Compulsive Beauty / Hal Foster, P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roger Caillois, Games of Chance and the Superstar Roger Caillois, Games of Chance and the Superstar

Roger Caillois, Games of Chance and the Superstar Roger Caillois, Games of Chance and the Superstar Loek Groot Superstars are not by accident a conspicuous phenomenon in our culture, but inherently belong to a meritocratic society with mass media, free enterprise, and competition. To make this contention plausible I will use Caillois’s book, Man, Play and Games,1 to compare the mechanisms underlying the superstar phenomenon with a special kind of game, as set out by Caillois. As far as I know, Caillois’s book is not quoted in the literature dealing with income distribution theories, although the comparison with play and games is, for limited purposes, interesting. In play and games we find almost all elements which play a role in theories of just income distribution: equality of opportunity, chance, talent, competition and skill, reward, entitlement, winners and losers, etc. These are not chance similarities, for “. games are largely dependent upon the cultures in which they are practised. They affect their preferences, prolong their customs, and reflect their beliefs . One ...can . posit a truly reciprocal relationship between a society and the games it likes to play”.2 Moreover, as we will see, superstars combine the four basic characteristics of play that make their activities a special kind of play. Play or work Johan Huizinga,3 cited by Caillois, considers play as an activity which is not serious (that is, standing outside ordinary life), with no material interest and where no profit can be gained. Caillois disputes Huizinga’s belief that in games no material interests are involved. He sees this belief as a result of Huizinga’s restriction of his analysis to competitive games, and the consequent omission of games of chance. -

Inserting Hans Bellmer's the Doll Into the History of Pornography

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2020 Softcore Surrealism: Inserting Hans Bellmer's The Doll into the History of Pornography Alexandra M. Varga Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses Recommended Citation Varga, Alexandra M., "Softcore Surrealism: Inserting Hans Bellmer's The Doll into the History of Pornography" (2020). Scripps Senior Theses. 1566. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/1566 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 SOFTCORE SURREALISM: INSERTING HANS BELLMER’S THE DOLL INTO THE HISTORY OF PORNOGRAPHY, 2020 By ALEXANDRA M. VARGA SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR ARTS FIRST READER: PROFESSOR MACNAUGHTON, SCRIPPS COLLEGE SECOND READER: PROFESSOR NAKAUE, SCRIPPS COLLEGE MAY 4TH 2020 2 Contents Acknowledgments. 3 Introduction: Finding The Doll. 4 Critical Reception: Who Has Explored The Doll?. 10 Chapter 1: Construction of the Doll and Creation of the Book. 22 Chapter 2: Publication in Germany and France. 37 Conclusion: Too Real For Comfort. 51 Bibliography. 53 Figures: Die Puppe Sequence, 1934. 56 Figures: La Poupée Sequence, 1936. 64 Figures: 19th and 20th Century Pornography. 71 3 Acknowledgments This thesis could not have been written without the support of my thesis readers, Professors Mary MacNaughton and Melanie Nakaue. I would like to thank them for their unwavering support. Their guidance gave me the confidence to pursue such an eccentric topic. -

Postmodernism in Parallax Author(S): Hal Foster Reviewed Work(S): Source: October, Vol

Postmodernism in Parallax Author(s): Hal Foster Reviewed work(s): Source: October, Vol. 63 (Winter, 1993), pp. 3-20 Published by: The MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/778862 . Accessed: 08/10/2012 21:45 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to October. http://www.jstor.org Postmodernismin Parallax* HAL FOSTER Whatever happened to postmodernism?The darling of journalism, it has become the Baby Jane of criticism.Not so long ago the opposite was the case; prominenttheorists on the leftsaw grand thingsin the term.For Jean-Frangois Lyotard postmodernismmarked an end to the masternarratives that had long made modernityseem synonymouswith progress (the march of reason, the accumulation of wealth,the advance of technology,the emancipation of work- ers, and so on), while for FredricJameson postmodernisminvited a new nar- rative,or rather a renewed Marxian critique that mightrelate differentstages of modern culture to differentmodes of capitalistproduction. For me as for many others,postmodernism -

