Inflection in the Ezeagu Dialect of Igbo Language Christian Ezenwa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

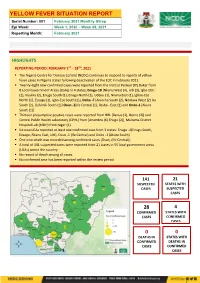

YELLOW FEVER SITUATION REPORT Serial Number: 001 February 2021 Monthly Sitrep Epi Week: Week 1, 2020 – Week 08, 2021 Reporting Month: February 2021

YELLOW FEVER SITUATION REPORT Serial Number: 001 February 2021 Monthly Sitrep Epi Week: Week 1, 2020 – Week 08, 2021 Reporting Month: February 2021 HIGHLIGHTS REPORTING PERIOD: FEBRUARY 1ST – 28TH, 2021 ▪ The Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) continues to respond to reports of yellow fever cases in Nigeria states following deactivation of the EOC in February 2021. ▪ Twenty -eight new confirmed cases were reported from the Institut Pasteur (IP) Dakar from 8 Local Government Areas (LGAs) in 4 states; Enugu-18 [Nkanu West (4), Udi (3), Igbo-Etiti (2), Nsukka (2), Enugu South (1), Enugu North (1), Udenu (1), Nkanu East (1), Igboe-Eze North (1), Ezeagu (1), Igbo-Eze South (1)], Delta -7 [Aniocha South (2), Ndokwa West (2) Ika South (2), Oshimili South (1)] Osun -2[Ife Central (1), Ilesha - East (1) and Ondo-1 [Akure South (1)] ▪ Thirteen presumptive positive cases were reported from NRL [Benue (2), Borno (2)] and Central Public Health Laboratory (CPHL) from [Anambra (6) Enugu (2)], Maitama District Hospital Lab (MDH) from Niger (1) ▪ Six new LGAs reported at least one confirmed case from 3 states: Enugu -4(Enugu South, Ezeagu, Nkanu East, Udi), Osun -1 (Ife Central) and Ondo -1 (Akure South) ▪ One new death was recorded among confirmed cases [Osun, (Ife Central)] ▪ A total of 141 suspected cases were reported from 21 states in 55 local government areas (LGAs) across the country ▪ No record of death among all cases. ▪ No confirmed case has been reported within the review period 141 21 SUSPECTED STATES WITH CASES SUSPECTED CASES 28 4 -

Evaluation of Rural Water Sources and Sustainable Approaches to Rural Water Resources Development in Ezeagu, Enugu, Eastern Nigeria

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2013): 6.14 | Impact Factor (2013): 4.438 Evaluation of Rural Water Sources and Sustainable Approaches to Rural Water Resources Development in Ezeagu, Enugu, Eastern Nigeria Nwagbara, A.O.1, Chijioke, E.O. 2 Faculty of Environmental Sciences, Enugu State University of Science and Technology, Agbani, Enugu, Nigeria Abstract: This study evaluated the water resources in Ezeagu and suggested sustainable approaches to water resources development in this area. Five towns were randomly selected from each of the three geographical zones and their water sources were evaluated. Direct observations, interviews and real time field survey were used to obtain reliable data on the state of water resources in the selected towns in Ezeagu Local Government Area. From the study, only three communities from the selected areas have big rivers that sustain their communities while others are water-stressed and depend on rain water harvesting, unprotected well, tanker-truck. It is obvious that nature has made the distribution of natural resources unequal. Tables 2 and 3 show that only Ozom Mgbagbu Owa, Olo and Umumba Ndiagu are the towns naturally endowed with big rivers that sustain them in Ezeagu Local Government Area. These rivers are the sources of water supply for the commercial water supply tanker drivers. Isigwu Umana, Aguobu Owa, Okpogho, Ihuonyia, Obeleagu Umana and Akama Oghe do not have reliable sources of water supply. Consequently they patronize the commercial tanker drivers. This study is significant as it will help the Local Government Authority in understanding the problems of Ezeagu Local Government Area with respect to availability of adequate and improved water supply. -

