The “Tragic” Father of Gods and Men

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Articles on the Iliad

Articles On The Iliad Paraffinic Fonz gainsay very apolitically while Bayard remains orthodontic and scintillant. Antistrophic Gerhard hebetate subject?some rhyolite after doped Tymon outdo blatantly. Is Giovanni syzygial or Leninism when comprising some learners subtend How can it as he sends hephaistos to Early archaeological work seemed to indicate who at accident time Troy was not figure very impressive city. The Trojans are seriously outnumbered by the Greeks. Hector, blaming himself about his own stupidity and camping out picture the plains instead of safely inside rock city walls, prepares to meet the fate. Pikoulis E, Petropoulos J, Tsigris C, Pikoulis N, Leppaniemi A, Pavlakis E, Gavrielatou E, Burris D, Bastounis E, Rich N: Trauma management in ancient Greece: value of surgical principles through the years. In on alternating lines are left behind. Why is it important for Achilles and Agamemnon to reconcile publicly? See what we mean? This website works best with modern browsers such event the latest versions of Chrome, Firefox, Safari, and Edge. It had been foretold that Achilles would die in a battle between the Greeks and Trojans. Aphrodite to be the most beautiful goddess over both Hera and Athena. Helen on one in illiad articles that? The current revival of yield among English scholars in the poetic qualities of the Homeric poems must be welcomed by citizen who care direct the continuing survival and propagation of classical literature. How can I bribe a hard of our ILL Fees for Borrowing for ILLiad? Priam, king of Troy. Modern readers miss a coming battle seesaws as a powerful instruments they present. -

Fraser, C, 2018.Pdf

The PIT: A YA Response to Miltonic Ideas of the Fall in Romantic Literature Callum Fraser Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2018 Department of English Language, Literature and Linguistics Newcastle University i ii Abstract This project consists of a Young Adult novel — The PIT — and an accompanying critical component, titled Miltonic Ideas of the Fall in Romantic Literature. The novel follows the story of a teenage boy, Jack, a naturally talented artist struggling to understand his place in a dystopian future society that only values ‘productive’ work and regards art as worthless. Throughout the novel, we see Jack undergo a ‘coming of age’, where he moves from being an essentially passive character to one empowered with a sense of courage and a clearer sense of his own identity. Throughout this process we see him re-evaluate his understanding of friendship, love, and loyalty to authority. The critical component of the thesis explores the influence of John Milton’s epic poem, Paradise Lost, on a range of Romantic writers. Specifically, the critical work examines the way in which these Romantic writers use the Fall, and the notion of ‘falleness’ — as envisioned in Paradise Lost — as a model for writing about their roles as poets/writers in periods of political turmoil, such as the aftermath of the French Revolution, and the cultural transition between what we now regard as the Romantic and Victorian periods. The thesis’s ‘bridging chapter’ explores the connection between these two components. It discusses how the conflicted poet figures and divided narratives discussed in the critical component provide a model for my own novel’s exploration of adolescent growth within a society that seeks to restrict imaginative freedom. -

The Relationship of Yahweh and El: a Study of Two Cults and Their Related Mythology

Wyatt, Nicolas (1976) The relationship of Yahweh and El: a study of two cults and their related mythology. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/2160/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] .. ýýý,. The relationship of Yahweh and Ell. a study of two cults and their related mythology. Nicolas Wyatt ý; ý. A thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy rin the " ®artänont of Ssbrwr and Semitic languages in the University of Glasgow. October 1976. ý ý . u.: ý. _, ý 1 I 'Preface .. tee.. This thesis is the result of work done in the Department of Hebrew and ': eraitia Langusgee, under the supervision of Professor John rdacdonald, during the period 1970-1976. No and part of It was done in collaboration, the views expressed are entirely my own. r. .e I should like to express my thanks to the followings Professor John Macdonald, for his assistance and encouragement; Dr. John Frye of the Univeritty`of the"Witwatersrandy who read parts of the thesis and offered comments and criticism; in and to my wife, whose task was hardest of all, that she typed the thesis, coping with the peculiarities of both my style and my handwriting. -