Number 35 July-September

THE BULB NEWSLETTER Number 35 July-September 2001 Amana lives, long live Among! ln the Kew Scientist, Issue 19 (April 2001), Kew's Dr Mike Fay reports on the molecular work that has been carried out on Among. This little tulip«like eastern Asiatic group of Liliaceae that we have long grown and loved as Among (A. edulis, A. latifolla, A. erythroniolde ), but which took a trip into the genus Tulipa, should in fact be treated as a distinct genus. The report notes that "Molecular data have shown this group to be as distinct from Tulipa s.s. [i.e. in the strict sense, excluding Among] as Erythronium, and the three genera should be recognised.” This is good news all round. I need not change the labels on the pots (they still labelled Among), neither will i have to re~|abel all the as Erythronlum species tulips! _ Among edulis is a remarkably persistent little plant. The bulbs of it in the BN garden were acquired in the early 19605 but had been in cultivation well before that, brought back to England by a plant enthusiast participating in the Korean war. Although not as showy as the tulips, they are pleasing little bulbs with starry white flowers striped purplish-brown on the outside. It takes a fair amount of sun to encourage them to open, so in cool temperate gardens where the light intensity is poor in winter and spring, pot cultivation in a glasshouse is the best method of cultivation. With the extra protection and warmth, the flowers will open out almost flat. -

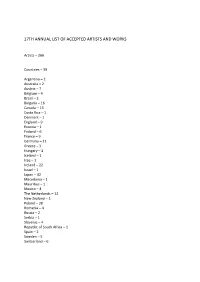

17Th Annual List of Accepted Artists and Works

17TH ANNUAL LIST OF ACCEPTED ARTISTS AND WORKS Artists – 266 Countries – 39 Argentina – 2 Australia – 2 Austria – 7 Belgium – 4 Brazil – 2 Bulgaria – 16 Canada – 13 Costa Rica – 1 Denmark – 1 England – 9 Estonia – 1 Finland – 6 France – 9 Germany – 11 Greece – 3 Hungary – 2 Iceland – 1 Iraq – 1 Ireland – 22 Israel – 1 Japan – 42 Macedonia – 1 Mauritius – 1 Mexico – 4 The Netherlands – 12 New Zealand – 1 Poland – 38 Romania – 4 Russia – 2 Serbia – 1 Slovenia – 4 Republic of South Africa – 1 Spain – 2 Sweden – 5 Switzerland – 6 Taiwan – 2 Thailand – 2 U. S. A. – 22 Venezuela – 1 Featured Artist DIMO KOLIBAROV, Bulgaria Cycle of prints Meetings with Bulgarian Printmaking Artists Presentation of the First Prize Winner of the 16th Mini Print Annual 2017 EVA CHOUNG – FUX, Austria Special Presentation FACULTY OF ARTS MARIA CURIE SKŁODOWSKA UNIVERSITY Lublin, Poland Dr hab. Adam Panek The cycle of prints: 1. Triptych I – A, 2018, Linocut, 15 x 11 cm 2. Triptych I – B, 2018, Linocut, 15 x 9 cm 3. Triptych I – C, 2018, Linocut, 15,5 x 11 cm Dr hab. Alicja Snoch-Pawłowska The cycle of prints: 1. Diffusion 1, 2018, Mixed technique, 12 x 18,5 cm 2. Diffusion 2, 2018, Mixed technique, 12 x 18 cm 3. Diffusion 3, 2018, Mixed technique, 12 x 18,5 cm Dr Amadeusz Popek The cycle of prints: 1. Mirage-Róża, 2018, Serigraphy, 20 x 20 cm 2. Mirage-Pejzaż górski, 2018, Serigraphy, 20 x 20 cm 3. Mirage, 2018, Serigraphy, 20 x 20 cm Mgr Andrzej Mosio The cycle of prints: 1. -

