Kampala, Uganda Casenote

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vote:781 Kira Municipal Council Quarter1

Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2017/18 Vote:781 Kira Municipal Council Quarter1 Terms and Conditions I hereby submit Quarter 1 performance progress report. This is in accordance with Paragraph 8 of the letter appointing me as an Accounting Officer for Vote:781 Kira Municipal Council for FY 2017/18. I confirm that the information provided in this report represents the actual performance achieved by the Local Government for the period under review. Name and Signature: Accounting Officer, Kira Municipal Council Date: 27/08/2019 cc. The LCV Chairperson (District) / The Mayor (Municipality) 1 Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2017/18 Vote:781 Kira Municipal Council Quarter1 Summary: Overview of Revenues and Expenditures Overall Revenue Performance Ushs Thousands Approved Budget Cumulative Receipts % of Budget Received Locally Raised Revenues 7,511,400 1,237,037 16% Discretionary Government Transfers 2,214,269 570,758 26% Conditional Government Transfers 4,546,144 1,390,439 31% Other Government Transfers 0 308,889 0% Donor Funding 0 0 0% Total Revenues shares 14,271,813 3,507,123 25% Overall Expenditure Performance by Workplan Ushs Thousands Approved Cumulative Cumulative % Budget % Budget % Releases Budget Releases Expenditure Released Spent Spent Planning 298,531 40,580 12,950 14% 4% 32% Internal Audit 110,435 15,608 10,074 14% 9% 65% Administration 1,423,810 356,949 150,213 25% 11% 42% Finance 1,737,355 147,433 58,738 8% 3% 40% Statutory Bodies 1,105,035 225,198 222,244 20% 20% 99% Production and Marketing -

UGANDA BUSINESS IMPACT SURVE¥ 2020 Impact of COVID-19 on Formal Sector Small and Mediu Enterprises

m_,," mm CIDlll Unlocking Public and Private Finance for the Poor UGANDA BUSINESS IMPACT SURVE¥ 2020 Impact of COVID-19 on formal sector small and mediu enterprises l anda Revenue Authority •EUROPEAN UNION UGANDA BUSINESS IMPACT SURVEY 2020 Contents ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................................................. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................................................................................................................................. iv EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................. v BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................................ 1 Business in the time of COVID-19 ............................................................................................................ 1 Uganda formal SME sector ........................................................................................................................ 3 SURVEY INFORMATION ................................................................................................................................ 5 Companies by sector of economic activity ........................................................................................... 5 Companies by size ..................................................................................................................................... -

S5 Cut Off May Raise

SATURDAY VISION 10 February 1, 2020 UCE Vision ranking explained Senior Five cut-off points (2019) SCHOOL Boys SCHOOL Boys BY VISION REPORTER their students in division one. Girls Fees (Sh) Girls Fees (Sh) The other, but with a low number of St. Mary’s SS Kitende 10 12 1,200,000 Kinyasano Girls HS 49 520,000 The Saturday Vision ranking considered candidates and removed from the ranking Uganda Martyrs’ SS Namugongo 10 12 1,130,000 St. Bridget Girls High Sch 50 620,000 the average aggregate score to rank was Lubiri Secondary School, Annex. It Kings’ Coll. Budo 10 12 1,200,000 St Mary’s Girls SS Madera Soroti 50 595,200 the schools. Saturday Vision also also had 100% of its candidates passing Light Academy SS 12 1,200,000 Soroti SS 41 53 UPOLET eliminated all schools which had in division one. Namilyango Coll. 14 1,160,000 Nsambya SS 42 42 750,000 the number of candidates below 20 There are other 20 schools, in the entire London Coll. of St. Lawrence 14 16 1,300,000 Gulu Central HS 42 51 724,000 students in the national ranking. nation, which got 90% of their students in The Academy of St. Lawrence 14 16 650,000 Vurra Secondary School 42 52 275,000 A total of about 190 schools were division one. removed from the ranking on this Naalya Sec Sch, Namugongo 15 15 1,000,000 Lango Coll. 42 500,000 basis. nTRADITIONAL, PRIVATE Seeta High (Green Campus) 15 15 1,200,000 Mpanga SS-Kabarole 43 51 UPOLET This is because there were schools with SCHOOLS TOP DISTRICT RANKING Seeta High (Mbalala) 15 15 1,200,000 Gulu SS 43 53 221,000 smaller sizes, as small as five candidates, Traditional schools and usual private top Seeta High (Mukono) 15 15 1,200,000 Lango Coll., S.S 43 like Namusiisi High School in Kaliro. -