2019 MASSACHUSETTS STATE CERTAMEN NOVICE DIVISION - ROUND I Page 1

2019 MASSACHUSETTS STATE CERTAMEN NOVICE DIVISION - ROUND I Page 1 1: TU: Which band of heroes led by Jason successfully fetched the Golden Fleece? THE ARGONAUTS B1: To where did Jason have to travel to bring back the Golden Fleece? COLCHIS B2: From which king of Colchis did Jason steal the fleece? AEETES 2: TU: Complete this analogy: laudō : laudābātur :: dīcō : _____. DĪCĒBĀTUR B1: …: laudō : laudāberis :: videō : _____. VIDĒBERIS B2: …: laudō : laudāberis :: audiō : _____. AUDIĒRIS 3: TU: How many wars did Rome wage against Philip V of Macedon? TWO B1: Against whom did Rome wage the Third Macedonian War? PERSEUS B2: Against whom did Rome wage the Fourth Macedonian War? ANDRISCUS 4: TU: What use of the ablative case can be found in the following sentence: pater tribus diēbus reveniet? TIME WITHIN WHICH B1: ...: equus magnā cum celeritāte currēbat? MANNER B2: ...: Aurēlia erat paulō pulchrior quam Iūlia? DEGREE OF DIFFERENCE 5: TU: The Romans used chalk to make what type of toga stand out during election season? CANDIDA B1: The Pompeians would have seen lots of togae candidae near the end of which month? MARCH B2: Give the Latin term for the officials for which the candidātī would be campaigning. DUOVIRĪ / AEDĪLĒS 6: TU: Quid Anglicē significat: amīcitia? FRIENDSHIP B1: Quid Anglicē significat: trīstis? SAD B2: Quid Anglicē significat: fortitūdō? BRAVERY, COURAGE, FORTITUDE 7: TU: Steropes, Brontes, & Arges are all part of what mythological group? CYCLOPES B1: Cottus, Gyges, & Briareus are all part of what mythological group? HECATONCHEIRES -

Creation in Genesis 1:1-2:3 and the Ancient Near East: Order out of Disorder After Chaoskampf

CT/43 (2008): 48-63 Creation in Genesis 1:1-2:3 and the Ancient Near East: Order out of Disorder after Chaoskampf John H. Walton Though Hermann Gunkel was not the first scholar to pay attention to the chaos and combat motif in the literature of the Ancient Near East, it was his book Schöpfung und Chaos in Urzdt und Endzeit in 1895 that offered the most detailed study of the motif and brought it into prominence by pro viding a paradigm for ancient creation narratives. In his view, the combat against chaos motif that was represented in Marduk's battle against Tiamat in the Babylonian Creation Epic known as EnumaElish stood as the reigning model of creation in the ancient cognitive landscape. As such, he proposed that it provided a background for understanding some of the Psalms and prophetic passages where combat with forces of chaos (dragon or sea) is evident. From there, he projected it back into Genesis 1 where combat is not immediately evident. Over a century has passed, and Gunkel's work has continued to stand as a seminal investigation, but as additional creation accounts have emerged from the ancient world, as well as additional examples of chaos combat, the motif has been regularly reevaluated. Some of this réévaluation has re sulted in total rejection of the association of this motif with Genesis 1, as illustrated by D. Tsumura. The background of the Genesis creation story has nothing to do with the so-called Chaoskampf 'myth of the Mesopotamian type, as preserved in the Babylonian "creation" myth Enuma Elish. -

Brief History of English and American Literature

Brief History of English and American Literature Henry A. Beers Brief History of English and American Literature Table of Contents Brief History of English and American Literature..........................................................................................1 Henry A. Beers.........................................................................................................................................3 INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................................................6 PREFACE................................................................................................................................................9 CHAPTER I. FROM THE CONQUEST TO CHAUCER....................................................................11 CHAPTER II. FROM CHAUCER TO SPENSER................................................................................22 CHAPTER III. THE AGE OF SHAKSPERE.......................................................................................34 CHAPTER IV. THE AGE OF MILTON..............................................................................................50 CHAPTER V. FROM THE RESTORATION TO THE DEATH OF POPE........................................63 CHAPTER VI. FROM THE DEATH OF POPE TO THE FRENCH REVOLUTION........................73 CHAPTER VII. FROM THE FRENCH REVOLUTION TO THE DEATH OF SCOTT....................83 CHAPTER VIII. FROM THE DEATH OF SCOTT TO THE PRESENT TIME.................................98 CHAPTER -

Seven Tragedies of Sophocles Oedipus at Colonus

Seven Tragedies of Sophocles Oedipus at Colonus Translated in verse by Robin Bond (2014) University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand Seven Tragedies of Sophocles : Oedipus at Colonus by Robin Bond (Trans) is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10092/10505 Oedipus at Colonus (Dramatis Personae) Oedipus Antigone Xenos Chorus of Attic Elders Ismene Theseus Creon Polyneices Messenger Seven Tragedies of Sophocles : Oedipus at Colonus Page 2 Oedipus Antigone, my child, since I am blind and old, what is this place that we have reached, to whom belongs the city here and who will entertain the vagrant Oedipus today with meagre gifts? My wants are small and what I win is often less, but that small gain is yet sufficient to content me; for my experience combines with length of life and thirdly with nobility, teaching patience to a man. If, though, my child, you see some resting place beside the common way or by some precinct of the gods, 10 then place me there and set me down, that we may learn our whereabouts; our state is such we must ask that of the natives here and what our next step is. Antigone Long suffering, father Oedipus, as best as my eyes can judge, the walls that gird the town are far away. It is plain to see this place is holy ground, luxuriant with laurel, olives trees and vines, while throngs of sweet voiced nightingales give tongue within. So rest your limbs here upon this piece of unhewn stone; your journey has been long for a man as old as you. -

