Brycheiniog 2006:44036 Brycheiniog 2005 28/4/16 08:11 Page 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Residential Allocations Settlement Site Code Site Name Brecon B15

Residential Allocations Settlement Site Code Site Name Brecon B15 Cwmfalldau Fields (Under construction) CS28 Cwmfalldau fields extension CS93 Slwch House Field CS132 UDP allocation B17 opposite High School, North of Hospital (Mixed Use site of which 4.55ha is allocated for housing) DBR-BR-A Site located to the North of Camden Crescent and to the East of the Breconshire War Memorial Hospital DBR-BR-B Site located to the north of Cradoc Close and west of Maen-du Well Crickhowell DBR-CR-A Land above Televillage Hay-on-Wye DBR-HOW-A Land opposite The Meadows DBR-HOW-C Land adjacent to Fire Station DBR-HOW-K Land adjacent to Caemawr Cottages CS136 UDP allocation H6 Former Health Centre Sennybridge & Defynnog SALT 002/092 Land at Castle Farm CS138 Glannau Senni Talgarth T9 UDP allocation Land North of Doctors Surgery CS137 Hay Road (Mixed Use site of which 0.75ha is allocated for housing) Bwlch DBR-BCH-J Land adjacent to Bwlch Woods Crai CS43 Land SW of Gwalia CS42 Land at Crai Gilwern CS102 Lancaster Drive (Former UDP allocation GW2) Govilon CS39/69/70/ Land at Ty Clyd 88/89/99 Libanus DBR-LIB-E Land adjacent Pen y Fan Close Llanbedr DBR-LBD-A Land adjacent to St Peter’s Close Llanfihangel DBR-LC-D Land opposite Pen-y-Dre Farm Crucorney Llanigon DBR-LGN-D Land opposite Llanigon County Primary School Llanspyddid DBR-LPD-A Land off Heol St Cattwg Pencelli CS120 Land south of Ty Melys Pennorth DBR-PNT-D Land adjacent to Ambelside Ponsticill CS91 Land to the West of Pontsicill House, Pontsticill CS55 Land adjacent to Penygarn DBR-PSTC-C Land at end of Dan-y-Coed CS139 UDP allocation PST1 adj. -

Brycheiniog Vol 42:44036 Brycheiniog 2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 1

68531_Brycheiniog_Vol_42:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 1 BRYCHEINIOG Cyfnodolyn Cymdeithas Brycheiniog The Journal of the Brecknock Society CYFROL/VOLUME XLII 2011 Golygydd/Editor BRYNACH PARRI Cyhoeddwyr/Publishers CYMDEITHAS BRYCHEINIOG A CHYFEILLION YR AMGUEDDFA THE BRECKNOCK SOCIETY AND MUSEUM FRIENDS 68531_Brycheiniog_Vol_42:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 2 CYMDEITHAS BRYCHEINIOG a CHYFEILLION YR AMGUEDDFA THE BRECKNOCK SOCIETY and MUSEUM FRIENDS SWYDDOGION/OFFICERS Llywydd/President Mr K. Jones Cadeirydd/Chairman Mr J. Gibbs Ysgrifennydd Anrhydeddus/Honorary Secretary Miss H. Gichard Aelodaeth/Membership Mrs S. Fawcett-Gandy Trysorydd/Treasurer Mr A. J. Bell Archwilydd/Auditor Mrs W. Camp Golygydd/Editor Mr Brynach Parri Golygydd Cynorthwyol/Assistant Editor Mr P. W. Jenkins Curadur Amgueddfa Brycheiniog/Curator of the Brecknock Museum Mr N. Blackamoor Pob Gohebiaeth: All Correspondence: Cymdeithas Brycheiniog, Brecknock Society, Amgueddfa Brycheiniog, Brecknock Museum, Rhodfa’r Capten, Captain’s Walk, Aberhonddu, Brecon, Powys LD3 7DS Powys LD3 7DS Ôl-rifynnau/Back numbers Mr Peter Jenkins Erthyglau a llyfrau am olygiaeth/Articles and books for review Mr Brynach Parri © Oni nodir fel arall, Cymdeithas Brycheiniog a Chyfeillion yr Amgueddfa piau hawlfraint yr erthyglau yn y rhifyn hwn © Except where otherwise noted, copyright of material published in this issue is vested in the Brecknock Society & Museum Friends 68531_Brycheiniog_Vol_42:44036_Brycheiniog_2005 28/2/11 10:18 Page 3 CYNNWYS/CONTENTS Swyddogion/Officers -