LETSHEGO-Annual-Report-2016.Pdf

INTEGRATED ANNUAL REPORT 2016 AbOUT This REPORT Letshego Holdings Limited’s Directors are pleased to present the Integrated Annual Report for 2016. This describes our strategic intent to be Africa’s leading inclusive finance group, as well as our commitment to sustainable value creation for all our stakeholders. Our Integrated Annual Report aims and challenges that are likely to impact to provide a balanced, concise, and delivery of our strategic intent and transparent commentary on our strategy, ability to create value in the short, performance, operations, governance, and medium and long-term. reporting progress. It has been developed in accordance with Botswana Stock The material issues presented in Exchange (BSE) Listing Requirements as the report were identified through well as King III, GRI, and IIRC reporting a stakeholder review process. guidelines. This included formal and informal interviews with investors, sector The cenTral The requirements of the King IV guidelines analysts, Executive and Non- are being assessed and we will address Executive Letshego team members, Theme of The our implementation of these in our 2017 as well as selected Letshego reporT is Integrated Annual Report. customers. sUstaiNAbLE While directed primarily at shareholders A note on diScloSureS vALUE creatiON and providers of capital, this report We are prepared to state what we do and we offer should prove of interest to all our other not disclose, namely granular data on stakeholders, including our Letshego yields and margins as well as on staff an inTegraTed team, customers, strategic partners, remuneration as we deem this to be accounT of our Governments and Regulators, as well as competitively sensitive information the communities in which we operate. -

View/Download

Research Article Food Science & Nutrition Research Risk Factors to Persistent Dysentery among Children under the Age of Five in Rural Sub-Saharan Africa; the Case of Kumi, Eastern Uganda Peter Kirabira1*, David Omondi Okeyo2, and John C. Ssempebwa3 1MD, MPH; Clarke International University, Kampala, Uganda. *Correspondence: 2PhD; School of Public Health, Department of Nutrition and Peter Kirabira, Clarke International University, P.O Box 7782, Health, Maseno University, Maseno Township, Kenya. Kampala, Uganda, Tel: +256 772 627 554; E-mail: drpkirabs@ gmail.com; [email protected]. 3MD, MPH, PhD; Disease Control and Environmental Health Department, School of Public Health, College of Health Sciences, Received: 02 July 2018; Accepted: 13 August 2018 Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda. Citation: Peter Kirabira, David Omondi Okeyo, John C Ssempebwa. Risk Factors to Persistent Dysentery among Children under the Age of Five in Rural Sub-Saharan Africa; the Case of Kumi, Eastern Uganda. Food Sci Nutr Res. 2018; 1(1): 1-6. ABSTRACT Introduction: Dysentery, otherwise called bloody diarrhoea, is a problem of Public Health importance globally, contributing 54% of the cases of childhood diarrhoeal diseases in Kumi district, Uganda. We set out to assess the risk factors associated with the persistently high prevalence of childhood dysentery in Kumi district. Methods: We conducted an analytical matched case-control study, with the under five child as the study unit. We collected quantitative data from the mothers or caretakers of the under five children using semi-structured questionnaires and checklists and qualitative data using Key informer interview guides. Quantitative data was analysed using SPSS while qualitative data was analysed manually. -