Ranunculaceae) for Asian and North American Taxa

Mosyakin, S.L. 2018. Further new combinations in Anemonastrum (Ranunculaceae) for Asian and North American taxa. Phytoneuron 2018-55: 1–11. Published 13 August 2018. ISSN 2153 733X FURTHER NEW COMBINATIONS IN ANEMONASTRUM (RANUNCULACEAE) FOR ASIAN AND NORTH AMERICAN TAXA SERGEI L. MOSYAKIN M.G. Kholodny Institute of Botany National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine 2 Tereshchenkivska Street Kiev (Kyiv), 01004 Ukraine [email protected] ABSTRACT Following the proposed re-circumscription of genera in the group of Anemone L. and related taxa of Ranunculaceae (Mosyakin 2016, Christenhusz et al. 2018) and based on recent molecular phylogenetic and partly morphological evidence, the genus Anemonastrum Holub is recognized here in an expanded circumscription (including Anemonidium (Spach) Holub, Arsenjevia Starod., Tamuria Starod., and Jurtsevia Á. Löve & D. Löve) covering members of the “Anemone ” clade with x=7, but excluding Hepatica Mill., a genus well outlined morphologically and forming a separate subclade (accepted by Hoot et al. (2012) as Anemone subg. Anemonidium (Spach) Juz. sect. Hepatica (Mill.) Spreng.) within the clade earlier recognized taxonomically as Anemone subg. Anemonidium (sensu Hoot et al. 2012). The following new combinations at the section and subsection ranks are validated: Anemonastrum Holub sect. Keiskea (Tamura) Mosyakin, comb. nov . ( Anemone sect. Keiskea Tamura); Anemonastrum [sect. Keiskea ] subsect. Keiskea (Tamura) Mosyakin, comb. nov .; Anemonastrum [sect. Keiskea ] subsect. Arsenjevia (Starod.) Mosyakin, comb. nov . ( Arsenjevia Starod.); and Anemonastrum [sect. Anemonastrum ] subsect. Himalayicae (Ulbr.) Mosyakin, comb. nov. ( Anemone ser. Himalayicae Ulbr.). The new nomenclatural combination Anemonastrum deltoideum (Hook.) Mosyakin, comb. nov . ( Anemone deltoidea Hook.) is validated for a North American species related to East Asian Anemonastrum keiskeanum (T. -

Action Yes, 1(7): 1-17

http://www.diva-portal.org This is the published version of a paper published in . Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Bäckström, P. (2008) One Earth, Four or Five Words: The Notion of ”Avant-Garde” Problematized Action Yes, 1(7): 1-17 Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:lnu:diva-89603 ACTION YES http://www.actionyes.org/issue7/backstrom/backstrom-printfriendl... s One Earth, Four or Five Words The Notion of 'Avant-Garde' Problematized by Per Bäckström L’art, expression de la Société, exprime, dans son essor le plus élevé, les tendances sociales les plus avancées; il est précurseur et révélateur. Or, pour savoir si l’art remplit dignement son rôle d’initiateur, si l’artiste est bien à l’avant-garde, il est nécessaire de savoir où va l’Humanité, quelle est la destinée de l’Espèce. [---] à côté de l’hymne au bonheur, le chant douloureux et désespéré. […] Étalez d’un pinceau brutal toutes les laideurs, toutes les tortures qui sont au fond de notre société. [1] Gabriel-Désiré Laverdant, 1845 Metaphors grow old, turn into dead metaphors, and finally become clichés. This succession seems to be inevitable – but on the other hand, poets have the power to return old clichés into words with a precise meaning. Accordingly, academic writers, too, need to carry out a similar operation with notions that are worn out by frequent use in everyday language. -