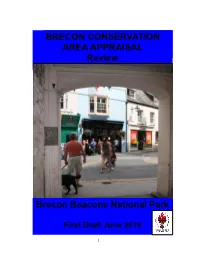

First Draft June 2016

BRECONBRECON CONSERVATION CONSERVATION AREAAREA APPRAISAL APPRAISAL Review Brecon Beacons National Park First Draft June 2016 1 BRECON CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Review of the Conservation Area Boundary 1 3 Community Involvement 5 4 The Planning Policy Context 5 5 Location and Context 6 6 Historic Development and Archaeology 7 7 Character Assessment 11 7.1 Quality of Place 11 7.2 Landscape Setting 12 7.3 Patterns of Use 13 7.4 Movement 14 7.5 Views and Vistas 15 7.6 Settlement Form 16 7.7 Character Areas 19 7.8 Scale 19 7.9 Landmark Buildings 20 7.10 Local Building Patterns 21 7.11 Materials 24 7.12 Architectural Detailing 25 7.13 Landscape/ streetscape 28 8 Important Local Buildings 33 9 Issues and Opportunities 34 10 Summary of Issues 39 11 Local Guidance and Management Proposals 40 12 Contact Details 42 13 Bibliography 42 14 Glossary of Architectural Terms 43 Appendices 2 1. Introduction 1.1 Section 69 of the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 imposes a duty on Local Planning Authorities to determine from time to time which parts of their area are ‘areas of special architectural or historic interest, the character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance’ and to designate these areas as conservation areas. The central area and historic suburbs of Brecon comprise one of four designated conservation areas in the National Park. The Brecon Conservation Area was designated by the National Park Authority on the 12th June 1970. 1.2 Planning authorities have a duty to protect these areas from development which would harm their special historic or architectural character and this is reflected in the policies contained in the National Park’s Local Development Plan. -

Emma Beynon by the Wye, Aberedw, Builth Wells, Powys. LD2 3UH

Emma Beynon By The Wye, Aberedw, Builth Wells, Powys. LD2 3UH. 07722170782 [email protected] https://emmabeynoncreativewriting.com Creative Writing Facilitation/ Fundraising / Evaluation / Teaching / Writing From November 2020 to present: leading creative writing workshops for Health and Wellbeing on Zoom for Radiate Arts https://www.radiatearts.co.uk as well as leading volunteer workshops for Mid and North Powys Mind and Pontypridd High School. November 2020 – March 2021: leading a Social Prescribing Creative Writing Project as part of Open Ground Writing for Judges Lodgings’, Presteigne. https://emmabeynoncreativewriting.com/open-ground February to December 2020 : Fundraising for Shakespeare Link https://www.shakespearelink.org.uk successful applications include: Arts Council Wales, D’Oyly Carte and Gwendoline Margaret Trust. January – February 2020: leading song writing workshops for pupils at Brecon High School, Wales. November 2019: leading Creative Writing Workshops for staff and pupils in Sadhguru School, Kibale Uganda. September 2013 to 2019 Project Manager Caban Sgriblio, Peak, https://peak.cymru/caban- sgriblio/ leading creative writing workshops for young people to develop health and well- being throughout Powys and The Valleys. This project was funded by BBC Children in Need. Duties Included: • Leading creative writing workshops for young people in the community • Collaborating with artists and film makers in the development of cross arts provision • Project evaluation & report writing, fundraising, hosting arts events and interviewing writers January 2008 –2012 May: Creative Writing Project Manager for The Write Team Bath Festivals, funded by The Paul Hamlyn Foundation. • Collaborating with writers and teaching creative writing & drama workshops in primary and secondary schools in Bath & North East Somerset. -