Prof. JWF Muwanga-Zake. Phd CV

Covering Letter and Curriculum Vitae for Associate Professor Johnnie Wycliffe Frank Muwanga-Zake Learning Technologist, Educator and Scientist with experience in Higher Education, Research and NGO institutions. Qualifications: B.Sc. (Hons) (Makerere); B.Ed., M.Sc., M.Ed. (Rhodes); PhD (Digital Media in Education, Natal); P.G.C.E. (NUL); P.G.D.E (ICT in Ed.) (Rhodes). To complete at the University of New England, Australia towards the Graduate Certificate in Higher Education. Current Position: Professor and Vice-Chancellor, Uganda Technology and Management University, Kampala. Contact: Emails: [email protected]; [email protected] . Copy to [email protected]. Mobile phone: +256788485749. A. Main Skills and Work Experiences A1. Leadership, administration and management experience (Close to 40 years) 1. Vice-Chancellor, , Uganda Technology and Management – October 2020 - Current. 2. Deputy Vice Chancellor, Uganda Technology and Management – January 2020 – October 2020. 3. Dean, School of Computing and Engineering, Uganda Technology and Management University, Kampala. 4. Associate Chief Editor, International Journal of Technology & Management, Uganda - Current. 5. Initiator and Project Advisor, Electronic Distance Learning (eDL), Cavendish University, Kampala. 6. Team Member of the World Bank project of African Centre of Excellence – Uganda Martyrs University- Current. 7. Dean, Faculty of Science and Technology, Cavendish University, Kampala. 8. Head of the IT Department and Senior Lecturer, School of Computing and Information Technology, Kampala International University. 9. Head, ICT Department, Uganda Martyrs University, Uganda. 10. Head, Learning Technology Forum, University of Greenwich, London. 11. Chairperson, Staff and Curriculum Development, University of Greenwich. 12. Head Coach, Armidale Football Club, Armidale, New South Wales, Australia. -

Croc's 07.Qxd

Croc’s 07.qxd 7/6/2011 5:44 PM Page 2 CLASSIFIED ADVERTS NEW VISION, Thursday, July 7, 2011 29 PROPERTIES KONSULT (U) LTD HIGH POINT JOB SCAN P.O. BOX 71, KAMPALA PROPERTY LTD Sale RONAR CHAMBERS Vacancies NAMIREMBE / BAKULI RD. GOOD NEWS!!!!! (Next to TOTAL Petrol Station) MODERN MAIDS LTD. FOR SALE CALL: 0712 252 605, LAND FOR SALE 0772 850 763, 0312 513444 Entebbe road kitende for sale 2km - Housemaids from main road 20dec with water and - Shamba Boys DEALS OF THE WEEK power at 18m 0772-368798 PLOTS FOR SALE Seguku katale plot for sale 50x100ft at Kakiri - several plots 300mtrs off tax road 12m 50ft x100ft - 3m Seguku katale opp. prayer mt. 1 acre WHOLESALE BUSINESS Mukono- several plots - 4m for sale 2km from main road with lake WANTS: Gayaza - two plots @ 5m view at 200m Bujuuko/Mityana rd 1. Receptionists Naguru hill plot for sale 70 dec at 2. Attendants 100ft x 50ft-3.5m 650,000 dollar 100ft x 100ft - 6m 3. Packers 5 bedroom Wakiso District Kasanjje 30 acres @ at 10m Dealers in Gayaza/Bugema University -near tarmac - 4. Turnboys Headquarters. UGX 160M 800mtrs,with ready Titles Zilobwe Gayaza road 20 acre @ at 100ft x 50ft-5m 4.5m 0775295011 Japanese vehicles. 0701526528 100ft x 100ft-9m Buziga plot for sale1.5acre near King Maya Hill ready titles - Oyo's Palace 500m 100ft x 50ft - 5m Naguru plot for sale 80dec 550,000 LAND - NAMANVE Matuga/Kungu - several plots - 5m dollar 0703-925277 Matuga - power & water on site (50x100)ft - Nakawuka 20 acres for sale near main 7.5m road with water and power at 18m each Gayaza/Namugongo - Prime Estate - 100ft FOR SALE x 50 ft - 7.5m Gayaza road Busiika 35 acres for sale Kayunga/Senge - several plots - 7.5m good for farming at 5m per acre. -