Drawing Surrealism Didactics 10.22.12.Pdf

^ Drawing Surrealism Didactics Drawing Surrealism is the first-ever large-scale exhibition to explore the significance of drawing and works on paper to surrealist innovation. Although launched initially as a literary movement with the publication of André Breton’s Manifesto of Surrealism in 1924, surrealism quickly became a cultural phenomenon in which the visual arts were central to envisioning the world of dreams and the unconscious. Automatic drawings, exquisite corpses, frottage, decalcomania, and collage are just a few of the drawing-based processes invented or reinvented by surrealists as means to tap into the subconscious realm. With surrealism, drawing, long recognized as the medium of exploration and innovation for its use in studies and preparatory sketches, was set free from its associations with other media (painting notably) and valued for its intrinsic qualities of immediacy and spontaneity. This exhibition reveals how drawing, often considered a minor medium, became a predominant mode of expression and innovation that has had long-standing repercussions in the history of art. The inclusion of drawing-based projects by contemporary artists Alexandra Grant, Mark Licari, and Stas Orlovski, conceived specifically for Drawing Surrealism , aspires to elucidate the diverse and enduring vestiges of surrealist drawing. Drawing Surrealism is also the first exhibition to examine the impact of surrealist drawing on a global scale . In addition to works from well-known surrealist artists based in France (André Masson, Max Ernst, Joan Miró, Salvador Dalí, among them), drawings by lesser-known artists from Western Europe, as well as from countries in Eastern Europe and the Americas, Great Britain, and Japan, are included. -

For Peer Review

Games and Culture Introduction. The Other Caillois: the many masks of game studies Journal:For Games Peer and Culture Review Manuscript ID Draft Manuscript Type: Caillois Special Issue Roger Caillois, Game studies, Dissymmetry, Gamification, Keywords: Interdisciplinarity, Mimicry, Ludus, Paidia, Marxism, Agency, Alea, Ilinx The legacy of the rich, stratified work of Roger Caillois, the multi-faceted and complex French scholar and intellectual, seems to have almost solely impinged on game studies through his most popular work, Les Jeux et les Hommes (1957). Translated in English as Man, Play and Games (1961), this is the text which popularized Caillois’ ideas among those who do study and research on games and game cultures today, and which most often Abstract: appears in publications that attempt to historicize and introduce to the study of games––perhaps on a par with Johan Huizinga’s Homo Ludens (1938). The purpose of this paper is to introduce the papers and general purposes of a collected edition that aims to shift the attention of game scholars towards a more nuanced and comprehensive view of Roger Caillois, beyond the textbook interpretations usually received in game studies over the last decade or so. http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/sage/games Page 1 of 16 Games and Culture 1 2 3 4 5 6 Introduction––The Other Caillois: the many masks of game studies 7 8 9 10 11 The legacy of the multi-faceted and complex work of Roger Caillois, the French scholar and 12 intellectual, seems to have almost solely impinged on game studies through his most popular 13 work, Les Jeux et les Hommes (1957). -

G a G O S I a N G a L L E R Y Hiroshi Sugimoto Biography

G A G O S I A N G A L L E R Y Hiroshi Sugimoto Biography Born in 1948, Tokyo. Lives and works in New York. Education: 1972 BFA, Art Center College of Design, Los Angeles. 1966-1970 BA, Saint Paul's University, Tokyo. Solo Exhibitions: 2009 Lightning Fields, Gallery Koyanagi, Tokyo, Japan. Lightning Fields, Fraenkel Gallery San Francisco, CA. 2008 Hiroshi Sugimoto: Seven Days/Seven Nights, Gagosian Gallery, New York. Hiroshi Sugimoto, Museum der Moderne, Salzburg, Austria. Hiroshi Sugimoto, Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin. Hiroshi Sugimoto, Kunstmuseum Luzern, Switzerland. Hiroshi Sugimoto: History of History, The National Museum of Art, Osaka, Japan. Travelled to: 21st century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, Japan. 2007 Leakage of Light, Gallery Koyanagi, Tokyo. Hiroshi Sugimoto, K20 Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, Germany. Travlled to: Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, Villa Manin Centro d’Arte Contemporanea, Udine, Italy. Hiroshi Sugimoto, Villa Manin, Passariano, Italy. Hiroshi Sugimoto: Colors of shadow, Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco, CA. 2006 Hiroshi Sugimoto, Modern Art Museum, Fort Worth, TX. Hiroshi Sugimoto: Colors of Shadow, Sonnabend, New York. Hiroshi Sugimoto: Mathematical Forms, Galerie de l’Aterlier Brancusi, Paris. Hiroshi Sugimoto, Galerie Marian Goodman, Paris. Hiroshi Sugimoto:Joe, Gagosian Gallery, Beverly Hills. Hiroshi Sugimoto: Photographs of Joe, The Pulitzer Foundation for the Arts, St. Louis, MO. Hiroshi Sugimoto, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C. Hiroshi Sugimoto: History of History, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, The Smithsonian, Washington D.C. 2005 Hiroshi Sugimoto: History of History, Japan Society, New York. Hiroshi Sugimoto: Retrospective, Mori Art Museum, Tokyo. (through 2006) Conceptual Forms, Gagosian Gallery, London (Britannia Street) and Sonnabend Gallery, New York. -