Facebook: Facebook.Com/Serenbooks Twitter: @Serenbooks

C o Distribution Wales Distribution & representation v e r england, scotland, ireland, europe Welsh books Council i m Central books ltd, 99 Wallis road uned 16, stad Glanyrafon, llanbadarn, a g e : london, e9 5ln aberystwyth sY23 3aQ s t i l phone 0845 458 9911 Fax 0845 458 9912 phone 01970 624455 Fax 01970 625506 l f r [email protected] [email protected] o m sales and Marketing Manager: tom Ferris T h representation e [email protected] G inpress ltd o s p Churchill house, 12 Mosley street, e l o newcastle upon tyne, ne1 1De north aMeriCa Distribution & f U s www.inpressbooks.co.uk representation d i r . phone 0191 230 8104 independent publishers Group D a Managing Director: rachael ogden 814 north Franklin street v e [email protected] Chicago il60610 M c K sales and Marketing : James hogg phone (312) 337 0747 Fax (312) 337 5985 e a [email protected] [email protected] n seren, 57 nolton street, bridgend, CF31 3ae 01656 663018 [email protected] www.serenbooks.com Facebook: facebook.com/serenbooks twitter: @serenbooks publisher: Mick Felton sales and Marketing: simon hicks Marketing: Victoria humphreys Fiction editor: penny thomas poetry editor: amy Wack poetry Wales: robin Grossmann, rebecca parfitt Directors: Cary archard (Founder and patron), John barnie, Duncan Campbell, robert edge, richard houdmont (Chair), patrick McGuinness, linda osborn (secretary), sioned puw rowlands, Christopher Ward no. 2262728. Vat no. Gb484323148. seren is the imprint of poetry Wales press ltd, which works with the financial assistance of the Welsh books Council www.serenbooks.com Preface 3 2011 was an exciting year in which we celebrated our 30th birthday and threw a street Cynan Jones Bird, Blood, Snow 4 party outside the seren offices on the sunniest october saturday since records began. -

LLYWELYN TOUR Builth Castle, SO 043511

Return to Aberedw and follow the road to Builth Wells Ffynnon Llywelyn is reached by descending the LLYWELYN TOUR Builth Castle, SO 043511. LD2 3EG This is steps at the western end of the memorial. Tradition has A Self Drive Tour to visit the reached by a footpath from the Lion Hotel, at the south- it that Llywelyn's head was washed here before being places connected with the death ern end of the Wye Bridge. There are the remains of a taken to the king at Rhuddlan. of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, sophisticated and expensive castle, rebuilt by Edward in Take the A483 back to Builth and then northwards Prince of Wales 1256 – 1282 1277. John Giffard was Constable of the castle in 1282 through Llandrindod and Crossgates. 2 miles north of and host to Roger le Strange, the commander of the this turn left for Abbey Cwmhir LD1 6PH. In the cen- King's squadron and Edmund Mortimer. INTRODUCTION tre of the village park in the area provided at Home Farm and walk down past the farmhouse to the ruins of Where was he killed? There are two very different the abbey. accounts of how Llywelyn died. The one most widely Llywelyn Memorial Stone SO 056712. This was accepted in outline by many English historians is that of Walter of Guisborough, written eighteen years after the placed in the ruins in 1978 near the spot where the grave is thought to lie. In 1876 English Court Records event, at the time of the crowning of the first English Prince of Wales in 1301. -

Gwydir Family

THE HISTORY OF THE GWYDIR FAMILY, WRITTEN BY SIR JOHN WYNNE, KNT. AND BART., UT CREDITUR, & PATET. OSWESTRY: \VOODJ\LL i\KD VENABLES, OS\VALD ROAD. 1878. WOODALL AND VENABLES, PRINTERS, BAILEY-HEAD AND OSWALD-ROAD. OSWESTRY. TO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE CLEMENTINA ELIZABETH, {!N HER OWN lHGHT) BARONESS WILLOUGHBY DE ERESBY, THE REPRESENTATIVE OF 'l'HE OLD GWYDIR STOCK AND THE OWNER OF THE ESTATE; THE FOURTEENTH WHO HAS BORNE THAT ANCIENT BARONY: THIS EDITION OF THE HISTORY OF THE GWYDIR FAMILY IS, BY PERMISSION, RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED BY THE PUBLISHERS. OSWALD ROAD, OSWESTRY, 1878. PREFACE F all the works which have been written relating to the general or family history O of North Wales, none have been for centuries more esteemed than the History of the Gwydir Family. The Hon. Daines Barrington, in his preface to his first edition of the work, published in 1770, has well said, "The MS. hath, for above.a cent~ry, been so prized in North Wales, that many in those parts have thought it worth while to make fair and complete transcripts of it." Of these transcripts the earliest known to exist is one in the Library at Brogyntyn. It was probably written within 45 years of the death of the author; but besides that, it contains a great number of notes and additions of nearly the same date, which have never yet appeared in print. The History of the Gwydir Family has been thrice published. The first editiun, edited by the Hon. Daines Barrington, issued from the press in 1770. The second was published in Mr. -