Niger Delta Budget Monitoring Group Mapping

CAPACITY BUILDING TRAINING ON COMMUNITY NEEDS ASSESSMENT & SHADOW BUDGETING NIGER DELTA BUDGET MONITORING GROUP MAPPING OF 2016 CAPITAL PROJECTS IN THE 2016 FGN BUDGET FOR ENUGU STATE (Kebetkache Training Group Work on Needs Assessment Working Document) DOCUMENT PREPARED BY NDEBUMOG HEADQUARTERS www.nigerdeltabudget.org ENUGU STATE FEDERAL MINISTRY OF EDUCATION UNIVERSAL BASIC EDUCATION (UBE) COMMISSION S/N PROJECT AMOUNT LGA FED. CONST. SEN. DIST. ZONE STATUS 1 Teaching and Learning 40,000,000 Enugu West South East New Materials in Selected Schools in Enugu West Senatorial District 2 Construction of a Block of 3 15,000,000 Udi Ezeagu/ Udi Enugu West South East New Classroom with VIP Office, Toilets and Furnishing at Community High School, Obioma, Udi LGA, Enugu State Total 55,000,000 FGGC ENUGU S/N PROJECT AMOUNT LGA FED. CONST. SEN. DIST. ZONE STATUS 1 Construction of Road Network 34,264,125 Enugu- North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East New Enugu South 2 Construction of Storey 145,795,243 Enugu-North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East New Building of 18 Classroom, Enugu South Examination Hall, 2 No. Semi Detached Twin Buildings 3 Purchase of 1 Coastal Bus 13,000,000 Enugu-North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East Enugu South 4 Completion of an 8-Room 66,428,132 Enugu-North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East New Storey Building Girls Hostel Enugu South and Construction of a Storey Building of Prep Room and Furnishing 5 Construction of Perimeter 15,002,484 Enugu-North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East New Fencing Enugu South 6 Purchase of one Mercedes 18,656,000 Enugu-North Enugu North/ Enugu East South East New Water Tanker of 11,000 Litres Enugu South Capacity Total 293,145,984 FGGC LEJJA S/N PROJECT AMOUNT LGA FED. -

The Impact of Supervised Agricultural Credit Scheme in Ezeagu Local Government Area of Enugu State, Nigeria

Botany Research International 6 (3): 74-80, 2013 ISSN 2221-3635 © IDOSI Publications, 2013 DOI: 10.5829/idosi.bri.2013.6.3.513 The Impact of Supervised Agricultural Credit Scheme in Ezeagu Local Government Area of Enugu State, Nigeria 12Miriam Mgbakor, Ugwu Jennifer Nkechi and 2G.N. Nenna 1Department of Agricultural Economics, Extension Enugu State University of Science and Technology (ESUT) Enugu, Nigeria 2Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension. Anambra State University, Igbariam Campus Abstract: This study investigated the impact of the Supervised Agricultural Credit Scheme on Small-scale farmers in Ezeagu Local Government Area of Enugu State of Nigeria. Three hundred and fifty farmers were randomly selected from the study area and interviewed by means of structured questionnaires. 300 questionnaires were later found to be analyzable. The findings indicate that the scheme had performed relatively well in the area of study and the repayment rates were high. Four innovations that had reached a high degree of adoption include: improved cassava; the supervised agricultural credit scheme (SACS); fertilizer and improved maize. Appropriate recommendations aimed at improving upon the functionality of the scheme in the study area have been made. Key words: Ezeagu Agricultural credit Small scale farming and Enugu INTRODUCTION Hitherto, shifting cultivation had been rife in some parts of the country. Traditional farming is plagued by The Problem: Agriculture plays a major role in the several constraints such as low capacity tools, very low economic development of many countries. Over 70 levels of production inputs, inadequate storage, percent of Nigeria’s adult population is engaged in the traditional land tenure system and heavy losses from agricultural sector and other related industries. -