1 Introduction the Empire at the End of Decadence the Social, Scientific

1 Introduction The Empire at the End of Decadence The social, scientific and industrial revolutions of the later nineteenth century brought with them a ferment of new artistic visions. An emphasis on scientific determinism and the depiction of reality led to the aesthetic movement known as Naturalism, which allowed the human condition to be presented in detached, objective terms, often with a minimum of moral judgment. This in turn was counterbalanced by more metaphorical modes of expression such as Symbolism, Decadence, and Aestheticism, which flourished in both literature and the visual arts, and tended to exalt subjective individual experience at the expense of straightforward depictions of nature and reality. Dismay at the fast pace of social and technological innovation led many adherents of these less realistic movements to reject faith in the new beginnings proclaimed by the voices of progress, and instead focus in an almost perverse way on the imagery of degeneration, artificiality, and ruin. By the 1890s, the provocative, anti-traditionalist attitudes of those writers and artists who had come to be called Decadents, combined with their often bizarre personal habits, had inspired the name for an age that was fascinated by the contemplation of both sumptuousness and demise: the fin de siècle. These artistic and social visions of degeneration and death derived from a variety of inspirations. The pessimistic philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860), who had envisioned human existence as a miserable round of unsatisfied needs and desires that might only be alleviated by the contemplation of works of art or the annihilation of the self, contributed much to fin-de-siècle consciousness.1 Another significant influence may be found in the numerous writers and artists whose works served to link the themes and imagery of Romanticism 2 with those of Symbolism and the fin-de-siècle evocations of Decadence, such as William Blake, Edgar Allen Poe, Eugène Delacroix, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Charles Baudelaire, and Gustave Flaubert. -

Dalí's Surrea¡¡St Activities and the Model of Scientific Experimentationr

@ Astrid Ruffa, 2005 Dalí's surrea¡¡st activities and the model of scientific experimentationr Astrid Ruffa Abstract This paper aims to explore relationships between Salvador Dalí's practices at the end of the 1920i ånd during the 1930s, and models of scientific experimentation. ln 1928 Dalí took a growing interest in André Breton's automatism and elaborated his first conception of õurrealilm which was based on the model of the scientific observation of nature. Dalí's writings of this period mimicked protocols of botanic or entomological experiments and refonñulated in an original way Bre'ton's surrealist proiect: they simulated the conditions and practices of scientific óbservaiions of nature. Paradoxically, this documentaristic and hyper- were oO¡éctive attitude led to a hyper-subjective and surrealistic description of reality: objects taken out of their context, if,ey were broken up and no longer recognisable' When Dalí his officially entered Breton's group-and conceived the paranoiac-critical method, he focused attention on another scieniific model: Albert Einstein;s notion of space{ime. Dalí appropriated and a concept which defined the inextricable relationship between space{ime and the object which b'ecame, in his view, the mental model of the interaction between interiority and exteriority, invisible and visible, subjectivity and objectivity. Significantly, the Catalan artist almost rewrote one of Einstein's own papers, by pointing out the active dimension of Einstein's space-time and by conferring new meanings on his notion of the space-time curve. I will track down the migrátion of thiã concept from physics to Dalí's surrealist vision by most considering its importancã in writings where the artist uses his method to interpret the varied phðnomena, from the my[n ot Narcissus, to English pre-Raphaelitism and the architecture of Antoni Gaudí.