IV. the Cantrefs of Morgannwg

; THE TRIBAL DIVISIONS OF WALES, 273 Garth Bryngi is Dewi's honourable hill, CHAP. And Trallwng Cynfyn above the meadows VIII. Llanfaes the lofty—no breath of war shall touch it, No host shall disturb the churchmen of Llywel.^si It may not be amiss to recall the fact that these posses- sions of St. David's brought here in the twelfth century, to re- side at Llandduw as Archdeacon of Brecon, a scholar of Penfro who did much to preserve for future ages the traditions of his adopted country. Giraldus will not admit the claim of any region in Wales to rival his beloved Dyfed, but he is nevertheless hearty in his commendation of the sheltered vales, the teeming rivers and the well-stocked pastures of Brycheiniog.^^^ IV. The Cantrefs of Morgannwg. The well-sunned plains which, from the mouth of the Tawe to that of the Wye, skirt the northern shore of the Bristol Channel enjoy a mild and genial climate and have from the earliest times been the seat of important settlements. Roman civilisation gained a firm foothold in the district, as may be seen from its remains at Cardiff, Caerleon and Caerwent. Monastic centres of the first rank were established here, at Llanilltud, Llancarfan and Llandaff, during the age of early Christian en- thusiasm. Politically, too, the region stood apart from the rest of South Wales, in virtue, it may be, of the strength of the old Silurian traditions, and it maintained, through many vicissitudes, its independence under its own princes until the eve of the Norman Conquest. -

'IARRIAGES Introduction This Volume of 'Stray' Marriages Is Published with the Hope That It Will Prove

S T R A Y S Volume One: !'IARRIAGES Introduction This volume of 'stray' marriages is published with the hope that it will prove of some value as an additional source for the familv historian. For economic reasons, the 9rooms' names only are listed. Often people married many miles from their own parishes and sometimes also away from the parish of the spouse. Tracking down such a 'stray marriage' can involve fruitless and dishearteninq searches and may halt progress for many years. - Included here are 'strays', who were married in another parish within the county of Powys, or in another county. There are also a few non-Powys 'strays' from adjoining counties, particularly some which may be connected with Powys families. For those researchers puzzled and confused by the thought of dealing with patronymics, when looking for their Welsh ancestors, a few are to be found here and are ' indicated by an asterisk. A simple study of these few examples may help in a search for others, although it must be said, that this is not so easy when the father's name is not given. I would like to thank all those members who have helped in anyway with the compilation of this booklet. A second collection is already in progress; please· send any contributions to me. Doreen Carver Powys Strays Co-ordinator January 1984 WAL ES POWYS FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY 'STRAYS' M A R R I A G E S - 16.7.1757 JOHN ANGEL , bach.of Towyn,Merioneth = JANE EVANS, Former anrl r·r"~"nt 1.:ount les spin. -

Bwlch Circular (Via Mynydd Troed and Lllangorse Lake) Bwlch Circular (Via Pen Tir and Cefn Moel)