List of URA Service Offices Callcenter Toll Free Line: 0800117000 Email: [email protected] Facebook: @Urapage Twitter: @Urauganda

List of URA Service Offices Callcenter Toll free line: 0800117000 Email: [email protected] Facebook: @URApage Twitter: @URAuganda CENTRAL REGION ( Kampala, Wakiso, Entebbe, Mukono) s/n Station Location Tax Heads URA Head URA Tower , plot M 193/4 Nakawa Industrial Ara, 1 Domestic Taxes/Customs Office P.O. Box 7279, Kampala 2 Katwe Branch Finance Trust Bank, Plot No 115 & 121. Domestic Taxes 3 Bwaise Branch Diamond Trust Bank,Bombo Road Domestic Taxes 4 William Street Post Bank, Plot 68/70 Domestic Taxes Nakivubo 5 Diamond Trust Bank,Ham Shopping Domestic Taxes Branch United Bank of Africa- Aponye Hotel Building Plot 6 William Street Domestic Taxes 17 7 Kampala Road Diamond Trust Building opposite Cham Towers Domestic Taxes 8 Mukono Mukono T.C Domestic Taxes 9 Entebbe Entebbe Kitooro Domestic Taxes 10 Entebbe Entebbe Arrivals section, Airport Customs Nansana T.C, Katonda ya bigera House Block 203 11 Nansana Domestic Taxes Nansana Hoima road Plot 125; Next to new police station 12 Natete Domestic Taxes Natete Birus Mall Plot 1667; KyaliwajalaNamugongoKira Road - 13 Kyaliwajala Domestic Taxes Martyrs Mall. NORTHERN REGION ( East Nile and West Nile) s/n Station Location Tax Heads 1 Vurra Vurra (UG/DRC-Border) Customs 2 Pakwach Pakwach TC Customs 3 Goli Goli (UG/DRC- Border) Customs 4 Padea Padea (UG/DRC- Border) Customs 5 Lia Lia (UG/DRC - Border) Customs 6 Oraba Oraba (UG/S Sudan-Border) Customs 7 Afogi Afogi (UG/S Sudan – Border) Customs 8 Elegu Elegu (UG/S Sudan – Border) Customs 9 Madi-opei Kitgum S/Sudan - Border Customs 10 Kamdini Corner -

Buwate Sports Academy

Buwate Sports Academy Date: Prepared by: October 31, 2018 Naku Charles Lwanga I. Demographic Information 1. City & Province: Buwate, Uganda 2. Organization: Real Medicine Foundation Uganda (www.realmedicinefoundation.org) Mother Teresa Children’s Foundation (www.mtcf-uk.org/) 3. Project Title: Buwate Sports Academy 4. Reporting Period: July 1, 2018 – September 30, 2018 5. Project Location (region & city/town/village): Buwate Village, Kira Town Council, Wakiso District, Kampala, Uganda 6. Target Population: The children and population of Buwate II. Project Information 7. Project Goal: Develop the youth advancement and economic components of our humanitarian work through games, sports training, vocational training, and other educational opportunities. 8. Project Objectives: • Provide funding to assist the operations and growth of Buwate Sports Academy. • Provide funding to allow children from surrounding slums to attend school. • Provide funding for vocational training opportunities, etc. 9. Summary of RMF/MTCF-sponsored activities carried out during the reporting period under each project objective (note any changes from original plans): • School fees were paid for 85 children in Buwate Sports Academy, with funds from RMF. • Buwate Sports Academy organized and held holiday sports programs for the academy children, and welcomed children back to school with serious training for the categories of under-3, under-9, under-11, under-13, and under-16. • Buwate Sports Academy participated in the under-16 category in the Airtel Rising Stars national tournament, held at the Villa Park Nsambya sports grounds in Kampala. Buwate children won with a score of 2-0 against Nsambya Soccer Academy, thus making it to the district tournament level. -