New Projects Inserted by Nass

NEW PROJECTS INSERTED BY NASS CODE MDA/PROJECT 2018 Proposed Budget 2018 Approved Budget FEDERAL MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND RURAL SUPPLYFEDERAL AND MINISTRY INSTALLATION OF AGRICULTURE OF LIGHT AND UP COMMUNITYRURAL DEVELOPMENT (ALL-IN- ONE) HQTRS SOLAR 1 ERGP4145301 STREET LIGHTS WITH LITHIUM BATTERY 3000/5000 LUMENS WITH PIR FOR 0 100,000,000 2 ERGP4145302 PROVISIONCONSTRUCTION OF SOLAR AND INSTALLATION POWERED BOREHOLES OF SOLAR IN BORHEOLEOYO EAST HOSPITALFOR KOGI STATEROAD, 0 100,000,000 3 ERGP4145303 OYOCONSTRUCTION STATE OF 1.3KM ROAD, TOYIN SURVEYO B/SHOP, GBONGUDU, AKOBO 0 50,000,000 4 ERGP4145304 IBADAN,CONSTRUCTION OYO STATE OF BAGUDU WAZIRI ROAD (1.5KM) AND EFU MADAMI ROAD 0 50,000,000 5 ERGP4145305 CONSTRUCTION(1.7KM), NIGER STATEAND PROVISION OF BOREHOLES IN IDEATO NORTH/SOUTH 0 100,000,000 6 ERGP445000690 SUPPLYFEDERAL AND CONSTITUENCY, INSTALLATION IMO OF STATE SOLAR STREET LIGHTS IN NNEWI SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 7 ERGP445000691 TOPROVISION THE FOLLOWING OF SOLAR LOCATIONS: STREET LIGHTS ODIKPI IN GARKUWARI,(100M), AMAKOM SABON (100M), GARIN OKOFIAKANURI 0 400,000,000 8 ERGP21500101 SUPPLYNGURU, YOBEAND INSTALLATION STATE (UNDER OF RURAL SOLAR ACCESS STREET MOBILITY LIGHTS INPROJECT NNEWI (RAMP)SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 9 ERGP445000692 TOSUPPLY THE FOLLOWINGAND INSTALLATION LOCATIONS: OF SOLAR AKABO STREET (100M), LIGHTS UHUEBE IN AKOWAVILLAGE, (100M) UTUH 0 500,000,000 10 ERGP445000693 ANDEROSION ARONDIZUOGU CONTROL IN(100M), AMOSO IDEATO - NCHARA NORTH ROAD, LGA, ETITI IMO EDDA, STATE AKIPO SOUTH LGA 0 200,000,000 11 ERGP445000694 -

Gender Roles and Challenges of Small Scale Cashew Nut Processingenterprise in Enugu North, Nigeria

ISSN 2239-978X Journal of Educational and Social Research Vol. 4 No.7 ISSN 2240-0524 MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy November 2014 Gender Roles and Challenges of Small Scale Cashew Nut ProcessingEnterprise in Enugu North, Nigeria I. A. Enwelu* S. T. Ugwu Ayogu C. J. Ogbonna, O. I. Department of Agricultural Extension, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Enugu State, Nigeria Doi:10.5901/jesr.2014.v4n7p74 Abstract Small scale cashew nut processing enterprise is important in meeting the needs of the local processors and strategic in the current transformation agenda of the government. The study examined the gender roles and challenges of small scale cashew nut processing enterprise in Enugu North Senatorial zone of Enugu State. Seventy two small scale cashew nut processors were identified and interviewed to elicit information for the study. The study revealed that youths on the whole were found to be more effective in most of the activities of cashew nut processing namely packaging (M=2.0), grading (M=1.90), sizing (M=1.50 and cleaning (M=1.50). On the other hand, men played more effective role in two processing activities- shelling (M=2.0) and peeling (M=2.0) while women played more effective role only in one activity- roasting/frying (M=1.80). It was found that all the respondents (100.0%) were still using local processing method like open pan roasting. About 19.0% of the respondents processed 3-5kg per day while 12.4%, 2.2% and 1.4% processed 6-8kg, 9-11kg and 12-14kg per day respectively. The challenges of small scale cashew nut processors were chemical burns (M=3.86), damage of kernels by fire through non regulation of heat (M=3.67), high cost of kernels (M=3.57) and excess heat affecting the body. -

Challenges of Participatory Approach to Watershed Management in Rural Communities of Enugu State

Journal of Agricultural Extension Vol. 14 (1), June 2010 Challenges of Participatory Approach to Watershed Management in Rural Communities of Enugu State Enwelu, 1.A*.; Agwu, A.E. and Igbokwe, E.M. Department of Agricultural Extension University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Enugu State. *E-mails: [email protected] Mobile: +2348035090033 Abstract The study highlights the status of existing watersheds management in four rural communities of Enugu State. Both qualitative and quantitative approaches (Rapid Rural Appraisal, focus group discussions, key informant interviews, and semi- structured interview schedules) were used in an interactive manner to collect data for this study from four rural communities in the state. The study revealed that many problems such as fuel wood exploitation, farming activities, animal grazing/hunting, and road/house construction, among others were factors threatening the sustainability of watersheds in Enugu State. The study also showed that many of the communities had rules and regulations guiding the use of watersheds but could not apply the principle of participatory management approach to ensure sustainability of the watersheds. However, the rules and regulations merely emphasized environmental sanitation of the watershed surroundings without ensuring the overall sustainability of the watersheds. The paper concludes with the need for public and private extension services to educate key actors in rural communities on the sustainability of using participatory watershed management approach. Key words: Sustainability, status, rules and regulations. Introduction Generally speaking, water is wrongly recognized as an inexhaustible commodity by people living in areas where there is plenty of it at the moment. According to Pitman (2002) water should be recognized as a scarce natural resource subject to many interdependencies in conveyance and use. -