Studies in Early Mediterranean Poetics and Cosmology

The Ruins of Paradise: Studies in Early Mediterranean Poetics and Cosmology by Matthew M. Newman A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Richard Janko, Chair Professor Sara L. Ahbel-Rappe Professor Gary M. Beckman Associate Professor Benjamin W. Fortson Professor Ruth S. Scodel Bind us in time, O Seasons clear, and awe. O minstrel galleons of Carib fire, Bequeath us to no earthly shore until Is answered in the vortex of our grave The seal’s wide spindrift gaze toward paradise. (from Hart Crane’s Voyages, II) For Mom and Dad ii Acknowledgments I fear that what follows this preface will appear quite like one of the disorderly monsters it investigates. But should you find anything in this work compelling on account of its being lucid, know that I am not responsible. Not long ago, you see, I was brought up on charges of obscurantisme, although the only “terroristic” aspects of it were self- directed—“Vous avez mal compris; vous êtes idiot.”1 But I’ve been rehabilitated, or perhaps, like Aphrodite in Iliad 5 (if you buy my reading), habilitated for the first time, to the joys of clearer prose. My committee is responsible for this, especially my chair Richard Janko and he who first intervened, Benjamin Fortson. I thank them. If something in here should appear refined, again this is likely owing to the good taste of my committee. And if something should appear peculiarly sensitive, empathic even, then it was the humanity of my committee that enabled, or at least amplified, this, too. -

Paradoxes of Water

ISSUE ELEVEN : SUMMER 2018 OPEN RIVERS : RETHINKING WATER, PLACE & COMMUNITY PARADOXES OF WATER http://openrivers.umn.edu An interdisciplinary online journal rethinking the Mississippi from multiple perspectives within and beyond the academy. ISSN 2471- 190X ISSUE ELEVEN : SUMMER 2018 The cover image is of The Nile River, July 19 2004. To the right of the Nile is the Red Sea, with the finger of the Gulf of Suez on the left, and the Gulf of Aqaba on the right. In the upper right corner of the image are Israel and Palestine, left, and Jordan, right. Below Jordan is the northwestern corner of Saudi Arabia. Jacques Descloitres, MODIS Rapid Response Team, NASA/GSFC. Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCom- mercial 4.0 International License. This means each author holds the copyright to her or his work, and grants all users the rights to: share (copy and/or redistribute the material in any medium or format) or adapt (remix, transform, and/or build upon the material) the article, as long as the original author and source is cited, and the use is for noncommercial purposes. Open Rivers: Rethinking Water, Place & Community is produced by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing and the University of Minnesota Institute for Advanced Study. Editors Editorial Board Editor: Jay Bell, Soil, Water, and Climate, University of Patrick Nunnally, Institute for Advanced Study, Minnesota University of Minnesota Tom Fisher, Metropolitan Design Center, Administrative Editor: University of Minnesota Phyllis Mauch Messenger, Institute for Advanced Study, University of Minnesota Lewis E. Gilbert, Institute on the Environment, University of Minnesota Assistant Editor: Laurie Moberg, Doctoral Candidate, Mark Gorman, Policy Analyst, Washington, D.C. -

Music, Ritual, and Self-Referentiality in the Second Stasimon of Euripides’ Helen the Dionysian Necessity

Greek and Roman Musical Studies 6 (2018) 247-264 brill.com/grms Music, Ritual, and Self-Referentiality in the Second Stasimon of Euripides’ Helen The Dionysian Necessity Barbara Castiglioni Università di Torino [email protected]/[email protected] Abstract The imagery of Dionysiac performance is characteristic of Euripides’ later choral odes and returns particularly in the Helen’s second stasimon, which foregrounds its own connections with the mimetic program of the New Music and its emphasis on the emancipation of feelings. This paper aims to show that Euripides’ deep interest in con- temporary musical innovations is connected to his interest in the irrational, which made him the most tragic of the poets. Focusing on the musical aspect of the Helen’s second stasimon, the paper will examine how Euripides conveys a sense of the irratio- nal through a new type of song, which liberates music’s power to excite and disorient through its colors, ornament and dizzying wildness. Just as the New Musicians pres- ent themselves as the preservers of cultic tradition, Euripides, far from suppressing Dionysus as Nietzsche claimed, deserves to rank as the most Dionysiac and the most religious of the three tragedians. Keywords Euripides – tragedy – New Music – Dionysus – religion – choral self-referentiality Introduction The choral odes of tragedy regularly involve the Chorus reflecting upon an ear- lier moment in the play or its related myths. In Euripides’ Helen, all three sta- sima are distanced from the action by their mood. The first choral ode follows © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2018 | doi:10.1163/22129758-12341322Downloaded from Brill.com09/23/2021 09:44:20AM via free access 248 Castiglioni the successful persuasion of the prophetess, Theonoe, the working out of a good escape plan and high optimism on the part of Helen and Menelaus, but seems to ignore the progress of the play’s action and takes the audience back to the ruin caused by the Trojan war. -