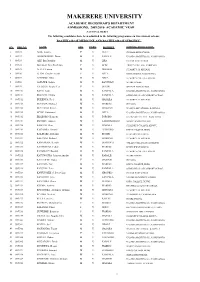

Makerere University

MAKERERE UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC REGISTRAR'S DEPARTMENT ADMISSIONS, 2009/2010 ACADEMIC YEAR NATIONAL MERIT The following candidates have been admitted to the following programme on Government scheme: BACHELOR OF MEDICINE AND BACHELOR OF SURGERY S/N REG NO NAME SEX C'TRY DISTRICT SCHOOL/ INSTITUTION 1 09/U/1 AGIK Sandra F U GULU GAYAZA HIGH SCHOOL 2 09/U/2 AHIMIBISIBWE Davis M U KABALE UGANDA MARTYRS S.S., NAMUGONGO 3 09/U/3 AKII Bua Douglas M U LIRA HILTON HIGH SCHOOL 4 09/U/4 AKULLO Pamella Winnie F U APAC TRINITY COLLEGE, NABBINGO 5 09/U/5 ALELE Franco M U DOKOLO ST MARY'S SS KITENDE 6 09/U/6 ALENI Caroline Acidri F U ARUA MT.ST.MARY'S, NAMAGUNGA 7 09/U/7 AMANDU Allan M U ARUA ST MARY'S COLLEGE, KISUBI 8 09/U/8 ASIIMWE Joshua M U KANUNGU NTARE SCHOOL 9 09/U/9 AYAZIKA Kirabo Tess F U BUGIRI GAYAZA HIGH SCHOOL 10 09/U/10 BAYO Louis M U KAMPALA UGANDA MARTYRS S.S., NAMUGONGO 11 09/U/11 BUKAMA Martin M U KAMPALA OLD KAMPALA SECONDARY SCHOOL 12 09/U/12 BUKENYA Fred M U MASAKA ST MARY'S SS KITENDE 13 09/U/13 BUYINZA Michael M U WAKISO DIPLOMA 14 09/U/14 BUYUNGO Steven M U MUKONO NAALYA SEC. SCHOOL ,KAMPALA 15 09/U/15 ECONI Emmanuel M U ARUA UGANDA MARTYRS S.S., NAMUGONGO 16 09/U/16 EKAKORO Kenneth M U TORORO KATIKAMU SEC. SCH., WOBULENZI 17 09/U/17 EMYEDU Andrew M U KABERAMAIDO NAMILYANGO COLLEGE 18 09/U/18 KABUGO Deus M U MASAKA ST HENRY'S COLLEGE, KITOVU 19 09/U/19 KAGAMBA Samuel M U LUWEERO KING'S COLLEGE, BUDO 20 09/U/20 KALINAKI Abubakar M U BUGIRI KAWEMPE MUSLIM SS 21 09/U/21 KALUNGI Richard M U MUKONO ST MARY'S SS KITENDE 22 09/U/22 KANANURA Keneth M U BUSHENYI VALLEY COLLEGE SS, BUSHENYI 23 09/U/23 KATEREGGA Fahad M U WAKISO KAWEMPE MUSLIM SS 24 09/U/24 KATSIGAZI Ronald M U KAMPALA ST MARY'S COLLEGE, KISUBI 25 09/U/25 KATUNGUKA Johnson Sunday M U KABALE NTARE SCHOOL 26 09/U/26 KATUSIIME Hawa F U MASINDI DIPLOMA 27 09/U/27 KAVUMA Paul M U WAKISO KING'S COLLEGE, BUDO 28 09/U/28 KAVUMA Peter M U KAMPALA OLD KAMPALA SECONDARY SCHOOL 29 09/U/29 KAWUNGEZI S. -

