RETHINKING EXTINCTION Toward a Less Gloomy Environmentalism by James K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tennessee's Extinct Species

Tennessee's Extinct Species The following species Birds: once occurred in Carolina parakeet Conuropsis carolinensis Ectopistes migratorius Tennessee and are now Passenger pigeon believed to be extinct. Mammals: Following this list are two Eastern elk species descriptions-one Fishes: describing the Carolina Harelip sucker parakeet and another describing the extinct Mussels: Acornshell Epioblasma haysiana freshwater mussels Angled riffleshell Epioblasma biemarginata of Tennessee. Cumberland leafshell Epioblasma stewardsoni Leafshell Epioblasma flexuosa Narrowcat's paw Epioblasma lenoir Rough rockshell Quadrula tuberosa Round combshell Epioblasma personata Sugarspoon Epioblasma arcaeformis Tennessee riffleshell Epioblasma propinqua Carolina Parakeet Status Habitat The Carolina parakeet is an The Carolina parakeet was found Learn rrwreabout extinct species. in riverine forests, cypress swamps, Tennessee's diverse and other woodlands over much of Description the Eastern and Midwest Regions of ecosyster.n3.Su~ort The Carolina parakeet was a the United States. It was the only conservation in your small parrot, about 12inches in parrot native to the United States. community and state! length. Its head was lemon yellow, The parakeets rested at night in with an orange forehead and cheeks. groups, with as many as 30 birds The rest of its body was green. Its sleeping inside one hollowtree, while legs and beak were pale pinkish- others would hang on the outside. white. These curious birds lived and Nests were placed in hollowtrees, traveled in flocks. and three to five white eggs were laid. Up to 50 nests were often crowded into one tree. Role in the Ecosystem Carolina parakeets enjoyed a variety of different foods-apples, peaches, mulberries, pecans, grapes, dogwood fruit, and grains. -

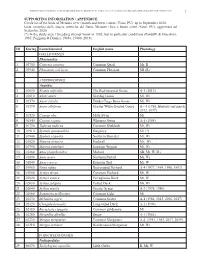

1 ID Euring Latin Binomial English Name Phenology Galliformes

BIRDS OF METAURO RIVER: A GREAT ORNITHOLOGICAL DIVERSITY IN A SMALL ITALIAN URBANIZING BIOTOPE, REQUIRING GREATER PROTECTION 1 SUPPORTING INFORMATION / APPENDICE Check list of the birds of Metauro river (mouth and lower course / Fano, PU), up to September 2020. Lista completa delle specie ornitiche del fiume Metauro (foce e basso corso /Fano, PU), aggiornata ad Settembre 2020. (*) In the study area 1 breeding attempt know in 1985, but in particolar conditions (Pandolfi & Giacchini, 1985; Poggiani & Dionisi, 1988a, 1988b, 2019). ID Euring Latin binomial English name Phenology GALLIFORMES Phasianidae 1 03700 Coturnix coturnix Common Quail Mr, B 2 03940 Phasianus colchicus Common Pheasant SB (R) ANSERIFORMES Anatidae 3 01690 Branta ruficollis The Red-breasted Goose A-1 (2012) 4 01610 Anser anser Greylag Goose Mi, Wi 5 01570 Anser fabalis Tundra/Taiga Bean Goose Mi, Wi 6 01590 Anser albifrons Greater White-fronted Goose A – 4 (1986, february and march 2012, 2017) 7 01520 Cygnus olor Mute Swan Mi 8 01540 Cygnus cygnus Whooper Swan A-1 (1984) 9 01730 Tadorna tadorna Common Shelduck Mr, Wi 10 01910 Spatula querquedula Garganey Mr (*) 11 01940 Spatula clypeata Northern Shoveler Mr, Wi 12 01820 Mareca strepera Gadwall Mr, Wi 13 01790 Mareca penelope Eurasian Wigeon Mr, Wi 14 01860 Anas platyrhynchos Mallard SB, Mr, W (R) 15 01890 Anas acuta Northern Pintail Mi, Wi 16 01840 Anas crecca Eurasian Teal Mr, W 17 01960 Netta rufina Red-crested Pochard A-4 (1977, 1994, 1996, 1997) 18 01980 Aythya ferina Common Pochard Mr, W 19 02020 Aythya nyroca Ferruginous -