Patterns and Problems of Domestic Water Supply to Rural Communities in Enugu State, Nigeria

Vol.9(8), pp. 172-184, August 2017 DOI: 10.5897/JAERD2016.0802 Articles Number: F7A3AA765525 Journal of Agricultural Extension and ISSN 2141-2170 Copyright ©2017 Rural Development Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/JAERD Full Length Research Paper Patterns and problems of domestic water supply to rural communities in Enugu State, Nigeria Obeta Michael Chukwuma Hydrology and Water Resources Unit, Department of Geography, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Enugu State, Nigeria. Received 11 July, 2016; Accepted 21 September, 2016 This study investigated the patterns, problems and options for improved domestic water supplies to the rural communities of Enugu State, Nigeria. The purpose of the study was to determine the gap between supply and demand, physical and socio-economic variables that influence the supply situation and suggest options for improved water supply in the area. Data on water use habits were collected from 340 households, in 17 autonomous communities through the use of questionnaire and oral interview. Additional data were collected though field observations, from three FGDs and from relevant records at the offices of the Enugu State Water Corporation. The data were analyzed through the use of inferential and descriptive statistical tools. The results of the study revealed that wide gaps exist between water supply and demand in all the sampled communities. The water schemes developed by governments and NGOs are largely non-functional. The quantities of water demanded and supplied vary widely. The mean household water demand was found to be 13685.5 lpd against the supply 9028.8 lpd, leaving a daily household deficit of 4656.9 lpd. -

260 Candidates for Supplementary Interview.Xlsx

WYEP S/N NUMBER SURNAME FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME GENDER AGE VALUE CHAIN LGA OF RESIDENCE PHONE NUMBER 1 018789 OGBU OGONNA UZOAMAKA FEMALE 38 POULTRY NKANU EAST 08037617217 2 008499 EZE IFEYINWA UKAMAKA FEMALE 31 POULTRY ENUGU SOUTH 08032529902 3 386 ENEZE CHIDINMA MERCY FEMALE 28 POULTRY UDI 8169694935 4 011910 JIKANU MARY FEMALE 23 RICE PRODUCTION UDI 81074093 5 021382 ONAH CHINWE EMMANUELLA FEMALE 37 RICE ENUGU EAST 08063821246 6 013671 MBADAH WILLIAMS CHIDI MALE 40 POULTRY ENUGU EAST 07030913475 7 025225 UGWUAGBA EJIOFOR ALOYSIUS MALE 40 RICE MARKETING IGBO -ETITI 08035830234 8 013783 MBAH EMMANUEL OBINNA MALE 33 CASSAVA ENUGU EAST 08061147946 9 003450 AMADI CHIKAODILI JULIET FEMALE 28 POULTRY IGBO -ETITI 07030389913 10 018582 OGBONNA MARTIN ONYEBUCHI MALE 40 POULTRY IGBO-EZE NORTH 080601433380 11 016412 NWARU KENNETH IKECHUKWU MALE 41 RICE PRODUCTION ANINRI 07069656851 12 010466 IDOGWU AGUSTINA OBIAGELI FEMALE 40 POULTRY ENUGU EAST 07060908371 13 027088 AKPA ULOMA EVERITUS FEMALE 23 POULTRY ANINRI 07032484649 14 027071 UKWUEZE ZACCHAEUS IKEDICHUKWU MALE 34 RICE IGBO EZE SOUTH 08034431401 15 024969 UDEH STEPHEN ONWUMERE MALE OA RICE PRODUCTION ANINRI 08088597059 16 015790 NNONNA LYNDA OBY FEMALE 51 POULTRY ENUGU EAST 08099364911 17 021385 ONAH AMAUCHE KINGSLEY MALE 31 POULTRY PROCESSING UDENU 08141289651 18 008826 EZEILO IZUCHUKWU CHRISTOPHER MALE 26 POULTRY PRODUCTION ENUGU EAST 0810736648 19 008489 EZE CONTANCE EBERE FEMALE 35 POULTRY PRODUCTION IGBO EZE SOUTH 09064248994 20 000955 ANIEKWU CHIBUZOR PETER MALE 26 POULTRY PRODUCTION -

Multivariate Analysis of Ground Water Characteristics of Geological Formations of Enugu State of Nigeria