Effectiveness of Distributing HIV Self-Test Kits Through MSM Peer Networks in Uganda

Effectiveness of distributing HIV self-test kits through MSM peer networks in Uganda CROI 2019 Stephen Okoboi1, 2 Oucul Lazarus3, Barbara Castelnuovo1, Collins Agaba3, Mastula Nanfuka3, Andrew Kambugu1 Rachel King4,5 POSTER P-S3 0934 1. Infectious Diseases institute, 2.Clarke International University; 3.The AIDS Support Organization (TASO) ; 4.University of California, San Francisco; Global Health; 5.School of Public Health, Makerere University. Background Results Conclusions/Recommendation • Men who have sex with men (MSM) continue to be •MSM peers distributed a total of 150 HIVST kits to • Our pilot findings suggest that distributing disproportionately impacted globally by the HIV epidemic and MSM participants. HIVST through MSM peer-networks is are also highly stigmatized in Uganda. feasible, effective and a promising •A total of 10 participants were diagnosed with HIV strategy to increase uptake of HIV testing • Peer-driven HIV testing strategies can be effective in infection during the 3 months of kits distribution. and reduce undiagnosed infections identifying undiagnosed infections among high risk among MSM in Uganda populations •This was higher than 4/147 (2.7%) observed in the TASO program Jan-March 2018 (P=0.02). • Based on the pilot results, additional • We examined peer HIV oral fluid self-test kits (HIVST) studies to determine the large-scale network distribution effectiveness in identifying undiagnosed •All diagnosed HIV participants disclosed their test effectiveness of this strategy to overcome HIV infection among MSM in The AIDS Support Organization results to their peers, were confirmed HIV positive the barriers and increase HIV testing (TASO). at a health facility, and initiated on ART. -

36 NEW VISION, Tuesday, May 5, 2015 CLASSIFIED ADVERTS

36 NEW VISION, Tuesday, May 5, 2015 CLASSIFIED ADVERTS PRIVATE MAILOUGAND A ESTATES UGANDA “Your Choice is Our Priority” Tel: 0772 966690, For Genuine 0752966690, 0702000054 Land Titles ** Since 1998 Sema Properties Ltd Tested & Reliable Housing Organised Housing for all 1. NAMUGONGO NSASA Real Estates Ltd ESTATE Well planned plots with Mailo land Millennium Estates via Akright City within good Easter offer, titles at hand. Developers Ltd; "...We build the Nation..." developed neighbourhood celebrate the season MortgageX-MAS OFFER Finance 1. GAYAZA KIGYABIJJO KIRA Well planned Plots with water & power on site with a genuine and Mailoland Titles EBENEZER REAL 80 plots - 50ftx100ft 20m MorrtgageAvailable Finance available TOWN COUNCIL 9.5 Million 2. NAMUGONGO ESTATE Cash and 10 Million Instalments well planned titled 1. BUSIIKA TOWN estates LTD Well planned plots with ready after Protestant shrine with Discount from 200m - 175m for 2. MUKONO MBALALA land 50x100 ft - 4.8m Kampala City view. Power & Jinja High Way land titles easily accessible. complete house and 100x100 ft - 9.6m water on site. 150 plots, 50 x 100 ft - 9m (Cash) Best planned and organized 2. BOMBO TOWN COUNCIL 1. SSEGUKU HILLS VIEW 50ft x 100ft. Shs 23m/=@ 120m - 89m for shell house 50 x 100 ft - 10m (Instalments) Estates with Mailo land titles 50x100 ft - 3.5m ESTATE 3. KIRA – BULINDO ESTATE, 3. KISAMULA MODERN ESTATE And easily accessed from the 100x100 ft - 7m Near tarmac suitable for Home with well-developed PHASE 11 neighborhood, 50 plots, 50ft x main roads 3. KASANJJE GREATER and Rental Apartments in a 100ft Shs 20m/= 50 x 100 ft - 8m (Cash) ENTEBBE II highly develobed neighbourhood 4.