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species Are Listed in Order of First Seeing Them ** H = Heard Only

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species are listed in order of first seeing them ** H = Heard Only July 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th 11th 12th 13th 14th 15th 16th 17th Mute Swan Cygnus olor X X X X X X X X Whopper Swan Cygnus cygnus X X X X Greylag Goose Anser anser X X X X X Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis X X X Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula X X X X Common Eider Somateria mollissima X X X X X X X X Common Goldeneye Bucephala clangula X X X X X X Red-breasted Merganser Mergus serrator X X X X X Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo X X X X X X X X X X Grey Heron Ardea cinerea X X X X X X X X X Western Marsh Harrier Circus aeruginosus X X X X White-tailed Eagle Haliaeetus albicilla X X X X Eurasian Coot Fulica atra X X X X X X X X Eurasian Oystercatcher Haematopus ostralegus X X X X X X X Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus X X X X X X X X X X X X European Herring Gull Larus argentatus X X X X X X X X X X X X Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus X X X X X X X X X X X X Great Black-backed Gull Larus marinus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common/Mew Gull Larus canus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Tern Sterna hirundo X X X X X X X X X X X X Arctic Tern Sterna paradisaea X X X X X X X Feral Pigeon ( Rock) Columba livia X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Wood Pigeon Columba palumbus X X X X X X X X X X X Eurasian Collared Dove Streptopelia decaocto X X X Common Swift Apus apus X X X X X X X X X X X X Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica X X X X X X X X X X X Common House Martin Delichon urbicum X X X X X X X X White Wagtail Motacilla alba X X -

Birdwatching Bingo Identification Sheet Hey Everyone! I Hope You Have Fun Playing Birdwatching Bingo with Your Family

Birdwatching Bingo Identification Sheet Hey Everyone! I hope you have fun playing Birdwatching Bingo with your family. You can even share it with friends and do it over social media. To help you on your adventure, here is an identification sheet with all the different birds listed on your bingo card. With the help of this sheet and some binoculars, you will be on your way to becoming a fantastic birdwatcher. Most of these birds you can see visiting a birdfeeder, but some you might have to go on a walk and look for with a parent. To play, download and print the bingo cards for each player. Using pennies, pieces of paper, or even a pencil, mark the card when you see and identify the different birds. Don’t be frustrated if you don’t finish the game in one sitting, this game might be completed over a couple days. A great tool to help with IDing birds is the app MERLIN. This is a free bird ID app for your phone from the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology. The website, www.allaboutbirds.org, is a great source too. Blue Jay - Scientific Name: Cyanocitta cristata - Identifiable Markings: o Blue above, light grey below. Black and white markings on wings and tail. Larger than a robin, smaller than a crow. Crest and long tail. - Photo: Females/Males Look Similar Brown-headed Cowbird - Scientific Name: Molothrus ater - Identifiable Markings: o Stout bill. Short tail and stocky body. Males are glossy black with chocolate brown head. Females are grey-brown overall, without bold streaks, but slightly paler throat. -

Assessing the Extinction Probability of the Purple-Winged Ground Dove, an Enigmatic Bamboo Specialist

