: Stan Douglas, Ryerson Image Centre, Toronto, Canada Luanda-Kinshasa, David Zwirner, New York, USA 2013 Photography 2008 – 2013, Carré d’Art - Musée d’Art Contemporain, Nîmes, France; travelling to Haus -

New Documentary Examines Milford Graves' Music, Philosophy

MARCH 2018 VOLUME 85 / NUMBER 3 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Markus Stuckey Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Hawkins Editorial Intern Izzy Yellen ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Kevin R. Maher 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian, Michael -

Burlington Parks, Recreation & Waterfront Master Plan

BURLINGTON PARKS, RECREATION & WATERFRONT MASTER PLAN OCTOBER 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Mayor Miro Weinberger Jesse Bridges, Parks, Recreation & Waterfront Director and Harbormaster Jen Francis, Parks Comprehensive Planner City of Burlington Community BPRW Staff BPRW Leadership & Innovation Team Jesse Bridges, Parks, Recreation & Waterfront Director and Harbormaster Melissa Cate, Recreation Facilities Manager Jen Francis, Parks Comprehensive Planner Erin Moreau, Waterfront Manager Deryk Roach, Superintendent of Park Operations & Maintenance Gary Rogers, Superintendent of Recreation BPRW Commission John Bossange Carolyn Hanson Fauna Hurley Nancy Kaplan, Chair Jeetan Khadka Special thanks to former Commissioners Steve Allen, John Ewing, Dave Hartnett, and Chris Pearson and to former Recreation Superintendent Maggie Leugers. Key leadership positions within Burlington Parks, Recreation & Waterfront have been recently filled by fresh voices. The BPRW Master Plan takes advantage of this new perspective, aiming to create a unified voice for the multiple roles that parks fill in contemporary cities. At the same time, the plan builds on the integrity of past stewardship and integrates the exceptional work of staff in maintaining and programming our urban parks system. The expansive role of parks in Burlington’s urban environment is described in the following pages. This document was produced by the City of Burlington, Heller + Heller Consulting and Sasaki Associates. © 2015 City of Burlington. Parts of this publication may be reproduced. Please contact -

HHS the Dispatch

School Newspaper SSUE OLUME DISPATCH I II, V 46 HUNTINGTON HIGH SCHOOL OAKWOOD AND MCKAY ROADS HUNTINGTON, NY 11743 INSIDE THIS PAGE 2 PAGE 8 PAGE 15 January 2017 ISSUE: HELLO 2017 Index WANT TO SEND 2 Current Events 3 Sports | Advice SOMETHING IN? 4-5 Las Páginas in Español SUBMIT ANONYMOUS ADVICE QUESTIONS TO ROOM 252 6-7 School News 7-9 Op-Ed TWITTER REMIND 10-14 Year in Review 15 Opinion @HHSDISPATCH TEXT @HDISP TO 81010 16-18 Takes on the Election 18 Op-Ed 19 Puzzles FACEBOOK GROUP EMAIL 20 Entertainment @HHSDISPATCH [email protected] The Dispatch 2 January 6 Dispatch ACTRESS, AUTHOR, ICON CARRIE FISHER EDITOR-IN-CHIEF MAX ROBINS DIES AT AGE 60 in 1991, Sister Act in such as Ellen and The SENIOR EDITORS BY KATY DARA 1992, Lethal Weapon 3 Graham Norton Show. MICHELLE D’ALESSANDRO in 1992 and The Wed- Her death was sudden SARAH JAMES ding Singer in 1998. and unexpected. COPY EDITORS On Tuesday, Decem- Although Entertain- Carrie Fisher’s SABRINA FLORO ber 27th, 2016, Carrie ment Weekly called daughter, Catharine JACOB FULLER Fisher passed away. Carrie Fisher “one of “Billie” Lourd said, Star Wars STEVE YEH The actress the most sought af- “She was loved by SPANISH EDITOR suffered a heart attack ter doctors in town” the world and she ARIANA StrIEB on a flight from Lon- in 1992, she was not will be missed pro- SECRETARY don to Los Angeles credited by name as a foundly. Our entire NICOLE ARENTH on December 23rd. writer for any of the family thanks you for CONTRIBUTING STAFF First com- films in which she your thoughts and ing onto the scene TAZZ AKBER, EMANUEL ANASTOS, JONAH had a hand. -

Pay-Per-View

Pay-Per-View Don’t bother with the babysitter. Stop worrying about traffic. Because with Pay Per View, you get the best seats in the house without ever leaving home. From UFC fights to exclusive concerts, watch the best in live sports and entertainment right on your own TV. Ordering made easy No need to call or go online. Just order with your remote. From the Guide menu, go to the Pay Per View event channel (PPV) to see what’s playing this month. Once you’ve made your selection, all you need to do is select “Watch” and then confirm your order. It’s that easy. What’s new this month? Ring Of Honor: The Very Best of Death Before Dishonor (Taped Premiere) September 25th, 2020, 9:00 p.m. ET / 6:00 p.m. PT Don’t miss this unprecedented, acclaimed collection featuring some of the greatest matches in pro wrestling history! Stars CM Punk, Bryan Danielson, Tyler Black, Samoa Joe, Briscoes, Rush, Claudio Castagnoli, Nigel McGuinness and many more in action, plus the Cage of Death! SD standard definition $14.99 HD high definition $14.99 Channels 324 and 611 (BlueCurve TV SD) Channels 300 and 601 (BlueCurve TV HD) Replays: Available until December 18th, 2020 Impact Wrestling: Bound For Glory Live! 2020 October 24th, 2020, 8:00 p.m. ET / 5:00 p.m. PT On Saturday, October 24th, 2020 IMPACT Wrestling presents its biggest show of the year BOUND FOR GLORY 2020 from Nashville, Tennessee, featuring top stars Eddie Edwards, Moose, Ken Shamrock, Eric Young, Rich Swann, Luke Gallows, Karl Anderson, The Motor City Machine Guns, EC3, Sami Callihan, Rob Van Dam and Rhino, plus the Knockouts, including Champion Deonna Purrazzo, Kylie Rae, Jordynne Grace and more. -

The Influence of Children's Art on Joan Miró and Jean Dubuffet

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 1983 THE INFLUENCE OF CHILDREN'S ART ON JOAN MIRÓ AND JEAN DUBUFFET Linda L. Ferrell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/4572 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE INFLUENCE OF CHILDREN 'S ART ON JOAN MIR6 AND JEAN DUBUFFET by Linda L. Ferrell B.A. , Mary Washington College of the University of Virginia Submitted to the Faculty of the Schoo l of the Arts of Virginia Commonwealth Un iversity in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Richmond , Virginia December , 1983 Virginia Comm�nwealth University Library APPROVAL CERTIFICATE THE INFLUENCE OF CHILDREN 'S ART ON JOAN MI RO AND JEAN DUBUFFET by LINDA L. FERRELL Approved : Thesis Advisor De ade Graduate Committee 1airector of�adUate Studies Arts TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . iii Chapter I. ART OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY AND CHILDREN 'S ART ...... 1 II. THE STAGES OF DEVELOPMENT IN CHILDREN 'S ART . 17 III. JOAN MIRO AND CHILDREN 'S ART . 32 IV. JEAN DUBUFFET AND CHILDREN 'S ART . 52 V. CONCLUSION . 73 NOTES 86 BIBLIOGRAPHY. 96 ILLUSTRATIONS 100 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Gestalts which represent the probable 10 1 evolution of human fo rms from earlier scribbles .