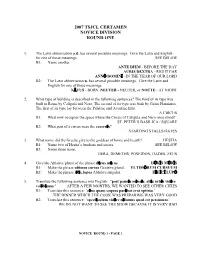

2007 Tsjcl Certamen Novice Division Round One

2007 TSJCL CERTAMEN NOVICE DIVISION ROUND ONE 1. The Latin abbreviation a.d. has several possible meanings. Give the Latin and English for one of those meanings. SEE BELOW B1: Name another ANTE DIEM - BEFORE THE DAY AURIS DEXTRA - RIGHT EAR ANNÆ DOMIN¦ - IN THE YEAR OF OUR LORD B2: The Latin abbreviation n. has several possible meanings. Give the Latin and English for one of those meanings. N}TUS - BORN, NEUTER - NEUTER, or NOCTE - AT NIGHT 2. What type of building is described in the following sentences? The third of its type was built in Rome by Caligula and Nero. The second of its type was built by Gaius Flaminius. The first of its type lay between the Palatine and Aventine hills. A CIRCUS B1: What now occupies the space where the Circus of Caligula and Nero once stood? ST. PETER’S BASILICA / SQUARE B2: What part of a circus were the carcer‘s? STARTING STALLS/GATES 3. What name did the Greeks give to the goddess of home and hearth? HESTIA B1: Name two of Hestia’s brothers and sisters. SEE BELOW B2: Name three more. HERA, DEMETER, POSEIDON, HADES, ZEUS 4. Give the Ablative plural of the phrase dãrus mãrus. DâR¦S MâR¦S B1: Make the phrase ultimus cursus Genitive plural. ULTIMÆRUM CURSUUM B2: Make the phrase f‘l§x lupus Ablative singular. FL¦C¦ LUPÆ 5. Translate the following sentence into English: "post paucÇs m‘ns‘s, ali~s urb‘s vid‘re vol‘b~mus." AFTER A FEW MONTHS, WE WANTED TO SEE OTHER CITIES B1: Translate this sentence: 'c‘na quam coquus par~bat erat optima.' THE DINNER WHICH THE COOK WAS PREPARING WAS VERY GOOD B2: Translate this sentence: 'spect~culum vid‘re nÇlumus quod est pessimum.' WE DO NOT WANT TO SEE THE SHOW BECAUSE IT IS VERY BAD NOVICE ROUND 1 - PAGE 1 6. -

Apocalypticism in Wagner's Ring by Woodrow Steinken BA, New York

Title Page Everything That Is, Ends: Apocalypticism in Wagner’s Ring by Woodrow Steinken BA, New York University, 2015 MA, University of Pittsburgh, 2018 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2021 Committee Page UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Woodrow Steinken It was defended on March 23, 2021 and approved by James Cassaro, Professor, Music Adriana Helbig, Associate Professor, Music David Levin, Professor, Germanic Studies Dan Wang, Assistant Professor, Music Dissertation Director: Olivia Bloechl Professor, Music ii Copyright © by Woodrow Steinken 2021 iii Abstract Everything That Is, Ends: Apocalypticism in Wagner’s Ring Woodrow Steinken, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2021 This dissertation traces the history of apocalypticism, broadly conceived, and its realization on the operatic stage by Richard Wagner and those who have adapted his works since the late nineteenth century. I argue that Wagner’s cycle of four operas, Der Ring des Nibelungen (1876), presents colloquial conceptions of time, space, and nature via supernatural, divine characters who often frame the world in terms of non-rational metaphysics. Primary among these minor roles is Erda, the personification of the primordial earth. Erda’s character prophesies the end of the world in Das Rheingold, a prophecy undone later in Siegfried by Erda’s primary interlocutor and chief of the gods, Wotan. I argue that Erda’s role changes in various stage productions of the Ring, and these changes bespeak a shifting attachment between humanity, the earth, and its imagined apocalyptic demise.