Bwlch Circular (via Mynydd Troed and Lllangorse Lake) Bwlch Circular (via Pen Tir and Cefn Moel) 1st walk check 2nd walk check 3rd walk check 1st walk check 2nd walk check 3rd walk check 05th May 2018 09th April 2019 Current status Document last updated Saturday, 25th July 2020 This document and information herein are copyrighted to Saturday Walkers’ Club. If you are interested in printing or displaying any of this material, Saturday Walkers’ Club grants permission to use, copy, and distribute this document delivered from this World Wide Web server with the following conditions: • The document will not be edited or abridged, and the material will be produced exactly as it appears. Modification of the material or use of it for any other purpose is a violation of our copyright and other proprietary rights. • Reproduction of this document is for free distribution and will not be sold. • This permission is granted for a one-time distribution. • All copies, links, or pages of the documents must carry the following copyright notice and this permission notice: Saturday Walkers’ Club, Copyright © 2018-2020, used with permission. All rights reserved. www.walkingclub.org.uk This walk has been checked as noted above, however the publisher cannot accept responsibility for any problems encountered by readers. Bwlch Circular (via Mynydd Troed and Lllangorse Lake) Start & Finish: Bwlch (All Saints Church/New Inn) Bus Stop. Bwlch (All Saints Church/New Inn) Bus Stop, map reference SO 148 220, is 219 km west northwest of Charing Cross, 223m above sea level and in Powys, Wales. Length: 21.6 km (13.4 mi), of which 5.5 km (3.4 mi) are on tarmac or concrete. -

The Great Houses & Estates of Brecknockshire

BRECKNOCK HISTORY FESTIVAL SEPTEMBER & OCTOBER 2017 The Great Houses & Estates of Brecknockshire A range of events across the historic county of Breconshire organised by members of the Brecknock History Forum. Events are being held at the following locations: Brecon Hay on Wye Llandew Llangynidr Llanhamlach Penpont Treholford Brecknock History Forum An informal gathering of groups interested in local and family history across Breconshire. For more information please contact Elaine Starling (01874 711484 or [email protected] Some events are part of OPEN DOORS which celebrates the architecture and heritage of Wales. For a full list of the events being organised for OPEN DOORS across the whole of Wales in September please see the Cadw website. Cover Illustration: Robert Johnson, Survey of the manors of Crickhowell and Tretower, 1587 (National Library of Wales, Badminton Estate Maps, Volume 3, f. 68v) This brochure is kindly sponsored by the Usk Valley Trust ‘JUSTICE AND JOY’ BRECONSHIRE ESTATES FROM THE PERSPECTIVES OF LANDLORD AND TENANT Saturday, 9 September 2017 9.30 am - 4.00 pm The Stables Conference Centre, Penpont, Brecon, LD3 8EU Cost: £10 (£8 Brecknock Society Members) The title of the conference comes from the statement by a 19th Century tenant that paying the rent was an act of justice but securing the freehold was an act of joy. No doubt landlords also have their experiences of justice and joy! Refreshments are not included but tea and coffee can be purchased and a light lunch (cost around £8) will also be available. Please let us know when registering (or by 4 September) if you require lunch. -

The Newsletter of the Federation of Museums & Art Galleries Of

The newsletter of the Federation of Museums & Art Galleries of Wales April 2011 The 2010 Federation AGM, Llanberis In November each year the Federation holds its AGM in a prominent museum or gallery and alternates between North & South Wales. In 2010 the AGM was hosted by the National Slate Museum in Llanberis and the keynote speaker was the new Director General of Amgueddfa Cymru, David Anderson. The event took place in the museum’s Padarn Room, one of two available conference / education rooms. The Federation President, Rachael Rogers (Monmouthshire Museums Service) presented the Federation’s Annual Report for 2009/10 and the The Padarn Room, National Slate Honorary Treasurer, Susan Dalloe (Denbighshire Federation President, Rachael Rogers and keynote speaker, Museum, Llanvberis Director-General of NMW / AC, David Anderson, at the AGM Heritage Service) presented the annual accounts. Following election of Committee Members and other business, David Anderson then gave his talk to the Members. Having only been in his current post as Director General of Amgueddfa Cymru for six weeks, Mr Anderson not only talked of his career and museum experiences that led to his appointment but also asked the Federation Members for their contributions on the Welsh museum and gallery sector and relationships between the differing museums and the National Museum Wales. Following a delicious lunch served in the museum café, the afternoon was spent in a series of workshops with all Members contributing ideas for the Federation’s forthcoming Advocacy strategy and Members toolkit. The Advocacy issue is very important to the Federation especially in the current economic climate and so, particularly if you were unable to attend the AGM, the following article is to encourage your contribution: How Can You Develop an Advocacy Strategy? The Federation is well on its way to finalising an advocacy strategy for museums in Wales.