fevo-09-624959 April 29, 2021 Time: 12:42 # 1 ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 29 April 2021 doi: 10.3389/fevo.2021.624959 Assessing the Extinction Probability of the Purple-winged Ground Dove, an Enigmatic Bamboo Specialist Alexander C. Lees1,2*, Christian Devenish1, Juan Ignacio Areta3, Carlos Barros de Araújo4,5, Carlos Keller6, Ben Phalan7 and Luís Fábio Silveira8 1 Ecology and Environment Research Centre (EERC), Department of Natural Sciences, Manchester Metropolitan University, Manchester, United Kingdom, 2 Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, United States, 3 Laboratorio de Ecología, Comportamiento y Sonidos Naturales, Instituto de Bio y Geociencias del Noroeste Argentino (IBIGEO-CONICET), Salta, Argentina, 4 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia e Monitoramento Ambiental, Centro de Ciências Aplicadas e Educação, Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Rio Tinto, Brazil, 5 Programa de Pós-graduação em Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Estadual de Londrina, Londrina, Brazil, 6 Independent Researcher, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 7 Centre for Conservation of Atlantic Forest Birds, Parque das Aves, Foz do Iguaçu, Brazil, 8 Seção de Aves, Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil The continued loss, fragmentation, and degradation of forest habitats are driving an Edited by: extinction crisis for tropical and subtropical bird species. This loss is particularly acute in Bruktawit Abdu Mahamued, the Atlantic Forest of South America, where it is unclear whether several endemic bird Kotebe Metropolitan University (KMU), Ethiopia species are extinct or extant. We collate and model spatiotemporal distributional data Reviewed by: for one such “lost” species, the Purple-winged Ground Dove Paraclaravis geoffroyi, John Woinarski, a Critically Endangered endemic of the Atlantic Forest biome, which is nomadic Charles Darwin University, Australia Sam Turvey, and apparently dependent on masting bamboo stands. -

Are European Starlings Breeding in the Azores Archipelago Genetically Distinct from Birds Breeding in Mainland Europe? Verónica C

Are European starlings breeding in the Azores archipelago genetically distinct from birds breeding in mainland Europe? Verónica C. Neves, Kate Griffiths, Fiona R. Savory, Robert W. Furness, Barbara K. Mable To cite this version: Verónica C. Neves, Kate Griffiths, Fiona R. Savory, Robert W. Furness, Barbara K. Mable. Are European starlings breeding in the Azores archipelago genetically distinct from birds breeding in mainland Europe?. European Journal of Wildlife Research, Springer Verlag, 2009, 56 (1), pp.95-100. 10.1007/s10344-009-0316-x. hal-00535248 HAL Id: hal-00535248 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00535248 Submitted on 11 Nov 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Eur J Wildl Res (2010) 56:95–100 DOI 10.1007/s10344-009-0316-x SHORT COMMUNICATION Are European starlings breeding in the Azores archipelago genetically distinct from birds breeding in mainland Europe? Verónica C. Neves & Kate Griffiths & Fiona R. Savory & Robert W. Furness & Barbara K. Mable Received: 6 May 2009 /Revised: 5 August 2009 /Accepted: 11 August 2009 /Published online: 29 August 2009 # Springer-Verlag 2009 Abstract The European starling (Sturnus vulgaris) has Keywords Azores . -

Niche Analysis and Conservation of Bird Species Using Urban Core Areas

sustainability Article Niche Analysis and Conservation of Bird Species Using Urban Core Areas Vasilios Liordos 1,* , Jukka Jokimäki 2 , Marja-Liisa Kaisanlahti-Jokimäki 2, Evangelos Valsamidis 1 and Vasileios J. Kontsiotis 1 1 Department of Forest and Natural Environment Sciences, International Hellenic University, 66100 Drama, Greece; [email protected] (E.V.); [email protected] (V.J.K.) 2 Arctic Centre, University of Lapland, 96101 Rovaniemi, Finland; jukka.jokimaki@ulapland.fi (J.J.); marja-liisa.kaisanlahti@ulapland.fi (M.-L.K.-J.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Knowing the ecological requirements of bird species is essential for their successful con- servation. We studied the niche characteristics of birds in managed small-sized green spaces in the urban core areas of southern (Kavala, Greece) and northern Europe (Rovaniemi, Finland), during the breeding season, based on a set of 16 environmental variables and using Outlying Mean Index, a multivariate ordination technique. Overall, 26 bird species in Kavala and 15 in Rovaniemi were recorded in more than 5% of the green spaces and were used in detailed analyses. In both areas, bird species occupied different niches of varying marginality and breadth, indicating varying responses to urban environmental conditions. Birds showed high specialization in niche position, with 12 species in Kavala (46.2%) and six species in Rovaniemi (40.0%) having marginal niches. Niche breadth was narrower in Rovaniemi than in Kavala. Species in both communities were more strongly associated either with large green spaces located further away from the city center and having a high vegetation cover (urban adapters; e.g., Common Chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs), European Greenfinch (Chloris Citation: Liordos, V.; Jokimäki, J.; chloris Cyanistes caeruleus Kaisanlahti-Jokimäki, M.-L.; ), Eurasian Blue Tit ( )) or with green spaces located closer to the city center Valsamidis, E.; Kontsiotis, V.J. -