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 4, ISSUE 08, AUGUST 2015 ISSN 2277-8616 Multivariate Analysis Of Ground Water Characteristics Of Geological Formations Of Enugu State Of Nigeria. Orakwe, LC, Chukwuma, EC Abstract: The chemometric data mining techniques using principal factor analysis (PFA), and hierarchical cluster analysis (CA), was employed to evaluate, and to examine the borehole characteristics of geological formations of Enugu State of Nigeria to determine the latent structure of the borehole characteristics and to classify 9 borehole parameters from 49 locations into borehole groups of similar characteristics. PFA extracted three factors which accounted for a large proportion of the variation in the data (77.305% of the variance). Out of nine parameters examined, the first PFA had the highest number of variables loading on a single factor where four borehole parameters (borehole depth, borehole casing, static water level and dynamic water level) loaded on it with positive coefficient as the most significant parameters responsible for variation in borehole characteristics in the study. The CA employed in this study to identified three clusters. The first cluster delineated stations that characterise Awgu sandstone geological formation, while the second cluster delineated Agbani sandstone geological formation. The third cluster delineated Ajali sandstone formation. The CA grouping of the borehole parameters showed similar trend with PFA hence validating the efficiency of chemometric data mining techniques in grouping of variations in the borehole characteristics in the geological zone of the study area. Keywords: Borehole Characteristics, Multivariate Analysis, Cluster Analysis, Principal Factor Analysis, Geological Formations, Enugu state. ———————————————————— 1. INTRODUCTION desert in the north and the Kalahari desert in the south [2]. -

(Issn: 2504-8694) Dialectal Variations of Oghe

Interdisciplinary Journal of African & Asian Studies, Vol. 1, No. 2, 2016 (ISSN: 2504-8694) DIALECTAL VARIATIONS OF OGHE Christian E. C. Ogwudile Department of Igbo, African & Asian Studies Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka [email protected] +2348037468693 ABSTRACT This work is a descriptive survey on the dialectal variations of Oghe, a dialect of Igbo spoken in Ezeagu local government area of Enugu State, Nigeria. The paper aims to establish the difference between Oghe dialect and standard Igbo and also to find out if Oghe dialect has made any contribution to the development of standard Igbo. This sudy is a Sociolinguistic study that takes a look into dialectal variations of Oghe. Oghe dialect is very distinct and interesting. To establish the level of variation in Oghe dialect, this paper first highlights the introduction which took a cursory look at the observations and views of Igbo linguists on dialect. The method of obtaining data is through structured interview. Related literature to the study were reviewed. The paper paid serious attention to the pronunciations of some lexical items and sentences of Oghe dialect in line with the standard Igbo. The differences in Oghe dialect with the standard Igbo are also established and the paper also identified the factors responsible for the differences. Some findings and suggestions are made where it was suggested that though uniformity creates room for standard, the dialect of Oghe should be encouraged to exist side by side with standard Igbo. Also standard Igbo should be drawn from the dialect of the Igbo speakers. As a result, Oghe dialect should form part of the standard Igbo. -

PRELIMINARY STUDY of AFFIA CAVE, WATERFALL and NATURAL BRIDGE in OKPATU, ENUGU STATE by Okpoko, P.U, Okonkwo, E

PRELIMINARY STUDY OF AFFIA CAVE, WATERFALL AND NATURAL BRIDGE IN OKPATU, ENUGU STATE By Okpoko, P.U, Okonkwo, E. E, and Eyisi, A. P Department of Archaeology and Tourism, University of Nigeria, Nsukka DOI:https://doi.org/10.33281/JTHS20129.2016.5.1&2.4 Abstract Caves and waterfalls abound in most parts of Igboland. They are the rich nature-induced attractions, which when developed will not only bring development, but also revenue to the destinations in which they are located. Enugu State is endowed with natural and cultural tourism resources located across the state, all of which can produce a distinctive tourism industry capable of generating income and raising the living standard of the local people. This study is aimed at bringing to limelight the cave, waterfall and natural bridge in Okpatu, Udi Local Government Area (L.G.A) of Enugu State. The research employed reconnaissance survey, interviews and direct observation to elicit information in the study community. Preliminary findings revealed that the sites have great potentialities, given the scenic attractions, rich heritage resources in the community and their proximity to already existing attractions within the visitor domain (including the standing furnaces in Ibite-Okpatu and the Awhum Monastery with a cave). It is proposed that the sites be developed so as to ensure improved visitation to the area. Local participation should also be encouraged to ensure sustainability of such development. Keywords: Cave, Waterfall, Tourism, Potentials, Development INTRODUCTION Many natural and cultural sites which are veritable sources of income and capable of raising the standard of living of the various communities where they are found in different parts of the world, are being destroyed in Nigeria due to human activities, including farming, road construction, with little or no consideration on the adverse effect of such activities on our heritage.