Science for Saving Species Research Findings Factsheet Project 4.2

Science for Saving Species Research findings factsheet Project 4.2 Assessing the impacts of invasive species: Hollow-nesting birds in Tasmania In brief Background Predicting the impacts of invasive Invasive alien birds are found explore the known and theoretical species is difficult at large spatial across many areas of Australia. interaction network between the scales. This is because the interactions Many of these introduced birds cavity breeding birds in Tasmania, between invasive species and native use cavities, an important breeding and to identify which native species species vary across different species, resource for cavity nesting species. are likely impacted by the addition between different locations, over In Tasmania alone there are 27 of non-native species. time and in relation to other pressures species of hollow-nesting birds, We discovered that, overall, such as habitat loss, extensive fires, including three threatened species native hollow-nesting species climatic events and drought. and seven invasive hollow-nesting are likely facing increased levels bird species. The logging of big old Given that conservation and of competition for nesting sites trees with cavities and the addition management work is almost always as a result of non-native species of invasive species has likely led conducted under limited budgets and introductions. Such competition to increased competition over time, being able to quantify where is likely to decrease breeding the limited resource. However, and when invasive species are having opportunities for native species, the impact of most of these a significant impact on local species including some of Tasmania’s invasive species has not been is vital for effectively managing and threatened and endemic species. -

On the Preservation of the Beak in Confuciusornis (Aves: Pygostylia)

diversity Article On the Preservation of the Beak in Confuciusornis (Aves: Pygostylia) Amanda Falk 1, Jingmai O’Connor 2,3,* , Min Wang 2,3 and Zhonghe Zhou 2,3,* 1 Biology Department, Centre College, 600 W. Walnut St. Danville, KY 40422, USA; [email protected] 2 Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Beijing 100044, China; [email protected] 3 CAS Center for Excellence in Life and Paleoenvironment, Beijing 10010, China * Correspondence: [email protected] (J.O.); [email protected] (Z.Z.) Received: 27 October 2019; Accepted: 10 November 2019; Published: 11 November 2019 Abstract: The Confuciusornithiformes represent the most stem-ward avian occurrence of an edentulous rostrum. Although a keratinous beak is widely considered to have covered the rostrum in confuciusornithiforms, this feature is almost never preserved, having been previously reported only in the holotype of Confuciusornis dui and the holotype of Eoconfuciusornis zhengi. This strongly contrasts with the widespread preservation of the keratinous sheaths that cover the manual and pedal ungual phalanges. Here, we report on a third occurrence of a preserved rhamphotheca in a specimen of Confuciusornis sanctus. We illuminated the preserved traces using laser-stimulated fluorescence. Similarly to E. zhengi, the rhamphotheca has been preserved only as a two-dimensional trace, whereas ungual sheaths are preserved in three dimensions. In contrast to the traces preserved in C. dui, the rhamphotheca in the discussed specimen of C. sanctus is straight rather than upturned. This hints towards hidden morphological diversity within the thousands of Confuciusornis specimens, in which species may be further differentiated by soft tissue features or behaviors, much like many living birds, that cannot be detected in fossils, even with exceptional preservation. -

The Expressions of Emotion in the Pigeons. Iii. the Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes Migra Torius Linn.)

408 CaAm,Emotion in thePassenger Pigeon. [oct.[Auk THE EXPRESSIONS OF EMOTION IN THE PIGEONS. III. THE PASSENGER PIGEON (ECTOPISTES MIGRA TORIUS LINN.). BY WALLACE CRAIG. INTRODUCTION. IF the PassengerPigeon is not yet extinct,it is highlyimportant that there be publishedan accountof its peculiarvoice, for this may be of great assistancein re-discoveringthe birds. Thus, if you tell a boy to look for a bird of the samegeneral appearance as the Mourning Dove but larger, he will be sure to mistake some large-appearingMourning Dove for the PassengerPigeon. But tell him to look for a pigeonthat shrieksand chattersand clucks insteadof cooing,and the boy will be lesslikely to make a mistake. The voice has this further advantageas a mark of identification, that it cannotbe producedin a deadbird, and thus formsan incen- tive to keep the bird alive. If the speciesis extinct,it ismequallyimportant to publishwhat- ever is known of its voice,as a matter of permanentrecord. The PassengerPigeon is well known to have been a unique species in one respect--its prodigiousgregariousness. But the fact is that it was a marked bird in every respect. Eetopistesrepre- sentsa line of evolutionwhich has divergedwidely, in habits at least, from the main paths of Columbinedescent. Its voicewas more distinctivethan that of any other speciesin ProfessorWhit- man'slarge collection of living pigeonsfrom all parts of the world. This markedpeculiarity of the speciesmakes it infinitelyregrettable if the wholerace, throughsheer wantonness, has been annihilated. The accountshitherto published of the voiceand mating behavior of the PassengerPigeon are meagre,largely incorrect,and totally inadequatefor that detailed comparativestudy which scientific considerationsdemand. -

Gone Forever a Contemporary Look at the Extinction of the Passenger

POPULATION ECOLOGY Gone forever Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius)HREEHUNDRED wasYEARS the AGO, world'sTHE mostabundant land bird. Althoughfound only in easternNorth America, it num- beredthree to five billion,accounting for about a quarter of all North American landbirds. Passenger Pigeons traveled in flocks of hundredsof millions, at times obscuringthe sun. More than a century haspassed since the lastgigantic nesting colonies,and over seventyyears since the deathof the last PassengerPigeon, Martha,in the CincinnatiZoo. Although therehas been much speculationabout the extinctionof the PassengerPigeon sincethat time, mostof the proposedex- planationsare inadequate. The PassengerPigeon was never seri- ouslystudied while it still existedand the publishedaccounts are incompleteand oftencontradictory. Most of ourinforma- tion comesfrom reportsin the scientific and popular literature of the late nine- teenthand early twentiethcenturies. Lit- tle hasbeen written about the Passenger Pigeon'srole asan importantcomponent of the easterndeciduous forest ecosys- tem. Its reproductivebehavior exploited the mastfruiting of thesetrees, which in Photo/TheBell Museumof Natural History. turnsupported the tremendousPassenger Pigeonpopulations. One of the keys to the bird's successlay in its ability to nu- mericallyoverwhelm its predators. The precipitousdecline of the Passen- A contemporary look ger Pigeonfrom 1871 to 1880, and the birds' subsequentextinction, was an in- escapabledemographic consequence of at the extinction the relentlessdisruption -

416 Common Starling Put Your Logo Here

Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze Sponsor is needed. Write your name here 416 Common Starling Put your logo here Common Starling. Spring. Adult. Male (23-V). COMMON STARLING (Sturnus vulga- ris ) IDENTIFICATION Common Starling. 20-22 cm. Black plumage, with purple, green Spring. Adult. Pattern of and blue gloss in breeding plumage; strongly wing, breast and upper- spotted pale in winter; yellow bill in breeders, parts. dark in winter; short tail. Wing formula : the 9th primary is the longest (sometimes 8th and 9th similar). Juveniles are grey brown; pale superci- lium poorly pronounced; cheek mottled dark. 9ª 8ª 9ª 8ª 7ª 7ª Common Starling. Juvenile. Wing formula and head pattern. Common Starling. Win- ter. Wing formula and pattern of breast and upperparts. http://blascozumeta.com Write your website here Page 1 Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze Sponsor is needed. Write your name here 416 Common Starling Put your logo here SIMILAR SPECIES Recalls that of a male Blackbird which has lon- ger tail and lacks glossy plumage or white spots. Spotless Starling is very similar but lacks green and purple gloss in breeding plumage and wing feathers lacks buff edges. Juvenile of Spotless Starling is almost indistinguishable by plumage but with pale supercilium quite pro- nounced and cheek poorly mottled dark; wing formula is different being the 8th primary the Spotless Starling. 9ª Blackbird. Male 8 7 Spotless Starling. Winter. Spotless Starling. Juvenile.Wing formula and head pattern. 9ª 8ª SEXING In breeding season, base of the lower mandible is 7ª grey-blue in males and white-pinkish in females .